Structural Hydrology and Limiting Summer Conditions of San Juan County Fish-Bearing Streams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SONW Maintext

STATE of the NORTHWEST Revised 2000 Edition O THER N ORTHWEST E NVIRONMENT WATCH T ITLES Seven Wonders: Everyday Things for a Healthier Planet Green-Collar Jobs Tax Shift Over Our Heads: A Local Look at Global Climate Misplaced Blame: The Real Roots of Population Growth Stuff: The Secret Lives of Everyday Things The Car and the City This Place on Earth: Home and the Practice of Permanence Hazardous Handouts: Taxpayer Subsidies to Environmental Degradation State of the Northwest STATE of the NORTHWEST Revised 2000 Edition John C. Ryan RESEARCH ASSISTANCE BY Aaron Best Jocelyn Garovoy Joanna Lemly Amy Mayfield Meg O’Leary Aaron Tinker Paige Wilder NEW REPORT 9 N ORTHWEST E NVIRONMENT W ATCH ◆ S EATTLE N ORTHWEST E NVIRONMENT WATCH IS AN INDEPENDENT, not-for-profit research center in Seattle, Washington, with an affiliated charitable organization, NEW BC, in Victoria, British Columbia. Their joint mission: to foster a sustainable economy and way of life through- out the Pacific Northwest—the biological region stretching from south- ern Alaska to northern California and from the Pacific Ocean to the crest of the Rockies. Northwest Environment Watch is founded on the belief that if northwesterners cannot create an environmentally sound economy in their home place—the greenest corner of history’s richest civilization—then it probably cannot be done. If they can, they will set an example for the world. Copyright © 2000 Northwest Environment Watch Excerpts from this book may be printed in periodicals with written permission from Northwest Environment Watch. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 99-069862 ISBN 1-886093-10-5 Design: Cathy Schwartz Cover photo: Natalie Fobes, from Reaching Home: Pacific Salmon, Pacific People (Seattle: Alaska Northwest Books, 1994) Editing and composition: Ellen W. -

Design and Methods of the Pacific Northwest Stream Quality Assessment (PNSQA), 2015

National Water-Quality Assessment Project Design and Methods of the Pacific Northwest Stream Quality Assessment (PNSQA), 2015 Open-File Report 2017–1103 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Background: Photograph showing U.S. Geological Survey Hydrologic Technician collecting an equal-width-increment (EWI) water sample on the South Fork Newaukum River, Washington. Photograph by R.W. Sheibley, U.S. Geological Survey, June 2015. Top inset: Photograph showing U.S. Geological Survey Ecologist scraping a rock using a circular template for the analysis of Algal biomass and community composition, June 2015. Photograph by U.S. Geological Survey. Bottom inset: Photograph showing juvenile coho salmon being measured during a fish survey for the Pacific Northwest Stream Quality Assessment, June 2015. Photograph by Peter van Metre, U.S. Geological Survey. Design and Methods of the Pacific Northwest Stream Quality Assessment (PNSQA), 2015 By Richard W. Sheibley, Jennifer L. Morace, Celeste A. Journey, Peter C. Van Metre, Amanda H. Bell, Naomi Nakagaki, Daniel T. Button, and Sharon L. Qi National Water-Quality Assessment Project Open-File Report 2017–1103 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information pr oducts, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https:/store.usgs.gov. -

Fish Ecology in Tropical Streams

Author's personal copy 5 Fish Ecology in Tropical Streams Kirk O. Winemiller, Angelo A. Agostinho, and Érica Pellegrini Caramaschi I. Introduction 107 II. Stream Habitats and Fish Faunas in the Tropics 109 III. Reproductive Strategies and Population Dynamics 124 IV. Feeding Strategies and Food-Web Structure 129 V. Conservation of Fish Biodiversity 136 VI. Management to Alleviate Human Impacts and Restore Degraded Streams 139 VII. Research Needs 139 References 140 This chapter emphasizes the ecological responses of fishes to spatial and temporal variation in tropical stream habitats. At the global scale, the Neotropics has the highest fish fauna richness, with estimates ranging as high as 8000 species. Larger drainage basins tend to be associated with greater local and regional species richness. Within longitudinal stream gradients, the number of species increases with declining elevation. Tropical stream fishes encompass highly diverse repro- ductive strategies ranging from egg scattering to mouth brooding and livebearing, with reproductive seasons ranging from a few days to the entire year. Relationships between life-history strategies and population dynamics in different environmental settings are reviewed briefly. Fishes in tropical streams exhibit diverse feeding behaviors, including specialized niches, such as fin and scale feeding, not normally observed in temperate stream fishes. Many tropical stream fishes have greater diet breadth while exploiting abundant resources during the wet season, and lower diet breadth during the dry season as a consequence of specialized feeding on a subset of resources. Niche complementarity with high overlap in habitat use is usually accompanied by low dietary overlap. Ecological specializations and strong associations between form and function in tropical stream fishes provide clear examples of evolutionary convergence. -

Evaluating the Effects of Vortex Rock Weir Stability on Physical Complexity Penitencia and Wildcat Creeks

Evaluating the Effects of Vortex Rock Weir Stability on Physical Complexity Penitencia and Wildcat Creeks Emily Corwin Katie Jagt Leigh Neary Completed for LA 227 River Restoration Fall 2007 Evaluating the effects of vortex rock weir stability on physical complexity Page i Evaluating the Effects of Vortex Rock Weir Stability on Physical Complexity Penitencia and Wildcat Creeks Emily Corwin Katie Jagt Leigh Neary Department of Civil and Department of Civil and Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Environmental Engineering Environmental Engineering [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Site Descriptions…………………………………………………………………………………………....9 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………......11 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………………15 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………...18 References…………………………………………………………………………………………………19 Appendix A: Variance Calculation Methods……………………………………………………………...20 Appendix B: Additional Figures and Tables………………………………………………………………21 List of Figures Figure 1. General configuration of vortex rock weirs…………………………..………………...……... .5 Figure 2. The four degrees of structural integrity; rating criteria for vortex rock weirs………..………....7 Figure 3. The six degrees of bed and bank degradation; erosion rating criteria…………………………...7 Figure 4. The control channel model schematic. ………………………………………………………… -

Platypus Predation Has Differential Effects on Aquatic Invertebrates In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Platypus predation has diferential efects on aquatic invertebrates in contrasting stream and lake ecosystems Tanya A. McLachlan‑Troup1*, Stewart C. Nicol 2 & Christopher R. Dickman 1 Predators can have strong impacts on prey populations, with cascading efects on lower trophic levels. Although such efects are well known in aquatic ecosystems, few studies have explored the infuence of predatory aquatic mammals, or whether the same predator has similar efects in contrasting systems. We investigated the efects of platypus (Monotremata: Ornithorhynchus anatinus) on its benthic invertebrate prey, and tested predictions that this voracious forager would more strongly afect invertebrates—and indirectly, epilithic algae—in a mesotrophic lake than in a dynamic stream ecosystem. Hypotheses were tested using novel manipulative experiments involving platypus‑ exclusion cages. Platypuses had strongly suppressive efects on invertebrate prey populations, especially detritivores and omnivores, but weaker or inconsistent efects on invertebrate taxon richness and composition. Contrary to expectation, predation efects were stronger in the stream than the lake; no efects were found on algae in either ecosystem due to weak efects of platypuses on herbivorous invertebrates. Platypuses did not cause redistribution of sediment via their foraging activities. Platypuses can clearly have both strong and subtle efects on aquatic food webs that may vary widely between ecosystems and locations, but further research is needed to replicate our experiments and understand the contextual drivers of this variation. Predation can strongly influence the size and dynamics of prey populations and the structure of prey communities1–3. Such infuences can arise if predators selectively depredate prey species from the array of prey taxa that is available (consumptive efects,e.g. -

Table of Contents Executive Summary

Flint Hills wetlands and aquatic vertebrate responses to climate change. Thomas M. Luhring, Ph.D. Department of Biological Sciences, Wichita State University, 1845 Fairmount Street, Wichita, KS 67260. Phone: (316) 978-6046 Email: [email protected] Data collected and prepared by the following students and staff at Wichita State University (alphabetical order): Stephanie Bristow, Shania Burkhead, Phi Hoang, Dexter Mardis, Justin Oettle, Annie Pham, Sarah Pulliam, Christine Streid, Emily Stybr, Krista Ward, Jake Wright Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Rapid Wetland Inventory & Preliminary Hydroperiod Indices ..................................................................... 4 Field-Corrected Wetland Hydroperiods/Wetland Fill & Dry Rates ............................................................... 6 Aquatic Vertebrate Inventories: Aquatic Surveys ......................................................................................... 7 Aquatic Vertebrate Inventories: Aural Surveys .......................................................................................... 10 Synthesis ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Appendix I: Jake Wright Master’s Thesis (Early Draft Provided to KDWPT) ............................................... 14 Appendix II: Krista Ward Master’s -

Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana Luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: a Survey of Historical Localities, 2009

Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon/Washington U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Region 6 U.S. Forest Service Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: A Survey of Historical Localities, 2009 By Christopher A. Pearl, Stephanie K. Galvan, Michael J. Adams, and Brome McCreary Open-File Report 2010–1235 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photographs of Oregon spotted frog and pond survey site. Photographs by the U.S. Geological Survey. Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: A Survey of Historical Localities, 2009 By Christopher A. Pearl, Stephanie K. Galvan, Michael J. Adams, and Brome McCreary Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon/Washington U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Region 6 U.S. Forest Service Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) Open-File Report 2010-1235 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod. To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Suggested citation: Pearl, C.A., Galvan, S.K., Adams, M.J., and McCreary, B., 2010, Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris) in southeastern Oregon: A survey of historical localities, 2009: U.S. -

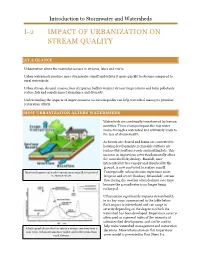

Introduction to Stormwater and Watersheds I-2 IMPACT of URBANIZATION on STREAM QUALITY

Introduction to Stormwater and Watersheds I-2 IMPACT OF URBANIZATION ON STREAM QUALITY AT A GLANCE Urbanization alters the natural processes in streams, lakes and rivers. Urban watersheds produce more stormwater runoff and deliver it more quickly to streams compared to rural watersheds. Urban stream channel erosion, loss of riparian buffers warmer stream temperatures and toxic pollutants reduce fish and aquatic insect abundance and diversity. Understanding the impacts of imperviousness on stream quality can help watershed managers prioritize restoration efforts. HOW URBANIZATION ALTERS WATERSHEDS Watersheds are continually transformed by human activities. These changes impact the way water moves through a watershed and ultimately leads to the loss of stream health. As forests are cleared and farms are converted to housing developments, permeable surfaces are replaced by rooftops, roads and parking lots. This increase in impervious cover fundamentally alters the watershed’s hydrology. Rainfall, once intercepted by tree canopy and absorbed by the ground, is now converted to surface runoff. Increased impervious surface means more rainfall is converted Consequently, urban streams experience more to surface runoff. frequent and severe flooding. Meanwhile, stream flow during dry weather often declines over time because the groundwater is no longer being recharged. Urbanization significantly impacts stream health in six key ways, summarized in the table below. Each impact is interrelated and can range in severity depending on the degree to which the watershed has been developed. Impervious cover is often used as a general index of the intensity of subwatershed development, and can be used to help make watershed management and restoration A hydrograph shows the flow rate in a stream over time after a rain event. -

Pool Application

City of Danbury For Questions Please Contact the Permit Office at (203) 796-1653 155 Deer Hill Ave Danbury, CT 06810 Application # POOL APPLICATION Use the following Table for departmental areas of the Application that need to be completed for your specific project. *********Required Responsible Departments******** Type of Project Health Septic / Well Engineering Zoning Building Above or In-Ground Pool * * Yes Yes * One or the other or combination using sewer and water (Engineering) septic or well (Health) Table to be used as a guide only. Department can require permit at their discretion. Certain permits will require different types of maps and drawings to accompany their submission. The following is a list of Plan requirements by Permits. Type of Project Septic Engineering Zoning Building Above or In- Sub-Surface Check back-flow A-2 Survey showing existing 2 Copies of Ground Pool Disposal Plan prevention structures and Proposed Pool Building Plans In order for a Certificate of Occupancy to be issued the following must be completed. Type of Project Septic Zoning Building Above or In-Ground Pool Health Dept. Approval Inspection prior to final All required inspection building inspection completed Handouts are available at our Web Site (www.ci.danbury.ct.us) and from counter staff. These drawings are meant to assist you in completing drawings. They are to be used as guides only. Assessors lot #: Town Clerk Map #: Town Clerk Lot #: Property Address: Application Date: Current Use of Property: Zone Code: Total Estimated Construction Cost: Work Description: (Size and location): Please list the following information for all Professionals and Contractors: NAME, LICENSE NO., COMPANY, TELEPHONE, FAX, E-MAIL. -

49 Inspirational Travel Secrets from the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today

2010 49 Inspirational Travel Secrets From the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today www.tripbase.com Front Cover Main Index Foreword Congratulations on downloading your Best Kept Travel Secrets eBook. You're now part of a unique collaborative charity project, the first of its kind to take place on the Internet! The Best Kept Travel Secrets project was initiated with just one blog post back in November 2009. Since then, over 200 of the most talented travel bloggers and writers across the globe have contributed more than 500 inspirational travel secrets. These phenomenal travel gems have now been compiled into a series of travel eBooks. Awe-inspiring places, insider info and expert tips... you'll find 49 amazing travel secrets within this eBook. The best part about this is that you've helped contribute to a great cause. About Tripbase Founded in May 2007, Tripbase pioneered the Internet's first "destination discovery engine". Tripbase saves you from the time-consuming and frustrating online travel search by matching you up with your ideal vacation destination. Tripbase was named Top Travel Website for Destination Ideas by Travel and Leisure magazine in November 2008. www.tripbase.com Copyright / Terms of Use: US eBook - 49 secrets - Release 1.02 (May 24th, 2010) | Use of this ebook subject to these terms and conditions. Tripbase Travel Secrets E-books are free to be shared and distributed according to this creative commons copyright . All text and images within the e-books, however, are subject to the copyright of their respective owners. Best Kept Travel Secrets 2010 Tripbase.com 2 Front Cover Main Index These Secrets Make Dirty Water Clean Right now, almost one billion people in the world don't have access to clean drinking water. -

VILLAGE of Valley Stream PRESENT the 2018 SUMMER GUIDE

MAYOR FARE AND THE INCORPORATED VILLAGE OF Valley Stream PRESENT THE 2018 SUMMER GUIDE Valley Stream, New York . WHERE OUR RECREATIONAL PROGRAMS READ ABOUT OUR TALENTED VALLEY STREAM STUDENT ARTISTS INSIDE… ARE SECOND TO NONE ! A Message from Our Mayor Welcome to Summer Excitement Dear Neighbors, Summer is just around the corner, and with it another great season of recreational programs for Valley Stream children and adults to enjoy. Our dedicated parks and recreation staff are hard at work getting an extensive array of warm weather activities ready for Valley Streamers of all ages. We are always seeking to build upon what we already have in place, and this year is no exception. Children who frequent Barrett and Arlington Parks and the Kay Everson play area in Hendrickson Park will again enjoy the three beautiful new interactive playgrounds that were completed a few years ago. In addition to such popular regulars as Camp Barrett, mini-golf and, of course, our state-of-the-art pool complex, we will again play host to US Sports Institute’s sports camp for children and adults, expanded outdoor movie nights on the banks of beautiful Hendrickson Lake, and other surprises along the way. Back by popular demand will be our 6th Annual Family Fishing Weekend, so mark your calendars for June 23rd and 24th for this outstanding family-friendly activity. Mayor & Board of Trustees If you’ve been to the pool in recent summers you would have noticed the new large shade structure at the west end of the pool deck, where patrons can gather to escape the hot afternoon sun. -

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119Km (1,324Miles) from Home

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119km (1,324miles) from home Hi welcome back everyone… Many of you have confirmed your anticipation in our travel tales ahead. Should there be anyone NOT wishing to receive these, please let us know; we will amend our mailing list, no questions asked! Figuring, we passed our six-month ‘Cape Crusader test run’ run last year, we decided to embark on a twelve-month stint this year. Maybe longer – depends on how we’ll adjust to the nomadic ways of gypsies in the longer term; look/see what life on the road will throw at us So… all a bit open-ended but we’ve done it: Our home is stripped bare and rented. Anyone toying with similar thoughts - One must not underestimate the monumental effort it takes of breaking free from societal life’s seemingly countless entrapments! Whose crazy idea exactly was this in the first place?! Hello golfers, proudly managed a “(w)hole in one”: Squeezing our entire possessions into one room. Credit to Katherine’s most skilful planning and removalists’ even more astonishing stacking skills. This is our vision Empty lounge room camping: Family farewell with sisters Jennifer, Charmaine and Brian FLASHBACK to April 3: In the meantime up north, the wet season has ended, the oppressive humidity disappeared and the welcome heat of the ‘dry’ has arrived beyond the Tropic Of Capricorn: The siren call of tropical Northern Australia beckons yet again. The dry season normally lasts for eight months: No rain, the bluest of blue skies and balmy nights.