Dream Mines and Religious Identity in Twentieth-Century Utah I Ns Ights from the Norman C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of The

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of the Western Hemisphere, , , PART TWO of "The PROPHECYKEEPERS" TRILOGY , , Proceeds from this e-Book will eventually provide costly human translation of these prophecies into Asian Languages NORTH, , SOUTH , & CENTRAL , AMERICAN , INDIAN;, PACIFIC ISLANDER; , and AUSTRALIAN , ABORIGINAL , PROPHECIES, FROM "A" TO "Z" , Edited by Will Anderson, "BlueOtter" , , Compilation © 2001-4 , Will Anderson, Cabool, Missouri, USA , , Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson, "I am Mad Bear Anderson, and I 'walked west' in Founder of the American Indian Unity 1985. Doug Boyd wrote a book about me, Mad Bear : Movement , Spirit, Healing, and the Sacred in the Life of a Native American Medicine Man, that you might want to read. Anyhow, back in the 50s and 60s I traveled all over the Western hemisphere as a merchant seaman, and made contacts that eventually led to this current Indian Unity Movement. I always wanted to write a book like this, comparing prophecies from all over the world. The elders have always been so worried that the people of the world would wake up too late to be ready for the , events that will be happening in the last days, what the Thank You... , Hopi friends call "Purification Day." Thanks for financially supporting this lifesaving work by purchasing this e-Book." , , Our website is translated into many different languages by machine translation, which is only 55% accurate, and not reliable enough to transmit the actual meaning of these prophecies. So, please help fulfill the prophecy made by the Six Nations Iroquois Lord of the Confederacy or "Sachem" Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson -- Medicine Man to the Tuscaroras, and founder of the modern Indian Unity Movement -- by further supporting the actual human translation of these worldwide prophecy comparisons into all possible languages by making a donation, or by purchasing Book #1. -

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories Achievements of Lehi Citizens

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories Achievements of Lehi Citizens AdobeLehi Plant Airplane Flights in Lehi Alex ChristoffersonChampion Wrestler Alex Loveridge Home All About Food and Fuel/Sinclair Allred Park Alma Peterson Construction/Kent Peterson Alpine Fireplaces Alpine School BoardThomas Powers Alpine School District Alpine Soil/Water Conservation District Alpine Stake Alpine Stake Tabernacle Alpine, Utah American Dream Labs American Football LeagueDick Felt (Titans/Patriots) American Fork Canyon American Fork Canyon Flour Mill American Fork Canyon Mining District American Fork Canyon Power Plant American Fork Cooperative Institution American Fork Hospital American Fork, Utah American Fork, UtahMayors American Fork, UtahSteel Days American Legion/Veterans American Legion/VeteransBoys State American Patriotic League American Red Cross Ancient Order of United Workmen (AOUW) Ancient Utah Fossils and Rock Art Andrew Fjeld Animal Life of Utah Annie Oakley Antiquities Act Arcade Dance Hall Arches National Park Arctic Circle Ashley and Virlie Nelson Home (153 West 200 North) Assembly Hall Athenian Club Auctus Club Aunt Libby’s Dog Cemetery Austin Brothers Companies AuthorFred Hardy AuthorJohn Rockwell, Historian AuthorKay Cox AuthorLinda Bethers: Christmas Orange AuthorLinda JefferiesPoet AuthorReg Christensen AuthorRichard Van Wagoner Auto Repair Shop2005 North Railroad Street Azer Southwick Home 90 South Center B&K Auto Parts Bank of American Fork Bates Service Station Bathhouses in Utah Beal Meat Packing Plant Bear -

Events, Places and Things and Their Place in Lehi History

Events, Places and Things and their Place in Lehi History Abel John Evans Law Offices ● The Lehi Commercial and Savings Bank was the Law Offices of Abel John Evans in 1905. Adventureland Video ● Established in the Old Cooperative building at 197 East State in 1985. Alahambra Saloon ● This was a successful saloon ran by Ulysses S. Grant(not the President) for a few short years in the Hotel Lehi (Lehi Hotel) In 1891 through approximately 1895. ● The address was 394 West Main Street. American Fork Canyon Power Plant ● When the power plant was closed, one of the cabins was sold to Robert and Kathleen Lott in 1958 and it is their home today at 270 North 300 East American Fork Canyon Railroad ● Railroad that took men to the mines in American Fork Canyon ● Henry Thomas Davis helped build the railroad in American Fork Canyon American Savings and Loan Company ● Company founded by Lehi man John Franklin Bradshaw A.O.U.W. Lodge ● A.O.U.W. Lodge met in an upper room at the Lehi Commercial and Savings Bank in 1895. ● It stands for Ancient Order of United Workmen ● The AOUW was a breakoff of the Masons. Arley Edwards Barbershop ● Opened a barbershop in 195152 in the Steele Building at 60 West Main. Athenian Club ● The Athenian Club was organized on December 27, 1909 at the home of Emmerrette Smith. She was elected the first President ● Julia Child was elected vice President and Jane Ford was elected Secretary. ● There was a charter membership of 20 members ● The colors of the club were yellow and white ● They headed the drive for a Public Library. -

The Effect of the Rivalry Between Jesse Knight and Thomas Nicholls Taylor on Architecture in Provo, Utah: 1896-1915

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1991 The Effect of the Rivalry Between Jesse Knight and Thomas Nicholls Taylor on Architecture in Provo, Utah: 1896-1915 Stephen A. Hales Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hales, Stephen A., "The Effect of the Rivalry Between Jesse Knight and Thomas Nicholls Taylor on Architecture in Provo, Utah: 1896-1915" (1991). Theses and Dissertations. 4740. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4740 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LZ THE EFFECT OF THE RIVALRY BETWEEN JESSE KNIGHT AND THOMAS NICHOLLS TAYLOR ON architecture IN PROVO UTAH 189619151896 1915 A thesis presented to the department of art brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts 0 stephen A hales 1991 by stephen A hales december 1991 this thesis by stephen A hales is accepted in its present form by the department of art of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree master of arts i r rr f 1 C mark hamilton committee0amimmiweemee chilechair mark Johnjohndonjohnkonjohnmmitteekonoon committeec6mmittee -

The Ezra Booth Letters

IN THE ARCHIVES The Ezra Booth Letters Dennis Rowley BOTH EZRA BOOTH, a Methodist cleric from Mantua, Ohio, and the Booth letters are familiar to students of early Mormon history. Booth was the first apostate to write publicly against the new Church, and most standard histories include an account of his conversion and almost immediate apostacy.1 He joined the Church in June 1831 after seeing Joseph Smith miraculously heal the paralyzed arm of his neighbor, Mrs. John Johnson. He left on a mission to Missouri with Joseph Smith and twenty-six others later that summer. Apparently, he expected to convert many people and perform miracles similar to Joseph's through the power of the priesthood to which he had been newly ordained. When neither converts nor miracles were readily forthcoming and when he began to see frailties in Joseph Smith and other Church leaders (including seeming incon- sistencies in some of the Prophet's teachings), he became disaffected from the Church. On 6 September 1831, shortly after Booth returned to Ohio from his Mis- souri mission, a Church conference barred him from preaching as an elder.2 Shortly thereafter, he shared some of his negative feelings in a letter to the Reverend Ira Eddy, a presiding elder in the Methodist Circuit of Portage County, Ohio, and sent a second letter to Edward Partridge, attempting to dissuade him from further affiliation with the Mormons. During the months of October, November, and December 1831, Booth's initial letter to Eddy, his letter to Partridge, and an additional eight letters to Eddy, were published in a weekly newspaper, the Ohio Star, of Ravenna. -

I State Historic Preservation Officer Certification the Evaluated Significance of This Property Within the State Is

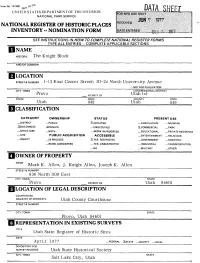

Form No. 10-300 (p&t-, \Q-1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS____ I NAME , HISTORIC The Knight Block AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 1~13 East Center Street; 20-24 North University Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Provo VICINITY OF Utah 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Utah 049 Utah 049 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC 2LOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM JXBUILDING(S) -XPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mark K. Alien, J. Knight Alien, Joseph K. Alien STREET & NUMBER 836 North 1100 East CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Utah 84601 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Utah County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Provo, Utah 84601 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Utah State Register of Historic Sites DATE April 1977 —FEDERAL .XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Utah State Historical Society CITY, TOWN STATE Salt Lake City, Utah DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .XORIGINALSITE _GOOD __RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED The Knight Block is a three story rectangular building, approximately 55 feet by 118 feet, housing a ground floor of retail space with a full basement and two upper floors of offices. -

SEPTEMBER 2019 (Continued from Previous Page) Nothing More Exciting Than to Travel with SUP Members and Have an Adventure! Stay Tuned

15 9 number ISSUE 169 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Friends, President’s Message . 1 We have had a great voter turn-out Membership Report . .. 2 in this year’s election as both candidates National Encampment . 3 endeavored to get their name and National News . 7 Pioneer Stories . 8 message out to as many chapters as National Calendar . 10 possible. Voting is now closed, ballots Chapter News . 11 will be counted and the winner is... Box Elder . .. 11 (come to Encampment and find out!). I Brigham Young . 12 hope everyone is making plans to come Cedar City . 13 to our 2019 LOGAN Encampment. Cotton Mission . 13 The committee from the Temple Fork Eagle Rock . 14 Chapter, headed by Smithfield Mayor Lehi . 14 Jeff Barnes and Richard Barrett, have Maple Mountain . 15 Morgan . 16 planned a super program for us. If you Murray . 17 haven’t come before, don’t miss this time! The treks are alway a Red Rocks . 18 highlight, speakers are dynamic, the food and performances are great, Salt Lake City . 18 plus the wonderful company will bring you back year after year. Salt Lake Pioneer . 19 Check our website or the recent Pioneer Magazine for application Settlement Canyon . 20 forms to register for Encampment. Sevier . 21 Temple Fork . .. 21 We must thank Bill Tanner and the Pioneer Editorial Board for Temple Quarry . .. 22 another superb edition of our magazine. The stained-glass pictures Timpanogos . .. 23 and articles showcasing our beautiful chapels, homes, and temples did Twenty Wells . 24 us proud! Next quarter’s Pioneer will celebrate the 150th anniversary Upper Snake River Valley . -

Dedication of the Newel Knight Grave Monument

Dedication of the Newel Knight Grave Monument In the spring of 1907, a party consisting of Jesse Knight; his daughter, Inez Knight Allen; his daughter-in-law, Lucy Jane B. Knight; an elder brother, Samuel R. Knight; President George H. Brimhall of Brigham Young University; and J. W. Townsend of Crete, Nebraska, visited the old campsite and made arrangements for a piece of ground on which to erect a monument for Jesse’s father. On this ground was erected an imposing granite shaft facing the highway and enclosed by an iron fence. On the shaft is inscribed the following bit of history: Erected 1908 NEWELL KNIGHT Born September 13, 1800; Died January 11, 1847 A member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints FATHER Who died during the hardships of our exodus from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City. “Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”—Matt. V:10 While there, President Brimhall, who was a gifted poet, composed the following lines in 1907 at the gravesite of Newel Knight and other pioneers who died in Niobrara, Nebraska on their journey west: Not backward, but onward and upward they looked; A fire in each bosom was burning. For the new land of promise the Lord had them booked And they yearned with and Israelite yearning. The comforts of home they had left far behind. The wilderness wild was around them. The voice of their God was the only one kind. And here the cold winter had found them. The smoke from their cabins arose to the sky— Their prayers of the morning and bedtime. -

“Pond Town” Changed to Salem “City of Peace” in 1865 by Joyce H

“Pond Town” Changed to Salem “City of Peace” in 1865 By Joyce H. Henderson I’ve taken material from Lee R. Taylor’s “Salem, The City of Peace” written in 1954. This history was revised in 1961 by Margrette Taylor, Mabel Koyle and Golda A. Adams, for and in behalf of Salem Camp and Mt. Loafer Camp of the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers. I’ve also taken information from “The Dream Mine Story” and a book of Schools and Schooling by Ted Hanks, Louise Measom and Beverly Davis. A monument was constructed on July 16, 1938, by Daughters of the Utah Pioneers located on the east side of the Salem Dam near the state highway which reads: “In 1851 David Fairbanks and David Crocket located land adjacent to a small stream at the head of Salem Lake and built a dam in 1856. Royal Durfey, Silas Hilman, Acquilla Hopper, Jacob Killian, Truman Tryon and their families settled Pond Town and began building a fort for protection against the Indians. The fort was 160 feet north and south and 150 feet east and west. The pond was found to be clear, sparkling water springing up from under earth banks in a hollow and wasting in a north-westerly direction into Utah Lake. These springs are probably fed by the drainage from beautiful Mt. Loafer of the Wasatch Range four or five miles to the southeast. This stream quenched the thirst in 1776 of Escalante and Dominique’s two Catholic Priests, large parties of helpers and Indian guides and Jedediah S. -

BYU Education Week Booklet

BYU EDUCATION August 19–23, 2019 | educationweek.byu.edu Helaman 5:12 BYU CONTINUING EDUCATION Program Highlights Campus Devotional Elder Gary E. Stevenson of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles Tuesday, August 20, 2019 Marriott Center 11:10 a.m. • Topics include marriage More than 1,000 classes and family, communication, health, history, fnance, the that Renew, Refresh, and arts, personal development, Recharge! a wide variety of gospel subjects, and more! • Come for a day, an evening, or the entire week! Evening Performances See pages 44–45 for information Beauty and the Beast, a SCERA Production GENTRI: The Gentlemen Trio Welcome to BYU Education Week Building Our Foundation upon Christ (Helaman 5:12) We are pleased to welcome you to BYU Education Week, a program now in its 97th year, with more TABLE OF CONTENTS than 1,000 classes to strengthen and enrich your life! Education Week brings together 240 REGISTRATION AND CLASS INFORMATION presenters, more than 600 volunteers, and hundreds of BYU employees to provide a unique, Registration and General Information 46–50 outstanding educational experience Monday Concurrent Sessions 4–5 This year’s theme—Building Our Foundation upon Christ—is taken from Helaman 5:12 Tuesday–Friday Concurrent Sessions 6–10 President Russell M Nelson taught, “Without our Redeemer’s infinite Atonement, not one Tuesday–Friday Class Titles 11–32, 37–38 of us would have hope of ever returning to our Heavenly Father Without His Resurrection, Continuing Legal Education Classes 39 death would be the end Our Savior’s Atonement -

Disenchanted Lives Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism Among The

© 2015 Edward Marshall Brooks III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DISENCHANTED LIVES: APOSTASY AND EX•MORMONISM AMONG THE LATTER•DAY SAINTS By EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School•New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Dorothy L. Hodgson And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Disenchanted Lives: Apostasy and Ex-Mormonism among the Latter-day Saints by EDWARD MARSHALL BROOKS III Dissertation Director: Dorothy L. Hodgson This dissertation ethnographically explores the contemporary phenomenon of religious apostasy (that is, rejecting ones religious faith or church community) among current and former members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (aka Mormons). Over the past decade there has been increasing awareness in both the institutional church and the popular media that growing numbers of once faithful church members are becoming dissatisfied and disenchanted with their faith. In response, throughout Utah post-Mormon and ex-Mormon communities have begun appearing offering a social community and emotional support for those transitioning out of the church. Through fifteen months of ethnographic research in the state of Utah I investigated these events as they unfolded in people’s everyday lives living in a region of the country wholly dominated by the Mormon Church’s presence. In particular, I conducted participant observation in church services, ex-Mormon support group meetings, social networks and family events, as well as in-depth interviews with current and former church members. -

Magic and the Supernatural in Utah Folklore

Magic and the Supernatural in Utah Folklore Wayland D. Hand No BRANCH OF STUDY, academic or popular, penetrates as deeply into man's intuitive life or mirrors his contemplative self as clearly as folklore. Folklore lays bare man's myriad fears and anxieties, while at the same time in full coun- terpoint it reveals his whimsy, his visions, and his flights of fancy that ennoble and exalt. It is for these reasons, and particularly because of its heavy com- ponent of magic and the supernatural, that psychologists from Wundt and Freud to Jung and his modern disciples have found in folklore a veritable seed- bed for their work. The materials for a study of popular culture in Utah are gradually being assembled. As one can expect, they bear the impress of the common American culture of which they were born, yet many of these products of the popular mind exhibit features of their Rocky Mountain habitat and of their Mormon religious legacy as well. Utah folklore, like Joseph's coat of many colors, contains patterns and strands from divers sources, foreign as well as domestic. These sturdy fibers were either woven into the basic fabric of folklore during the Utah period, or were cultural importations so basic and widespread as to have helped shape Mormon folklore from the beginning. Thus before the midnineteenth century the early fabric of Mormon folklore included the hardy homespun cultural goods of New England and New York strongly webbed with the basic English and Dutch folklore of the people who had colonized these states. The move- ment of the Mormons across the gateway states of Pennsylvania and Ohio brought ethnic reinforcement, principally German and Pennsylvania Dutch.