CHAPTER FOUR Children and the Armed Conflict in Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Province

SIERRA LEONE EASTERN PROVINCE afi B or B a fi n Guinea Guinea KOINADUGU KAMBIA BOMBALI ! PORT LOKO KONO Fandaa TONKOLILI 5 ! Henekuma WESTERN AREA ! Dunamor ! ! Powma KAILAHUN Fintibaya ! Siakoro MOYAMBA BO ! Konkonia ! Kondewakor Kongowakor !! KENEMA ! ! Saikuya ! M!okeni K! ongoadu Bongema II ! Poteya ! ! ! T o l i ! Komandor T o l i Kombodu ! ! ! ! ! ! Kondeya Fabandu Foakor ! !! BONTHE Thomasidu Yayima Fanema ! Totor ! !! Bendu Leimaradu ! ! ! Foindu ! ! Gbolia PUJEHUN !!Feikaya Sakamadu ! ! Wasaya! Liberia Bayawaindu ! Bawadu Jongadu Sowadu ! Atlantic Ocean Norway Bettydu ! ! Kawamah Sandia! ! ! ! ! ! Kamindo ! !! ! ! Makongodu ! Sam! adu Bondondor ! ! Teiya ! ! ! ! Wonia ! Tombodu n Primary School ! ! e wordu D Wordu C Heremakonoh !! ! !! ! Yendio-Bengu ! d !! Kwafoni n ! !Dandu Bumanja !Kemodu ! ! e ! Yaryah B Yuyah Mor!ikpandidu ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! Kondeya II ! r ! ! ! ! !! Kindia o ! ! Deiyor! II Pengidu a Makadu Fosayma Bumbeh ! ! an Kabaidu ! Chimandu ! ! ! Yaryah A ! Kondeya Kongofinkor Kondeya Primary School ! Sambaia p ! ! ! F!aindu m Budu I !! Fodaydu ! ! Bongema I a !Yondadu !Kocheo ! Kwakoima ! Gbandu P Foimangadu Somoya ! ! Budu II ! ! ! Koyah ! Health Centre Kamba ! ! Kunundu Wasaya ! ! ! ! Teidu ! Seidu Kondeya 1 ! ! Kayima A ! Sandema! ! ! suma II suma I Primary School ! ! ! ! Kayima B Koidundae !!! R.C. Primary School ! ! ! !! Wokoro UMC Primary School !! Sangbandor Tankoro ! ! Mafidu ! Dugbema ! Piyamanday ! Suma I Bendu ! Kayima D ! ! Kwikuma Gbeyeah B ! Farma Bongema ! Koekuma ! Gboadah ! ! ! ! Masaia ! Gbaiima Kombasandidu -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Bo District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN BO DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount NO. EMIS Name Of School Region District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total to School Per Child 1 311301222 Abdul Tawab Haikal Primary School South BO District Tikonko Samie 610 10000 6,100,000 Bo Kenema 2 319103274 Agape Way Christian Primary School South BO District Kakua 380 10000 Highway 3,800,000 3 311401201 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Valunia Baomahun 822 10000 8,220,000 4 310702210 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Jaima Koribondo 341 10000 3,410,000 5 310202206 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Bagbo Levuma 203 10000 2,030,000 Bumpe 6 310502209 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Makayoni 215 10000 Ngao 2,150,000 7 311401218 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Valunia Mandu 221 10000 2,210,000 8 310201205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Bagbo Momajoe 338 10000 3,380,000 Bumpe 9 310503217 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Walihun 264 10000 Ngao 2,640,000 Baoma 10 310403210 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Baoma 122 10000 Gbandi 1,220,000 Kenema 11 311401209 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Valunia 330 10000 Blango 3,300,000 12 311001208 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Lugbu Kpatobu 244 10000 2,440,000 13 310702215 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Jaiama Kpetema 212 10000 2,120,000 14 310402205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Baoma Ndogbogoma 297 10000 2,970,000 15 310201211 Ahmadiyya -

The Perceptions of Stakeholders on Post-War Reconstruction of Secondary Education in Kailahun District, Sierra Leone

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications ISSN (Online): 2581-6187 The Perceptions of Stakeholders on Post-War Reconstruction of Secondary Education in Kailahun District, Sierra Leone Yankuba Felix Moigua, Martha Fanta Mansaray Eastern Polytechnic, Kenema, Sierra Leone Abstract— The study investigated the perceptions of stakeholders on institutions to turn to. It is not surprising that literacy levels the problems and solutions of post war reconstruction of formal remained low due to the country‟s educational system and that secondary education in kailahun district which is located in the fewer than 15 percent of children aged between 5 .11 attended eastern province of sierra Leone, and is comprised of fourteen [14] schools and only 5 percent of children between 12 and 16 chiefdoms. The target group comprised of Inspectors/ Supervisors of years were in secondary schools. the ministry of Education, Science and Technology in kailahun district, NACSA, UNICEF,IRC,NRA, Principals, teachers, pupils, With the advent of the war, substantial portion of the community teachers associations of secondary schools and missions/ population displaced by the war were either in refugee camps proprietors in partnership management of secondary schools in the in Guinea or in Freetown and other bigger towns, the impact kailahun district. The study sample comprised of 97 respondents. The of the war on schooling and literacy level in Sierra Leone was study essentially involved the identification and description of devastating. Majority of the teachers were forced to flee to the stakeholders perceptions of problems and solutions in the postwar capital or out of the country and a lot of schools were either reconstruction of formal secondary education in Kailahun District in totally destroyed or damaged. -

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

Esia Volume 1: Executive Summary & Main Report

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FOR CT IN LUGBU CHIEFDOM BO DISTRICT ESIA VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & MAIN REPORT Prepared by CEMMATS Group Ltd on behalf of: SIERRA TROPICAL LIMITED (STL) June 2018 Freetown, Sierra Leone Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the Sierra Tropical Ltd Agricultural Project Volume 1: Executive Summary and Main Report DOCUMENT HISTORY Version History Date Reviewer Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the Sierra Tropical Ltd Title Agricultural Project Volume 1: Executive Summary and Main Report Anthony Mansaray; Arnold Okoni-Williams; Bartholomew Bockarie; Joe Authors Lappia; Leonard B. Buckle; Ralph Bona; Rashidu Sinnah; Vanessa James Date Written September 2016; updated June 2018 Subject Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Publisher CEMMATS Group Ltd Type Client Report Description ESIA for the Sierra Tropical Ltd Contributors Joseph Gbassa; Josephine Turay; Mariama Jalloh Format Source Text Rights © CEMMATS Group Ltd Identifier Language English Relation © CEMMATS Group Ltd, October 2016 ii Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the Sierra Tropical Ltd Agricultural Project Volume 1: Executive Summary and Main Report CEMMATS Group Ltd (hereafter, 'CEMMATS') has prepared this Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report for the sole use of the Client and for the intended purposes as stated in the Contract between the Client and CEMMATS under which this work was completed. This ESIA Report may not be relied upon by any other party without the express written agreement of CEMMATS and/or the Client. CEMMATS has exercised due and customary care in conducting this ESIA but has not, save as specifically stated, independently verified information provided by others. -

U N I T E D N a T I O

U N I T E D N A T I O N S Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs SIERRA LEONE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT SEPTEMBER 2003 KEY EVENTS district. A concern raised in Kono is that none of the Watsan implementing partners had the facilities or machines for testing water • Yellow Fever outbreak samples. This has been reported to the MOHS. • Security Council extends UNAMSIL’s mandate • UN Agencies and GoSL celebrate World Peace Day SECURITY HIGHLIGHTS • Nigerian lawmakers call on UNAMSIL Overall security UNAMSIL (United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone) reports the overall security situation in HUMANITARIAN HIGHLIGHTS the country to be calm. However there have been some concerns about security along the Yellow Fever outbreak border regions, particularly along the Mano The Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) River Union Bridge in the south. Similarly the has reported a total of 90 cases of Yellow Sierra Leone Police (SLP) are concerned Fever, from eight districts in the country: about the porous nature of the border in the Tonkolili, Bombali, Kenema, Koinadugu, Port Kamakwie, Tambakha and Koinadugu areas, Loko, Kambia and Kono. Of the 90 reported in the Northern Province that have resulted in cases (as of 29 September) four laboratory increased smuggling of goods across the cases were confirmed, all from the Tonkolili borders. The police have also reported hunters District, where majority of the suspected cases from Guinea, coming across, poaching and emanate from. Earlier, the MOHS gave out crossing back into Guinea. 100,000 doses of vaccine in four chiefdoms in the district. They have now finally secured UNAMSIL’s mandate extended funds to carry out mass immunization The UN Security Council has extended campaign in the remaining seven chiefdoms of UNAMSIL’s mandate, which was to expire on the district. -

Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997

1997 Human Rights Report: Sierra leone Page 1 of 20 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Sierra Leone Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1998. SIERRA LEONE Sierra Leone is controlled by a military junta. On May 25, dissident junior officers of the Republic of Sierra Leone Military Forces (RSLMF) violently seized power from the 14-month-old democratically elected Government of President Ahmed Tejan Kabbah. The United Nations Security Council condemned the overthrow of the government and called upon the military junta to restore the elected Government unconditionally. Major Johnny Paul Koroma, awaiting trial on charges stemming from a September 1996 coup attempt, was freed from prison and named Chairman of the new Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC). The AFRC immediately suspended the Constitution, banned political parties and all public demonstrations and meetings, and announced that all legislation would be made by military decree. Koroma invited the rebel Revolutionary United Front (RUF) to join the AFRC in exercising control over the country. The RUF quickly took control of the military junta, although Koroma remains nominal Chairman of the AFRC. Rule is arbitrary; maintenance of law and order has collapsed. -

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project, Search For

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project Search for Common Ground Background Over the next three-year period, Sierra Leone must capitalize on the opportunities provided by the end of the civil conflict to ensure a peaceful transition into a long-term development phase. These opportunities include: • the discourse of public participation and dialogue • tolerance for openness and freedom of the press • implementation of a decentralization policy and structural reforms. Media tolerance and diversification is central to a wider and broader range of available public information. A viable and functioning public information network supports deeper analysis on issues and the mobilization of the population for engagement in governance processes, including local and national elections, anti-corruption initiatives, and budgetary monitoring, among others. Search for Common Ground in Sierra Leone (SFCG) with the support of the United States Agency for International Development through cooperative agreement 636-A-00-05-00040 is supporting these transformation processes over the next three to five years. Capitalizing on new entry points created by governance reform and decentralization, SFCG, using its trusted media tools integrated with community outreach, will support the creation of demand for good governance and accountable leadership through participation, engagement and good citizenship. SFCG’s overarching goal for its democracy and governance project is to: Strengthen democratic governance in the districts of Kono, Kailahun, and Koinadugu, and Tongo Fields in Sierra Leone, which supports Special Objective #2 (SO2) under USAID/Sierra Leone’s Transition Strategy Phase 2, (FY 2004-2006). SFCG’s program objective is to: Stimulate an active citizenry. This supports Intermediate Result (IR) 2.2: “Citizens, local government, and CSOs better informed on democratic governance” of SO2. -

Reference Map of Kailahun, Eastern Province, Sierra Leone

MA002_Kailahun, Eastern Province Biama Gbogboragfeh Sawulla N ' Masundu Gbongbokoro Nongoua 0 3 ° 8 Kanekor Mak o na Tankoro Soa Nimikoro Koindu Mendekoma Nimiyama Gbane Kono Gandorhun GUINEA Reference map Tokpombu Kissi Gorama Kama of Foinba Kono Moimandu Kissi Gandohun li Dia Kangama Penguia Me Kailahun, Eastern Belebu Tolobu Teng Province, Malema Jerihun Moa Kangama Mano Sierra Leone Jerihun Saabendu Bandajuma Kéléma Baiama Sandialu Yawei GUINEA Kangahun Petema Kailahun Buedu Baoma Kissi Buobobu Woroma Tongi NORTHERN Dagbahun Sile Balahun Dodo Keya Malegohun Fobu Freetown Tongo Laoma Bandajuma Kpeje EASTERN West Giehun Talia Nyandehun Lalehun Lower Mende Luawa Panguma Bambara SOUTHERN Giehun Woa Giema Manowa Manowa Junction LIBERIA Dodo Kpeje Bongre e al Kenema M Foindu Belebu Kailahun Settlement Borders Lelehun Bendu Pendembu Capital National EASTERN Upper Bambara Province City un Gbolabu goh Mandulawahun Nia Town District Lago a auw Mano Levuma M village Chiefdom Baima Junction Vaahun Njaluahun Taninahun Bomaru Physical N Benduma Ma ° hi 8 Segbwema mb Komende Daru Mobai Baiwala e Lake Coastline Luyama Nongowa Mandu LIBERIA River Bombohun Transport Railway Jomu Gandohun o Dea Hangha Airport Roads Goma Nekabu Nyandehun ⛡ Port Primary Tikonko Gbaru Secondary Geblama Tertiary Jojoima Jawie 0 2 4 6 8 10 km Tokpombu Gofor Dama Data sources OpenStreetMap, Steward Project, COD-FOD Registry, Logistics Cluster La Malema Mo o gula rr M a Created 21 Oct 2014 / 11:00 UTC±00:00 m a w Map Document MA003_Reference_District a Projection / Datum WGS 1984 UTM Zone 29N Glide Number EP-2014-000039-SLE Joru Gaura Produced by MapAction Supported by www.mapaction.org [email protected] The depiction and use of boundaries, names and associated data shown Nomo here do not imply endorsement or Tunkia ´ acceptance by MapAction. -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

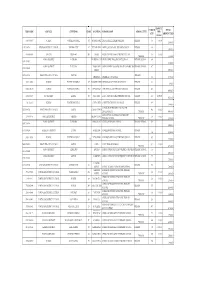

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K.