1945 March 26-April 1 Bloody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Hansen Memorial Park Somerville, MA

Community Meeting #1 Henry Hansen Memorial Park Somerville, MA AGENDA • Introductions • Design Schedule • History • Existing Conditions & Site Analysis • Possible Precedents • Questions for Discussion Monday March 26, 2018 PROJECT OVERVIEW HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC PROJECT OVERVIEW INTRODUCTIONS City of Somerville Bryan Bishop, Commissioner of Veterans’ Services CBA Landscape Architects LLC D.J. Chagnon, Principal-in-Charge & Project Manager Jessica Choi & Liz Thompson, Staff Landscape Designers HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC DESIGN SCHEDULE PROJECT OVERVIEW Community Meeting 1 (March 26, 2018): Present history, site analysis, and precedents. Gather community input, and develop wish list to guide Schematic Designs for future meetings. Community Meeting 2 (Late April 2018:) Present Schematic Design Alternatives based on first meeting input. Community review and discussion, with the goal of developing a final Preferred Design Plan. Community Meeting 3 (Early June 2018): Present Definitive Design for park construction, including features and site furnishings based on community discussion at Meeting 2. With community input, discuss project budget, bidding process, suggested Alternates, and prioritize strategy to maximize budget. Design Development (Summer 2018): CBA will further develop and refine Definitive Design. Funding Application (Fall 2018): City of Somerville will apply for Funding. Construction Documents (Winter - Spring 2019): CBA will finalize Definitive Design and suggested Alternates into detailed Construction Documents suitable for bidding purposes. Construction Start (Late Spring - Summer 2019) HENRY HANSON MEMORIAL PARK - Somerville, MA | Community Meeting 1 CBA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS LLC VISION PROJECT OVERVIEW To renovate Henry Hansen Park - a small gem of Somerville’s park system with an important story to tell in both local and national history. -

Henry S. Smith World War Ii Letters, 1943-1946

Collection # M 0939 HENRY S. SMITH WORLD WORLD WAR II LETTERS, 1943–1946 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Tyler Nowell September 2007 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF Manuscript Materials: 1 document case COLLECTION: Visual Materials: 8 folders of photographs COLLECTION 1943–1946 (bulk 1944–1946) DATES: PROVENANCE: Charles, Kritsch, Indianapolis, Indiana, August 1999 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE None FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 1999.0589 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Henry S. Smith was born on February 20, 1914 in Indiana. He married Alice Kritsch sometime in the late 1930s. Smith enlisted in the Unites States Army on March 3, 1944 to fight in World War II. When he enlisted he stated he had four years of high school and that his occupation was as a physical therapy technician or chain store manager. Smith served as a truck driver in C Company of the 136th Ordnance Maintenance Battalion, which was later changed to an Armored Ordnance Maintenance Battalion in April 1945. The battalion was in the 14th Armored Division, which was in the 7th Army for much of the war under General Alexander M. Patch. Late in the war the division was moved to the 3rd Army under General George Patton. Henry Smith was a private until early November 1944. At this time he was promoted to Technician Fifth (T/5), which is equal to a corporal. -

Spearhead-Fall-Winter-2019.Pdf

Fall/Winter 2019 SpearheadOFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the 5TH MARINE DIVISION NEWS“Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue” ASSOCIATION OCTOBER 22 - 25, 2020 71ST ANNUAL REUNION DALLAS, TEXAS Sons of Iwo vets take the helm of FMDA Bruce Hammond and statue in Semper Fi Tom Huffhines, both Memorial Park at the native Texans and sons Marine Corps War of Iwo Jima veterans Museum at Quantico, who previously (Triangle) Va., and served as Association had long worked with presidents and reunion the FMDA. hosts, were selected to Continuing his lead the Fifth Marine father’s work with the Division Association Association, President as president and vice Bruce Hammond said, president, respectively, “It is important that we for the next year. channel our passion, Additionally, move forward and lifetime FMDA mem- President Bruce Hammond and Vice President Tom Huffhines focus on our mission ber, Army helicopter for our Marine veterans.” pilot and Vietnam veteran John Powell volunteered to Vice President John Huffhines agreed and said, host the next FMDA reunion from Oct. 22-25, 2020, in “Communication with the membership, as good and Dallas. as often as possible, is extremely key to its existence. Hammond’s father, Ivan (5th JASCO), hosted the Stronger fundraising ideas and efforts should be the 2016 reunion in San Antonio, Texas, when John Butler main thing on each of our agendas.” was president, and in Houston, Texas, in 2009 when he Hammond graduated from the University of Texas, was president himself. Austin, in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Huffhines’ father, John (HS 2/3), hosted the 2006 He worked for 24 years as a well-site drilling-fluids reunion in Irving, Texas, when he was president. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

Third Division World War II Vol One.Pdf

THIRD INFANTRY DIVISION THE VICTORY PATH THROUGH FRANCE AND GERMANY VOLUME ONE 'IVG. WILLIAM MOHR THE VICTORY PATH THROUGH FRANCE AND GERMANY THIRD INFANTRY DIVISION - WORLD WAR II VOLUME ONE A PICTORIAL ACCOUNT BY G. WILLIAM MOHR ABOUT THE COVER There is nothing in front of the Infantry in battle except the enemy. The Infantry leads the way to attack and bears the brunt of the enemy's attack. The primary purpose of the Infan try is to close with the enemy in hand-to-hand fighting. On the side of a house, tommy gunners of this Infantry patrol, 1st Special Service Froce Patrol, one of the many patrols that made possible the present offensive in Italy by feeling out the enemy and discovering his defensive strength, fire from the window of an adjoining building to blast Nazis out. The scene is 400 yards from the enemy lines in the Anzio area, Italy. Fifth Army, 14 April, 1944. The 3rd Infantry Division suffered 27,450 casualties and 4,922 were killed in action. 2 - Yellow Beach, Southern France, August, 1944 3 - Marseilles, France, August, 1944 4 - Montelimar, France, August, 1944 5 - Cavailair, France, August, 1944 6 - Avignon, France, August, 1944 7 - Lacroix, France, August, 1944 8 - Brignolles, France, August, 1944 9 -Aix-En-Provence, France, August, 1944 12 - St. Loup, France, August, 1944 13 - La Coucounde, France, August, 1944 14 - Les Loges Neut, France, August, 1944 15 - Besancon, France, September, 1944 18 - Loue River, Ornans, France, September, 1944 19 - Avonne, France, Septem&er, 1944 20 - Lons Le Sounier, France, September, 1944 21 - Les Belles-Baroques, France, September, 1944 22 - St. -

Dedication Marine Corps War Memorial

• cf1 d>fu.cia[ CJI'zank 'Jjou. {tom tf'u. ~ou.1.fey 'Jou.ndation and c/ll( onumE.nt f]:)E.di catio n eMu. §oldie. ~~u.dey 9Jtle£: 9-o't Con9u~ma.n. ..£a.uy J. dfopkira and .:Eta(( Captain §ayfc. df. cf?u~c., r"Unitc.d 2,'tat~ dVaay cf?unac. c/?e.tiud g:>. 9 . C. '3-t.ank.fin c.Runyon aow.fc.y Captain ell. <W Jonu, Comm.andtn.9 D((kn, r"U.cS.a. !lwo Jima ru. a. o«. c. cR. ..£ie.utenaJZI: Coforuf c.Richa.t.d df. Jetl, !J(c.ntucky cflit dVa.tionaf §uat.d ..£ieuienant C!ofond Jarnu df. cJU.affoy, !J(wtucky dVa.tional §uat.d dU.ajo"< dtephen ...£. .::Shivc.u r"Unit£d c:Sta.tu dU.a.t.in£ Cotp~ :Jfu. fln~pul:ot.- fl~huclot. c:Sta.{{. 11/: cJU.. P.C.D., £:ci.n9ton., !J(!:J· dU.a1tn c:Sc.1.9c.a.nt ...La.ny dU.a.'ltin, r"Unltc.d c:Stal£~ dU.a.t.lnc. Cot.pi cR£UW£ £xi1t9ton §t.anite Company, dU.t.. :Daniel :be dU.at.cUJ (Dwnc.t.} !Pa.t.li dU.onurncn.t <Wot.ki, dU.t. Jim dfifk.e (Dwn£"tj 'Jh£ dfonowbf£ Duf.c.t. ~( !J(£ntucky Cofone£. <l/. 9. <W Pof.t dVo. 1834, dU.t.. <Wiffu df/{~;[ton /Po1l Commarzdz.t} dU.t.. Jarnu cJU.. 9inch Jt.. dU.t.. Jimmy 9tn.ch. dU.u. dVo/J[~; cflnow1m£th dU.u. 'Je.d c:Suffiva.n dU.t.. ~c. c/?odt.'9uc.z d(,h. -

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots by NATHANIEL S. PATCH n the morning of September 2, 1944, the submarine USS OFinback was floating on the surface of the Pacific Ocean—on lifeguard duty for any downed pilots of carrier-based fighters at- tacking Japanese bases on Bonin and Volcano Island. The day before, the Finback had rescued three naval avi- near Haha Jima. Aircraft in the area confirmed the loca- ators—a torpedo bomber crew—from the choppy central tion of the raft, and a plane circled overhead to mark the Pacific waters near the island of Tobiishi Bana during the location. The situation for the downed pilot looked grim; strikes on Iwo Jima. the raft was a mile and a half from shore, and the Japanese As dawn broke, the submarine’s radar picked up the in- were firing at it. coming wave of American planes heading towards Chichi Williams expressed his feelings about the stranded pilot’s Jima. situation in the war patrol report: “Spirits of all hands went A short time later, the Finback was contacted by two F6F to 300 feet.” This rescue would need to be creative because Hellcat fighters, their submarine combat air patrol escorts, the shore batteries threatened to hit the Finback on the sur- which submariners affectionately referred to as “chickens.” face if she tried to pick up the survivor there. The solution The Finback and the Hellcats were starting another day was to approach the raft submerged. But then how would of lifeguard duty to look for and rescue “zoomies,” the they get the aviator? submariners’ term for downed pilots. -

Closingin.Pdf

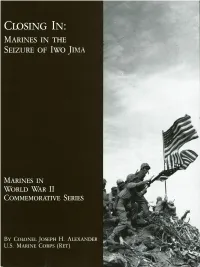

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

Teacher's Guide for Quiet Hero the Ira Hayes Story

Lee & Low Books Quiet Hero Teacher’s Guide p.1 Classroom Guide for QUIET HERO: THE IRA HAYES STORY by S.D. Nelson Reading Level *Reading Level: Grades 4 UP Interest Level: Grades 2-8 Guided Reading Level: P Lexile™ Measure: 930 *Reading level based on the Spache Readability Formula Themes Heroism, Patriotism, Personal Courage, Loyalty, Honor, World War II, Native American History National Standards SOCIAL STUDIES: Culture; Individual Development and Identity; Individuals, Groups, and Institutions LANGUAGE ARTS: Understanding the Human Experience; Multicultural Understanding Born on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona, Ira Hayes was a bashful boy who never wanted to be the center of attention. At the government-run boarding school he attended, he often felt lonely and out of place. When the United States entered World War II, Hayes joined the Marines to serve his country. He thrived at boot camp and finally felt as if he belonged. Hayes fought honorably on the Pacific front and in 1945 was sent with his battalion to Iwo Jima, a tiny island south of Japan. There he took part in the ferocious fighting to secure the island. On February 23, 1945, Hayes was one of six men who raised the American flag on the summit of Mount Suribachi at the far end of the island. A photographer for the Associated Press, Joe Rosenthal, caught the flag- raising with his camera. Rosenthal’s photo became an iconic image of American courage and is one of the best-known war pictures ever taken. The photograph also catapulted Ira Hayes into the role of national hero, a position he felt he hadn’t earned. -

World at War and the Fires Between War Again?

World at War and the Fires Between War Again? The Rhodes Colossus.© The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group / ImageQuest 2016 These days there are very few colonies in the traditional sense. But it wasn't that long ago that colonialism was very common around the world. How do you think your life would be different if this were still the case? If World War II hadn’t occurred, this might be a reality. As you've already learned, in the late 19th century, European nations competed with one another to grab the largest and richest regions of the globe to gain wealth and power. The imperialists swept over Asia and Africa, with Italy and France taking control of large parts of North Africa. Imperialism pitted European countries against each other as potential competitors or threats. Germany was a late participant in the imperial game, so it pursued colonies with a single-minded intensity. To further its imperial goals, Germany also began to build up its military in order to defend its colonies and itself against other European nations. German militarization alarmed other European nations, which then began to build up their militaries, too. Defensive alliances among nations were forged. These complex interdependencies were one factor that led to World War I. What Led to WWII?—Text Version Review the map description and the descriptions of the makeup of the world at the start of World War II (WWII). Map Description: There is a map of the world. There are a number of countries shaded four different colors: dark green, light green, blue, and gray. -

World War II

World War II 1. What position did George Marshall hold during World War II? A. Commanding General of the Pacific B. Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army C. Army Field Marshall of Bataan D. Supreme Officer of European Operations 2. Which of the following best explains why President Harry S. Truman decided to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II? A. He wanted the war to last as long as possible. B. He wanted to wait for the USSR to join the war. C. He wanted Germany to surrender unconditionally. D. He wanted to avoid an American invasion of Japan. 3. What impact did the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor have on World War II? A. Italy surrendered and united with the Allies. B. The Pacific Charter was organized against Japan. C. Japan surrendered to the Allies the following day. D. It pulled the United States into World War II. 4. The picture above is an iconic image from World War II and symbolizes which of the following? A. the women who ferried supplies into combat areas during the war B. the millions of women who joined the workforce in heavy industry C. the important work done by Red Cross nurses during World War II D. the women who joined the armed forces in combat roles Battle of the Bulge The Battle of the Bulge, initially known as the Ardennes Offensive, began on December 16, 1944. Hitler believed that the coalition between Britain, France, and the United States in the western region of Europe was not very powerful and that a major defeat by the Germans would break up the Allied forces. -

Pacific 1939-1945: Iwo Jima

PACIFIC 1939-1945: IWO JIMA IWO JIMA: TASK INSTRUCTIONS The key question: Why was the battle for Iwo Jima so important to America? Your task: You work as a tour guide in the park where the US Marine Corps Memorial is situated. Decide how you would explain the memorial and its history to visitors. Click on the starter source for more details then open the source box. Download a PDF of this whole investigation. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 PACIFIC 1939-1945: IWO JIMA WHY WAS THE BATTLE FOR IWO JIMA SO IMPORTANT TO AMERICA? For many Americans, Joe Rosenthal’s photograph showing the raising of the American flag on the island of Iwo Jima is highly significant. There are several reasons for this: • It is such a powerful and dramatic image • It is a statement of loyalty to the US – after such a hard battle US troops still had the strength to raise the flag • The image, and the men in it, was used in a publicity campaign to get Americans to buy war bonds (funds for the war effort) – this made millions aware of the image and the story behind it • Each side in this battle fought bravely • It was the first time Allied forces landed on Japanese home territory (rather than lands Japan had invaded) Casualties in the battle were enormous, which may have contributed to the decision to use the Atom Bomb. Your task You work as a tour guide in the park where the US Marine Corps Memorial is situated. Decide how you would explain the memorial and its history to visitors.