'Hello/Goodbye'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

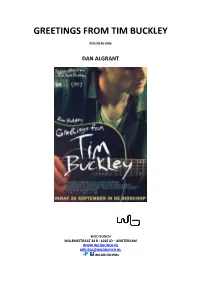

Greetings from Tim Buckley

GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY EEN FILM VAN DAN ALGRANT WILD BUNCH WILLEMSSTRAAT 24 B - 1015 JD – AMSTERDAM WWW.WILDBUNCH.NL [email protected] WILDBUNCHblx GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT PROJECT SUMMARY EEN PRODUCTIE VAN FROM A TO Z PRODUCTIONS, SMUGGLER FILMS TAAL ENGELS LENGTE 99 MINUTEN GENRE DRAMA LAND VAN HERKOMST USA FILMMAKER DAN ALGRANT HOOFDROLLEN PENN BADGLEY, IMOGEN POOTS RELEASEDATUM 26 SEPTEMBER 2013 KIJKWIJZER SYNOPSIS In 1991 repeteert een jonge Jeff Buckley voor zijn optreden tijdens een tribute show ter ere van zijn vader, wijlen volkszanger Tim Buckley. Terwijl hij worstelt met de erfenis van een man die hij nauwelijks kende, vormt Jeff een vriendschap met een mysterieuze jonge vrouw die bij de show werkt en begint hij de potentie van zijn eigen muzikale stem te ontdekken. CAST JEFF PENN BADGLEY ALLIE IMOGEN POOTS TIM BEN ROSENFIELD GARY FRANK WOOD JEN JENNIFER TURNER CAROL KATE NASH JANE ISABELLE MCNALLY LEE WILLIAM SADLER HAL NORBERT LEO BUTZ YOUNG LINDA JADYN STRAND RICHARD FRANK BELLO JANINE NICHOLS JESSICA STONE YOUNG LEE TYLER GILHAM SIRENS KEMP AND EDEN C.H. DAVID SCHNIRMAN CARTER STEPHEN TYRONE WILLIAMS MILOS CHRISTOPH MANUEL FRANK DAVID LIPMAN GARY LUCAS GARY LUCAS CREW DIRECTOR DAN ALGRANT SCREENWRITER DAN ALGRANT DAVID BRENDEL EMMA SHEANSHANG CINEMATOGRAPHER ANDRIJ PAREKH EDITOR BILL PANKOW CASTING AVY KAUFMAN PRODUCTION DESIGN JOHN PAINO COSTUME DESIGN DAVID C. ROBINSON ORIGINAL MUSIC GARY LUCAS GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Before GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY, I had made two short films about my father. When I was 21, I made the first film about how much I hated him when he left my mother. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Tim Buckley Il Navigatore Delle Stelle

Tim Buckley Il navigatore delle stelle originali scritte dall'ex compagno di scuola - aspirante poeta - Larry Beckett. Abbandonati definitivamente gli studi universitari trova il suo ambiente ideale al losangelino Troubadour. Qui fa amicizia con un chitarrista di squisita tecnica esecutiva, Lee Underwood, e soprattutto è notato da un certo Herb Cohen, astutissimo manager di Frank Zappa e Captain Beefheart, che lo presenta al boss dell'Elektra Jac Holzman. Sottoscritto un contratto con quell'etichetta, in soli tre giorni incide negli studi Sunset Sound il disco di debutto, intitolato semplicemente Tim Buckley, avvalendosi del prezioso supporto di ottimi musicisti. Oltre agli amici Lee Underwood e Jim Fielder (basso), sono della partita Billy Mundi (batteria e percussioni), la stella Van Dyke Parks (piano, celeste, harpsichord) e Jack Nitzsche artefice dei sontuosi arrangiamenti. L'album, in vendita durante le festività natalizie del 1966, inanella una lunga serie di classiche ballate «Lo splendore del sole ricorda i cieli La sua America gli regalerà pochi folk ispirate direttamente a Fred successi, mentre l'Europa lo scoprirà Neil, Tim Hardin e soprattutto a Bob della realtà/Pensavi di stare volando molto tardi con la sola eccezione Dylan (Aren't You The Girl, Song ma hai dovuto aprire gli occhi» della Francia, dove una élite di For Janie, Understand Your Man), Tim Buckley da Pleasant Street persone lo elegge come il più anche se Tim è in grado di grande innovatore della musica a apportare originali e minuziose stelle e strisce dopo Bob Dylan. variazioni armoniche (I Can't See Folksinger di enorme forza e dolcezza, Timothy Charles Buckley III nasce a You). -

Publication (11.32

Music 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights ................................................................................ 1 Classical............................................................................. 11 Jazz, Pop, Folk & Rock ...................................................16 Film & Theatre ............................................................24 Resources for Performers Conductors ...............................................28 Vocalists .....................................................31 Instrumentalists .........................................34 Education Resources ........................................37 Ethnomusicology ...............................................40 Classic Books .......................................................42 Index ...................................................................47 Ordering Information ..............................................48 e Are Available from Ebooks Rowman & Littlefield is proud to provide most of its frontlist and selected backlist—a stable of over 10,000 titles—as ebooks, through its partnership with over fifty vendors, including • Amazon Kindle • Ingram Digital Retail • Amazon Look Inside Books The Book • Kobo • Apple iBooks • MyiLibrary • Barnes & Noble Nook • NetLibrary • Barnes & Noble See Inside • OverDrive • Baker & Taylor Blio • Questia • Chegg • Scribd • Ebooks Ltd. • Shortcovers • Ebrary • Skiff • Folletts/CafeScribe • Sony Reader • Google BookSearch • Zinio • Google Editions NEW! Purchase individual ebooks directly from our website. -

Warner/Reprise Loss Leaders Booklet

THE WARNER BROS. LOSS LEADERS SERIES (1969-1980) Depending On How You Count Them, 34 Essential Various Artist Collections From Another Time We figured it was about time to pull together all of the incredible Warner Bros. Loss Leaders releases dating back to 1969 (and even a little earlier). For those who lived through the era, Warner Bros. Records was winning the sales of an entire generation by signing and supporting some of music’s most uniquely groundbreaking recording artists… during music’s most uniquely groundbreak- ing time. With an appealingly irreverent style (“targeted youth marketing,” it would be called today), WB was making lifelong fans of the kids who entered into the label’s vast catalog of art- ists via the Loss Leaders series—advertised on inner sleeves & brochures, and offering generous selections priced at $1 per LP, $2 for doubles and $3 for their sole 3-LP release, Looney Tunes And Merrie Melodies. And that was including postage. Yes… those were the days, but back then there were very few ways, outside of cut-out bins or a five-finger discount, to score bulk music as cheaply. Warners unashamedly admitted that their inten- tions were to sell more records, by introducing listeners to music they weren’t hearing on their radios, or finding in many of their (still weakly distributed) record stores. And it seemed to work… because the series continued until 1980, and the program issued approximately 34 titles, by our questionable count (detailed in later posts). But, the oldsters among us all fondly remember the multi-paged, gatefold sleeves and inviting artwork/packaging that beckoned from the inner sleeves of our favorite albums, not to mention the assorted rarities, b-sides and oddities that dotted many of the releases. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Tim Buckley 101: New DVD Inspires Comprehensive Look at Jeff'

Tim Buckley 101: New DVD Inspires Comprehensive Look at Jeff’s Dad http://www.nadamucho.com/columns/rock_101/tim_buckley_101_new... Ask us about our world famous peach cobbler. Features Live Columns Interviews Reviews Forum Home search... About Nada Write Us Sitemap Home Columns Tim Buckley 101: New DVD Inspires Comprehensive Look at Jeff’s Dad Top Articles Tim Buckley 101: New DVD Inspires Comprehensive Look at Jeff’s Dad Odes to Onanism - Best By Christian Klepac Masturbation Songs Friday, 20 July 2007 Hypatia Lake - Your Universe, Your Mind Sooner or later, every music fan must reckon with the The Glasses: Ready to be Buckleys. Recognized on the Street I'm Right, You're Wrong - Sex Advice for the Confused Father Tim and son Jeff, the Bruce and Brandon Lee of the Lawyers Guns & Money - music world, were geniuses with golden vocal chords and Zevon's Ghost weirdly parallel lives. Classic Nada: Lawyers, Guns and Money - Daniel Faulkner The two spent time together only briefly, when Jeff was too 2005 Favorites - Music Editor's young to remember, but they both eschewed compromise Picks while pursuing their challenging eclectic musical visions, and Ramble On - October 2003 both their careers were cut tragically short by their untimely Bumbershoot 2003 Recap deaths, Tim at 28 and Jeff at 30. Goin' Back to Tucson - September 2003 Ramble On - May 2003 Jeff, of course, shot to stardom with the release of his 1994 Classic Nada - Young debut Grace, one of the best records to come out of the 90s, Poisoner's Handbook and one that still appears regularly near the top of music I'm Right, You're Wrong magazine "best of" lists. -

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to The

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to the CD-2 “No Direction Home”, Michael Bloomfield plays the guitar intro and a solo later and Dylan plays the opening solo (his one and only recorded electric solo?) 1. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.24) (take 1) slow 2. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Bloomfield solo 3. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Dylan & Bloomfield guitar solo 4. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.23) extra verse On track (2) there is very fine playing from MB and no guitar solo from Uncle Bob, but a harmonica solo. 1966 3 – LP-2 “BLONDE ON BLONDE” COLUMBIA 1966? 3 – EP “BOB DYLAN” CBS EP 6345 (Portugal) 1987? 3 – CD “BLONDE ON BLONDE” CBS CDCBS 66012 (UK) 546 1992? 3 – CD “BOB DYLAN’S GREATEST HITS 2” COLUMBIA 471243 2 (AUT) 109 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 - COLUMBIA C2K 93937 (US) 529 Alternate take 1 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 – COL 520358-2 (UK) 562 Alternate take 1 ***** Febr. 4.-11, 1966 – The Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Whiskey a Go Go, LA, CA Feb. 25, 1966 – Butterfield Blues Band -- Fillmore ***** THE CHICAGO LOOP 1966 Prod. Bob Crewe and Al Kasha 1,3,4 - Al Kasha 2 Judy Novy, vocals, percussion - Bob Slawson, vocals, rhythm guitar - Barry Goldberg, organ, piano - Carmine Riale, bass - John Siomos, drums - Michael Bloomfield, guitar 1 - John Savanno, guitar, 2-4 1. "(When She Wants Good Lovin') She Comes To Me" (2.49) 1a. -

Track Artist Album Format Ref # Titirangi Folk Music Club

Titirangi Folk Music Club - Library Tracks List Track Artist Album Format Ref # 12 Bar Blues Bron Ault-Connell Bron Ault-Connell CD B-CD00126 12 Gates Bruce Hall Sounds Of Titirangi 1982 - 1995 CD V-CD00031 The 12th Day of July Various Artists Loyalist Prisoners Aid - UDA Vinyl LP V-VB00090 1-800-799-7233 [Live] Saffire - the Uppity Blues Women Live & Uppity CD S-CD00074 1891 Bushwackers Faces in the Street Vinyl LP B-VN00057 1913 Massacre Ramblin' Jack Elliot The Essential Ramblin' Jack Elliot Vinyl LP R-VA00014 1913 Massacre Ramblin' Jack Elliot The Greatest Songs of Woodie Guthrie Vinyl LP X W-VA00018 The 23rd of June Danny Spooner & Gordon McIntyre Revived & Relieved! Vinyl LP D-VN00020 The 23rd Of June the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem Hearty And Hellish Vinyl LP C-VB00020 3 Morris Tunes - Wheatley Processional / Twenty-ninth of May George Deacon & Marion Ross Sweet William's Ghost Vinyl LP G-VB00033 3/4 and 6/8 Time Pete Seeger How to play the Old Time Banjo Vinyl LP P-VA00009 30 Years Ago Various Artists & Lindsey Baker Hamilton Acoustic Music Club CD H-CD00067 35 Below Lorina Harding Lucky Damn Woman CD L-CD00004 4th July James RAy James RAy - Live At TFMC - October 2003 CD - TFMC J-CN00197 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary In Concert Vinyl LP X P-VA00145 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary Best of Peter, Paul & Mary: Ten Years Together Vinyl LP P-VA00101 500 Miles The Kingston Trio Greatest Hits Vinyl LP K-VA00124 70 Miles Pete Seeger God Bless the Grass Vinyl LP S-VA00042 900 Miles Cisco Houston The Greatest Songs of Woodie Guthrie Vinyl LP -

When She's Gone

When She’s Gone Steven Erikson © Steven Erikson 2004 The game got in our blood when the Selkirk Settlers first showed up at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Not hard to figure out why. They were farmers one and all and given land along the rivers, each allotment the precise dimensions of a hockey rink. Come winter the whole world froze up and there was nothing to do but skate and whack at frozen rubber discs with hickory sticks. Those first leagues were vicious. There were two major ones, the Northwest League and the Hudson's Bay League. Serious rivals and it all came to a head when Louis Riel, left-wing for the Voyageurs, jumped leagues and signed with the Métis Traders right there at the corner of Portage and Main, posing with a buffalo hide signing bonus. The whole territory went up in flames–the Riel Rebellion–culminating in the slaughter of nineteen Selkirk fans. Redcoats came from the east and refereed the mob that strung Riel up and hung him until dead. The Northwest League got merged into the Hudson's Bay League shortly afterward and a troubled peace came to the land. It was the first slapshot fired in anger, but it wouldn't be the last. The game We sold our soul. No point in complaining, no point in blaming anyone else, not the Yanks, not anyone else. We've done it ourselves and if you were a Yank you'd be saying the same thing. If your country was Italy, France or Belgium, if the city you called home was in England or Scotland or Wales, you're saying the same thing I'm saying right now, at least you'd be if you were thinking about what I'm thinking about. -

Tim Buckley Starsailor Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tim Buckley Starsailor mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Starsailor Country: US Released: 1970 Style: Folk Rock, Psychedelic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1617 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1178 mb WMA version RAR size: 1579 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 749 Other Formats: DTS VQF MP2 MP4 ASF AAC MIDI Tracklist A1 Come Here Woman 4:09 A2 I Woke Up 4:02 A3 Monterey 4:30 A4 Moulin Rouge 1:57 A5 Song To The Siren 3:20 B1 Jungle Fire 4:42 B2 Starsailor 4:36 B3 The Healing Festival 3:16 B4 Down By The Borderline 5:22 Companies, etc. Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Santa Maria Credits Art Direction, Photography By – Ed Trasher* Double Bass [String Bass], Electric Bass – John Balkin Electric Guitar, Electric Piano, Organ [Pipe] – Lee Underwood Engineer – Stan Agol Executive-Producer – Herb Cohen Flute [Alto], Tenor Saxophone – Bunk Gardner Timpani, Performer [Traps] – Maury Baker Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Buzz Gardner Vocals, Producer, Written-By, Twelve-String Guitar – Tim Buckley Written-By – John Balkin (tracks: B2), Larry Beckett (tracks: A2 To A4, B2) Notes Release has Straight and WB logos in the lower right corner of front cover. Label is red and says, "Straight Records, a division of Bizarre Inc., 5455 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1700, Los Angeles, 90036" Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (A-Side Etched): S I WS 1881 A 39774-1B A3 Matrix / Runout (B-Side Etched): WS 1881 39775-1 1A 1 A 2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Straight, Tim Starsailor (LP, WS 1881 Warner Bros.