The Midnight Express (1978) Phenomenon and the Image of Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Service of Others: from Rose Hill to Lincoln Center

Fordham Law Review Volume 82 Issue 4 Article 1 2014 In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 1533 (2014). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol82/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEDICATION IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS: FROM ROSE HILL TO LINCOLN CENTER Constantine N. Katsoris* At the start of the 2014 to 2015 academic year, Fordham University School of Law will begin classes at a brand new, state-of-the-art building located adjacent to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. This new building will be the eighth location for Fordham Law School in New York City. From its start at Rose Hill in the Bronx, New York, to its various locations in downtown Manhattan, and finally, to its two locations at Lincoln Center, the law school’s education and values have remained constant: legal excellence through public service. This Article examines the law school’s rich history in public service through the lives and work of its storied deans, demonstrating how each has lived up to the law school’s motto In the service of others and concludes with a look into Fordham Law School’s future. -

Sir Alan Parker Donates Working Archives to Bfi

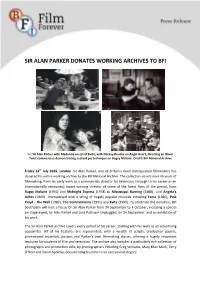

SIR ALAN PARKER DONATES WORKING ARCHIVES TO BFI l-r: Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on set of Evita; with Mickey Rourke on Angel Heart; directing an Oliver Twist commercial; demonstrating custard pie technique on Bugsy Malone. Credit: BFI National Archive Friday 24th July 2015, London. Sir Alan Parker, one of Britain’s most distinguished filmmakers has donated his entire working archive to the BFI National Archive. The collection covers over 45 years of filmmaking, from his early work as a commercials director for television, through to his career as an internationally renowned, award-winning director of some of the finest films of the period, from Bugsy Malone (1976) and Midnight Express (1978) to Mississippi Burning (1988) and Angela’s Ashes (1999) interspersed with a string of hugely popular musicals including Fame (1980), Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982), The Commitments (1991) and Evita (1996). To celebrate the donation, BFI Southbank will host a Focus On Sir Alan Parker from 24 September to 4 October, including a special on stage event, Sir Alan Parker and Lord Puttnam Unplugged, on 24 September, and an exhibition of his work. The Sir Alan Parker archive covers every period of his career, starting with his work as an advertising copywriter. All of his features are represented, with a wealth of scripts, production papers, promotional materials, posters and Parker’s own filmmaking diaries, offering a hugely important resource for students of film and television. The archive also includes a particularly rich collection of photographs and production stills, by photographers including Greg Williams, Mary Ellen Mark, Terry O'Neill and David Appleby, documenting his films to an exceptional degree. -

THE MYTH of 'TERRIBLE TURK' and 'LUSTFUL TURK' Nevs

THE WESTERN IMAGE OF TURKS FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE 21ST CENTURY: THE MYTH OF ‘TERRIBLE TURK’ AND ‘LUSTFUL TURK’ Nevsal Olcen Tiryakioglu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. i Abstract The Western image of Turks is identified with two distinctive stereotypes: ‘Terrible Turk’ and ‘Lustful Turk.’ These stereotypical images are deeply rooted in the history of the Ottoman Empire and its encounters with Christian Europe. Because of their fear of being dominated by Islam, European Christians defined the Turks as the wicked ‘Other’ against their perfect ‘Self.’ Since the beginning of Crusades, the Western image of Turks is associated with cruelty, barbarity, murderousness, immorality, and sexual perversion. These characteristics still appear in cinematic representations of Turks. In Western films such as Lawrence of Arabia and Midnight Express, the portrayals of Turks echo the stereotypes of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ This thesis argues that these stereotypes have transformed into a myth and continued to exist uniformly in Western contemporary cinema. The thesis attempts to ascertain the uniformity and consistency of the cinematic image of Turks and determine the associations between this image and the myths of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ To achieve this goal, this thesis examines the trajectory of the Turkish image in Western discourse between the 11th and 21st centuries. -

Open PDF 120KB

Written evidence submitted by Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA The Digital Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee Inquiry into the Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sector 1 What has been the immediate impact of Covid-19 on the sector? Devastating: especially in relation to the live creative arts, festivals, theatres, classical music etc. To quote the motto of the English monarch Edward III, ‘it is as it is’ but the sight of theatres going into administration eg the Leicester Haymarket and the Southampton Nuffield is a harbinger of worse to come. Who knows what will happen to venues and concert halls such as the Usher Hall in Edinburgh? If there is one area in which the UK can truly be said to have punched above it’s weight and established and maintained world class excellence, both critically and commercially, it is in the creative industries. This internationally recognised success –economic, cultural and artistic is now at severe risk. HMG has invested, (who knows how much?) in maintaining employment in the car industry in the North East of England so that Nissan can stay there. The creative industries deserve no less, indeed much more and investment now will secure many more jobs across the UK with wider benefits well beyond the economic. Taking the long view will produce future income in taxation from the many other businesses which benefit from having such a vibrant sector: hotels, restaurants, transport etc. Edinburgh hosts the largest are festival in the world, by some margin and it will not take place in 2020. The analysis provided by the Creative Industries Federation indicates the scale of current crisis. -

Not Showing at This Cinema

greenlit just before he died, was an adaptation of A PIN TO SEE THE NIGHT Walter Hamilton’s 1968 novel All the Little Animals, exploring the friendship between a boy and an THE PEEPSHOW CREATURES old man who patrols roads at night collecting the Dir: Robert Hamer 1949 Dir: Val Guest 1957 roadkill. Reeves prepared a treatment, locations Adaptation of a 1934 novel by F. Tennyson Jesse Robert Neville is the last man on earth after a were scouted and Arthur Lowe was to play the about a young woman wrongly convicted as an mysterious plague has turned the rest of the lead. Thirty years later the book was adapted for accomplice when her lover murders her husband; a population into vampires who swarm around his the screen and directed by Jeremy Thomas starring thinly fictionalised account of Edith Thompson and house every night, hungering for his blood. By day, John Hurt and Christian Bale. the Ilford Murder case of 1922. With Margaret he hunts out the vampires’ lairs and kills them Lockwood in the lead, this was something of a with stakes through the heart, while obsessively dream project that Robert Hamer tried to get off searching for an antidote and trying to work out the ground at Ealing. Despite a dazzling CV that the cause of his immunity. Richard Matheson wrote ISHTAR includes the masterpiece Kind Hearts and Coronets the screenplay for The Night Creatures for Hammer Dir: Donald Cammell 1971-73 (1949), Hamer was unable to persuade studio Films in 1957 based on his own hugely influential The co-director of Performance (1970), Cammell boss Michael Balcon to back the project. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION This study guide attempts to trace the production process o1 the forthcoming film War of the Buttons' from its Conception to its release in the cinema. In tracing this route students are asked to carry out a number of tasks, many of which relate directly to decisions which have to be made during film production. Following the development of this one film we have tried to draw conclusions about the mainstream film making process. However, it is important to bear one thing in mind. As the production accountant for 'War of the Buttons', John Trehy points out: "Each and every feature film I've worked on is completely different from every other, and can only be looked on a as prototype. The production process is always difficult when you're dealing with prototypes and this often explains why so many films exceed their original budgets. 'How can you be a million or two dollars over?' - is a question that is often asked. The reason is that certain kinds of films are unique and the production team must do things that have never been done before." Thus, whilst many of the processes which are dealt with in this guide could well hold good for other films, there are certain aspects which are unique. The guide examines both areas and encourages students to use their own experience of film viewing and cinema-going to explore both the generalities and the uniqueness. There is no attempt to show 'the wonderful world of filmmaking'; rather the guide reveals an industrial process, one in which the time spent on preparing for the film to be shot far outweighs the amount of time actually spent shooting. -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9m52q2hk Author Wight, David M. Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERISITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by David M. Wight Dissertation Committee: Professor Emily S. Rosenberg, chair Professor Mark LeVine Associate Professor Salim Yaqub 2014 © 2014 David M. Wight DEDICATION To Michelle ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Road to the Oil Shock 14 CHAPTER 2: Structuring Petrodollar Flows 78 CHAPTER 3: Visions of Petrodollar Promise and Peril 127 CHAPTER 4: The Triangle to the Nile 189 CHAPTER 5: The Carter Administration and the Petrodollar-Arms Complex 231 CONCLUSION 277 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Sectors of the MENA as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 19 Figure 1.2 Selected Countries as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 20 Figure 1.3 Current Account Balances of the Non-Communist World, 1970-1977 22 Figure 1.4 Value of US Exports to the MENA, 1946-1977 24 Figure 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 255 iv LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Net Change in Deployment of OPEC’s Capital Surplus, 1974-1976 120 Table 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 256 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a cliché that one accumulates countless debts while writing a monograph, but in researching and writing this dissertation I have come to learn the depth of the truth of this statement. -

TITLE New Teachers Packet. INSTITUTION Journalism Education Association

DOCUMENT RESUME A ED 451 550 CS 510 TITLE New Teachers Packet. INSTITUTION Journalism Education Association. PUB DATE 1998-04-00 NOTE 217p.; Prepared by the Journalism Education Curriculum/Development Committee, Jan Hensel, Chair. Contributors include: Candace Perkins Bowen, Michele Dunaway, Mary Lu Foreman, Connie Fulkerson, Pat Graff, Jan Hensel, RobMelton, Scoobie Ryan, and Valerie Thompson. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Guides; Newspapers; Photojournalism; Production Techniques; Professional Associations; *Scholastic Journalism; School Publications; Secondary Education; Student Publications; Worksheets; Yearbooks ABSTRACT This packet of information for new scholastic journalism teachers (or advisers) compiles information on professional associations in journalism education, offers curriculum guides and general help, and contains worksheets and handouts. Sections of the packet are:(1) Professional Help (Journalism Education Association Information, and Other Scholastic Press Associations);(2) Curriculum Guides (Beginning Journalism, Electronic Publishing, Newspaper Production, and Yearbook Production);(3) General Helps (General Tips, Sample Publications Guidelines, Sample Ad Contract, and Sample Style Book); and (4) Worksheets and Handouts (materials cover General Journalism, Middle/Junior High, Newspaper, Photography, and Yearbook). (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Journalism Education Association ma- Teackers -

The Bookwallah Six Writers, a Nomadic Library, 2000Km by Train

The Bookwallah Six writers, a nomadic library, 2000km by train. Chandrahas Choudhury Michelle de Kretser Benjamin Law Kirsty Murray Sudeep Sen Annie Zaidi Mumbai October 31–November 4 Goa November 5–7 Bangalore November 8–13 Chennai November 14–16 Pondicherry November 17–21 1 2 Contents. Map 2 Overview 3 .... The writers 4 — Chandrahas Choudhury 4 — Michelle de Kretser 4 — Benjamin Law 5 — Kirsty Murray 6 — Sudeep Sen 6 — Annie Zaidi 7 .... The Bookwallah Nomadic Library 8 — The cases 8 — The books 8 — The designers 9 .... Mumbai 12 Goa 14 Bangalore 16 Chennai 18 Pondicherry 20 .... The library catalogue 22 .... The bookwallahs 46 The supporters 47 The publishers 48 1 Map. MUMBAI goA bangAlore chennai pondIcherry 2 Overview. The Bookwallah takes six writers and an ingenious lian books. Bound in kangaroo leather, the cases travelling library across south India by train. In- house fiction, non-fiction, poetry and children’s dian writers Chandrahas Choudhury, Annie Zaidi books. They’re part library, part art installation; and Sudeep Sen join Australian writers Michelle De visitors can browse, sit and read, or take part in Kretser, Benjamin Law and Kirsty Murray on a jour- intimate library events. If you see a book you like, ney through the cities and towns of modern India. you can borrow it from your local library: copies of They will share books and ideas, meet readers, and the books will be donated to a local library in each seek out stories, conversations and connections destination along the way. along the way. As well as public events, the Bookwallah tour In Mumbai you’ll find us at the Literature Live! includes private encounters with local writers, Mumbai LitFest, before we head to Goa for a Book- artists and thinkers in each city, designed to illu- wallah mini-festival at the Literati Bookshop. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Age 46

ISSUE 72 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER AFI.com/Silver JULY 2–SEPTEMBER 16, 2015 ‘90s Cinema Now Best of the ‘80s Ingrid Bergman Centennial Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York Tell It Like It Is: Contents Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 ........................2 July 4–September 5 Keepin’ It Real: ‘90s Cinema Now ............4 In early 1968, William Greaves began shooting in Central Park, and the resulting film, SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM: TAKE ONE, came to be considered one of the major works of American independent cinema. Later that year, following Ingrid Bergman Centennial .......................9 a staff strike, WNET’s newly created program BLACK JOURNAL (with Greaves as executive producer) was established “under black editorial control,” becoming the first nationally syndicated newsmagazine of its kind, and home base for a Best of Totally Awesome: new generation of filmmakers redefining documentary. 1968 also marked the production of the first Hollywood studio film Great Films of the 1980s .....................13 directed by an African American, Gordon Park’s THE LEARNING TREE. Shortly thereafter, actor/playwright/screenwriter/ novelist Bill Gunn directed the studio-backed STOP, which remains unreleased by Warner Bros. to this day. Gunn, rejected Bugs Bunny 75th Anniversary ...............14 by the industry that had courted him, then directed the independent classic GANJA AND HESS, ushering in a new type of horror film — which Ishmael Reed called “what might be the country’s most intellectual and sophisticated horror films.” Calendar ............................................15 This survey is comprised of key films produced between 1968 and 1986, when Spike Lee’s first feature, the independently Special Engagements ............12-14, 16 produced SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT, was released theatrically — and followed by a new era of studio filmmaking by black directors. -

Preface 1 Olof Palme: “Moral Duty Is Discontent on a Large Scale”: Creation

Notes Preface 1. This list is not exhaustive: Benezir Bhutto, Daniel Ortega, and Fulgencio Battista are among others whose political careers were resurrected after falling from power. 1 Olof Palme: “Moral Duty Is Discontent on a Large Scale”: Creation 1. Hans Haste, Olof Palme (Paris: Descartes et Cie., 1994), 25. tr. of Haste, Boken om Olof Palme. Hans Liv, Hans Gärning, Hans Död (Stockholm: Tiden, 1986). Chris Mosey, Cruel Awakening: Sweden and the Killing of Olof Palme (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 80. 2. Olof Ruin, Tage Erlander: Serving the Welfare State, 1946–1949 (Pittsburgh: Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1990), 53–54. 3. Olof Palme, La Rendez- vous suedois. Conversations avec Serge Richard (Paris: Stock: 1976), 40. 4. Palme, Rendez- vous, 14, 29–30. 5. Christer Isaksson, Palme Privat. I skuggan av Erlander (Falun: Ekerlios Förlag, 1995), 146. Haste, 37. 6. Isaksson, 147–148. 7. Robert Dalsjö. Life- Line Lost. The Rise and Fall of ‘Neutral’ Sweden’s Secret Reserve Option of Wartime Help from the West. Stockholm: Santérus Academic Press, 2006), 23. Modification of Swedish neutrality policy started early in the Cold War. Washington began applying economic pres- sure (delays and even stoppages of exports), which together with political and strategic considerations prompted Swedish acknowledgment of “ideo- logical affirmation” in the West – although not participation in NATO, as the State Department had wished. Birgit Karlsson, “Neutrality and Economy: The Redefining of Swedish Neutrality, 1946–1952,” Journal of Peace Research 32: 1 (1995), 42, 46. 8. NSC 6006/1.Statens Offentliga Utredningar (hereafter, SOU – published reports by official commissions), discussed by Dalsjö. -

Live in HD Film Streams Supporters Film

Film Streams Programming Calendar The Ruth Sokolof Theater . April – June 2010 v3.4 The Times of Harvey Milk 1984 © New Yorker Films/Photofest Out in Film June 3 – July 1, 2010 Word Is Out 1977 Law of Desire 1987 The Wedding Banquet 1993 The Times of Harvey Milk 1984 Mala Noche 1985 Longtime Companion 1989 High Art 1998 Prodigal Sons First-Run Happy Together 1997 © Kino/Photofest When it was released in the late 1970s, the documentary WORD IS OUT: and Wong Kar Wai (HAPPY TOGETHER) to ground- STORIES OF SOME OF OUR LIVES created a shockwave by talking openly breaking dramas (LONGTIME COMPANION, HIGH about lesbian and gay identity in America—decades before Ang Lee’s BROKE- ART) to pivotal documentaries such as THE TIMES BACK MOUNTAIN and Gus Van Sant’s MILK brought similar narratives to OF HARVEY MILK (an inspiration for Dustin Lance mainstream multiplexes. Presented in conjunction with LGBT Pride Month Black’s 2008 Oscar-winning script for MILK), Kim- 2010, our Out in Film series features a variety of artistically innovative films berly Reed’s autobiographical new film PRODIGAL relating in different ways to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender experi- SONS, and a new UCLA restoration and Milestone ence—from early, important works by acclaimed directors Lee (THE WEDDING Films re-release of WORD IS OUT. BANQUET), Van Sant (MALA NOCHE), Pedro Almodóvar (LAW OF DESIRE), See reverse side of newsletter for full calendar of films and dates. Forever Young Family & Children’s Series Spring 2009 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 1968 James and A Town Called Panic First-Run the Giant Peach 1996 Mary Poppins 1964 Tahaan 2009 The Secret of Kells First-Run Bugsy Malone 1976 This spring our Forever Young series for all ages features half a century of great cinema, from Julie Andrews’ Oscar-winning screen debut as MARY POPPINS 46 years ago to the 2010 Academy Award Nominee for Best Animat- ed Feature THE SECRET OF KELLS.