An Adaptation of Medium Theory Analysis: Youtube As a Digital Moving- Image Medium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

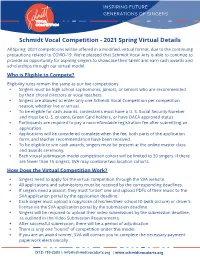

Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details

INSPIRING FUTURE GENERATIONS OF SINGERS VOCAL COMPETITION Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details All Spring 2021 competitions will be offered in a modified, virtual format, due to the continuing precautions related to COVID-19. We’re pleased that Schmidt Vocal Arts is able to continue to provide an opportunity for aspiring singers to showcase their talent and earn cash awards and scholarships through our virtual model. Who is Eligible to Compete? Eligibility rules remain the same as our live competitions: • Singers must be high school sophomores, juniors, or seniors who are recommended by their choral directors or vocal teachers. • Singers are allowed to enter only one Schmidt Vocal Competition per competition season, whether live or virtual. • To be eligible for cash awards, contestants must have a U. S. Social Security Number and must be U. S. citizens, Green Card holders, or have DACA approved status. • Participants are required to pay a non-refundable registration fee after submitting an application. • Applications will be considered complete when the fee, both parts of the application form, and teacher recommendation have been received. • To be eligible to win cash awards, singers must be present at the online master class and awards ceremony. • Each virtual submission model competition cohort will be limited to 30 singers. If there are fewer than 15 singers, SVA may combine two location cohorts. How Does the Virtual Competition Work? • Singers need to apply for the virtual competition through the SVA website. • All applications and submissions must be received by the corresponding deadlines. • If singers need a pianist, they must “order” one and upload PDFs of their music to the SVA application portal by the application deadline. -

Make a Mini Dance

OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Parent Guide Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity children will watch two very short videos online, then create their own mini dances. WHY This activity will get children thinking about the ways their bodies move. They will think about how movements can represent shapes, such as letters in a word. TIME ■ 10–20 minutes RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in kindergarten through 4th grade. GET READY ■ Read Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring together. Ballet for Martha tells the story of three artists who worked together to make a treasured work of American art. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/dance/dance_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Ballet for Martha book (optional) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Open space to move ■ Video camera (optional) ■ Computer with Internet and speakers/headphones More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/dance/. OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Directions, page 1 of 2 For adults and kids to follow together. 1. On May 11, 2011, the Internet search company Google celebrated Martha Graham’s birthday with a special “Google Doodle,” which spelled out G-o-o-g-l-e using a dancer’s movements. Take a look at the video (http://www.google.com/logos/2011/ graham.html). -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

Digital Media Practice and Medium Theory Informing Learning on Mobile Touch Screen Devices

Touching knowledge: Digital media practice and medium theory informing learning on mobile touch screen devices Victor Alexander Renolds Bachelor of Communications (Interactive Multimedia) College of Arts & Education Victoria University. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts 13 November 2017 Abstract The years since 2007 have seen the worldwide uptake of a new type of mobile computing device with a touch screen interface. While this context presents accessible and low cost opportunities to extend the reach of higher education, there is little understanding of how learning occurs when people interact with these devices in their everyday lives. Medium theory concerns the study of one type of media and its unique effects on people and culture (Meyrowitz, 2001, p. 10). My original contribution to knowledge is to use medium theory to examine the effects of the mobile touch screen device (MTSD) on the learning experiences and practices of adults. My research question is: What are the qualities of the MTSD medium that facilitate learning by practice? The aim of this thesis is to produce new knowledge towards enhancing higher education learning design involving MTSDs. The project involved a class of post-graduates studying communications theory who were asked to complete a written major assessment using their own MTSDs. Their assignment submissions form the qualitative data that was collected and analysed, supplemented with field notes capturing my own post-graduate learning experiences whilst using an MTSD. I predominantly focus on the ideas of Marshall McLuhan within the setting of medium theory as my theoretical framework. The methods I use are derived from McLuhan's Laws of the Media (1975), its phenomenological underpinnings and relevance to the concept of ‘flow' (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014b, p. -

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in Youtube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members?

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in YouTube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members? NATALIE MAURER Produced in Thomas Wright’s Spring 2018 ENC 1102 Introduction The LBGTQ community has become a much more prevalent part of today's society. Over the past several years, the LGBTQ community has been recognized more equally in comparison to other groups in society. June 2015 was a huge turning point for the community due to the legalization of same sex marriage. The legalization of same sex marriage in June 2015 had a great impact on the LBGTQ community, as well as non-members. With an increase in new media platforms like YouTube, content on the LGBTQ community has become more accessible and more prevalent than decades ago. LGBTQ media has been represented in movies, television shows, short videos, and even books. The exposure of LQBTQ characters in a popular 2000s sitcom called Will & Grace paved the way for LGBTQ representation in media. A study conducted by Edward Schiappa and others concluded that exposure to LGBTQ communities through TV helped educate Americans, therefore reducing sexual prejudice. Unfortunately, the way the LBGTQ community is portrayed through online media such as YouTube has an effect on LGBTQ members and non-members, and it has yet to be studied. Most “young people's experiences are affected by the present context characterized by the rapidly increasing prevalence of new (online) media” because of their exposure to several media outlets (McInroy and Craig 32). This gap has led to the research question does the LGBTQ representation on YouTube negatively or positively represent this community to its members, and in what way is the community impacted by this representation as well as non- members? One positive way the LGBTQ community was represented through media was on the popular TV show Will & Grace. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

MA JMC CBCSS Syllabus 2019.Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM REGULATIONS & SYLLABUS M A PROGRAMME IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA JMC-CBCSS) FOR AFFILIATED COLLEGES (FROM 2019 ADMISSION) !1 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM PROGRAMME REGULATIONS MASTER OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA-JMC) CBCSS 2019 admission For AFFILIATED Colleges Title of the Programme affiliated Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication ( MA JMC) Duration of the Programme Four semesters with each semester consisting of a minimum of 90 working days distributed over a minimum of 18 weeks, each of 5 working days Eligibility for Admission Candidates who have passed a Bachelor Degree course of the University of Calicut or any other university recognised by the University of Calicut as equivalent thereto and have secured a minimum of 50% marks in aggregate are eligible to apply. However, professional graduates will be considered for admission, provided they secure minimum of first class (60%) in overall subjects. Backward communities and SC/ST candidates will get relaxation in marks as per the university rules. Admission Procedure Admission to the program shall be made in the order of merit of performance of eligible candidates at the entrance examination. The entrance examination will assess the language ability, general knowledge and journalistic aptitude of the candidate. Weightage Marks Holders of PG diploma in journalism 5 marks Graduates with journalism sub 5 marks Three year degree holders with Journalism as Main 7 marks Bachelor’s Degree holders in Multimedia Communication / Visual Communication/ Film Production/Video Production 5 marks Candidates will be given weight age in only one of the categories whichever is higher. -

Integrating New Media and Old Media: Seven Observations Of

The Study Integrating New Media and Old Media: This study examines convergence as Seven Observations of Convergence as a both a concept and a process. I exam- Strategy for Best Practices in Media ine the current state of convergence, Organizations various definitions of convergence, con- vergence practices, and I identify Seven Observations of Convergence to be used as a strategy for best practices in orga- nizations to integrate new and old me- by Gracie Lawson-Borders, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, U.S.A. dia. Everett Rogers’ (1995) diffusion of innovations and the five stages of the innovation process in organizations, coupled with innovation management Introduction land 2001, par. 11). Gentry states by research (Day & Schoemaker 2000; 2001 there were some 50 media part- Murtha, Lenway & Hart 2001; Saksena Convergence is the window of oppor- nerships or affiliations across the U.S. & Hollifield 2002; Wheelwright & Clark tunity for traditional media to align it- practicing convergence, and the lure 1992) are theoretical foundations used self with technologies of the 21st cen- for the media companies ‘is increased to examine the infusion of technologi- tury. The digitization of media and advertising revenue brought about by higher cal change into business practices in information technology and the ensu- ratings, more subscribers, or more website the media industry. The study is based ing transformation of communication traffic’ (Wendland 2001, par. 10). There on research conducted during the sum- media are major contributors to con- is an economic and philosophical du- mer of 2002, and includes excerpts vergence (Gershon 2000; Fidler 1997). ality to the convergence goal for media from more than 36 hours of taped, in- Digital technology compresses infor- organizations that seek to capture depth interviews, participation-obser- mation and allows text, graphics, pho- users and audiences for their online vation field study, and archival docu- tos, and audio to be transmitted effec- and offline business units. -

HOW to MAKE MONEY with Youtube Earn Cash, Market Yourself, Reach Your Customers, and Grow Your Business on the World’S Most Popular Video-Sharing Site

HOW TO MAKE MONEY WITH YouTube Earn Cash, Market Yourself, Reach Your Customers, and Grow Your Business on the World’s Most Popular Video-Sharing Site BRAD AND DEBRA SCHEPP New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by Brad and Debra Schepp. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the pub- lisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-162618-7 MHID: 0-07-162618-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-162136-6, MHID: 0-07-162136-9. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trade- mark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please visit the Contact Us page at www.mhprofessional.com. How to Make Money with YouTube is no way authorized by, endorsed, or affiliated with YouTube or its sub- sidiaries. All references to YouTube and other trademarkedproperties are used in accordance with the Fair Use Doctrine and are not meant to imply that this book is a YouTube product for advertising or other com- mercial purposes.