Making a Crisis: a History of Homelessness in Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: a Tour of 1950'S Philadelphia Skid

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: A Tour of 1950’s Philadelphia Skid Row Stephen Metraux [email protected] Article for hiddencityphila.org March 2017 An approach to Philadelphia not soon forgotten is on the beautiful [Benjamin Franklin] Bridge high over the river and the city, followed by Franklin Square – also known as “Bum’s Park.” When a traveler sees a tree-filled square with hundreds of men reclining on park benches or lined up for soup and salvation across the street then he has arrived in Philadelphia. The Health and Welfare Council (HWC) opened their 1952 report “What About Philadelphia’s Skid Row?” with this vignette of a motorist’s first impression of Philadelphia. Coming off the bridge from New Jersey, cars would land on Vine Street at 6th Street, with Franklin Square taking up the southern side of the block and the Sunday Breakfast Mission sitting on the northwest corner. This was the gateway to Skid Row, and, for the next three blocks, Vine Street was its main drag. What follows continues the Skid Row tour that the HWC report started 65 years ago by reconstructing this segment of 1950s Vine Street that now lies buried under its namesake expressway. The HWC report directed Philadelphia’s attention to its Skid Row. Generically, skid row denoted an area, present in larger mid-twentieth century American cities, that originated as a pre-Depression era district of itinerant and near indigent workingmen. As this population aged and dwindled after World War II, these areas retained signature amenities such as cheap hotels, religious missions, and bars, all ensconced by seediness and decay. -

Confronting Sa-I-Gu: Twenty Years After the Los Angeles Riots

【특집】 Confronting Sa-i-gu: Twenty Years after the Los Angeles Riots Edward Taehan Chang (the Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies) Twenty years ago on April 29, Los Angeles erupted and Koreatown cried as it burned. For six-days, the LAPD was missing in action as rioting, looting, burning, and killing devastated the city. The “not guilty” Rodney King verdict ignited anger and frustration felt by South Los Angeles residents who suffered from years of neglect, despair, hopelessness, injustice, and oppression.1) In the Korean American community, the Los Angeles riot is remembered as Sa-i-gu (April 29 in Korean). Korean Americans suffered disproportionately high economic losses as 2,280 Korean American businesses were looted or burned with $400 million in property damages.2) Without any political clout and power in the city, Koreatown was unprotected and left to burn since it was not a priority for city politicians and 1) Rodney King was found dead in his own swimming pool on June 17, 2012, shortly after publishing his autobiography The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption Learning How We Can All Get Along, in April 2012. 2) Korea Daily Los Angeles, May 11, 1992. 2 Edward Taehan Chang the LAPD. For the Korean American community, Sa-i-gu is known as its most important historical event, a “turning point,” “watershed event,” or “wake-up call.” Sa-i-gu profoundly altered the Korean American discourse, igniting debates and dialogue in search of new directions.3) The riot served as a catalyst to critically examine what it meant to be Korean American in relation to multicultural politics and race, economics and ideology. -

East Los Angeles Should Not Be Lumped with the Hollywood Hills, Si

East Los Angeles Should Not Be Lumped with the Hollywood Hills, Si... Subject: East Los Angeles Should Not Be Lumped with the Hollywood Hills, Silver Lake, and Los Feliz! From: Franziska WiƩenstein < Date: Thu, 9 Jun 2011 10:47:52 -0700 To: Commissioners, CiƟzens RedistricƟng Commission 901 P Street, Suite 154-A Sacramento, CA 95814 Commissioners: When you Commissioners were picked, many of us in Los Angeles (and many in the media) were concerned that none of you lived in the City of Los Angeles. We were told not to worry, that you understood the region and would draw fair maps. We’ve also been told, throughout the process, that the era of odd-shaped, gerrymandered districts, featuring odd pairings of communiƟes, were over. Then, in your iniƟal draŌ maps, you proposed a district lumping together the Hollywood Hills, Los Feliz, Silver Lake, and East Los Angeles! To get there, the district lines cross the Los Angeles River and dart around Downtown Los Angeles, making the district as bizarrely shaped as anything the poliƟcians ever drew. It will be extremely difficult for whomever is in elected in that district to represent those communiƟes. Those communiƟes are as different as can be. We, the undersigned, strongly urge you to draw more sensible maps. East Los Angeles (and Lincoln Heights, etc.) should be together with other eastside communiƟes so that residents there can elect a repeƟƟve of their choosing. The communiƟes of Hollywood Hills, Los Feliz, and Silver Lake are not “eastside.” No porƟon of those communiƟes are east of Downtown or east of the Los Angeles River. -

Hoovervilles: the Shantytowns of the Great Depression by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L

Hoovervilles: The Shantytowns of the Great Depression By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L A typical shantytown of the Great Depression in the United States, this one located in a city. Photo: WPA The Great Depression was an economic crisis that began in 1929. Many people had invested money in the stock market and when it crashed they lost much of the money they had invested. People stopped spending money and investing. Banks did not have enough money, which led many people to lose their savings. Many Americans lost money, their homes and their jobs. Homeless Americans began to build their own camps on the edges of cities, where they lived in shacks and other crude shelters. These areas were known as shantytowns. As the Depression got worse, many Americans asked the U.S. government for help. When the government failed to provide relief, the people blamed President Herbert Hoover for their poverty. The shantytowns became known as Hoovervilles. In 1932, Hoover lost the presidential election to Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt created programs that helped lift the U.S. out of the Depression. By the early 1940s, most remaining Hoovervilles were torn down. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 The Great Depression sets in The Great Depression was one of the most terrible events of the 1900s, and led to a huge rise in unemployment. By 1933, 1 out of 4 Americans was out of work. Americans looked to the U.S. government for help. -

[email protected] Sent

Archived: Monday, August 17, 2020 11:18:30 AM From: [email protected] Sent: Sunday, August 16, 2020 9:08:08 PM To: agenda comments; Mark Apolinar Subject: [EXTERNAL] Agenda Comments Response requested: Yes Sensitivity: Normal A new entry to a form/survey has been submitted. Form Name: Comment on Agenda Items Date & Time: 08/16/2020 9:08 pm Response #: 635 Submitter ID: 38307 IP address: 50.46.194.37 Time to complete: 6 min. , 20 sec. Survey Details: Answers Only Page 1 1. Margaret Willson 2. Shoreline 3. (○) Richmond Beach 4. [email protected] 5. 08/17/2020 6. 9(a) 7. Dear Shoreline City Council, I am writing about the low barrier Navigation Center being proposed for the former site of Arden Rehab on Aurora Avenue. I read the "Shoreline Area News" notes from your August 10 meeting, and I saw that many of you have embraced a "Housing First" approach to addressing homelessness. I've always been skeptical of the Housing First philosophy, because homelessness, rather than being a person's primarily problem, is usually a symptom of a deeper problem or problems. Fortuituously, I just this past week learned of a brand new report on Housing First by Seattle's own Christopher Rufo, who is a Visiting Fellow for Domestic Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation. The report presents abundant evidence that Housing First works pretty well at keeping a roof over people's heads, but not so well at healing them and helping them turn their lives around. What does work to actually help people is "Treatment First". -

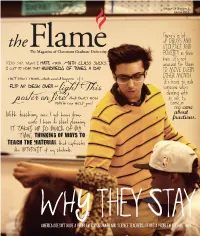

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Cityscape: a Journal of Policy Development and Research • Volume 22, Number 2 • 2020 Cityscape 1 U.S

A Journal of Policy Development and Research TWO ESSAYS ON UNEQUAL GROWTH IN HOUSING VOLUME 22, NUMBER 2 • 2020 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research Managing Editor: Mark D. Shroder Associate Editor: Michelle P. Matuga Advisory Board Dolores Acevedo-Garcia Brandeis University Ira Goldstein The Reinvestment Fund Richard K. Green University of Southern California Mark Joseph Case Western Reserve University Matthew E. Kahn University of California, Los Angeles C. Theodore Koebel Virginia Tech Jens Ludwig University of Chicago Mary Pattillo Northwestern University Carolina Reid University of California Patrick Sharkey New York University Cityscape A Journal of Policy Development and Research Two Essays on Unequal Growth in Housing Volume 22, Number 2 • 2020 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research The goal of Cityscape is to bring high-quality original research on housing and community development issues to scholars, government officials, and practitioners. Cityscape is open to all relevant disciplines, including architecture, consumer research, demography, economics, engineering, ethnography, finance, geography, law, planning, political science, public policy, regional science, sociology, statistics, and urban studies. Cityscape is published three times a year by the Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R) of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Subscriptions are available at no charge and single copies at a nominal fee. The journal is also available on line at huduser.gov/periodicals/cityscape.html. PD&R welcomes submissions to the Refereed Papers section of the journal. Our referee process is double blind and timely, and our referees are highly qualified. -

Btc BETTER TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION 201 N

btc BETTER TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION 201 N. Los Angeles St., Ste.13A 14540 SylvanSt., Ste; A . Los Angeles, CA .90012 · VanNuys, CA 91411 (213} 617-9600 {818) 779~8866 Fa,Y. {213) 517-9643 Fax(818) 779-8870 MAILING AFFIDAVIT City PlanQing Commission Deputy Ad\lisory Agency Case No. ______ Tentative Traer No. ______ Parcel Map No.------~ Zoning Administrator· ·Private Street No. ______ Case No. ______ Coastal Permit Area Planning Commission Case No.-----'-- Central, Harbor, SV, ELA, SLA, WLA, NV Case No.---------- Design Review Board Case No. ______ siTEAC l o~'1 ~oR..~ S'-\~~VY\o~€. ~~~-r- t, _\_·_ &-,.~,-<t· certrfy that I am an employee of BTC ~contractor of the Crty of Los Anqeles. Department of City Planning, State of California, and I drd, on the d.\~ day of ;::::)f'«<v.._y>.Q...'( 20H mail, postage prepaid, to the applicant and all parties required by the Municipal Code,·as detailed on the official ownership list, a notice of hearing, a true copy of which is attached. · .X' 500-foot radius --'---,--Abutting the subject site __,....-"'- __ Owners and Occupants ____ Tenant Notice ____ 100-foot coastal notice --cc,.--State Coastal Commission -~)(-'::--'-. Adjacent City (ies) _ ___!0><'~- Applicant and Representative (where indicated) _city_ Newspaper Notice · X" LA Unified School District, LA County Regional Planning Y Caltrans --;:---,--- Council's Own Initiative __Y~-- Metropolitan Transit Authority -~><'2?--- Certified Neighborhood Council (dept of Neighborhood Empowerment) X Council Office and Council District Office _city_ Homeowners Associations >< Other \)~ (:%: \?W:: Ll) Z:)J (:::> 'T &r->.~'E:,"('{ There is a regular daily communication and service by mail between the City of Los Angeles and each of the A~J: ~were mailed. -

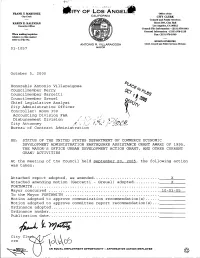

Community and Economic Development Committee Report (Item No

~' ,,. u '•' ,,.,.,,,.,1.i!,,.: ,, , •• 0 ~Ef¥' OF' Los, ANGEL:: Office of the FRANK T. MARTINEZ .. , , CALIFORNIA L City Clerk CITY CLERK Council and Public Services KAREN E. KALFAYAN Room 395, City Hall Executive Officer Los Angeles, CA 90012 Council File Information - (213) 978-1043 General Information - (213) 978-1133 When making inquiries Fax: (213) 978-1040 relative to this matter refer to File No. HELEN GINSBURG ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA Chief, Council and Public Services Division 01-1057 MAYOR October 5, 2005 Honorable Antonio Villaraigosa Councilmember Perry. Councilmember Garcetti Councilmember Greuel Chief Legislative Analyst City Administrative Officer Controller: Room 300 Accounting Division F&A ~- Disbursement Division , City Attorney / ~. Bureau of Contract Administr~tion RE: STATUS OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ADMINISTRATION EARTHQUAKE ASSISTANCE GRANT AWARD OF 1995, THE MAYOR'S OFFICE URBAN DEVELOPMENT ACTION GRANT, AND OTHER CURRENT GRANT ACTIVITIES I At the meeting of the Council held September 20, 2005, the following action was taken: Attached report adopted, as amended............................ X Attached amending motion (Garcetti - Greuel) adopted........... X 'FORTHWITH ..................................................... ·------- Mayor concurred . 10-03-05 To the Mayor FORTHWITH ........................................ ______ Motion adopted to approve communication recommendation(s) ..... ·~~~~~~- Motion adopted to approve committee report recommendation(s) .. ·~~~~~~- _Ordinance adopted ............................................ ··~~~~~~- Ordinance number .............................................. ·~~~--~~- Publication date .............................................. ·~~~~~~- ~ ft >'Y/~ City crm \o\1o\0S AN EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY-AFFIRMATIVE ACTION EMPLOYER City Clerk '/~[GEJ.~~) Stamp CITY O EPi<;::; OFFICE 2005 SEP 22 PM ~: 09 Zill5 SEP ?2 Pii q: 07 CIT y PF LOS I~ NGELES CITY r:[~ ___P"°''/ rit\ PV L) ! -----=o=Ep=u-=T~Y SUBJECT TO MAYOR'S APPROVAL COUNCIL FILE NO. -

New Deal for Housing Justice: a Housing Playbook for the New

New Deal for Housing Justice A Housing Playbook for the New Administration JANUARY 2021 About this Publication New Deal for Housing Justice is the result of the input, expertise, and lived experience of the many collaborators who participated in the process. First and foremost, the recommendations presented in this document are rooted in the more than 400 ideas shared by grassroots leaders and advocates in response to an open call for input launched early in the project. More than 100 stakeholder interviews were conducted during the development of the recommendations, and the following people provided external review: Afua Atta-Mensah, Rebecca Cokley, Natalie Donlin-Zappella, Edward Golding, Megan Haberle, Priya Jayachandran, Richard Kahlenberg, Mark Kudlowitz, Sunaree Marshall, Craig Pollack, Vincent J. Reina, Sherry Riva, Heather Schwartz, Thomas Silverstein, Philip Tegeler, and Larry Vale. Additional information is available on the companion website: http://www.newdealforhousingjustice.org/ Managing Editor Lynn M. Ross, Founder and Principal, Spirit for Change Consulting Contributing Authors Beth Dever, Senior Project Manager, BRicK Partners LLC Jeremie Greer, Co-Founder/Co-Executive Director, Liberation in a Generation Nicholas Kelly, PhD Candidate, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Rasmia Kirmani-Frye, Founder and Principal, Big Urban Problem Solving Consulting Lindsay Knotts, Independent Consultant and former USICH Policy Director Alanna McCargo, Vice President, Housing Finance Policy Center, Urban Institute Ann Oliva, Visiting -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Governing Urban School Districts: Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Education View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Governing Urban School Districts Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect Change Catherine H. Augustine, Diana Epstein, Mirka Vuollo The research described in this report was conducted within RAND Education for the Presidents' Joint Commission on LAUSD Governance.