Genetic Influences on Craving for Alcohol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tursiops Truncatus): ESTABLISHMENT of NOVEL MOLECULAR TOOLS to STUDY MARINE MAMMALS in CHANGING ENVIRONMENTS

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BOLOGNA Facoltà di Scienze Matematiche Fisiche e Naturali Scuola di Dottorato in Scienze Biologiche, Biomediche e Biotecnologiche Dottorato di Ricerca in Biologia e Fisiologia Cellulare Ciclo XXII SSD: BIO/11 FUNCTIONAL GENOMICS AND CELL BIOLOGY OF THE DOLPHIN (Tursiops truncatus): ESTABLISHMENT OF NOVEL MOLECULAR TOOLS TO STUDY MARINE MAMMALS IN CHANGING ENVIRONMENTS Presentata da: Dott.ssa ANNALAURA MANCIA Coordinatore Dottorato: Relatore: Prof.ssa Michela Rugolo Prof.ssa Marialuisa Melli - Esame finale 2010 - ALMA MATER STUDIORUM UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BOLOGNA Faculty of Science Physiology and Cellular Biology XXII PhD Program SSD: BIO/11 FUNCTIONAL GENOMICS AND CELL BIOLOGY OF THE DOLPHIN (Tursiops truncatus): ESTABLISHMENT OF NOVEL MOLECULAR TOOLS TO STUDY MARINE MAMMALS IN CHANGING ENVIRONMENTS PhD Student: Dr ANNALAURA MANCIA Program Coordinator: Supervisor: Michela Rugolo, PhD Marialuisa Melli, PhD - Final PhD exam 2010 - To my sister, Roberta, once again “Dolphins are ‘non-human persons’ who qualify for moral standing as individuals” Thomas White “Research is what I'm doing when I don't know what I'm doing” Wernher Von Braun ABSTRACT The dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) is a mammal that is adapted to life in a totally aquatic environment. Despite the popularity and even iconic status of the dolphin, our knowledge of its physiology, its unique adaptations and the effects on it of environmental stressors are limited. One approach to improve this limited understanding is the implementation of established cellular and molecular methods to provide sensitive and insightful information for dolphin biology. We initiated our studies with the analysis of wild dolphin peripheral blood leukocytes, which have the potential to be informative of the animal’s global immune status. -

A Dissertation Entitled the Androgen Receptor

A Dissertation entitled The Androgen Receptor as a Transcriptional Co-activator: Implications in the Growth and Progression of Prostate Cancer By Mesfin Gonit Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree in Biomedical science Dr. Manohar Ratnam, Committee Chair Dr. Lirim Shemshedini, Committee Member Dr. Robert Trumbly, Committee Member Dr. Edwin Sanchez, Committee Member Dr. Beata Lecka -Czernik, Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2011 Copyright 2011, Mesfin Gonit This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of The Androgen Receptor as a Transcriptional Co-activator: Implications in the Growth and Progression of Prostate Cancer By Mesfin Gonit As partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree in Biomedical science The University of Toledo August 2011 Prostate cancer depends on the androgen receptor (AR) for growth and survival even in the absence of androgen. In the classical models of gene activation by AR, ligand activated AR signals through binding to the androgen response elements (AREs) in the target gene promoter/enhancer. In the present study the role of AREs in the androgen- independent transcriptional signaling was investigated using LP50 cells, derived from parental LNCaP cells through extended passage in vitro. LP50 cells reflected the signature gene overexpression profile of advanced clinical prostate tumors. The growth of LP50 cells was profoundly dependent on nuclear localized AR but was independent of androgen. Nevertheless, in these cells AR was unable to bind to AREs in the absence of androgen. -

Algorithms and Applications of Next-Generation DNA Sequencing

Algorithms and Applications of Next-Generation DNA Sequencing Chip-Seq, database of human variations, and analysis of mammary ductal carcinomas by Anthony Peter Fejes Bachelor of Science, Biochemistry (Hons. Co-op), University of Waterloo, 2000 Bachelor of Independent Studies, University of Waterloo, 2001 Master of Science, Microbiology & Immunology, The University of British Columbia, 2004 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Bioinformatics) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) April 2012 © Anthony Peter Fejes, 2012 Abstract Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies enable Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) or Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) sequencing to be done at volumes and speeds several orders of magnitude faster than Sanger (dideoxy termination) based methods and have enabled the development of novel experiment types that would not have been practical before the advent of the NGS-based machines. The dramatically increased throughput of these new protocols requires significant changes to the algorithms used to process and analyze the results. In this thesis, I present novel algorithms used for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and Sequencing (ChIP-Seq) as well as the structures required and challenges faced for working with Single Nucleotide Variations (SNVs) across a large collection of samples, and finally, I present the results obtained when performing an NGS based analysis of eight mammary ductal carcinoma cell lines and four matched normal cell lines. ii Preface The work described in this thesis is based entirely upon research done at the Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre (BCGSC) in Dr. Steve J.M. Jones’ group by Anthony Fejes. -

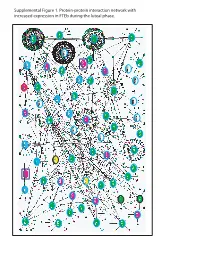

Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-Protein Interaction Network with Increased Expression in Fteb During the Luteal Phase

Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-protein interaction network with increased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Supplemental Figure 2. Protein-protein interaction network with decreased expression in FTEb during luteal phase. LEGENDS TO SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-protein interaction network with increased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Submission of probe sets differentially expressed in the FTEb specimens that clustered with SerCa as well as those specifically altered in FTEb luteal samples to the online I2D database revealed overlapping networks of proteins with increased expression in the four FTEb samples and/or FTEb luteal samples overall. Proteins are represented by nodes, and known and predicted first-degree interactions are represented by solid lines. Genes encoding proteins shown as large ovals highlighted in blue were exclusively found in the first comparison (Manuscript Figure 2), whereas those highlighted in red were only found in the second comparison (Manuscript Figure 3). Genes encoding proteins shown as large ovals highlighted in black were found in both comparisons. The color of each node indicates the ontology of the corresponding protein as determined by the Online Predicted Human Interaction Database (OPHID) link with the NAViGaTOR software. Supplemental Figure 2. Protein-protein interaction network with decreased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Submission of probe sets differentially expressed in the FTEb specimens that clustered with SerCa as well as those specifically altered in FTEb luteal samples to the online I2D database revealed overlapping networks of proteins with decreased expression in the four FTEb samples and/or FTEb luteal samples overall. Proteins are represented by nodes, and known and predicted first-degree interactions are represented by solid lines. -

For Almost Three Decades Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 2(HTLV-2)

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE HUMAN T-CELL LEUKEMIA VIRUS TYPE-2 P28 ACCESSORY PROTEIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rami Doueiri MSc. Graduate Program in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Patrick L. Green, Advisor Dr. Mamuka Kvaratskhelia Dr. Michael Oglesbee Dr. David Bisaro Copyright by Rami Doueiri 2012 ABSTRACT Human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1 (HTLV-1) was the first identified human retrovirus that causes malignancy, and further research identified it as the etiological agent of several neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases. On the other hand, HTLV-2, which shares high sequence and structural homology with HTLV-1, is less pathogenic with few reported cases of neurodegenerative diseases. HTLVs encode structural and enzymatic proteins, Gag, Pro and Env, regulatory proteins, Tax and Rex and several accessory genes required for in vivo viral persistence. Extensive comparative studies of the regulatory genes elucidated the role of these proteins in the viral life cycle and in part explained the different pathology of both viruses. However, increasing amount of evidence describes an essential role for the accessory genes in the viral pathogenic process. p30 and p28 are two accessory proteins encoded by HTLV-1 and HTLV-2, respectively. p30 and p28 are encoded from the second open reading frame (ORF-II) and share some amino acid homology. They are post-transcriptional negative regulators of viral replication, and act by retaining tax/rex mRNA in the nucleus. However, unlike p30, p28 is devoid of transcriptional activity. -

A System for Enhancing Genome-Wide Coexpression Dynamics Study

A system for enhancing genome-wide coexpression dynamics study Ker-Chau Li†‡, Ching-Ti Liu, Wei Sun, Shinsheng Yuan†, and Tianwei Yu Department of Statistics, 8125 Mathematical Sciences Building, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1554 Edited by Michael S. Waterman, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, and approved August 30, 2004 (received for review April 28, 2004) Statistical similarity analysis has been instrumental in elucidation mRNA level. Yet a third possibility can be described in terms of LA. of the voluminous microarray data. Genes with correlated expres- This more advanced concept of statistical association originates sion profiles tend to be functionally associated. However, the from the need to describe a situation as schematized in Fig. 1 Left, majority of functionally associated genes turn out to be uncorre- wherein two opposing trends between X and Y are displayed. The lated. One conceivable reason is that the expression of a gene can positive and negative correlations cancel each other out, rendering be sensitively dependent on the often-varying cellular state. The the overall correlation insignificant. It would be valuable to learn intrinsic state change has to be plastically accommodated by why and how the change of trend occurs. But for real data, such gene-regulatory mechanisms. To capture such dynamic coexpres- hidden trends are not easy to detect directly from the scatterplot of sion between genes, a concept termed ‘‘liquid association’’ (LA) has X and Y. To alleviate the difficulty, we look for additional variables been introduced recently. LA offers a scoring system to guide a that may be associated with the change of the trend. -

Molecular Karyotypes of Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg Cells at Disease Onset Reveal Distinct Copy Number Alterations in Chemosensitive Versus Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma

Published OnlineFirst March 8, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1071 Clinical Cancer Predictive Biomarkers and Personalized Medicine Research Molecular Karyotypes of Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg Cells at Disease Onset Reveal Distinct Copy Number Alterations in Chemosensitive versus Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma Marilyn L. Slovak1, Victoria Bedell1, Ya-Hsuan Hsu1, Dolores B. Estrine1, Norma J. Nowak5, Maria L. Delioukina2, Lawrence M. Weiss3, David D. Smith, and Stephen J. Forman2 Abstract Purpose: To determine the recurring DNA copy number alterations (CNA) in classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) using laser capture þ microdissected CD30 Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg (HRS) cells. þ Experimental Design: Archived tissues from 27 CD30 HL plus control samples were analyzed by DNA microarrays. The HL molecular karyotypes were compared with the genomic profiles of germinal center B cells and treatment outcome (chemotherapy responsive vs. primary refractory disease). Results: Gains and losses observed in more than 35% of HL samples were localized to 22 and 12 chromosomal regions, respectively. Frequent gains (>65%) were associated with growth and proliferation, NF-kB activation, cell-cycle control, apoptosis, and immune and lymphoid development. Frequent losses (>40%) observed encompassed tumor suppressor genes (SPRY1, NELL1,andID4, inhibitor of DNA binding 4), transcriptional repressors (TXNIP, thioredoxin interacting protein), SKP2 (S-phase kinase-associated protein 2; ubiquitin ligase component), and an antagonist of NF-kB activation (PPARGC1A). In comparison to the germinal center profiles, the most frequent imbalances in HL were losses in 5p13 (AMACR, GDNF, and SKP2), and gains in 7q36 (SHH, sonic hedgehog homolog) and 9q34 (ABL1, CDK9, LCN2, and PTGES). -

Byrne, Enda, G

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Byrne, Enda, Gehrman, Philip, Medland, Sarah, Nyholt, Dale, Heath, An- drew, Madden, Pamela, Hickie, Ian, van Duijn, Cornelia, Henders, Anjali, Montgomery, Grant, Martin, Nicholas, & Wray, Naomi (2013) A genome-wide association study of sleep habits and insomnia. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 162(5), pp. 439-451. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/91833/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32168 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. -

Affymetrix Probe ID Gene Symbol 1007 S at DDR1 1494 F At

Affymetrix Probe ID Gene Symbol 1007_s_at DDR1 1494_f_at CYP2A6 1552312_a_at MFAP3 1552368_at CTCFL 1552396_at SPINLW1 /// WFDC6 1552474_a_at GAMT 1552486_s_at LACTB 1552586_at TRPV3 1552619_a_at ANLN 1552628_a_at HERPUD2 1552680_a_at CASC5 1552928_s_at MAP3K7IP3 1552978_a_at SCAMP1 1553099_at TIGD1 1553106_at C5orf24 1553530_a_at ITGB1 1553997_a_at ASPHD1 1554127_s_at MSRB3 1554152_a_at OGDH 1554168_a_at SH3KBP1 1554217_a_at CCDC132 1554279_a_at TRMT2B 1554334_a_at DNAJA4 1554480_a_at ARMC10 1554510_s_at GHITM 1554524_a_at OLFM3 1554600_s_at LMNA 1555021_a_at SCARF1 1555058_a_at LPGAT1 1555197_a_at C21orf58 1555282_a_at PPARGC1B 1555460_a_at SLC39A6 1555559_s_at USP25 1555564_a_at CFI 1555594_a_at MBNL1 1555729_a_at CD209 1555733_s_at AP1S3 1555906_s_at C3orf23 1555945_s_at FAM120A 1555947_at FAM120A 1555950_a_at CD55 1557137_at TMEM17 1557910_at HSP90AB1 1558027_s_at PRKAB2 1558680_s_at PDE1A 1559136_s_at FLJ44451 /// IDS 1559490_at LRCH3 1562378_s_at PROM2 1562443_at RLBP1L2 1563522_at DDX10 /// LOC401533 1563834_a_at C1orf62 1566509_s_at FBXO9 1567214_a_at PNN 1568678_s_at FGFR1OP 1569629_x_atLOC389906 /// LOC441528 /// LOC728687 /// LOC729162 1598_g_at GAS6 /// LOC100133684 200064_at HSP90AB1 200596_s_at EIF3A 200597_at EIF3A 200604_s_at PRKAR1A 200621_at CSRP1 200638_s_at YWHAZ 200640_at YWHAZ 200641_s_at YWHAZ 200702_s_at DDX24 200742_s_at TPP1 200747_s_at NUMA1 200762_at DPYSL2 200872_at S100A10 200878_at EPAS1 200931_s_at VCL 200965_s_at ABLIM1 200998_s_at CKAP4 201019_s_at EIF1AP1 /// EIF1AX 201028_s_at CD99 201036_s_at HADH -

Genome-Wide Characterization of Phytophthora Infestans 47 Metabolism: a Systems Biology Approach

Uncovering oomycete metabolism using systems biology Sander Y.A. Rodenburg Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr F.P.M. Govers Personal chair at the Laboratory of Phytopathology Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr D. de Ridder Professor of the Bioinformatics Group Wageningen University & Research Co-promotors Dr M.F. Seidl Assistant Professor, Theoretical Biology & Bioinformatics Utrecht University Other members Prof. Dr J.M. Wells, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr J.M. McDowell, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg CA, USA Prof. Dr V. van Noort, Leiden University Dr M. Suarez Diez, Wageningen University & Research This work was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School Experimental Plant Sciences. Uncovering oomycete metabolism using systems biology Sander Y.A. Rodenburg Thesis submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 15 September at 16:00 p.m. in the Aula Sander Y.A. Rodenburg Uncovering oomycete metabolism using systems biology 174 pages PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands (2020) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN: 978-94-6395-494-5 DOI: 10.18174/528798 Table of contents Chapter 1 General introduction 7 Chapter 2 Oomycete metabolism is highly dynamic and reflects lifestyle 17 adaptations Chapter 3 Genome-wide characterization of Phytophthora infestans -

Deriving a Refined Set of Housekeeping Genes in Differentiating Human Embryonic Stem Cells Ida Paramonov

Deriving a refined set of housekeeping genes in differentiating human embryonic stem cells Ida Paramonov Masters Degree in Bioinformatics School of Humanities and Informatics University of Skövde 2008 Academic supervisor: Jane Synnergren Deriving a refined set of housekeeping genes in differentiating human embryonic stem cells Submitted by Ida Paramonov to the University of Skövde as a dissertation towards the degree of M.Sc. by examination and dissertation in the School of Humanities and Informatics. February 2008 I hereby certify that all material in this dissertation which is not my own work has been identified and that no material is included for which a degree has already been conferred upon me. ______________________ (Ida Paramonov ) 2 Abstract In this thesis project housekeeping genes in differentiating human embryonic stem cells were investigated. Housekeeping genes are involved in basic functions in the cells and are assumed to be expressed at relatively constant levels across different cell types and experimental conditions. Based on these features, housekeeping genes are frequently used as controls in calibration of gene expression data. Commonly used housekeeping genes in somatic tissues have shown to vary notably in human embryonic stem cells and are therefore inappropriate as reference genes in this unique cell type. In the present work a novel set of gene expression data obtained by profiling of undifferentiated and early differentiating cardiac cells, was analyzed. Stably expressed genes were identified in this data set and were subsequently intersected with a previously proposed set of 292 stable genes in human embryonic stem cells. A resulting set of 73 genes show stability across all investigated cell lines and experimental conditions. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Rozenblatt-Rosen et al. 10.1073/pnas.0812023106 SI Text mix (4304437; Applied Biosystems), an ABI Prism 7700 instru- Antibodies. The following antibodies were generated by Bethyl ment (Applied Biosystems), and the following Assays-on- Laboratories: anti-Cdc73 Ab648 (BL648, A300–170A) and Demand (Applied Biosystems): CDC73 (Hs00225998m1), Ab649 (BL649, A300–171A), anti-CPSF-160 (BL1896), anti- INTS6 (Hs00247179m1), and ACTB (4310879E), which was CPSF-100 (BL1902), anti-CPSF-73 (BL1906), anti-CPSF-30 used as an internal reference standard. For detecting INTS6 (BL1985), anti-CstF-77 (BL1894), anti-CstF-64 (BL1889), and read-through transcripts, real-time PCR quantitation was per- anti-Ints6 (BL1115). Normal rabbit IgG was obtained from formed in triplicate by using SYBR green PCR Master Mix Bethyl Laboratories. Other antibodies were obtained commer- (4309155; Applied Biosystems), and the primer pairs whose cially as follows: anti-symplekin antibodies (BD Bioscience), sequence is detailed below. GAPDH (43088313; Applied Bio- anti-RNA polymerase II antibodies (Covance), anti-histone H3 systems) was used as an internal reference standard. For deter- tri methyl K4 (Abcam), and anti-histone H3 tri methyl K36 mining transcript levels the standard curve method for relative (Upstate and Millipore). Antibodies were diluted in 5% milk/ quantitation was used. TBST according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A ReliaBlot kit (Bethyl Labratories) was used to avoid masking of protein RNA Expression Analysis. Expression levels were measured in 4 bands by the Ig heavy chain. replicates for each of the 2 CDC73 siRNAs, for a total of 8 test samples. These were invariant-set normalized together with 8 Immunopurification and Mass Spectrometry.