Queer Rap Discourse in Online Music Culture by Erika Ibrahim a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Program in G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adam4adam Asianfriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars The

#1035 nightspots February 2, 2011 Adam4Adam AsianFriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars 2 The Tongue Upright Citizen Chica Grande Jeepers Piepers 5sum Bent Boriqua Mr. Perfect Stranglers 5 1 Minerva Wrecks Circuit Daddy The Continental Shameless Boi-lesque ASS Da Gay Mayor Adam5Adam 1 Happy The richness Valentines, of Amanda Nightspots-style. Lepore. page 13 page 11 That Guy by Kirk Williamson In lieu of my column this week... [email protected] JOSEPH J. MAGGIO Joseph J. Maggio, age 58, passed away suddenly at his home on January 17. Best Friend and life partner of Jimmy Keup, Joe was the love of his life. Devoted son to the late Tina Riotto and the late Bartolo Maggio; brother of Maria (David) Guzik; and uncle to Mathew. Joe was a graduate of St. Partrick High School, received his Bachelor’s degree from Loyola University and his Master’s degree from Northeastern University. He began his long career as a teacher at Notre Dame High School for Girls in 1977. For the last 20 years, Joe taught math at St. Ignatius College Prep, and was honored to serve as coach of their Math Team. Among his other passions in life were real estate development, The Jackhammer Bar and The Ashland Arms Guest House. A Celebration of Life will take place Sat., February 12, 2011, from 2-4 p.m. at Unity in Chicago, 1925 W. Thome Avenue, Chicago, IL 60660. The celebration will then move to Jackhammer, 6406 N. Clark St. Donations to Alzheimer’s Association would be appreciated. PUBLISHER Tracy Baim ASSISTANT PUBLISHER Terri Klinsky nightspots MANAGING EDITOR -

«Es Gibt Keinen Schwulen Rap» | Norient.Com 7 Oct 2021 18:15:11

«Es gibt keinen schwulen Rap» | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 18:15:11 «Es gibt keinen schwulen Rap» by Jonathan Fischer Der New Yorker Rapper Khalif Diouf alias Le1f ist schwul und mischt mit Witz und knalligen Videos den Hip-Hop auf. Als Aktivist für LGTB-Rechte sieht sich der Sohn senegalesischer Einwanderer aber nicht – und Musikjournalisten, so empfiehlt er, sollten sich weniger mit seiner sexuellen Identität und mehr mit seinen Songs beschäftigen. Eine bearbeitete Version dieses Artikels erschien im Norient Buch Seismographic Sounds (Info und Bestellmöglichkeit hier). Das Interview fängt nicht gut an. Nachdem der Fotograf den schlaksigen Afroamerikaner darum gebeten hat, doch bitte – «nur für ein paar Bilder» – eine blonde Perücke aufzusetzen, stürmt Khalif Diouf alias Le1f wütend Richtung Ausgang seines Münchner Hotels: «Ich bin ein Rapper und keine https://norient.com/stories/le1f Page 1 of 5 «Es gibt keinen schwulen Rap» | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 18:15:11 Drag-Queen!» Und was er auf dem Kopf trage, solle man bitte sehr seiner eigenen Regie überlassen. Erst das Versprechen, ernsthaft über seine Texte zu reden, holt ihn zurück. Ein paar Fragen später lümmelt Le1f entspannt auf der Couch und lacht über die Aufregung, die seine Person im Showbusiness auslöst: «Warum kommt niemand mal auf die Idee, mich mit Little Richard oder Sylvester in eine Reihe zu stellen? Die waren auch schwul und schwarz. Und sehr erfolgreiche Entertainer.» Dabei teilt der junge New Yorker das Dilemma aller offen schwulen Rapper: Die Medien reduzieren sie nur allzu gern auf ihre Sexualität, messen sie an ihrem Provokationswert für die Hiphop-Welt. -

IZZY OCAMPO New York, NY | (917) 480-0360 | [email protected]

IZZY OCAMPO New York, NY | (917) 480-0360 | [email protected] EDUCATION 2014 Middlebury College Middlebury, VT Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude, Chemistry GPA: 3.6/4.0 HONORS 2010—2014 Posse Foundation Full-Tuition Leadership Scholarship to Middlebury College LECTURES & WORKSHOPS 2016 Recess Art New York, NY brujas x stud1nt: Home Studio Recording & Sound Design Workshop 2016 Vassar College Poughkeepsie, NY Creative Approaches to Electronic Production 2016 The New School New York, NY Movement and Process in Electronic Production EXPERIENCE Fall 2016- Present Hyperballad Music Brooklyn, NY A&R ▪ Scout emerging and leading talent for 7” series and liaise between artist’s team and Hyperballad ▪ Build Hyperballad’s brand as a creative cultural hub and cultivate relevant industry partnerships through curatorial programming of unique music products and events Summer 2016-Present Whimsical Raps New York, NY Operations Manager ▪ Manage lifecycle of four modular synthesizers from parts sourcing, manufacturing, assembly, shipment, to repairs ▪ Prepare and coordinate invoices and purchase orders for dozens of distributors, manufacturers, and buyers ▪ Responsible for hand assembly of faceplates, knobs, circuit boards and product packaging and small soldering repairs ▪ Calibrate and quality control each module before shipment Summer 2016 Hyperballad Music Brooklyn, NY Recording Engineer Intern ▪ Prepared recording consoles, tape machine, patchbay, instruments, mics, outboard gear, and DAWs for tracking sessions ▪ Assisted engineers with tracking -

A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory ISSN: 0740-770X (Print) 1748-5819 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange To cite this article: Savannah Shange (2014) A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 24:1, 29-45, DOI: 10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 Published online: 14 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2181 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwap20 Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 1, 29–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange* Department of Africana Studies and the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States This article explores the deployment of race, queer sexuality, and femme gender performance in the work of rapper and pop musical artist Nicki Minaj. The author argues that Minaj’s complex assemblage of public personae functions as a sort of “bait and switch” on the laws of normativity, where she appears to perform as “straight” or “queer,” while upon closer examination, she refuses to be legible as either. Rather than perpetuate notions of Minaj as yet another pop diva, the author proposes that Minaj signals the emergence of the femmecee, or a rapper whose critical, strategic performance of queer femininity is inextricably linked to the production and reception of their rhymes. -

Lab Data.Pages

Day 1 The Smiths Alternative Rock 1 6:48 Death Day Dark Wave 1 4:56 The KVB Dark Wave 1 4:11 Suuns Dark Wave 6 35:00 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 2 8:09 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:43 HTRK Indie Rock 9 40:35 TV On The Radio Indie Rock 1 3:26 Warpaint Indie Rock 19 110:47 Joy Division Post-Punk 1 3:54 Lebanon Hanover Post-Punk 1 4:53 My Bloody Valentine Post-Punk 1 6:59 The Soft Moon Post-Punk 1 3:14 Sonic Youth Post-Punk 1 4:08 18+ R&B 6 21:46 Massive Attack Trip Hop 2 11:41 Trip-Hop 11:41 Indie Rock 158:31 R&B 21:46 Post-Punk 22:15 Dark Wave 52:16 Alternative Rock 6:48 Day 2 Blonde Redhead Alternative Rock 1 5:19 Mazzy Star Alternative Rock 1 4:51 Pixies Alternative Rock 1 3:31 Radiohead Alternative Rock 1 3:54 The Smashing Alternative Rock 1 4:26 Pumpkins The Stone Roses Alternative Rock 1 4:53 Alabama Shakes Blues Rock 3 12:05 Suuns Dark Wave 2 9:37 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 1 3:48 Com Truise Electronic 2 7:29 Les Sins Electronic 1 5:18 A Tribe Called Quest Hip Hop 1 4:04 Best Coast Indie Pop 1 2:07 The Drums Indie Pop 2 6:48 Future Islands Indie Pop 1 3:46 The Go! Team Indie Pop 1 4:15 Mr Twin Sister Indie Pop 3 12:27 Toro y Moi Indie Pop 1 2:28 Twin Sister Indie Pop 2 7:21 Washed Out Indie Pop 1 3:15 The xx Indie Pop 1 2:57 Blood Orange Indie Rock 6 27:34 Cherry Glazerr Indie Rock 6 21:14 Deerhunter Indie Rock 2 11:42 Destroyer Indie Rock 1 6:18 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:33 Kurt Vile Indie Rock 1 6:19 Real Estate Indie Rock 2 10:38 The Soft Pack Indie Rock 1 3:52 Warpaint Indie Rock 1 4:45 The Jesus and Mary Post-Punk 1 3:02 Chain Joy Division Post-Punk -

Collective Community Chicago Who We Are

Collective Community Chicago Who We Are .. Them Flavors connects curious and open mined creatures with new and progressive forms of art, music, and creation - Giving individuals an inviting environment to reflect, examine and grow one’s perspectives and personalities. … What we do them Flavors is a full-production event collective, both producing and promoting on the rise musicians and artists with club nights, underground parties, record releases, and community involvement. ’ve Been .. Where We As a Chicago-based collective, we pride ourselves on what motivates and moves our fellow beings in the midwest region, but are also mindful of the art and movements of other regions of the great planet we all share as one. Chicago Them flavors were early responders to the footwork movement - the offspring of the native genre, juke. we stay rooted in chicago house music and celebrate its legacy in almost every Event we promote. Detroit we pay homage to our sister, Detroit often with promoting techno music and underground parties. In May 2016, we collaborated with Detroit-local hip hop promoters 777 Renegade , and paired their programming with a bit of chicago footwork, Producing a cross-region and cross - genre function. Texas Marfa, Frontiers red bull Each guest was a result of a thoughtful and hand picked curation process led by t he team at Red Bull to identify those powerful agents of change who are emerging as the disruptors and innovators in their respective cities. Each day was a series of conversations with sciences, academics, and professionals in a variety of disciplines to push innovation and creative thinking, wth the goal of catalyzing new ideas and opportunities in nightlife. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping. -

Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health Camille A

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 43 Number 3 Mental Health, the Law, & the Urban Article 4 Environment 2016 Frontlines: Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health Camille A. Nelson Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Recommended Citation Camille A. Nelson, Frontlines: Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health, 43 Fordham Urb. L.J. 615 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol43/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTLINES: POLICING AT THE NEXUS OF RACE AND MENTAL HEALTH Camille A. Nelson* ABSTRACT The last several years have rendered issues at the intersection of race, mental health, and policing more acute. The frequency and violent, often lethal, nature of these incidents is forcing a national conversation about matters which many people would rather cast aside as volatile, controversial, or as simply irrelevant to conversations about the justice system. It seems that neither civil rights activists engaged in the work of advancing racial equality nor disability rights activists recognize the potent combination of negative racialization and mental illness at this nexus that bring policing practices into sharp focus. As such, the compounding dynamics and effects of racism, mental health, and policing remain underexplored and will be the foci of this Article. -

NEITHER QUEER NOR THERE; Categories, Assemblages, Transformations

NEITHER QUEER NOR THERE; Categories, Assemblages, Transformations TEXT/MATT MORRIS Big false eyelashes being batted and white rose and Ryan Lewis' chart-topping gay rights hip- ics full of risqué same-sex desire and endlessly blossoms planted high in a naked man's but- hop anthem), these artists were the ones who fanciful permutations of gender expressions tocks. Vivid gender fiuidity and non-normative compelled my photographer friend Michael running through layered musical sensibilities sexual practices. Bearded ladies, anime, and Reece to say that this cultural moment is what that draw from LiF Kim's hard femme bitch- Billie Holiday. Confident passes through club he'd been waiting for his whole life. Friends and ery and richly textured cloud rap. But while scenes and across dance floors. Twerking, strip- colleagues across the country concurred. my approach to this music is a queer one, my ping, voguing. Haute couture and the superhe- Lelf, Mykki Blanco, House of LaDosha, Cakes research into these various artists and discus- roic erotic futurism of BCALLA fashions. Lelf's Da Killa, and Big Momma are among a bur- sions with them reveal certain tensions with otherworldly pronouncement: "This mattress geoning new wave of artists who have been queer identification. If these musical projects is Atlantis." Bougie, rächet, skag drag. House of contentiously identified with a turn toward are adamant about portraying their own sex- LaDosha's frankly forceful "It's not just bitches, "queer rap" over the past several years. The ualities and sexual fantasies, there is also the it's witches/The seventh layer of Bushwick/ phantasmagoria called into being by this refusal to be delimited only to the homosexu- They ride a wicked dick, they keep it light as group is built from a wild web of references alities that "queer" is commonly used to con- a feather and stiff as a board." Further neopa- that imagines new directions for rap and hip- note. -

Mike Epps Slated As Host for This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS

Mike Epps Slated As Host For This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS G.O.O.D. MUSIC'S KANYE WEST LEADS WITH 17 IMPRESSIVE NOMINATIONS; 2CHAINZ FOLLOWS WITH 13 AND DRAKE ROUNDS THINGS OUT WITH 11 NODS SIX CYPHERS TO BE INCLUDED IN THIS YEAR'S AWARDS TAPING AT THE BOISFEUILLET JONES ATLANTA CIVIC CENTER IN ATLANTA ON SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2012; NETWORK PREMIERE ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2012 AT 8:00 PM* NEW YORK, Sept. 12, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- BET Networks' flagship music variety program, "106 & PARK," officially announced the nominees for the BET HIP HOP AWARDS (#HIPHOPAWARDS). Actor and comedian Mike Epps (@THEREALMIKEEPPS) will once again host this year's festivities from the Boisfeuillet Jones Atlanta Civic Center in Atlanta on Saturday, September 29, 2012 with the network premiere on Tuesday, October 9, 2012 at 8:00 pm*. Mike Epps completely took-over "106 & PARK" today to mark the special occasion and revealed some of the notable nominees with help from A$AP Rocky, Ca$h Out, DJ Envy and DJ Drama. Hip Hop Awards nominated artists A$AP Rocky and Ca$h Out performed their hits "Goldie" and "Cashin Out" while nominated deejay's DJ Envy and DJ Drama spun for the crowd. The BET HIP HOP AWARDS Voting Academy is comprised of a select assembly of music and entertainment executives, media and industry influencers. Celebrating the biggest names in the game, newcomers on the scene, and shining a light on the community, the BET HIP HOP AWARDS is ready to salute the very best in hip hop culture. -

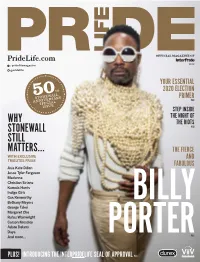

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

SXSW2016 Music Full Band List

P.O. Box 685289 | Austin, Texas | 78768 T: 512.467.7979 | F: 512.451.0754 sxsw.com PRESS RELEASE - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SXSW Music - Where the Global Community Connects SXSW Music Announces Full Artist List and Artist Conversations March 10, 2016 - Austin, Texas - Every March the global music community descends on the South by Southwest® Music Conference and Festival (SXSW®) in Austin, Texas for six days and nights of music discovery, networking and the opportunity to share ideas. To help with this endeavor, SXSW is pleased to release the full list of over 2,100 artists scheduled to perform at the 30th edition of the SXSW Music Festival taking place Tuesday, March 15 - Sunday, March 20, 2016. In addition, many notable artists will be participating in the SXSW Music Conference. The Music Conference lineup is stacked with huge names and stellar latebreak announcements. Catch conversations with Talib Kweli, NOFX, T-Pain and Sway, Kelly Rowland, Mark Mothersbaugh, Richie Hawtin, John Doe & Mike Watt, Pat Benatar & Neil Giraldo, and more. All-star panels include Hired Guns: World's Greatest Backing Musicians (with Phil X, Ray Parker, Jr., Kenny Aranoff, and more), Smart Studios (with Butch Vig & Steve Marker), I Wrote That Song (stories & songs from Mac McCaughan, Matthew Caws, Dan Wilson, and more) and Organized Noize: Tales From the ATL. For more information on conference programming, please go here. Because this is such an enormous list of artists, we have asked over thirty influential music bloggers to flip through our confirmed artist list and contribute their thoughts on their favorites. The 2016 Music Preview: the Independent Bloggers Guide to SXSW highlights 100 bands that should be seen live and in person at the SXSW Music Festival.