Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): Taxonomy and Character Evolution

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): taxonomy and character evolution This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/74776 since 2016-10-06T16:59:44Z Published version: DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 23 September 2021 This Accepted Author Manuscript (AAM) is copyrighted and published by Elsevier. It is posted here by agreement between Elsevier and the University of Turin. Changes resulting from the publishing process - such as editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms - may not be reflected in this version of the text. The definitive version of the text was subsequently published in FUNGAL BIOLOGY, 115(1), 2011, 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012. You may download, copy and otherwise use the AAM for non-commercial purposes provided that your license is limited by the following restrictions: (1) You may use this AAM for non-commercial purposes only under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND license. (2) The integrity of the work and identification of the author, copyright owner, and publisher must be preserved in any copy. -

Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology 5 (3): 213–247(2015) ISSN 2229-2225 www.creamjournal.org Article CREAM Copyright © 2015 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/cream/5/3/6 Ecology, Distribution Perspective, Economic Utility and Conservation of Coprophilous Agarics (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India Amandeep K1*, Atri NS2 and Munruchi K2 1Desh Bhagat College of Education, Bardwal–Dhuri–148024, Punjab, India. 2Department of Botany, Punjabi University, Patiala–147002, Punjab, India. Amandeep K, Atri NS, Munruchi K 2015 – Ecology, Distribution Perspective, Economic Utility and Conservation of Coprophilous Agarics (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology 5(3), 213–247, Doi 10.5943/cream/5/3/6 Abstract This paper includes the results of eco-taxonomic studies of coprophilous mushrooms in Punjab, India. The information is based on the survey to dung localities of the state during the various years from 2007-2011. A total number of 172 collections have been observed, growing as saprobes on dung of various domesticated and wild herbivorous animals in pastures, open areas, zoological parks, and on dung heaps along roadsides or along village ponds, etc. High coprophilous mushrooms’ diversity has been established and a number of rare and sensitive species recorded with the present study. The observed collections belong to 95 species spread over 20 genera and 07 families of the order Agaricales. The present paper discusses the distribution of these mushrooms in Punjab among different seasons, regions, habitats, and growing habits along with their economic utility, habitat management and conservation. This is the first attempt in which various dung localities of the state has been explored systematically to ascertain the diversity, seasonal availability, distribution and ecology of coprophilous mushrooms. -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Cortinarius Caperatus (Pers.) Fr., a New Record for Turkish Mycobiota

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2015, 15 (1): 86-89 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr., A New Record For Turkish Mycobiota *Ilgaz AKATA1, Şanlı KABAKTEPE2, Hasan AKGÜL3 Ankara University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, 06100, Tandoğan, Ankara Turkey İnönü University, Battalgazi Vocational School, TR-44210 Battalgazi, Malatya, Turkey Gaziantep University, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Arts, 27310 Gaziantep, Turkey *Correspending author: [email protected] Received date: 03.02.2015 Abstract In this study, Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr. belonging to the family Cortinariaceae was recorded for the first time from Turkey. A short description, ecology, distribution and photographs related to macro and micromorphologies of the species are provided and discussed briefly. Keywords: Cortinarius caperatus, mycobiota, new record, Turkey Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr., Türkiye Mikobiyotası İçin Yeni Bir Kayıt Özet Bu çalışmada, Cortinariaceae familyasına mensup Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr. Türkiye’den ilk kez kaydedilmiştir. Türün kısa deskripsiyonu, ekolojisi, yayılışı ve makro ve mikro morfolojilerine ait fotoğrafları verilmiş ve kısaca tartışılmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Cortinarius caperatus, Mikobiyota, Yeni kayıt, Türkiye Introduction lamellae edges (Arora, 1986; Hansen and Cortinarius is a large and complex genus Knudsen, 1992; Orton, 1984; Uzun et al., of family Cortinariaceae within the order 2013). Agaricales, The genus contains According to the literature (Sesli and approximately 2 000 species recognised Denchev, 2008, Uzun et al, 2013; Akata et worldwide. The most common features al; 2014), 98 species in the genus Cortinarius among the members of the genus are the have so far been recorded from Turkey but presence of cortina between the pileus and there is not any record of Cortinarius the stipe and cinnamon brown to rusty brown caperatus (Pers.) Fr. -

Phylogenetic Classification of Trametes

TAXON 60 (6) • December 2011: 1567–1583 Justo & Hibbett • Phylogenetic classification of Trametes SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset Alfredo Justo & David S. Hibbett Clark University, Biology Department, 950 Main St., Worcester, Massachusetts 01610, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Alfredo Justo, [email protected] Abstract: The phylogeny of Trametes and related genera was studied using molecular data from ribosomal markers (nLSU, ITS) and protein-coding genes (RPB1, RPB2, TEF1-alpha) and consequences for the taxonomy and nomenclature of this group were considered. Separate datasets with rDNA data only, single datasets for each of the protein-coding genes, and a combined five-marker dataset were analyzed. Molecular analyses recover a strongly supported trametoid clade that includes most of Trametes species (including the type T. suaveolens, the T. versicolor group, and mainly tropical species such as T. maxima and T. cubensis) together with species of Lenzites and Pycnoporus and Coriolopsis polyzona. Our data confirm the positions of Trametes cervina (= Trametopsis cervina) in the phlebioid clade and of Trametes trogii (= Coriolopsis trogii) outside the trametoid clade, closely related to Coriolopsis gallica. The genus Coriolopsis, as currently defined, is polyphyletic, with the type species as part of the trametoid clade and at least two additional lineages occurring in the core polyporoid clade. In view of these results the use of a single generic name (Trametes) for the trametoid clade is considered to be the best taxonomic and nomenclatural option as the morphological concept of Trametes would remain almost unchanged, few new nomenclatural combinations would be necessary, and the classification of additional species (i.e., not yet described and/or sampled for mo- lecular data) in Trametes based on morphological characters alone will still be possible. -

SP398 for PDF.P65

BULLETIN OF THE PUGET SOUND MYCOLOGICAL SOCIETY Number 398 January 2004 MUSHROOM ODORS R. G. Benedict & D. E. Stuntz growth of bacteria or fungi. One such antibiotic is Diatretyn I, Pacific Search, September 1975 found in Clitocybe diatreta. Some of these chemicals are unstable and release acetylene when they decompose. The sharp orders of Continued from December 2003 Clitocybe inversa and Ripartites helomorpha, especially when wet, The pronounced smell of green corn, not yet chemically defined, are probably due to the decomposition of polyacetylenic com- occurs in the poisonous Inocybe sororia and Inocybe species pounds present. #3399. It is also detected in Cortinarius superbus and Cystoderma Hebeloma crustuliniforme and H. mesophaeum possess a nau- amianthinum. seous combination of radish and the odious organic solvent, pyri- Few species of amanitas have telltale aromas, but one with a sprout- dine. The pretty, lavender-colored Mycena pura and the halluci- ing-potato odor is Amanita porphyria, a non-edible form. The nogenic Psilocybe cyanescens have a mild radish scent. chances of picking a white-gilled, white-spored, potato-scented, As coal is converted to coke, the coal gas vapors contain many mushroom that is not A. porphyria are rare. Mushrooms with simi- odious chemicals in addition to odor-free methane and hydrogen lar odor are Volvariella speciosa and Pluteus cervinus. Both have gases. Mushroom scents arising from Tricholoma inamoenum, T. pink gills and spores, but P. cervinus lacks a volva at the base of sulphureum, and Lepiota bucknallii are said to resemble those in the stem. the unpurified mixture of vapors. Cucumber, farinaceous, and rancid-linseed-oil odors are found in Stinkhorns are highly specialized fleshy fungi with the nauseat- numerous mushrooms. -

INTRODUCTION Biodiversity of Agaricomycetes Basidiomes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CONICET Digital DARWINIANA, nueva serie 1(1): 67-75. 2013 Versión final, efectivamente publicada el 31 de julio de 2013 ISSN 0011-6793 impresa - ISSN 1850-1699 en línea BIODIVERSITY OF AGARICOMYCETES BASIDIOMES ASSOCIATED TO SALIX AND POPULUS (SALICACEAE) PLANTATIONS Gonzalo M. Romano1, Javier A. Calcagno2 & Bernardo E. Lechner1 1Laboratorio de Micología, Fitopatología y Liquenología, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Programa de Plantas Medicinales y Programa de Hongos que Intervienen en la Degradación Biológica (CONICET), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Pabellón II, Piso 4, Laboratorio 7, C1428EGA Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina; [email protected] (author for correspondence). 2Centro de Estudios Biomédicos, Biotecnológicos, Ambientales y de Diagnóstico - Departamento de Ciencias Natu- rales y Antropológicas, Instituto Superior de Investigaciones, Hidalgo 775, C1405BCK Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Abstract. Romano, G. M.; J. A. Calcagno & B. E. Lechner. 2013. Biodiversity of Agaricomycetes basidiomes asso- ciated to Salix and Populus (Salicaceae) plantations. Darwiniana, nueva serie 1(1): 67-75. Although plantations have an artificial origin, they modify environmental conditions that can alter native fungi diversity. The effects of forest management practices on a plantation of willow (Salix) and poplar (Populus) over Agaricomycetes basidiomes biodiversity were studied for one year in an island located in Paraná Delta, Argentina. Dry weight and number of basidiomes were measured. We found 28 species belonging to Agaricomycetes: 26 species of Agaricales, one species of Polyporales and one species of Russulales. -

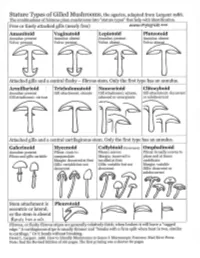

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Molecular Identification of Lepiota Acutesquamosa and L. Cristata

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 12–1007/2013/15–2–313–318 http://www.fspublishers.org Full Length Article Molecular Identification of Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) Based on ITS-rDNA Barcoding from Himalayan Moist Temperate Forests of Pakistan Abdul Razaq1*, Abdul Nasir Khalid1 and Sobia Ilyas1 1Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54590, Pakistan *For correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) collected from Himalayan moist temperate forests of Pakistan were characterized using internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of rNDA, a fungal molecular marker. The ITS-rDNA of both species was analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing. The target region when amplified using universal fungal primers (ITS1F and ITS4) generated 650-650bp fragments. Consensus sequences of both species were submitted for initial blast analysis which revealed and confirmed the identification of both species by comparing the sequences of these respective species already present in the GenBank. Sequence of Pakistani collection of L. acutesquamosa matched 99% with sequences of same species (FJ998400) and Pakistani L. cristata matched 97% with its sequences (EU081956, U85327, AJ237628). Further, in phylogenetic analysis both species distinctly clustered with their respective groups. Morphological characters like shape, size and color of basidiomata, basidiospore size, basidial lengths, shape and size of cheilocystidia of both collections were measured and compared. Both these species have been described first time from Pakistan on morph-anatomical and molecular basis. © 2013 Friends Science Publishers Keywords: Internal transcribed spacers; Lepiotaceous fungi; Molecular marker; Phylogeny Introduction of lepiotaceous fungi (Vellinga, 2001, 2003, 2006). -

Version 1.1 Standardized Inventory Methodologies for Components Of

Version 1.1 Standardized Inventory Methodologies For Components Of British Columbia's Biodiversity: MACROFUNGI (including the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) Prepared by the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Resources Inventory Branch for the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force, Resources Inventory Committee JANUARY 1997 © The Province of British Columbia Published by the Resources Inventory Committee Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Standardized inventory methodologies for components of British Columbia’s biodiversity. Macrofungi : (including the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota [computer file] Compiled by the Elements Working Group of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force under the auspices of the Resources Inventory Committee. Cf. Pref. Available through the Internet. Issued also in printed format on demand. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-3255-3 1. Fungi - British Columbia - Inventories - Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. BC Environment. Resources Inventory Branch. II. Resources Inventory Committee (Canada). Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force. Elements Working Group. III. Title: Macrofungi. QK605.7.B7S72 1997 579.5’09711 C97-960140-1 Additional Copies of this publication can be purchased from: Superior Reproductions Ltd. #200 - 1112 West Pender Street Vancouver, BC V6E 2S1 Tel: (604) 683-2181 Fax: (604) 683-2189 Digital Copies are available on the Internet at: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/ric PREFACE This manual presents standardized methodologies for inventory of macrofungi in British Columbia at three levels of inventory intensity: presence/not detected (possible), relative abundance, and absolute abundance. The manual was compiled by the Elements Working Group of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force, under the auspices of the Resources Inventory Committee (RIC). The objectives of the working group are to develop inventory methodologies that will lead to the collection of comparable, defensible, and useful inventory and monitoring data for the species component of biodiversity. -

Pt Reyes Species As of 12-1-2017 Abortiporus Biennis Agaricus

Pt Reyes Species as of 12-1-2017 Abortiporus biennis Agaricus augustus Agaricus bernardii Agaricus californicus Agaricus campestris Agaricus cupreobrunneus Agaricus diminutivus Agaricus hondensis Agaricus lilaceps Agaricus praeclaresquamosus Agaricus rutilescens Agaricus silvicola Agaricus subrutilescens Agaricus xanthodermus Agrocybe pediades Agrocybe praecox Alboleptonia sericella Aleuria aurantia Alnicola sp. Amanita aprica Amanita augusta Amanita breckonii Amanita calyptratoides Amanita constricta Amanita gemmata Amanita gemmata var. exannulata Amanita calyptraderma Amanita calyptraderma (white form) Amanita magniverrucata Amanita muscaria Amanita novinupta Amanita ocreata Amanita pachycolea Amanita pantherina Amanita phalloides Amanita porphyria Amanita protecta Amanita velosa Amanita smithiana Amaurodon sp. nova Amphinema byssoides gr. Annulohypoxylon thouarsianum Anthrocobia melaloma Antrodia heteromorpha Aphanobasidium pseudotsugae Armillaria gallica Armillaria mellea Armillaria nabsnona Arrhenia epichysium Pt Reyes Species as of 12-1-2017 Arrhenia retiruga Ascobolus sp. Ascocoryne sarcoides Astraeus hygrometricus Auricularia auricula Auriscalpium vulgare Baeospora myosura Balsamia cf. magnata Bisporella citrina Bjerkandera adusta Boidinia propinqua Bolbitius vitellinus Suillellus (Boletus) amygdalinus Rubroboleus (Boletus) eastwoodiae Boletus edulis Boletus fibrillosus Botryobasidium longisporum Botryobasidium sp. Botryobasidium vagum Bovista dermoxantha Bovista pila Bovista plumbea Bulgaria inquinans Byssocorticium californicum