Working Paper 66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perceptions of Stakeholders on Post-War Reconstruction of Secondary Education in Kailahun District, Sierra Leone

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications ISSN (Online): 2581-6187 The Perceptions of Stakeholders on Post-War Reconstruction of Secondary Education in Kailahun District, Sierra Leone Yankuba Felix Moigua, Martha Fanta Mansaray Eastern Polytechnic, Kenema, Sierra Leone Abstract— The study investigated the perceptions of stakeholders on institutions to turn to. It is not surprising that literacy levels the problems and solutions of post war reconstruction of formal remained low due to the country‟s educational system and that secondary education in kailahun district which is located in the fewer than 15 percent of children aged between 5 .11 attended eastern province of sierra Leone, and is comprised of fourteen [14] schools and only 5 percent of children between 12 and 16 chiefdoms. The target group comprised of Inspectors/ Supervisors of years were in secondary schools. the ministry of Education, Science and Technology in kailahun district, NACSA, UNICEF,IRC,NRA, Principals, teachers, pupils, With the advent of the war, substantial portion of the community teachers associations of secondary schools and missions/ population displaced by the war were either in refugee camps proprietors in partnership management of secondary schools in the in Guinea or in Freetown and other bigger towns, the impact kailahun district. The study sample comprised of 97 respondents. The of the war on schooling and literacy level in Sierra Leone was study essentially involved the identification and description of devastating. Majority of the teachers were forced to flee to the stakeholders perceptions of problems and solutions in the postwar capital or out of the country and a lot of schools were either reconstruction of formal secondary education in Kailahun District in totally destroyed or damaged. -

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project, Search For

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project Search for Common Ground Background Over the next three-year period, Sierra Leone must capitalize on the opportunities provided by the end of the civil conflict to ensure a peaceful transition into a long-term development phase. These opportunities include: • the discourse of public participation and dialogue • tolerance for openness and freedom of the press • implementation of a decentralization policy and structural reforms. Media tolerance and diversification is central to a wider and broader range of available public information. A viable and functioning public information network supports deeper analysis on issues and the mobilization of the population for engagement in governance processes, including local and national elections, anti-corruption initiatives, and budgetary monitoring, among others. Search for Common Ground in Sierra Leone (SFCG) with the support of the United States Agency for International Development through cooperative agreement 636-A-00-05-00040 is supporting these transformation processes over the next three to five years. Capitalizing on new entry points created by governance reform and decentralization, SFCG, using its trusted media tools integrated with community outreach, will support the creation of demand for good governance and accountable leadership through participation, engagement and good citizenship. SFCG’s overarching goal for its democracy and governance project is to: Strengthen democratic governance in the districts of Kono, Kailahun, and Koinadugu, and Tongo Fields in Sierra Leone, which supports Special Objective #2 (SO2) under USAID/Sierra Leone’s Transition Strategy Phase 2, (FY 2004-2006). SFCG’s program objective is to: Stimulate an active citizenry. This supports Intermediate Result (IR) 2.2: “Citizens, local government, and CSOs better informed on democratic governance” of SO2. -

Reference Map of Kailahun, Eastern Province, Sierra Leone

MA002_Kailahun, Eastern Province Biama Gbogboragfeh Sawulla N ' Masundu Gbongbokoro Nongoua 0 3 ° 8 Kanekor Mak o na Tankoro Soa Nimikoro Koindu Mendekoma Nimiyama Gbane Kono Gandorhun GUINEA Reference map Tokpombu Kissi Gorama Kama of Foinba Kono Moimandu Kissi Gandohun li Dia Kangama Penguia Me Kailahun, Eastern Belebu Tolobu Teng Province, Malema Jerihun Moa Kangama Mano Sierra Leone Jerihun Saabendu Bandajuma Kéléma Baiama Sandialu Yawei GUINEA Kangahun Petema Kailahun Buedu Baoma Kissi Buobobu Woroma Tongi NORTHERN Dagbahun Sile Balahun Dodo Keya Malegohun Fobu Freetown Tongo Laoma Bandajuma Kpeje EASTERN West Giehun Talia Nyandehun Lalehun Lower Mende Luawa Panguma Bambara SOUTHERN Giehun Woa Giema Manowa Manowa Junction LIBERIA Dodo Kpeje Bongre e al Kenema M Foindu Belebu Kailahun Settlement Borders Lelehun Bendu Pendembu Capital National EASTERN Upper Bambara Province City un Gbolabu goh Mandulawahun Nia Town District Lago a auw Mano Levuma M village Chiefdom Baima Junction Vaahun Njaluahun Taninahun Bomaru Physical N Benduma Ma ° hi 8 Segbwema mb Komende Daru Mobai Baiwala e Lake Coastline Luyama Nongowa Mandu LIBERIA River Bombohun Transport Railway Jomu Gandohun o Dea Hangha Airport Roads Goma Nekabu Nyandehun ⛡ Port Primary Tikonko Gbaru Secondary Geblama Tertiary Jojoima Jawie 0 2 4 6 8 10 km Tokpombu Gofor Dama Data sources OpenStreetMap, Steward Project, COD-FOD Registry, Logistics Cluster La Malema Mo o gula rr M a Created 21 Oct 2014 / 11:00 UTC±00:00 m a w Map Document MA003_Reference_District a Projection / Datum WGS 1984 UTM Zone 29N Glide Number EP-2014-000039-SLE Joru Gaura Produced by MapAction Supported by www.mapaction.org [email protected] The depiction and use of boundaries, names and associated data shown Nomo here do not imply endorsement or Tunkia ´ acceptance by MapAction. -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

Produce Marketing Board

PUBLIC NOTICE The Public is hereby informed that on the 20tn-day of June 20'13, the Parliament of the Republic of Sierra Leone passed into law the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Act (Repeal) Act, 2013 ; and whereas Section 1 Sub section 2 of the said Act dissolved the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Board (SLPMB) and vested the properties and assets of the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Board (SLPMB) in the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Company (SLPMC) as listed in the Government of Sierra Leone Gazette Vol Cxliv No. 53 of Thursday 1Otn October 2013 (Notice No. 213). ln this regard, the National Commission for Privatisation (NCP) in collaboration with the Caretaker Team, have on Wednesday 30tn October, 20'13 handed over these assets as described in the Gazette public notice no,213 to the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Company (SLPMC) together with all lease agreements. Consequently, the public is hereby informed that the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Company (SLPMC) is currently embarking on a nationwide identification and possession of all assets and properties including plantations belonging to the former SLPMB and the Company is therefore requesting individuals or organizations occupying any of the said assets or properties to contact the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Company at No. 59A Wellington Street, Freetown with immediate effect, Signedffi* Henry iamna Kamara Managing Director SLPMC Wbe bterre lLtsttt @ilj$te lP rrb ti gb e[ trp Autltor ity Vol. CXLIV THUnsoeY, 10rs Ocronrn, 2013 No. 53 CONTE NTS G. N. PaoB G. N. Pece 2lL Public Service Notices 469-470 MINISTRY OF TRADE AI\ID INDUSTRY zlg List of Properties formally belonglng to the Sierra I 86- lrone Produce Marketing Board. -

Land Border Permeability Study

MONITORING, RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT NATIONAL REVENUE AUTHORITY 19 WELLINGTON STREET, FREETOWN. SEPTEMBER, 2006 Table of Content LIST OF TABLES…………………………………………………………………………...…...I ACKNOWLEDGEMENT…………………………………….…………………………….….III ACRONYMS……………………………………………………………………………….…...IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY….………………….…………………………..…………………...V 1.0 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………. ............................... 1 1.1 JUSTIFICATION OF THE STUDY ................................................................................ 1 1.1.1 Analyzing the focus and findings of the ONS Assessment ................................................................... 2 1.1.2 Limitations of the ONS Study, and the Relevance of the MRD Land Border Permeability Study ............ 3 1.2 OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 OUTPUT/DELIVERABLES .................................................................................................. 5 1.4 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................. 5 1.4.1 Sample Selection ........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4.2 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4.3 Data Analysis ............................................................................................................................................ -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE KAILAHUN DISTRICT ATLAS CHIEFDOMS: DIA P.2 JAWIE P.3 KISSI KAMA P.4 KISSI TENG P.5 KISSI TONGI P.6 LUAWA P.7 MALEMA P.8 MANDU P.9 NJALUAHUN P.10 PEHE BOGRE P.11 PEJE WEST P.12 PENGUIA P.13 UPPER BAMBARA P.14 YAWEI P.15 DIA CHIEFDOM 10°43'0"W 10°42'0"W 10°41'0"W 10°40'0"W 10°39'0"W 10°38'0"W 10°37'0"W 10°36'0"W 10°35'0"W 10°34'0"W Baoma Sembehun 8°4'0"N 8°4'0"N Manoworo Gbolabu Manoworo Kangama Bombohun Jawu Kponporu LUAWA Naiagolehun Blama 8°3'0"N Wunde 8°3'0"N UPPER BAMBARA Gondama Siama Salon Falaba 8°2'0"N 8°2'0"N Fumbala Tambiama Kpeyama Poruma 8°1'0"N 8°1'0"N Bomaru Pewama Jopowahun Kotuma Sakiema 8°0'0"N 8°0'0"N Dablama Pewama Baiwala Bohekema Malema Kangama 7°59'0"N 7°59'0"N Kpeima MANDU Grima Sipayema Polubu Gbalahun 7°58'0"N Dodo 7°58'0"N BogemaDIA Grima Kambema Maka Go Bogema Wumoima LIBERIA 7°57'0"N 7°57'0"N Njewoma Gohun Senga Kanga 7°56'0"N 7°56'0"N Nagbena Baoma 7°55'0"N Nalagolehun 7°55'0"N Tomiyama Bahama 7°54'0"N 7°54'0"N Takpoima MALEMA 7°53'0"N 7°53'0"N Bandajuma Gomsua 10°43'0"W 10°42'0"W 10°41'0"W 10°40'0"W 10°39'0"W 10°38'0"W 10°37'0"W 10°36'0"W 10°35'0"W 10°34'0"W GUINEA Kono GUINEA Town Sources: SIERRA Roads : OSM Kenema Village LEONE Places : OSM, GeoNames, MSF Kailahun Chiefdoms Health post, offices, bridges : MSF Admin borders : COD-FOD LIBERIA Road Document name: SLE_BM_KAILAHUN_A3 Date: 08/09/2014 LIBERIA Realised by GIS Unit Track 0 0.5 1 2 3 4 I5mpression: ISO A3 km JAWIE CHIEFDOM 11°2'0"W 11°1'0"W 11°0'0"W 10°59'0"W 10°58'0"W 10°57'0"W 10°56'0"W 10°55'0"W 10°54'0"W 10°53'0"W 10°52'0"W 10°51'0"W -

Taylor Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR MONDAY, 19 APRIL 2010 9.03 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Julia Sebutinde, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Teresa Doherty Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr Artur Appazov For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Ms Zainab Fofanah For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Nicholas Koumjian Mr Mohamed A Bangura Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Terry Munyard Ms Logan Hambrick CHARLES TAYLOR Page 39253 19 APRIL 2010 OPEN SESSION 1 Monday, 19 April 2010 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.03 a.m.] 08:58:06 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We will take appearances 6 first, please. 7 MR KOUMJIAN: Good morning, Madam President. Good morning, 8 your Honours, counsel opposite. For the Prosecution this 9 morning, Brenda J Hollis, Mohamed A Bangura, Maja Dimitrova and 09:03:32 10 myself, Nicholas Koumjian. 11 MR GRIFFITHS: Good morning, Madam President, your Honours, 12 counsel opposite. For the Defence today myself, Courtenay 13 Griffiths, with me Ms Logan Hambrick. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE: Yes, good morning, Mr Fayia. 09:03:50 15 THE WITNESS: Good morning, your Honour. 16 PRESIDING JUDGE: This morning you continue your testimony 17 with questions from the Prosecution. I just remind you of your 18 oath to tell the truth. Thank you. 19 Mr Koumjian, please proceed. 09:04:07 20 WITNESS: DCT-306 [On former oath] 21 CROSS-EXAMINATION BY MR KOUMJIAN: 22 Q. -

2006 Report on Electoral Constituency

August 2006 Preface This part of the report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each approved constituency. It comprises the chiefdoms, streets and other prominent features defining constituency boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved constituencies. Ms. Christiana A. M. Thorpe (Dr.) Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chairperson. I Table of Contents Page A. Eastern Region…………………..……………………1 1. Kailahun District ……………………………………1 2. Kenema District………………………..……………5 3. Kono District……………………….………………14 B. Northern Region………………………..……………19 1. Bombali District………………….………..………19 2. Kambia District………………………..…..………25 3. Koinadugu District………………………….……31 4. Port Loko District……………………….…………34 5. Tonkolili District……………………………………43 C. Southern District……………………………………47 1. Bo District…………………………..………………47 2. Bonthe District………………………………………54 3. Moyamba District……………….…………………56 4. Pujehun District……………………………………60 D. Western Region………………………….……………64 1. Western Rural …………………….…………….....64 2. Western Urban ………………………………………81 II EASTERN REGION KAILAHUN DISTRICT (01) DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCIES Name & Code Description of Constituency Kailahun District This constituency comprises of part of Luawa chiefdom with the Constituency 1 following sections: Baoma, Gbela, Luawa Foguiya, ManoSewallu, Mofindo, and Upper Kpombali. (NEC Const. 001) The constituency boundary starts along the Guinea/Sierra Leone international boundary northeast where the chiefdom boundaries of Kissi Kama and Luawa meet. It follows the Kissi Kama Luawa chiefdom boundary north and generally southeast to the meeting point of Kissi Kama, Luawa and Kissi Tongi chiefdoms. It continues along the Luawa/Kissi Tongi boundary south, east then south to meet the Guinea boundary on the southeastern boundary of Upper Kpombali section in Luawa chiefdom. It continues west wards along the international boundary to the southern boundary of Upper Kpombali section. -

Evaluation of DEC Ebola Response Programme

Final Report: Evaluation of DEC Ebola Response Program Phase 1 and 2 Submitted by: Hindowa Batilo Momoh-Lead Consultant; Dr. Fallah Lamin and Mr. Ibrahim Samai-Associate Consultants November 2016 DEC Emergency Response Program Implemented by CAFOD, Caritas, Street Child and Troacaire in Sierra Leone Table of Content LIST OF ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE EVALUATION .................................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 METHODS AND PROCESS............................................................................................................................................ 9 1.5 LIMITATION TO THE EVALUATION: ............................................................................................................................. -

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (Pdes)

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND EVALUATION SERVICE (PDES) A catalyst and a bridge An evaluation of UNHCR‟s community empowerment projects in Sierra Leone Claudena M. Skran PDES/2012/01 Independent consultant January 2012 Policy Development and Evaluation Service UNHCR‟s Policy Development and Evaluation Service (PDES) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. PDES also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR‟s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization‟s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other persons of concern to the Office. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8433 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org Printed by UNHCR All PDES evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting PDES. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in PDES publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

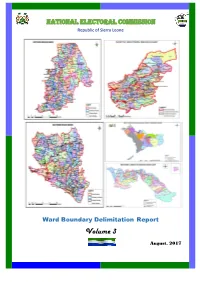

2017 Ward Description, Maps and Population

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Republic of Sierra Leone Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume 3 August, 2017 Foreword The National Electoral Commission (NEC) is submitting this report on the delimitation of constituency and ward boundaries in adherence to its constitutional mandate to delimit electoral constituency and ward boundaries, to be done “not less than five years and not more than seven years”; and complying with the timeline as stipulated in the NEC Electoral Calendar (2015-2019). The report is subject to Parliamentary approval, as enshrined in the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No 6 of 1991); which inter alia states delimitation of electoral boundaries to be done by NEC, while Section 38 (1) empowers the Commission to divide the country into constituencies for the purpose of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) using Single Member First- Past –the Post (FPTP) system. The Local Government Act of 2004, Part 1 –preliminary, assigns the task of drawing wards to NEC; while the Public Elections Act, 2012 (Section 14, sub-sections 1 &2) forms the legal basis for the allocation of council seats and delimitation of wards in Sierra Leone. The Commission appreciates the level of technical assistance, collaboration and cooperation it received from Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), the Boundary Delimitation Technical Committee (BDTC), the Boundary Delimitation Monitoring Committee (BDMC), donor partners, line Ministries, Departments and Agencies and other key actors in the boundary delimitation exercise. The hiring of a Consultant, Dr Lisa Handley, an internationally renowned Boundary delimitation expert, added credence and credibility to the process as she provided professional advice which assisted in maintaining international standards and best practices.