Napoleon Review Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernist Aesthetics and the Artificial Light of Paris: 1900 to 1939

Modernist Aesthetics and the Artificial Light of Paris: 1900 to 1939 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Elizabeth Reddy (MA Cantab) School of English University of Leicester February 2017 2 ABSTRACT Modernist Aesthetics and the Artificial Light of Paris: 1900 to 1939 Emma Elizabeth Reddy In this project the fields of modernist studies and science converge on the topic of lighting. My research illuminates a previously neglected area of modernism: the impact of artificial lighting on American modernist literature written in Paris between 1900 and 1939. Throughout that period, Paris maintained its position as an artistic centre and emerged as a stage for innovative public lighting. For many, the streets of Paris provided the first demonstration of electricity’s potential. Indeed, my research has shown that Paris was both the location of international expositions promoting electric light, as well as a city whose world-class experiments in lighting and public lighting displays were widely admired. Therefore, I have selected texts with a deep connection to Paris. While significant scholarship exists in relation to Parisian artificial lighting in fine art, a thorough assessment of the impact of lighting on the modern movement is absent from recent critical analysis. As such, this thesis seeks to account for literary modernism in relation to developments in public and private lighting. My research analyses a comprehensive range of evocations of gas and electric light to better understand the relationship between artificial light and modernist literary aesthetics. This work is illuminating for what it reveals about the place of light in the modern imagination, its unique symbolic and metaphorical richness, as well as the modern subject’s adaptability to technological change more broadly. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

ABSTRACT Multi Objective Optimization for Seismology (MOOS)

ABSTRACT Multi Objective Optimization for Seismology (MOOS), with Applications to the Middle East, the Texas Gulf Coast, and the Rio Grande Rift Mohit Agrawal, Ph.D. Chairperson: Robert J. Pulliam, Ph.D. We develop and apply new modeling methods that make use of disparate but complementary seismic “functionals,” such as receiver functions and dispersion curves, and model them using a global optimization method called “Very Fast Simulated Annealing” (VFSA). We apply aspects of the strategy, which we call “Multi Objective Optimization for Seismology” (MOOS), to three broadband seismic datasets: a sparse network in the Middle East, a closely-spaced linear transect across Texas Gulf Coastal Plain, and a 2D array in SE New Mexico and West Texas (the eastern flank of the Rio Grande Rift). First, seismic velocity models are found, along with quantitative uncertainty estimates, for eleven sites in the Middle East by jointly modeling Ps and Sp receiver functions and surface (Rayleigh) wave group velocity dispersion curves. These tools demonstrate cases in which joint modeling of disparate and complementary functionals provide better constraints on model parameters than a single functional alone. Next, we generate a 2D stacked receiver function image with a common conversion point stacking technique using seismic data from a linear array of 22 broadband stations deployed across Texas’s Gulf Coastal Plain. The image is migrated using velocity models found by modeling dispersion curves computed via ambient noise cross-correlation. Our results show that the Moho disappears outboard of the Balcones Fault Zone and that a significant, negative-polarity discontinuity exists beneath the Coastal Plain. -

Protecting the Victims of Armed Conflict

KEITH DONE FINAL.DOC08/20/99 4:32 PM Remarks RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES: PROTECTING THE VICTIMS OF ARMED CONFLICT JUSTICE KENNETH J. KEITH† TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...........................................................................................1082 The Battle of Agincourt.......................................................................1083 I. Substantive Legal Limits on Warfare .............................................1088 II. Rules Facilitating Communication................................................1097 III. The Levels of Responsibility ........................................................1099 IV. The Legal Character of the Rules................................................1102 A. The Autonomy of the Rules..............................................1102 B. The Stability of the Rules ..................................................1105 C. The Universality of the Rules ...........................................1106 D. The Underlying and Competing Moral and Military Considerations ..........................................1107 E. The Balance of Rights and Obligations ...........................1108 V. Positive Obligations.........................................................................1110 VI. Sanctions and Forces for Compliance .........................................1117 Appendix: Fundamental Rules of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts.................................1131 † Judge of the New Zealand Court of Appeal, Professor Emeritus, Victoria University of -

Geology Alumni Newsletter | Fall 2012

DEPARTMENT OF GeologY Alumni Newsletter | Fall 2012 The scientist is motivated primarily by curiosity and a desire for truth. -Irving Langmuir 1 August 2012 Dear Alumni and Friends of Baylor Geology: There is an old Chinese proverb “we live in interesting times”, and that has certainly been the case. We now have a new Strategic Plan for Baylor University termed Pro Futuris (http://www.baylor.edu/ profuturis/) that has been intentionally written with rather vague language so that Departments, Colleges, Schools and Centers can respond more specifically in order to flesh out the “Aspirational Statements”. Having been involved early in the strategic planning process as both Chair and a member of the Geology Department, I can honestly say that the administration seriously considered all input receiving in the information gathering process, which is apparent in the final document that was adopted. It seems clear to me that in the new plan Baylor sees growth and improvement in the STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) as vital to its future aspirations of becoming a major research university, but at the same time is not stepping back from its commitment to excellence in undergraduate education. The fall semester of 2011 saw the Department start searches for tenure-track Assistant Professors in Applied Geophysics and Mineralogy-Petrology, but unfortunately both resulted in failure to secure hires. The Applied Geophysics search was resumed this fall, and a search for a Senior-level Paleoclimatologist is also underway. Two additional faculty hires requested for next year are in water-related research and in Petrology. Bill Hockaday’s new “Paul Marchand Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Laboratory” was finally completed, the NMR installed, and a formal dedication is planned. -

Wednesday, April 14Th 2021 the Honorable Joseph R. Biden Jr. The

Wednesday, April 14th 2021 The Honorable Joseph R. Biden Jr. The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20500 Dear President Joe Biden, As scientists, engineers, and public health experts, we welcome the important early steps you have taken to lay the groundwork for science-based policymaking, including rejoining the Paris Agreement and halting or reversing harmful regulatory rollbacks. Devastating climate impacts are already unfolding across the country and around the world. The science shows we must take bold actions now to sharply reduce heat-trapping emissions, limit climate change, and protect public health. As we endeavor to build a safer, more resilient world, centering the voices and needs of communities disproportionately impacted by environmental and climate injustices is essential. The global effort to limit warming to well below 2° Celsius, as called for in the Paris Agreement, has reached a critical point. Worldwide heat-trapping emissions are still far above where they need to be to stave off the worst climate harms. The United States, as one of the world's biggest contributors to global heat-trapping emissions, must take responsibility and commit to cutting its emissions by at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and transitioning to a net-zero emissions economy no later than 2050. This goal is both technically feasible and necessary—now we need action. We now call on your administration, working with Congress, to take strong, concrete measures across the economy to ensure the United States will meet this robust target. Emission reductions from the transportation and power sectors—the two leading sources of US heat-trapping emissions—must be prioritized, along with investments and policies that create good-paying jobs and further climate resilience, environmental justice, and racial equity. -

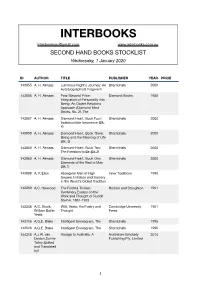

Second Hand Jan 2020

INTERBOOKS [email protected] www.interbooks.com.au SECOND HAND BOOKS STOCKLIST Wednesday, 1 January 2020 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 143055 A. H. Almaas Luminous Night's Journey: An Shambhala 2000 Autobiographical Fragment 143056 A. H. Almaas Pearl Beyond Price: Diamond Books 1988 Integration of Personality into Being: An Object Relations Approach (Diamond Mind Series, No. 2), The 143057 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Four: Shambhala 2000 Indestructible Innocence (Bk. 4) 143058 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Three: Shambhala 2000 Being and the Meaning of Life (Bk. 3) 143059 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Two: Shambhala 2000 The Freedom to Be (Bk.2) 143060 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book One: Shambhala 2000 Elements of the Real in Man (Bk.1) 143088 A. P. Elkin Aboriginal Men of High Inner Traditions 1993 Degree: Initiation and Sorcery in the World's Oldest Tradition 143359 A.C. Harwood The Faithful Thinker: Hodder and Stoughton 1961 Centenary Essays on the Work and Thought of Rudolf Steiner, 1861-1925 143348 A.G. Stock, W.B. Yeats: His Poetry and Cambridge University 1961 William Butler Thought Press Yeats 143116 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 143516 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 144318 A.J.W. van Voyage to Australia, A Australian Scholarly 2014 Delden,Dorine Publishing Pty, Limited Tolley (Edited and Translated by) !1 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 144236 A.L. Where Is Bernardino? Two Rivers Press 1982 Staveley,Nonny Hogrogian 143361 A.L. Stavely Themes: I Two Rivers Press 143362 A.L. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2016 ‘Our Bonaparte?’: Republicanism, Religion, and Paranoia in New England and the Mid- Atlantic, 1789-1830 Tarah L. (Tarah Lorraine) Luke Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ‘OUR BONAPARTE?’: REPUBLICANISM, RELIGION, AND PARANOIA IN NEW ENGLAND AND THE MID-ATLANTIC, 1789-1830 By TARAH LORRAINE LUKE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Tarah Luke defended this dissertation on October 28, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Martin Munro University Representative Andrew Frank Committee Member Maxine Jones Committee Member G. Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii Dedicated to my wonderful parents and my extremely supportive and helpful husband, for always helping me above and beyond, especially when I thought I could not go any further. And to Max, for everything else. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nobody writes a dissertation alone. Or at least they shouldn’t. I was fortunate to have my parents, Jim and Jodie Luke, behind me on every step and every page of this journey. My father in particular was instrumental in making sure that I worked, and when I didn’t, I heard about it from him. -

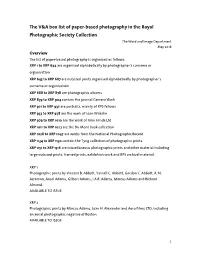

XRP Box List for PDF ER and DC Edits

The V&A box list of paper-based photography in the Royal Photographic Society Collection The Word and Image Department May 2018 Overview The list of paper-based photography is organised as follows: XRP 1 to XRP 644 are organised alphabetically by photographer’s surname or organisation XRP 645 to XRP 687 are outsized prints organised alphabetically by photographer’s surname or organisation XRP 688 to XRP 878 are photographic albums XRP 879 to XRP 904 contain the journal Camera Work XRP 921 to XRP 932 are portraits, mainly of RPS fellows XRP 933 to XRP 978 are the work of Joan Wakelin XRP 979 to XRP 1010 are the work of John Hinde Ltd XRP 1011 to XRP 1027 are the Du Mont book collection XRP 1028 to XRP 1047 are works from the National Photographic Record XRP 1134 to XRP 1150 contain the Tyng collection of photographic prints XRP 1151 to XRP 1516 are miscellaneous photographic prints and other material including large outsized prints, framed prints, exhibition work and RPS archival material. XRP 1 Photographic prints by Vincent B. Abbott, Yarnall C. Abbott, Gordon C. Abbott, A. N. Acraman, Ansel Adams, Gilbert Adams, J.A.R. Adams, Marcus Adams and Richard Almond. AVAILABLE TO ISSUE XRP 2 Photographic prints by Marcus Adams, Joan H. Alexander and Aero Films LTD, including an aerial photographic negative of Boston. AVAILABLE TO ISSUE 1 XRP 3 Photographic prints by John. H. Ahern, Rao Sahib Aiyar, G.S. Akaksu, W.A. Alcock, R.F. Alderton, L.E. Aldous, Edward Alenius, B. Alfieri (snr), B. -

Citation Style Copyright Esdaile, Charles: Rezension Über: Philip Dwyer, Citizen Emperor. Napoleon in Power, 1799-1815, London

Citation style Esdaile, Charles: Rezension über: Philip Dwyer, Citizen Emperor. Napoleon in Power, 1799-1815, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, in: Reviews in History, 2015, January, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/1707, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1707 copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). Napoleon Review Article Napoleon: Soldier of Destiny Michael Broers London, Faber & Faber, 2014, ISBN: 9780571273430; 400pp. Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power, 1799-1815 Philip Dwyer London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, ISBN: 9780747578086; 816pp. Napoleon Alan Forrest London, Quercus, 2011, ISBN: 9781849164108; 352pp. Napoleon: the End of Glory Munro Price Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN: 9780199934676; 344pp. Forging Napoleon’s Grande Armée: Motivation, Military Culture and Masculinity in the French Army, 1800-1808 Michael J. Hughes New York, NY, New York University Press, 2012, ISBN: 9780814737484; 296pp. 200 years on, the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte continues to fascinate, and it is therefore no surprise to find that the bicentenary of his downfall has seen the publication of a number of major works by leading specialists in the Napoleonic epoch. With Britain currently in the grip of remembrance for the First World War, meanwhile, this seems doubly apposite: a century ago the words ‘the great war’ were -

Emeritus Admins Faculty Staff

Department of Geosciences One Bear Place #97354 Waco, TX 76798-7354 Change Service Requested Geosciences ALUMNI NEWSLETTER | FALL 2018 Faculty Staff Dr. Stacy Atchley Dr. Lee Nordt Sharon Browning Chairman & Professor Dean, College of Arts & Teaching Lab Coordinator Sciences & Professor Dr. Peter Allen Wayne Hamilton Professor Dr. Daniel Peppe Program Consultant, Associate Professor & Laboratory Safety Coordinator Dr. Kenny Befus Graduate Program Director Assistant Professor Liliana Marin Dr. Elizabeth Petsios Geoscience Instrumentation Specialist, Dr. Vincent Cronin Assistant Professor Luminescence Geochronology Research Professor Dr. Jay Pulliam Tim Meredith Dr. Steven Driese W.M. Keck Foundation Instrumentation Specialist and Associate Dean for Research, Professor of Geophysics Computer Systems Admin, Graduate School & Professor Paleomagnetism and Geophysics Labs Dr. Joe Yelderman Dr. John Dunbar Professor Dr. Ren Zhang Associate Professor Stable Isotope Mass Dr. Steve Dworkin Spectrometry Technician Professor & Undergraduate Program Director Dr. Steve Forman Emeritus Professor Dr. James Fulton Dr. Harold Beaver Admins Assistant Professor Dr. Rena Bonem Dr. Tom Goforth Dr. Don Greene Paulette Penney Dr. Don Parker 04 07 43 50 Professor Office Manager Dr. William Hockaday Janelle Atchley Associate Professor Administrative Associate From the Chair Faculty Staff More Dr. Peter James Jamie Ruth Assistant Professor Administrative Associate A new look and new Catch up on the latest Our talented and Follow along with Field faculty transitions. Here, and greatest from dedicated staff share Camp. See our recent Dr. Scott James Dr. Stacy Atchley shares our esteemed faculty. what's new in their areas— graduates and awards. Assistant Professor what's new with the And meet our newest everything from lab Catch up with our alumni. -

Napoleon and the Cult of Great Men Dissertation

Meteors That Enlighten the Earth: Napoleon and the Cult of Great Men Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Donald Zarzeczny, M.A. Graduate Program in History 2009 Dissertation Committee: Dale K. Van Kley, Advisor Alice Conklin Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Matthew Donald Zarzeczny 2009 Abstract Napoleon promoted and honored great men throughout his reign. In addition to comparing himself to various great men, he famously established a Legion of Honor on 19 May 1802 to honor both civilians and soldiers, including non-ethnically French men. Napoleon not only created an Irish Legion in 1803 and later awarded William Lawless and John Tennent the Legion of Honour, he also gave them an Eagle with the inscription “L’Indépendence d’Irlande.” Napoleon awarded twenty-six of his generals the marshal’s baton from 1804 through 1815 and in 1806, he further memorialized his soldiers by deciding to erect a Temple to the Glory of the Great Army modeled on Ancient designs. From 1806 through 1815, Napoleon had more men interred in the Panthéon in Paris than any other French leader before or after him. In works of art depicting himself, Napoleon had his artists allude to Caesar, Charlemagne, and even Moses. Although the Romans had their legions, Pantheon, and temples in Ancient times and the French monarchy had their marshals since at least 1190, Napoleon blended both Roman and French traditions to compare himself to great men who lived in ancient and medieval times and to recognize the achievements of those who lived alongside him in the nineteenth century.