Formerly the Property of a Lawyerâ•Ž: Books That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jottings of Louisiana

H&3 Arcs V-sn^i Copyright^ COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT. JOTTINGS OF LOUISIANA ILLUSTRATED HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS LANDMARKS OF NEW ORLEANS, And the Only Remaining Buildings of Colonial Days. "They do not only form part of the History of the United States, but also of France and Spain." BY WILLIS J. ROUSSEL New Orleans, La. (Copyrighted January 3rd, 1905.; Price, 50 Cents. 1905. Mkndola Bros. Publishers, new orleans, la. LIBRARY of CONGRESS fwo Copies Received FEB 24 1905 , Qopyrigm tmry iUiSS CX* XXc. NO! COPY B. : POETICAL JOTTINGS OF THE HISTORY OF LOUISIANA. —f-f — BY CHARLES UAYARPE The following quotations are taken from the History of Louisiana by Charles Gayarre, the eminent writer and historian, and will no doubt prove to be a very appropriate preface to this work, as it will admit a basis of comparison for "Louisiana as it is to-day." After a masterly and graceful preliminary the learned historian said "I am willing to apply that criterion to Louisiana, considered both physically and historically; I am willing that my native State, which is but a fragrant of what Louisiana formerly was, should stand and fall by that test, and do not fear to approach with her the seat of judgment. I am prepared to show that her history is full of poetry of the highest order, and of the most varied nature. I have studied the subject "con amore," and with such reverential enthusiasm, and I may say with such filial piety, that it has grown upon my heart as well as upon my mind. -

Lawyers Who Rely on FORMDISKTM

�� The Needle In A Haystack Complex financial litigation cases often hinge on the engagement of experts who find the needle in a haystack. A substantial edge is gained when you have Legier & Company’s Forensic Accounting and Expert Witness Group on your team to help you find obscured financial facts that can ensure your success. �� Expert Testimony • Fraud & Forensic Accounting • Calculating and Refuting Financial Damages Business Valuations • Bankruptcies • Shareholder Disputes • Lost Profits • Business Interruptions For more information, contact William R. Legier (504) 599-8300 apac Forensic and Investigative CPAs 1100 Poydras Street • 34th Floor • Energy Centre • New Orleans, LA 70163 Telephone (504) 561-0020 • Facsimile (504) 561-0023 • http://www.lmcpa.com FORMDISKTM 2009 ORDER NOW! There has never been a better time to buy FORMDISKTM, an extensive collection of annotated civil forms. Order FORMDISKTM 2009 now for the low price of $198. For 2008 customers, the 2009 update is now available for only $80. Join thousands of Louisiana lawyers who rely on FORMDISKTM. FORMDISKTM 2009 Order Form Name: ___________________________ Bar Roll #: __________ Firm Name: _______________________ Address: _______________________________ City: __________________ State: _____ Zip: _________ Phone #: _____________________ Fax #: ____________________ Email Address:____________________ I have (check one): � PC � Mac I use (check one): � Word � Word Perfect � Other _______________ I want: qty. _____ $19800 Low Price qty. _____ $8000 Update Price (for 2008 customers only) qty. _____ $2500 Each additional disk � Enclosed is my check made out to Template, Inc. for the amount of $ ________________ � Charge $__________ to my: � VISA � Mastercard Card #: _____________________________________________ Exp. Date: _________________ Cardholder Signature: ____________________________________________________________________ Please allow 4-6 weeks delivery. -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

FALL 2009 Vented the Idea of Democracy

TULANEUNIVERSITYLAWSCHOOL TULANE VOL. 27–NO. 2 LAWYER F A L L 2 0 0 9 TAKING THE LAW THISISSUE IN THEI RHANDS ALETTERFROMINTERIM DEANSTEPHENGRIFFIN TULANELAWSTUDENTS I CLASSICALATHENIAN ANCESTRYOFAMERICAN ACTINTHEPUBLICINTEREST FREEDOMOFSPEECH I HONORROLLOFDONORS STEPHENGRIFFIN INTERIMDEAN LAURENVERGONA EDITORANDEXECUTIVEASSISTANTTOTHEINTERIMDEAN ELLENJ.BRIERRE DIRECTOROFALUMNIAFFAIRS TA NA C O M A N ARTDIRECTIONANDDESIGN SHARONFREEMAN DESIGNANDPRODUCTION CONTRIBUTORS LINDSAY ELLIS KATHRYN HOBGOOD NICKMARINELLO M A RY M O U TO N TULANELAWSCHOOLHONORROLLOFDONORS N E W WAV E S TA F F Donor lists originate from the Tulane University Office of Development. HOLMESRACKLEFF Lists are cataloged in compliance with the Tulane University Style Guide, using a standard format which reflects name preferences defined in the RYA N R I V E T university-wide donor database, unless a particular donation requires FRANSIMON specific donors’ preferences. TULANEDEVELOPMENT TULANE LAW CLINIC CONTRIBUTORS LIZBETHTURNER NICOLEDEPIETRO BRADVOGEL MICHAELHARRINGTON KEITHWERHAN ANDREWROMERO TULANELAWYER is published by the PHOTOGRAPHY Tulane Law School and is sent to the school’s JIM BLANCHARD, illustration, pages 3, 49, 63; CLAUDIA L. BULLARD, page alumni, faculty, staff and friends. 39; PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO/Tulane University Publications, inside cover, pages 2, 8, 12, 32, 48, 50, 53, 62; FEDERAL LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CENTER COMMITTEE, page 42; GLOBAL ENERGY GROUP LTD., page 10; JACKSON HILL, Tulane University is an Affirmative Action/Equal pages 24–25; BÍCH LIÊN, page 40 bottom;THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR Employment Opportunity institution. RESEARCH ON WOMEN, page 38; TRACIEMORRISSCHAEFER/Tulane University Publications, pages 44–45, 57; ANDREWSEIDEL, page 11; SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LTD., page 40 top; TULANE PUBLIC RELATIONS, page 47, outer back cover;EUGENIAUHL, pages 1, 26–28, 31, 33;TOM VARISCO, page 51; LAUREN VERGONA, pages 6, 7, 45–46; WALEWSKA M. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

Complete V.5 Number 1

Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 5 Number 1 200 Years of Statehood, 300 Years of Civil Article 23 Law: New Perspectives on Louisiana's Multilingual Legal Experience 10-2012 Complete V.5 Number 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Complete V.5 Number 1, 5 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2012) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol5/iss1/23 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 5 Number 1 October 2012 ___________________________________________________________________________ 200 YEARS OF STATEHOOD, 300 YEARS OF CIVIL LAW: NEW PERSPECTIVES ON LOUISIANA’S MULTILINGUAL LEGAL EXPERIENCE ARTICLES . Judicial Review in Louisiana: A Bicentennial Exegesis ........................................................ Paul R. Baier & Georgia D. Chadwick . De Revolutionibus: The Place of the Civil Code in Louisiana and in the Legal Universe .................................................................. Olivier Moréteau NOTES . Clashes and Continuities: Brief Reflections on the “New Louisiana Legal History” ................................ Seán Patrick Donlan . Making French Doctrine Accessible to the English-Speaking World: The Louisiana Translation Series .................................................................... Alexandru-Daniel On CIVIL LAW TRANSLATIONS . Louisiana Civil Code - Code civil de Louisiane Preliminary Title; Book III, Titles 3, 4 and 5 ...................... with Introduction by Olivier Moréteau ESSAY . The Case for an Action in Tort to Restrict the Excessive Pumping of Groundwater in Louisiana .................................................................................... John B. Tarlton REDISCOVERED TREASURES OF LOUISIANA LAW . -

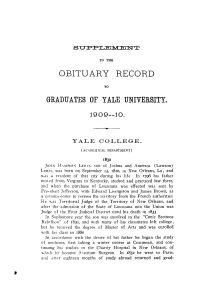

Obituary Record

S U TO THE OBITUARY RECORD TO GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVEESITY. 1909—10. YALE COLLEGE. (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1832 JOHN H \MPDFN LEWIS, son of Joshua and America (Lawson) Lewis, was born on September 14, 1810, m New Orleans, La, and was a resident of that city during his life In 1796 his father moved from Virginia to Kentucky, studied and practiced law there, and when the purchase of Louisiana was effected was sent by President Jefferson, with Edward Livingston and James Brown, as a commisMoner to receive the territory from the French authorities He was Territorial Judge of the Territory of New Orleans, and after the admission of the State of Louisiana into the Union was Judge of the First Judicial District until his death in 1833 In Sophomore year the son was involved in the "Conic Sections Rebellion" of 1830, and with many of his classmates left college, but he received the degree of Master of Arts and was enrolled with his class in 1880 In accordance with the desire of his father he began the study of medicine, first taking a winter course at Cincinnati, and con- tinuing his studies in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, of which he became Assistant Surgeon In 1832 he went to Pans, and after eighteen months of study abroad returned and grad- YALE COLLEGE 1339 uated in 1836 with the first class from the Louisiana Medical College After having charge of a private infirmary for a time he again went abroad for further study In order to obtain the nec- essary diploma in arts and sciences he first studied in the Sorbonne after which he entered -

Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary

Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 8 Number 2 Article 9 12-31-2015 Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary Yaëll Emerich Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Yaëll Emerich, Louisiana Property Law—The Civil Code, Cases and Commentary, 8 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2015) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol8/iss2/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS JOHN A. LOVETT, MARKUS G. PUDER & EVELYN L. WILSON, LOUISIANA PROPERTY LAW—THE CIVIL CODE, CASES AND COMMENTARY (Carolina Academic Press, Durham, North Carolina 2014) Reviewed by Yaëll Emerich* Although this interesting work, by John A. Lovett, Markus G. Puder and Evelyn L. Wilson, styles itself as “a casebook about Louisiana property law,”1 it nevertheless has some stimulating comparative insights. The book presents property scholarship from the United States and beyond, taking into account property texts from other civilian and mixed jurisdictions such as Québec, South Africa and Scotland. As underlined by the authors, Louisiana’s system of property law is a part of the civilian legal heritage inherited from the French and Spanish colonisation and codified in its Civil Code: “property law . is one of the principal areas . where Louisiana´s civilian legal heritage has been most carefully preserved and where important substantive differences between Louisiana civil law and the common law of its sister states still prevail.”2 While the casebook mainly scrutinizes Louisiana jurisprudence and its Civil Code in local doctrinal context, it also situates Louisiana property law against a broader historical, social and economic background. -

2019-2020 Missouri Roster

The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 Secretary of State John R. Ashcroft State Capitol Room 208 Jefferson City, MO 65101 www.sos.mo.gov John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Cover image: A sunrise appears on the horizon over the Missouri River in Jefferson City. Photo courtesy of Tyler Beck Photography www.tylerbeck.photography The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 A directory of state, district, county and federal officials John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Office of the Secretary of State State of Missouri Jefferson City 65101 STATE CAPITOL John R. Ashcroft ROOM 208 SECRETARY OF STATE (573) 751-2379 Dear Fellow Missourians, As your secretary of state, it is my honor to provide this year’s Mis- souri Roster as a way for you to access Missouri’s elected officials at the county, state and federal levels. This publication provides contact information for officials through- out the state and includes information about personnel within exec- utive branch departments, the General Assembly and the judiciary. Additionally, you will find the most recent municipal classifications and results of the 2018 general election. The strength of our great state depends on open communication and honest, civil debate; we have been given an incredible oppor- tunity to model this for the next generation. I encourage you to par- ticipate in your government, contact your elected representatives and make your voice heard. Sincerely, John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State www.sos.mo.gov The content of the Missouri Roster is public information, and may be used accordingly; however, the arrangement, graphics and maps are copyrighted material. -

LOUISIANA CITATION and STYLE MANUAL, 79 La

LOUISIANA CITATION AND STYLE MANUAL, 79 La. L. Rev. 1239 79 La. L. Rev. 1239 Louisiana Law Review Summer, 2019 Citation and Style Manual The Board of Editors Volume 79 Copyright © 2019 by the Louisiana Law Review LOUISIANA CITATION AND STYLE MANUAL First Edition *1240 Last updated: 4/2/2019 2:39 PM. Published and Distributed by the Louisiana Law Review LSU Paul M. Hebert Law Center 1 E. Campus Dr., Room W114 Baton Rouge, LA 70803 TABLE OF CONTENTS § 1 Authority 1244 § 2 Typography & Style 1245 § 3 Subdivisions & Internal Cross-References 1249 § 4 Louisiana Cases 1251 § 5 Statutory Sources 1252 § 6 Louisiana Session Laws & Bills 1254 § 7 Louisiana Administrative & Executive Sources 1255 § 8 Louisiana Civil Law Treatise 1255 § 9 French Treatise & Materials 1256 § 10 Archiving Internet Sources 1256 *1242 INTRODUCTION The Louisiana Citation and Style Manual 1 is the successor to the Streamlined Citation Manual. 2 The SCM began in 1984 as “a list of guidelines applicable to the technical aspects of the legal articles, commentaries on legislation or cases, and book reviews published in the [Louisiana Law Review].” 3 In this sense, the Manual is no different. The original SCM served two purposes: first, it stated the general Bluebook rules governing citation format; and second, it noted specific deviations from The Bluebook. The Manual honors the spirit of the SCM, builds on its foundations, and adds a third purpose to this list: in addition to providing common Bluebook rules and deviations, it also serves as an expression of the editorial policy of the Louisiana Law Review (“the Law Review”). -

RG 68 Master Calendar

RG 68 MASTER CALENDAR Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Archives May 2012 Date Description 1387, 1517, 1525 Legal document in French, Xerox copy (1966.011.1-.3) 1584, October 20 Letter, from Henry IV, King of France, to Francois de Roaldes (07454) 1640, August 12 1682 copy of a 1640 Marriage contract between Louis Le Brect and Antoinette Lefebre (2010.019.00001.1-.2) 1648, January 23 Act of sale between Mayre Grignonneau Piqueret and Charles le Boeteux (2010.019.00002.1-.2) 1680, February 21 Photostat, Baptismal certificate of Jean Baptoste, son of Charles le Moyne and marriage contract of Charles le Moyne and Catherine Primot (2010.019.00003 a-b) 1694 Reprint (engraving), frontspiece, an Almanack by John Tulley (2010.019.00004) c. 1700-1705 Diary of Louisiana in French (2010.019.00005 a-b) c. 1700 Letter in French from Philadelphia, bad condition (2010.019.00006) 1711, October 18 Document, Spanish, bound, typescript, hand-illustrated manuscript of the bestowing of a title of nobility by Charles II of Spain, motto on Coat of Arms of King of Spain, Philippe V, Corella (09390.1) 1711, October 18 Typescript copy of royal ordinance, bestows the title of Marquis deVillaherman deAlfrado on Dr. Don Geronina deSoria Velazquez, his heirs and successors as decreed by King Phillip 5th, Spain (19390.2) 1714, January 15 English translation of a letter written at Pensacola by M. Le Maitre, a missionary in the country (2010.019.00007.1-.29) 1714 Document, translated into Spanish from French, regarding the genealogy of the John Douglas de Schott family (2010.019.00008 a-b) 1719, December 29 Document, handwritten copy, Concession of St. -

The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code, 19 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 19 | Number 1 Legislative Symposium: The 1958 Regular Session December 1958 The iH story and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code John T. Hood Jr. Repository Citation John T. Hood Jr., The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code, 19 La. L. Rev. (1958) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol19/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History and Development of the Louisiana Civil Code* John T. Hood, Jr.t The Louisiana Civil Code has been called the most perfect child of the civil law. It has been praised as "the clearest, full- est, the most philosophical, and the best adapted to the exigencies of modern society." It has been characterized as "perhaps the best of all modern codes throughout the world." Based on Roman law, modeled after the great Code Napoleon, enriched with the experiences of at least twenty-seven centuries, and mellowed by American principles and traditions, it is a living and durable monument to those who created it. After 150 years of trial, the Civil Code of Louisiana remains venerable, a body of substantive law adequate for the present and capable of expanding to meet future needs. At this Sesquicentennial it is appropriate for us to review the history and development of the Louisiana Civil Code.