Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Rare Plant Register 2011 Covering VC66 and the Teesdale Part of VC65

Durham Rare Plant Register 2011 Covering VC66 and the Teesdale part of VC65 JOHN L. DURKIN MSc. MIEEM BSBI Recorder for County Durham 25 May Avenue. Winlaton Mill, Blaydon, NE21 6SF [email protected] Contents Introduction to the rare plants register Notes on plant distribution and protection The individual species accounts in alphabetical order Site Index First published 2010. This is the 2011, second edition. Improvements in the 2011 edition include- An additional 10% records, most of these more recent and more precise. One kilometre resolution maps for upland and coastal species. My thanks to Bob Ellis for advice on mapping. The ―County Scarce‖ species are now incorporated into the main text. Hieracium is now included. This edition is ―regionally aligned‖, that is, several species which are county rare in Northumberland, but were narrowly rejected for the Durham first edition, are now included. There is now a site index. Cover picture—Dark Red Helleborine at Bishop Middleham Quarry, its premier British site. Introduction Many counties are in the process of compiling a County Rare Plant Register, to assist in the study and conservation of their rare species. The process is made easier if the county has a published Flora and a strong Biological Records Centre, and Durham is fortunate to have Gordon Graham's Flora and the Durham Wildlife Trust‘s ―Recorder" system. We also have a Biodiversity project, based at Rainton Meadows, to carry out conservation projects to protect the rare species. The purpose of this document is to introduce the Rare Plant Register and to give an account of the information that it holds, and the species to be included. -

Happy Easter to All from Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 193 APRIL 2012 Happy Easter to all from your local news magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD CHURCH NOTICES in Swaledale & Arkengarthdale st 1 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist - Palm Sunday 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist St. Edmund’s Marske Reeth Evangelical Congregational Eucharist 2.00 pm Keld URC 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Reeth Evangelical Congregational th 5 April 7.30 pm Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist & Watch 8.00 pm St. Michael’s Downholme Vigil th 6 April 9.00 am Keld – Corpse Way Walk - Good Friday 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational 12.00 pm St Mary’s Arkengarthdale 2.00 pm St. Edmund’s Marske Devotional Service 3.00 pm Reeth Green Meet 2pm Memorial Hall Open Air Witness th 7 April – Easter Eve 8.45 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton th 8 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s, Muker Eucharist - Easter Sunday 9.30 am St. Andrew’s, Grinton Eucharist St. Michael’s, Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Holy Communion Reeth Methodist All Age Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s Marske Holy Communion Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist 11.15 am St Mary’s Arkengarthdale Holy Communion BCP 2.00 pm Keld URC Holy Communion 4.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational Family Service followed by tea 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist with Gunnerside Choir Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion th 15 April 9.15 am St. -

Consultation Relating to the Structure of Local Government in North Yorkshire

REPORT TO: Council DATE: 14 April 2021 SERVICE AREA: Chief Executive’s Office REPORTING OFFICER: Chief Executive (Wallace Sampson) SUBJECT: Consultation relating to the structure of local government in North Yorkshire WARD/S AFFECTED: ALL DISTRICT FORWARD PLAN REF: N/A 1.0 PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 The purpose of this report is to inform Council of the Secretary of State’s consultation on proposals for Local Government Review; to seek a response to the invitation to Harrogate Borough Council to comment on the North Yorkshire Proposal as consultee; and to consider making any further comment on the East/West proposal that Harrogate Borough Council resolved to submit to the Secretary of State which is now under consultation. 2.0 RECOMMENDATION/S 2.1 Members note that the Secretary of State is consulting on two proposals for re-organisation in the North Yorkshire area. 2.2 Members note that the consultation exercise is not a vote for one proposal over another. It is an opportunity to comment on the merits of both proposals and how they do (or do not) meet the Secretary of State’s guidance criteria. 2.3 Members note that ultimately this is a decision for the Secretary of State who has indicated that the approach to local government reorganisation should be locally led. 2.4 Members note that they can respond in their individual capacity as an elected member and in this regard members are referred to https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/proposals-for-locally-led- reorganisation-of-local-government-in-cumbria-north-yorkshire-and- 1 somerset/consultation-on-proposals-for-locally-led-reorganisation-of-local- government-in-cumbria-north-yorkshire-and-somerset 2.5 Members decide whether they wish the Council to: (a) Respond to the consultation questions in relation to the district council East/West proposal or whether they feel that the existing submission has already addressed the consultation questions; and/or (b) Respond to the consultation questions in relation to the North Yorkshire County Council proposal; and/or (c) Respond to neither. -

Richmondshire District Council Transforms Email Security and Data Privacy Footing to Refocus on Innovation

Case Study Richmondshire District Council Transforms Email Security and Data Privacy Footing to Refocus on Innovation The North Yorkshire-based council transformed its email security and At a Glance data privacy footing while slashing Company: email management time to allow a • Supports 220 email users in 16 sites. focus on innovation in technology- • The council was seeking to secure its Exchange enabled service delivery • 2016 environment against advanced email threats including impersonation attacks. Richmondshire District Council is a local government body in North Yorkshire, • It needed a secure archive to take the pressure off local storage. England. It covers a large northern area of the Yorkshire Dales and must consistently • Content controls were required to prevent data leaks and aide GDPR compliance. deliver a wide range of public services – from revenues and benefits and homelessness Richmondshire District Council is a local government body in North Yorkshire, England. It provides the services to environmental health, planning, local population with a wide range of public services waste and recycling, and more. The – from revenues and benefits and homelessness services to environmental health, planning, waste and scale of the council’s operations, which recycling, and more. are headquartered in Richmond with 14 Products: smaller sites, means email is a primary Email Security, Archiving communicationtool both within the council and to interact with the public. www.mimecast.com | ©2020 Mimecast | All Rights Reserved | UK-1656 Richmondshire District Council Transforms Email Security and Data Privacy Footing to Refocus on Innovation For ICT & Business Change Manager, “We handle all the emails ourselves, from Graeme Thistlethwaite, that means keeping Exchange at the backend right across the email on is a major priority: “It is our main board for around 220 users,” he explained. -

Richmondshire District Council

What happens next? We have now completed our review of Richmondshire District Council. April 2018 Summary Report The recommendations must now be approved by Parliament. A draft order - the legal document which brings The full report and detailed maps: into force our recommendations - will be laid in Parliament. consultation.lgbce.org.uk www.lgbce.org.uk Subject to parliamentary scrutiny, the new electoral arrangements will come into force at the local elections in @LGBCE May 2019. Our recommendations: The table lists all the wards we are proposing as part of our final recommendations along with the number of Richmondshire voters in each ward. The table also shows the electoral variances for each of the proposed wards, which tells you how we have delivered electoral equality. Finally, the table includes electorate projections for 2023, so you can see the impact of the recommendations for the future. District Council Final recommendations on the new electoral arrangements Ward Number of Electorate Number of Variance Electorate Number of Variance Name: Councillors: (2017): Electors per form (2023): Electors per from Councillor: average % Councillor: Average % Catterick & 3 4,783 1,594 7% 5,008 1,669 4% Brompton-on- Swale Colburn 2 2,245 1,123 -25% 3,228 1,614 1% Croft & 2 2,872 1,436 -4% 2,949 1,475 -8% Middleton Tyas Gilling West 1 1,692 1,692 13% 1,713 1,713 7% Hawes, High 1 1,504 1,504 1% 1,522 1,522 -5% Abbotside & Upper Swaledale Hipswell 2 2,957 1,479 -1% 3,058 1,529 -4% Leyburn 2 2,934 1,467 -2% 3,266 1,633 2% Lower 1 1,455 1,455 -3% 1,462 1,462 -8% Who we are: Why Richmondshire? Swaledale & ■ The Local Government Boundary Commission for ■ Richmondshire District Council submitted a Arkengarthdale England is an independent body set up by Parliament. -

DM-15-02063-Turbine 2 Punder Gill, Item 5B

Planning Services COMMITTEE REPORT APPLICATION DETAILS APPLICATION NO: DM/15/02063/FPA Erection of turbine no. 2 a 46.3m tip height turbine with FULL APPLICATION DESCRIPTION: associated access and sub-station (one of two turbines sought under two planning applications) NAME OF APPLICANT: Mr M Thompson ADDRESS: Pundergill, Rutherford Lane, Brignall, Barnard Castle ELECTORAL DIVISION: Barnard Castle West Henry Jones, Senior Planning Officer CASE OFFICER: [email protected], 03000 263960 DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE AND PROPOSALS The Site 1. The application site comprises agricultural land that lies approximately 180m to the south of the A66 and 200m to the west of Rutherford Lane. The watercourse of Punder Gill runs roughly east west to the south of the site. A large copse of trees stands immediately to the west of the site. 2. The nearest residential properties outwith the applicants control are situated approximately 215m to the north east at North Bitts, 520m to the east at Dent House Farm, 395m to the west at South Flats Farm and 565m to the south at Timpton Hill Farm. Dent House farmhouse and its adjacent outbuilding is a grade II listed building. The nearest Public Right of Way (PROW) is No.5 Brignall which commences/terminates on the eastern side of Rutherford Lane 220m south east of the application site. 3. The south eastern extent of the North Pennines AONB lies approximately 2.1km to the south of the site, whilst the site itself is designated as an Area of High Landscape value in the Teasdale Local Plan. The nearest site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) lies approximately 1.5km to the west of the site. -

Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG Profile

January 2019 North Yorkshire Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2019 Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG Profile Introduction This profile provides an overview of population health needs in Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG (HRW CCG). Greater detail on particular topics can be found in our Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) resource at www.datanorthyorkshire.org which is broken down by district. This document is structured into five parts: population, deprivation, disease prevalence, hospital admissions and mortality. It identifies the major themes which affect health in HRW CCG and presents the latest available data, so the dates vary between indicators. Summary Life expectancy is higher than England. For 2011-2015, female life expectancy in HRW CCG is 84.2 years (England: 83.1), and male life expectancy is more than three years lower than for females at 80.9 years (England: 79.4) [1]. There is a high proportion of older people. In 2017, 25.1% of the population was aged 65 and over (36,100), higher than national average (17.3%). Furthermore over 4,300 (3.0%) were age 85+, compared with 2.3% in England. [2] Some children grow up in relative poverty. In 2015, there were 10.8% of children aged 0-15 years living in low income families, compared with 19.9% in England [1]. There are pockets of deprivation. Within the CCG area, 3 Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) out of a total of 95 are amongst the 20% most deprived in England. One of them is amongst the 10% most deprived in England, in the Whitby West Cliff ward [3]. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Contents Hawthorn Dene, 1, 5-Jul-1924

Northern Naturalists’ Union Field Meeting Reports- 1924-2005 Contents Hawthorn Dene, 1, 5-jul-1924 .............................. 10 Billingham Marsh, 2, 13-jun-1925 ......................... 13 Sweethope Lough, 3, 11-jul-1925 ........................ 18 The Sneap, 4, 12-jun-1926 ................................... 24 Great Ayton, 5, 18-jun-1927 ................................. 28 Gibside, 6, 23-jul-1927 ......................................... 28 Langdon Beck, 7, 9-jun-1928 ............................... 29 Hawthorn Dene, 8, 5-jul-1928 .............................. 33 Frosterley, 9 ......................................................... 38 The Sneap, 10, 1-jun-1929 ................................... 38 Allenheads, 11, 6-july-1929 .................................. 43 Dryderdale, 12, 14-jun-1930 ................................. 46 Blanchland, 13, 12-jul-1930 .................................. 49 Devil's Water, 14, 15-jun-1931 ............................. 52 Egglestone, 15, 11-jul-1931 ................................. 53 Windlestone Park, 16, June? ............................... 55 Edmondbyers, 17, 16-jul-1932 ............................. 57 Stanhope and Frosterley, 18, 5-jun-1932 ............. 58 The Sneap, 19, 15-jul-1933 .................................. 61 Pigdon Banks, 20, 1-jun-1934 .............................. 62 Greatham Marsh, 21, 21-jul-1934 ........................ 64 Blanchland, 22, 15-jun-1935 ................................ 66 Dryderdale, 23, ..................................................... 68 Raby Park, -

July 2019 at 7.00Pm

Minutes of a meeting of Leyburn Town Council held in the Oak Room, Thornborough Hall on Monday, 15th July 2019 at 7.00pm PRESENT: Cllr Alderson Cllr Beswick Cllr Holder Cllr Medley Cllr Sanderson Cllr Waites Cllr Walker IN ATTENDANCE: Cllr Sedgwick Mrs C Smith- Clerk Ms Rebecca Hurst- Deputy Clerk Representatives from the Police and Hambleton & Richmondshire Fire Service Four members of the public 4229. PUBLIC REPRESENTATIONS Residents raised concerns over the increase in dog fouling in the Rowan Court area and expressed dissatisfaction with the standard of the verges cutting. Cllr Sedgewick reported back to the Council on a meeting attended with the highways improvement manager to discuss the safety of Moor rd. Highways responded to the following four proposed solutions to improve pedestrian safety; 1. A painted footway on the road –May give false sense of security to pedestrians. 2. Waiting restrictions painted on the carriageway-This would prevent parking on the road, however the highways consider that the parked cars act as traffic calming and slow the traffic down. 3. A pedestrian activated sign 4. Creating a priority over oncoming vehicles- This may cause congestion of traffic backing up the road. Cllr Sedgewick concluded by informing the Council that the highways do not consider Moor Road safety as a high priority, therefore no further steps will be taken at the moment due to financial restrictions. Cllr Sedgewick also updated the council that Metcalfe farms have installed signage at the end of their road instructing traffic to turn right to try to reduce the traffic on Moor Road. -

Flora of Deepdale 2020

Flora of Deepdale 2020 John Durkin MSC. MCIEEM www.durhamnature.co.uk [email protected] Introduction Deepdale is a side valley of the River Tees, joining the Tees at Barnard Castle. Its moorland catchment area is north of the A66 road across the Pennines. The lower three miles of the dale is a steep-sided rocky wooded valley. The nature reserve includes about half of this area. Deepdale has been designated as a Local Wildlife Site by Durham County Council. Deepdale is one of four large (more than 100 hectare) woods in Teesdale. These are important landscape-scale habitat features which I have termed “Great Woods”. The four Teesdale Great Woods are closely linked to each other, and are predominantly “ancient semi-natural” woods, both of these features increasing their value for wildlife. The other three Teesdale Great Woods are the Teesbank Woods upstream of Barnard Castle to Eggleston, the Teesbank Woods downstream from Barnard Castle to Gainford, and the woods along the River Greta at Brignall Banks. The habitats and wildlife of the Teesdale four are largely similar, with each having its particular distinctiveness. The Teesbank Woods upstream of Barnard Castle have been described in a booklet “A guide to the Natural History of the Tees Bank Woods between Barnard Castle and Cotherstone” by Margaret Morton and Margaret Bradshaw. Most of these areas have been designated as Local Wildlife Sites. Two areas, “Shipley and Great Wood” near Eggleston, and most of Brignall Banks have the higher designation, “Site of Special Scientific Interest”. There are about 22 Great Woods in County Durham, mainly in the well- wooded Derwent Valley, with four along the River Wear, three large coastal denes and the four in Teesdale. -

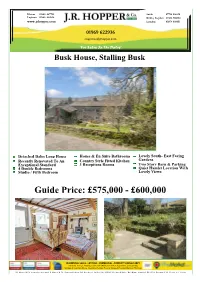

Guide Price: £575000

Hawes 01969 667744 Settle 07726 596616 Leyburn 01969 622936 Kirkby Stephen 07434 788654 www.jrhopper.com London 02074 098451 01969 622936 [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” Busk House, Stalling Busk Detached Dales Long House House & En Suite Bathrooms Lovely South- East Facing Recently Renovated To An Country Style Fitted Kitchen Gardens Exceptional Standard 3 Receptions Rooms Two Story Barn & Parking 4 Double Bedrooms Quiet Hamlet Location With Studio / Fifth Bedroom Lovely Views Guide Price: £575,000 - £600,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Busk House, Stalling Busk, Askrigg DESCRIPTION Busk House is traditional Dales long house located in the little known valley of Raydale in Upper Wensleydale. Stalling Busk is a pretty farming village with a small church and is situated at the south end of Semerwater, the second largest natural lake in Yorkshire, and a haven for wildlife & flowers. It is only 3 miles from the village of Bainbridge with a primary school & chapel, pub, butcher's shop, garage & shop and 5 miles from the Market Town of Hawes with a good range of amenities including doctor's surgery and school. The property is believed to date back to 1685. It boasts a wealth of charm with its original character features including stone mullions, original cheese shelves, beams and feature wall niches.