Radical Vernaculars FINAL DRAFT with Figures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in the Modern World

Art in the Modern World A U G U S T I N E C O L L E G E Arnold SCHOENBERG in 1911 Gurre Lieder 190110 Arnold SCHOENBERG in 1911 Gurre Lieder Pierrot lunaire, opus 21 190110 1912 First Communion 1874 Pablo PICASSO Portrait of Dora Maar Portrait of Dora Maar 1939 | Pablo PICASSO 1942 | Pablo PICASSO Portrait of Dora Maar MAN RAY Compassion 1897 William BOUGUEREAU Mont Sainte-Victoire 1904 | Paul CEZANNE Mont Sainte-Victoire Poppy Field 1904 1873 Paul CEZANNE Claude MONET Lac d’Annecy 1896 | Paul CEZANNE Turning Road at Mont Geroult 1898 Paul CEZANNE CUBISM Houses at l’Estaque 1908 Georges BRAQUE Grandes baigneuses 1900-06 | Paul CEZANNE Les demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 Pablo PICASSO African mask The Portuguese 1911-12 Georges BRAQUE Fruit Dish and Glass 1912 Georges BRAQUE Woman with Guitar 1913 Georges BRAQUE Woman with Guitar 1913 Georges BRAQUE Blue Trees 1888 Paul GAUGUIN Absinthe Drinker 1902 | Pablo PICASSO The Ascetic 1903 Pablo PICASSO The Accordionist 1911 Pablo PICASSO Musical Instruments 1912 Pablo PICASSO Face 1928 lithograph Pablo PICASSO Fruit Dish 1908-09 Pablo PICASSO Still-life with Liqueur Bottle 1909 Pablo PICASSO Woman in an Armchair 1913 | Pablo PICASSO Figures on the Beach 1937 | Pablo PICASSO Study for Figures on the Beach 1937 | Pablo PICASSO Weeping Woman 1937 | Pablo PICASSO Guernica 1937 | Pablo PICASSO Guernica details Guernica detail The Seamstress 1909-10 Fernand LEGER The City 1919 | Fernand LEGER Propellers 1918 Fernand LEGER Three Women 1921 | Fernand LEGER Divers on a Yellow Background 1941 | Fernand LEGER FAUVISM Fruit and Cafetière 1899 | Henri MATISSE Male Model 1900 | Henri MATISSE Open Window 1905 Henri MATISSE Woman with a Hat 1905 Henri MATISSE Bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life) 1906 | Henri MATISSE Terrace, St. -

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT SEARCH AND RESCUE BY PHILIP GOUREVITCH On the evening of May 22, 1988, a hundred and ten Vietnamese men, women, and children huddled aboard a leaky forty-five-foot junk bound for Malaysia. For the price of an ounce of gold each—the traffickers’ fee for orchestrating the escape—they became boat people, joining the million or so others who had taken their chances on the South China Sea to flee Vietnam after the Communist takeover. No one knows how many of them died, but estimates rose as high as one in three. The group on the junk were told that their voyage would take four or five days, but on the third day the engine quit working. For the next two weeks, they drifted, while dozens of ships passed them by. They ran out of food and potable water, and some of them died. Then an American warship appeared, the U.S.S. Dubuque, under the command of Captain Alexander Balian, who stopped to inspect the boat and to give its occupants tinned meat, water, and a map. The rations didn’t last long. The nearest land was the Philippines, more than two hundred miles away, and it took eighteen days to get there. By then, only fifty-two of the boat people were left alive to tell how they had made it—by eating their dead shipmates. It was an extraordinary story, and it had an extraordinary consequence: Captain Balian, a much decorated Vietnam War veteran, was relieved of his command and court- martialled, for failing to offer adequate assistance to the passengers. -

Diplomarbeit Der Utopiediskurs in Der Amerikanischen, Postapokalyptischen Serie the Walking Dead

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Der Utopiediskurs in der amerikanischen, postapokalyptischen Serie The Walking Dead“ verfasst von Doris Kaminsky angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 313 333 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UniStG UF Geschichte, Sozialkunde und Politische Bildung UniStG UF Deutsch UniStG Betreut von: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Frank Stern Danksagung Zuerst möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meinem Betreuer Dr. Frank Stern bedanken, der mir auch in schwierigen Phasen aufmunternde Worte zugesprochen hat und mit zahlreichen Tipps und Anregungen immer an meiner Seite stand. Zudem will ich mich auch bei Herrn Professor Dr. Stefan Zahlmann M.A. bedanken, der durch seine anregenden Seminare meine Themenfindung maßgeblich beeinflusst hat. Großer Dank gebührt auch meinen Eltern, die immer an mich geglaubt haben und auch in dieser Phase meines Lebens mit tatkräftiger Unterstützung hinter mir standen. Außerdem möchte ich mich auch bei meinen Freunden bedanken, für die ich weniger Zeit hatte, die aber trotzdem zu jeder Zeit ein offenes Ohr für meine Probleme hatten. Ein besonderer Dank gilt auch meinem Freund Wasi und Wolf, die diese ganze Arbeit mit sehr viel Sorgfalt gelesen und korrigiert haben. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung........................................................................................................ 1 2. Utopie, Eutopie und Dystopie................................................................ 4 2.1 Definition und Merkmale der Utopie.............................................. 5 2.2 Vom Raum zur Zeit: eine kurze Geschichte der Utopie.................. 7 2.2 Die Utopie im Medium Film und Fernsehen................................... 9 3. „Zombie goes global“ – Der Zombieapokalypsefilm und der utopische Impuls.................... 11 3.1 Vom Horror zur Endzeit – Das Endzeitszenario und der Zombiefilm.................................... 12 3.1.1 Das Subgenre Endzeitfilm und die Abgrenzung vom Horrorgenre...... -

The Walking Dead

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1080950 Filing date: 09/10/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91217941 Party Plaintiff Robert Kirkman, LLC Correspondence JAMES D WEINBERGER Address FROSS ZELNICK LEHRMAN & ZISSU PC 151 WEST 42ND STREET, 17TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] 212-813-5900 Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name James D. Weinberger Filer's email [email protected] Signature /s/ James D. Weinberger Date 09/10/2020 Attachments F3676523.PDF(42071 bytes ) F3678658.PDF(2906955 bytes ) F3678659.PDF(5795279 bytes ) F3678660.PDF(4906991 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Cons. Opp. and Canc. Nos. 91217941 (parent), 91217992, 91218267, 91222005, Opposer, 91222719, 91227277, 91233571, 91233806, 91240356, 92068261 and 92068613 -against- PHILLIP THEODOROU and ANNA THEODOROU, Applicants. ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Opposer, -against- STEVEN THEODOROU and PHILLIP THEODOROU, Applicants. OPPOSER’S NOTICE OF RELIANCE ON INTERNET DOCUMENTS Opposer Robert Kirkman, LLC (“Opposer”) hereby makes of record and notifies Applicant- Registrant of its reliance on the following internet documents submitted pursuant to Rule 2.122(e) of the Trademark Rules of Practice, 37 C.F.R. § 2.122(e), TBMP § 704.08(b), and Fed. R. Evid. 401, and authenticated pursuant to Fed. -

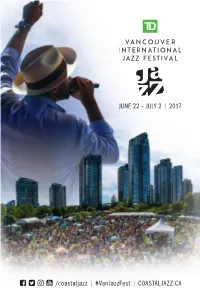

Jazz-Fest-2017-Program-Guide.Pdf

JUNE 22 – JULY 2 | 2017 /coastaljazz | #VanJazzFest | COASTALJAZZ.CA 20TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017 181 CHAN CENTRE PRESENTS SERIES The Blind Boys of Alabama with Ben Heppner I SEP 23 The Gloaming I OCT 15 Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland: Crosscurrents I OCT 28 Ruthie Foster, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Carrie Rodriguez I NOV 8 The Jazz Epistles: Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masekela I FEB 18 Lila Downs I MAR 10 Daymé Arocena and Roberto Fonseca I APR 15 Circa: Opus I APR 28 BEYOND WORDS SERIES Kate Evans: Threads I SEP 29 Tanya Tagaq and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory I MAR 16+17 SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE MAY 2 DAYMÉ AROCENA THE BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA HUGH MASEKELA TANYA TAGAQ chancentre.com Welcome to the 32nd Annual TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival TD is pleased to bring you the 2017 TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival, a widely loved and cherished world-class event celebrating talented and culturally diverse artists from Canada and around the world. In Vancouver, we share a love of music — it is a passion that brings us together and enriches our lives. Music is powerful. It can transport us to faraway places or trigger a pleasant memory. Music is also one of many ways that TD connects with customers and communities across the country. And what better way to come together than to celebrate music at several major music festivals from Victoria to Halifax. ousands of fans across British Columbia — including me — look forward to this event every year. I’m excited to take in the music by local and international talent and enjoy the great celebration this festival has to o er. -

UESDAT, AUGUST 81; 19431 L the Weather

<iA4« TUESDAT, AUGUST 81; 19431 _L The Weather . Uerage Daily CircuIatiM Foreeaot of I’. S. Weather Bureau Mrs. Charles Biraie of 73 Spruce Emergency Doctor^ [ to his family, I am sura they • the Month of August, IW* oy u street and her - daughters, Mrs. Pays Tribute would want to know wher^ he is Not nwM'h change In tempera A bout T ? Leonard Farrand and Miss Lor buried,” .To Begin Studies Nieb Johnson INCOME TAX SERVICE I ture tonight or Thursday morn raine Birnie have returned after Dr„ George Lundberg of the . 1,2 . 5 8 Manchester Medical Asidcla-s. Lieutenant Duffy who has been PrelVmlnary T «x tt«luraB ing. ' Mrs. Arthur Hanson of Oolway spending a few days in New York, on a number of bombing missions >leniberN4the Au«|It where they were guests at the tion will respond to emergency^ To His Buddy In So. Pacific for ludivtduals ^ itraet has ratumed aftar spandlng: calls tomorrow afternoon./ ' writes that each time he goes up Burrau of Clf^laU ^s \- a week Mt the shore cottage of Roosevelt Hotel. Their son and he writes Squat’s name on every Ara Duo September 15th. J____ Manchester— A City of Villafie Charm bar/aMae, Mrs. Roheet Coseo. at brother; Private Louis W. Birnie, bomb as a tribute to a great fight U. S. M. C,, left Saturday morn Lieiit. Elmer Duffys 111 Telephone Manchester 32081 Po^Mttock, Oroton. Mr. and Mrs. C. T^,-AIll..ion of er, and he adds that some of them lA>c(d Paramarine Noti PRICE THREE CENTS ing by plane from La Guardin' MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 1,1943 Fast Center street are spending Letter Home, Speak$ have hit their Urget squarely in (aassISed Advertlaing on Pago 14) Mias Ethel Ta3rIor of Madison Field to the. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“Music of Our Time” When I worked at Columbia Records during the second half of the 1960s, the company was run in an enlightened way by its imaginative president, Goddard Lieberson. Himself a composer and a friend to many writers, artists, and musicians, Lieberson believed that a major record company should devote some of its resources to projects that had cultural value even if they didn’t bring in big profits from the marketplace. During those years American society was in crisis and the Vietnam War was raging; musical tastes were changing fast. It was clear to executives who ran record companies that new “hits” appealing to young people were liable to break out from unknown sources—but no one knew in advance what they would be or where they would come from. Columbia, successful and prosperous, was making plenty of money thanks to its Broadway musical and popular music albums. Classical music sold pretty well also. The company could afford to take chances. In that environment, thanks to Lieberson and Masterworks chief John McClure, I was allowed to produce a few recordings of new works that were off the beaten track. John McClure and I came up with the phrase, “Music of Our Time.” The budgets had to be kept small, but that was not a great obstacle because the artists whom I knew and whose work I wanted to produce were used to operating with little money. We wanted to produce the best and most strongly innovative new work that we could find out about. Innovation in those days had partly to do with creative uses of electronics, which had recently begun changing music in ways that would have been unimaginable earlier, and partly with a questioning of basic assumptions. -

Sound Matters: Postcolonial Critique for a Viral Age

Philosophische Fakultät Lars Eckstein Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Suggested citation referring to the original publication: Atlantic studies 13 (2016) 4, pp. 445–456 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 ISSN (online) 1740-4649 ISBN (print) 1478-8810 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Philosophische Reihe ; 119 ISSN 1866-8380 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-98393 ATLANTIC STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 13, NO. 4, 445–456 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Lars Eckstein Department of English and American Studies, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This essay proposes a reorientation in postcolonial studies that takes Sound; M.I.A.; Galang; music; account of the transcultural realities of the viral twenty-first century. postcolonial critique; This reorientation entails close attention to actual performances, transculturality; pirate their specific medial embeddedness, and their entanglement in modernity; Great Britain; South Asian diaspora concrete formal or informal material conditions. It suggests that rather than a focus on print and writing favoured by theories in the wake of the linguistic turn, performed lyrics and sounds may be better suited to guide the conceptual work. Accordingly, the essay chooses a classic of early twentieth-century digital music – M.I.A.’s 2003/2005 single “Galang”–as its guiding example. It ultimately leads up to a reflection on what Ravi Sundaram coined as “pirate modernity,” which challenges us to rethink notions of artistic authorship and authority, hegemony and subversion, culture and theory in the postcolonial world of today. -

Counter-Tradition: Toward the Black Vanguard of Contemporary Brazil

10 Counter-Tradition: Toward the Black Vanguard of Contemporary Brazil GG Albuquerque In the 1930s, the first samba school, Deixa Falar, located in the Estácio de Sá neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, was experiencing a period of growth. More and more people were accompanying the carnival parade, singing and celebrating in the streets of the city. But this expansion brought an acoustic problem to the sambistas (samba players): amid that crowd, the people could not clearly understand the music that was being played and sung. In an attempt to solve this problem, the composer Alcebíades Barcelos, aka Bide, used his technical skills as a shoemaker and clothed a 20-kilogram butter can with a moistened cement paper bag, tying it to the can with wires and thumbtacks. The result was a brilliant creation: Bide had invented the surdo, a bass drum that not only solved the initial problem of acoustic demand from samba schools, but also revolutionized Brazilian popular music. Until that time, samba had a very different sound from what we now recognize as samba. A notorious example is Donga’s “Pelo Telefone” (1916). The music exhibited a slow swing influenced by rural sounds (like the maxixe) and European genres (like polka and Scottish), and was recognized as the first samba ever recorded. The polyrhythmic drums, the batucada that became the structural pillar of samba, would only flourish a little more than a decade later, precisely because of the experiments of Estácio de Sá’s musicians in the 1930s. Bide and other composers, such as Ismael Silva, Armando Marçal, Heitor dos Prazeres, Brancura, Baiano, Baiaco, and Getúlio Marinho, developed the sonic language of the urban samba in Rio de Janeiro, the samba de sambar:1 a new sonic configuration based on fast syncopated rhythms and simpler, more direct, and more effective harmonies to be sung in the streets during carnival. -

Domestic Terrorism in Africa

DOMESTIC TERRORISM IN AFRICA: DOMESTIC TERRORISM IN AFRICA: DEFINING, ADDRESSING AND UNDERSTANDING ITS IMPACT ON HUMAN SECURITY DEFINING, ADDRESSING AND UNDERSTANDING ITS IMPACT ON HUMAN SECURITY Terrorism Studies & Research Program ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court, VealVeale Street New Muckleneuk,, PrPretoria Tel: (27-12) 346 9500 Fax:Fa (27-12) 346 9570 E-mail: iss@[email protected] ISS AdAddis Ababa Offi ce FirsFirst Floor, Ki-Ab Building, Alexander Pushkin Street, Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa Tell:(: (251-1111)3) 37272-1154/5/6 Fax:(: (251-1111)3) 372 5954 E-mail: addisababa@is@ safrica.orgg ISS Cape Town Offi ce 67 Roeland Square, Drury Lane Gardens Cape Town 8001 South Africa TTel:(: (27-27 21) 46171 7211 Fax: (27-2121)4) 461 7213 E-mail: [email protected] ISS Nairobi Offi ce 5h5th Flloooor, LanddmarkPk Pllaza Argwings Kodhekek RRoad, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: (254 -20) 300 5726/8 FaxFax: (254-20) 271 2902 E-mail: [email protected] ISS Pretoria Offi ce Block C, Brooklyn Court, Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria Tel: (27-12) 346 9500 Fax: (27-12) 460 0998 Edited by Wafula Okumu and Anneli Botha E-mail: [email protected] Wafula Okumu and Anneli Botha www.issafrica.org 5 and 6 November 2007 This publication was made possible through funding provided by the ISBN 978-1-920114-80-0 Norwegian Government. In addition, general Institute funding is provided by the Governments of Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. 9 781920 114800 Terrorism Studies & Research Program As a leading African human security research institution, the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) works towards a stable and peaceful Africa characterised by sustainable development, human rights, the rule of law, democracy, collaborative security and gender mainstreaming. -

Billboard 1967-11-04

EijilNOVEMBER 4, 1967 SEVENTY -THIRD YEAR 75 CENTS The International Music -Record Newsweekly Labels Hold Boston Capitol to Back Labels Int'l Pop Fest Koppelman & Rubin Talent) Parties in Of By ELIOT TIEGEL Planned for N.Y. NEW YORK - Capitol Rec- Koppelman, co -owner of the ords will finance and distribute two -year -old independent disk All -Out Artist Hunt a series of pop labels formed producing firm /music publish- By HANK FOX by Charles Koppelman and Don ing combine, said Capitol's in- To Help Charity BOSTON - "Stand up straight -talent scouts Rubin. The affiliation marks vestment in the first of his new are watching you" is the advice circulating the record manufacturer's sec- labels, The Hot Biscuit Disc By CLAUDE HALL through this town and Cambridge. Record com- ond such deal with an out- Co., was over $1 million. Hot moving side interest. The Beach Boys' Biscuit's debut single, sched- NEW YORK -An International Pop Music panies and independent producers are 40 of the world's into the region, furiously signing local talent for Brother Records was launched uled for release in two weeks, Festival, featuring more than top artists and groups, is being planned for late a major onslaught of releases by Boston -based several months ago from the introduces a new New York Coast. (Continued on page 10) June next year in Central Park here. Sid Bern- groups due to hit the market in January. organizing Boston and Cambridge groups are stein, the promoter- manager who is At least six it more than scheduled for release in January, and the Festival, believes will draw already for a three -day event.