Digital Media Practice and Medium Theory Informing Learning on Mobile Touch Screen Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Global Media Footprint

February 2021 SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES China’s Global Media Footprint Democratic Responses to Expanding Authoritarian Influence by Sarah Cook ABOUT THE SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES As globalization deepens integration between democracies and autocracies, the compromising effects of sharp power—which impairs free expression, neutralizes independent institutions, and distorts the political environment—have grown apparent across crucial sectors of open societies. The Sharp Power and Democratic Resilience series is an effort to systematically analyze the ways in which leading authoritarian regimes seek to manipulate the political landscape and censor independent expression within democratic settings, and to highlight potential civil society responses. This initiative examines emerging issues in four crucial arenas relating to the integrity and vibrancy of democratic systems: • Challenges to free expression and the integrity of the media and information space • Threats to intellectual inquiry • Contestation over the principles that govern technology • Leverage of state-driven capital for political and often corrosive purposes The present era of authoritarian resurgence is taking place during a protracted global democratic downturn that has degraded the confidence of democracies. The leading authoritarians are ABOUT THE AUTHOR challenging democracy at the level of ideas, principles, and Sarah Cook is research director for China, Hong Kong, and standards, but only one side seems to be seriously competing Taiwan at Freedom House. She directs the China Media in the contest. Bulletin, a monthly digest in English and Chinese providing news and analysis on media freedom developments related Global interdependence has presented complications distinct to China. Cook is the author of several Asian country from those of the Cold War era, which did not afford authoritarian reports for Freedom House’s annual publications, as regimes so many opportunities for action within democracies. -

New Media and Communication”, Chapter 16 from the Book a Primer on Communication Studies (Index.Html) (V

This is “New Media and Communication”, chapter 16 from the book A Primer on Communication Studies (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 16 New Media and Communication As we learned in Chapter 15 "Media, Technology, and Communication", media and communication work together in powerful ways. New technologies develop and diffuse into regular usage by large numbers of people, which in turn shapes how we communicate and how we view our society and ourselves. -

Mass Media in the USA»

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BSU Digital Library Mass Media In The USA K. Khomtsova, V. Zavatskaya The topic of the research is «Mass media in the USA». It is topical because mass media of the United States are world-known and a lot of people use American mass media, especially internet resources. The subject matter is peculiarities of different types of mass media in the USA. The aim of the survey is to study the types of mass media that are popular in the USA nowadays. To achieve the aim the authors fulfill the following tasks: 1. to define the main types of mass media in the USA; 2. to analyze the popularity of different kinds of mass media in the USA; 3. to mark out the peculiarities of American mass media. The mass media are diversified media technologies that are intended to reach a large audience by mass communication. There are several types of mass media: the broadcast media such as radio, recorded music, film and tel- evision; the print media include newspapers, books and magazines; the out- door media comprise billboards, signs or placards; the digital media include both Internet and mobile mass communication. [4]. In the USA the main types of mass media today are: newspapers; magazines; radio; television; Internet. NEWSPAPERS The history of American newspapers goes back to the 17th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. It was James Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, who first made a news sheet. -

Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A

Marquette Law Review Volume 77 | Issue 2 Article 7 Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A. Oswald Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Kristine A. Oswald, Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics, 77 Marq. L. Rev. 385 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol77/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASS MEDIA AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN POLITICS I. INTRODUCTION The importance of the mass media1 in today's society cannot be over- estimated. Especially in the arena of policy-making, the media's influ- ence has helped shape the development of American government. To more fully understand the political decision-making process in this coun- try it is necessary to understand the media's role in the performance of political officials and institutions. The significance of the media's influ- ence was expressed by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: "The Press has become the greatest power within Western countries, more powerful than the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. One would then like to ask: '2 By what law has it been elected and to whom is it responsible?" The importance of the media's power and influence can only be fully appreciated through a complete understanding of who or what the media are. -

MA JMC CBCSS Syllabus 2019.Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM REGULATIONS & SYLLABUS M A PROGRAMME IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA JMC-CBCSS) FOR AFFILIATED COLLEGES (FROM 2019 ADMISSION) !1 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM PROGRAMME REGULATIONS MASTER OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA-JMC) CBCSS 2019 admission For AFFILIATED Colleges Title of the Programme affiliated Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication ( MA JMC) Duration of the Programme Four semesters with each semester consisting of a minimum of 90 working days distributed over a minimum of 18 weeks, each of 5 working days Eligibility for Admission Candidates who have passed a Bachelor Degree course of the University of Calicut or any other university recognised by the University of Calicut as equivalent thereto and have secured a minimum of 50% marks in aggregate are eligible to apply. However, professional graduates will be considered for admission, provided they secure minimum of first class (60%) in overall subjects. Backward communities and SC/ST candidates will get relaxation in marks as per the university rules. Admission Procedure Admission to the program shall be made in the order of merit of performance of eligible candidates at the entrance examination. The entrance examination will assess the language ability, general knowledge and journalistic aptitude of the candidate. Weightage Marks Holders of PG diploma in journalism 5 marks Graduates with journalism sub 5 marks Three year degree holders with Journalism as Main 7 marks Bachelor’s Degree holders in Multimedia Communication / Visual Communication/ Film Production/Video Production 5 marks Candidates will be given weight age in only one of the categories whichever is higher. -

Media Communication (MC) 1

Media Communication (MC) 1 MC 235 (WS 235) Women and Media 3(3-0) MEDIA COMMUNICATION (MC) As Needed. Prerequisite: MC 101. A grade of C or better is required for prerequisite courses. The historical and cultural implications of the mass media's portrayal of women and the extent of their media participation from colonial to MC 101 Media and Society (GT-SS3) 3(3-0) contemporary times. Fall, Spring. Corequisite: None. Prerequisite: None. Survey course that examines the historical, sociological, economic, MC 245 Principles of Audio & Video Production 3(3-0) technological, and ethical foundations of mediated communication from Fall, Spring. a social scientific perspective. Prerequisite: MC 101. Corequisite: None. Concepts, skills, and technology needed for recording and production of digital audio and video communication. (Gen Ed: SS, GT-SS3) Corequisite: None. MC 140 Radio Station Operation 1(1-0) MC 251 Sports Writing and Statistics 3(2-3) Fall, Spring. As Needed. Prerequisite: MC 101. Prerequisite: MC 101. An introduction to radio station operation. Students gain practical Study and practical application of sports writing and statistics; emphasis experience operating KTSC 89.5, Colorado State University Pueblo's 8,000 on press box experience at intercollegiate athletic events. watt radio station. Corequisite: None. MC 211 Digital Publishing 3(1-4) MC 301 Editorial Writing 3(3-0) Spring. As Needed. Prerequisite: MC 101. Prerequisites: MC 101. Introduction to publishing and design principles on a desktop computing Study of editorial page management and policy, with emphasis on environment, preparing students for publication design and editing preparation of editorials, columns and critical reviews. -

Five Principles of New Media: Or, Playing Lev Manovich by Madeleine Sorapure

Five Principles of New Media: Or, Playing Lev Manovich by Madeleine Sorapure Introduction In The Language of New Media, Lev Manovich proposes five “principles of new media”—to be understood “not as absolute laws but rather as general tendencies of a culture undergoing computerization.” The five principles are numerical representation, modularity, automation, variability, and transcoding. I focus on Manovich’s work because I believe it effectively examines the materiality of new media—that is, the influence of the computer’s interface and operations, its logic and ontology, on the production, distribution, and reception of new media. This article offers an interactive explanation and demonstration of the five principles of new media, particularly as they apply to teaching writing, and drawing on work done by students in my Winter 2003 “Writing in New Media” course. Students in the course worked on three projects—two in Photoshop, one in Flash—and they wrote three project reports in which they commented on their own work as well as on theories of new media that we were reading and discussing in class. Text and images are included here with the students’ permission, along with links to some of the Flash projects they composed. The menu to the left allows you to navigate through the article. On all of the screens, you can rollover and/or click on buttons and images to make things happen and to make text visible. Directions at the top of each screen should help you determine how to proceed. 1. Numerical representation Because all new media objects are composed of digital code, they are essentially numerical representations. -

Harold Innis and the Empire of Speed

Review of International Studies (1999), 25, 273–289 Copyright © British International Studies Association Harold Innis and the Empire of Speed RONALD J. DEIBERT* Abstract. Increasingly, International Relations (IR) theorists are drawing inspiration from a broad range of theorists outside the discipline. One thinks of the introduction of Antonio Gramsci’s writings to IR theorists by Robert Cox, for example, and the ‘school’ that has developed in its wake. Similarly, the works of Anthony Giddens, Michel Foucault, and Jurgen Habermas are all relatively familiar to most IR theorists not because of their writings on world politics per se, but because they were imported into the field by roving theorists. Many others of varying success could be cited as well. Such cross-disciplinary excursions are important because they inject vitality into a field that—in the opinion of some at least—is in need of rejuvenation in the face of contemporary changes. In this paper, I elaborate on the work of the Canadian communications theorist Harold Innis, situating his work within contemporary IR theory while underlining his historicism, holism, and attention to time- space biases. Introduction One of the more refreshing developments in recent International Relations (IR) theorizing has been the increasing willingness among scholars to step outside of traditional boundaries to draw from theorists not usually associated with the study of international relations.1 My own expeditions in this respect have been in the communications field, where I have drawn from an approach called ‘medium theory.’ Writers generally associated with this approach, such as Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, Eric Havelock, and Walter Ong, have analysed how different media of communications affect communication content, cognition, and the character of societies.2 In a recent study, I modified and reformulated medium theory to help * An earlier version of this article was delivered to the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 28–31, 1997, Washington, DC. -

Joshua Meyrowitz’S Medium Theory Analyses the Impact of the Electronic Media on Human Behavior in Everyday Life?

Brand 1 Catherine Brand (ID N00185778) Instructor: Jae Kang Media Studies: Ideas Fall 2010 6 October 2010 How does Joshua Meyrowitz’s medium theory analyses the impact of the electronic media on human behavior in everyday life? This paper aims to explain how Joshua Meyrowitz’s medium theory analyses the impact of the electronic media on human behavior in everyday life. It is an attempt to clarify the different ideas that are developed by the author and that ultimately lead to a better comprehension of his theory. To provide a historical context, this paper considers critical research developments conducted by first generation medium theorists Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan. It then focuses on Meyrowitz’s medium theory and its analysis of the impact of electronic media by examining the notions of situations as information systems and roles as information networks. This paper concludes with an evaluation of the theory’s contributions and shortcomings. Before discussing Joshua Meyrowitz’s medium theory it is important to gain an insight into the work of his predecessors, first generation medium theorists Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan. Trained as an economic historian, Harold Innis (1894-1952) draws a parallel between economic monopolies and information monopolies. He argues that the control of media of communication has an impact on changes occurring in a society and on the sustainability of a society. In The Bias of Communication he rewrites the history of Western civilization by placing the innovation of media technology at the center of social and political changes. He observes that a medium of communication has an influence on the dissemination of knowledge and that depending on its characteristics it is either space or time biased. -

Experts Say Conway May Have Broken Ethics Rule by Touting Ivanka Trump'

From: Tyler Countie To: Contact OGE Subject: Violation of Government Ethics Question Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 11:26:19 AM Hello, I was wondering if the following tweet would constitute a violation of US Government ethics: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/829356871848951809 How can the President of the United States put pressure on a company for no longer selling his daughter's things? In text it says: Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump My daughter Ivanka has been treated so unfairly by @Nordstrom. She is a great person -- always pushing me to do the right thing! Terrible! 10:51am · 8 Feb 2017 · Twitter for iPhone Have a good day, Tyler From: Russell R. To: Contact OGE Subject: Trump"s message to Nordstrom Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:03:26 PM What exactly does your office do if it's not investigating ethics issues? Did you even see Trump's Tweet about Nordstrom (in regards to his DAUGHTER'S clothing line)? Not to be rude, but the president seems to have more conflicts of interest than someone who has a lot of conflicts of interests. Yeah, our GREAT leader worrying about his daughters CLOTHING LINE being dropped, while people are dying from other issues not being addressed all over the country. Maybe she should go into politics so she can complain for herself since government officials can do that. How about at least doing your jobs, instead of not?!?!? Ridiculous!!!!!!!!!!!! I guess it's just easier to do nothing, huh? Sincerely, Russell R. From: Mike Ahlquist To: Contact OGE Cc: Mike Ahlquist Subject: White House Ethics Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:23:01 PM Is it Ethical and or Legal for the Executive Branch to be conducting Family Business through Government channels. -

New Social Media and Public Relations: Review of the Medium Theory

NEW SOCIAL MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS: REVIEW OF THE MEDIUM THEORY Oleh Andi Windah Staf Pengajar Jurusan Ilmu Komunikasi FISIP Universitas Lampung ABSTRAK Media telah menjadi bagian yang tak terpisahkan dengan masyarakat. Integrasi ini membawa berbagai perubahan kepada kedua belah pihak mengingat interaksi yang terjalin di antara keduanya. Salah satu perubahan yang mendasar adalah bagaimana media telah membawa sudut pandang baru bagi masyarakat dalam menjalani kehidupannya sehari-hari. Bila dikaji dari sejarah, kondisi ini sebenarnya sudah terjadi sedari media itu ditemukan untuk pertama kalinya. Gagasan bahwa media adalah sebuah lingkungan yang mampu mendorong inovasi bahkan revolusi sebagaimana yang dicetuskan oleh para ahli teori medium. Artikel ini menilik lebih jauh mengenai keberadaan teori medium dengan menggunakan metode studi literatur dan contoh aplikasinya yakni melalui keberadaan media sosial dan implikasi penggunaan media sosial dalam praktek kehumasan. Pendekatan yang digunakan adalah pendekatan praktis dengan menekankan pada pembahasan deskriptif. Dari hasil pembahasan, ditemukan bahwa teori medium berakar pada konsep keberadaan media sebagai sebuah lingkungan yang mampu membawa pengaruh dan perubahan kepada kehidupan manusia. Misalnya aktivitas dalam media sosial semakin mempengaruhi kehidupan di luar media sosial, dengan contoh kasus pemilihan Presiden Barack Obama pada tahun 2008.Kehadiran media sosial juga memciptakan banyak peluang baru bagi praktek di dunia kehumasan, misalnya munculnya profesi kehumasan yang khusus mengelola image perusahaan melalui dunia maya. Kata kunci: media sosial, kehumasan “Facebook has changed me. I remember I once found it difficult to cope with the idea of having a photograph of myself in a public space. I am less private than I used to be” (Golds, 2010) “I tweetedmy opinions on the topics covered in Online Marketing Inside Out book. -

Journalism and Broadcasting

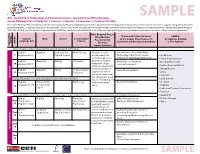

SAMPLE Arts, Audio/Video Technology and Communications: Journalism and Broadcasting Career Pathway Plan of Study for Learners Parents Counselors Teachers/Faculty This Career Pathway Plan of Study (based on the Journalism and Broadcasting Pathway of the Arts, Audio/Video Technology and Communications Career Cluster) can serve as a guide, along with other career planning materials, as learners continue on a career path. Courses listed within this plan are only recommended coursework and should be individualized to meet each learner’s educational and career goals. *This Plan of Study, used for learners at an educational institution, should be customized with course titles and appropriate high school graduation requirements as well as college entrance requirements. Other Required Courses Other Electives *Career and Technical Courses SAMPLE English/ Math Science Social Studies/ Recommended and/or Degree Major Courses for Occupations Relating Language Arts Sciences Journalism and Broadcasting Pathway to This Pathway LEVELS GRADE Electives EDUCATION Learner Activities Interest Inventory Administered and Plan of Study Initiated for all Learners English/ Algebra I Earth or Life or World History All plans of study • Introduction to Arts, Audio/Video 9 Language Arts I Physical Science should meet local Technology and Communications Art Director and state high school • Information Technology Applications Audio-Video Operator graduation require- English/ Geometry Biology U.S. History • Media Arts Fundamentals Broadcast Technician 10 Language Arts