Xinjiang's Militarized Vocational Training System Comes to Tibet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Projects in Tibetan Areas of China: Articulating Clear Goals and Achieving Sustainable Results

DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN TIBETAN AREAS OF CHINA: ARTICULATING CLEAR GOALS AND ACHIEVING SUSTAINABLE RESULTS ROUNDTABLE BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 19, 2004 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 93–221 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:20 Apr 26, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 93221.TXT China1 PsN: China1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JIM LEACH, Iowa, Chairman CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska, Co-Chairman DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming DAVID DREIER, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas FRANK WOLF, Virginia PAT ROBERTS, Kansas JOE PITTS, Pennsylvania GORDON SMITH, Oregon SANDER LEVIN, Michigan MAX BAUCUS, Montana MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio CARL LEVIN, Michigan SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California DAVID WU, Oregon BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State GRANT ALDONAS, Department of Commerce LORNE CRANER, Department of State JAMES KELLY, Department of State STEPHEN J. LAW, Department of Labor JOHN FOARDE, Staff Director DAVID DORMAN, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:20 Apr 26, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 93221.TXT China1 PsN: China1 C O N T E N T S Page STATEMENTS Miller, Daniel, agricultural officer, U.S. -

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Tibet Brief October 2020 a Report of the International Campaign for Tibet

TIBET BRIEF OCTOBER 2020 A REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET NEW REPORT REVEALS COERCIVE LABOR PROGRAM IN TIBET IN THIS ISSUE 1 New report reveals coercive labor program in Tibet 2 Tibet raised at EU-China leaders’ virtual meeting 3 China elected to UN Human Rights Council but suffers another setback as criticism grows 4 ICT joins Global Day of Action against human Military-style training of “rural surplus laborers” in the Chamdo region of Tibet in 2016. (Photo: Tibet’s Chamdo, 30 June 2016). rights violations in China 5 Seventh Tibet Work Forum MIRRORING A PROGRAM OF FORCED LABOR IN XINJIANG, BEIJING IS promises more repression PUSHING GROWING NUMBERS OF TIBETANS INTO MILITARY-STYLE "TRAINING CENTERS", WHERE THEY ARE BEING TURNED INTO LOW- 6 Arrest of New York police PAID FACTORY WORKERS, A NEW REPORT HAS FOUND. officer accused of spying The report, released on 22 September of the TAR last year, includes a number for China reveals China’s by the Jamestown Foundation and of racist assumptions about Tibetans’ efforts against Tibetans corroborated by Reuters, documents “backwardness” and the need to reform their abroad a large-scale program in the Tibet thinking and cultural identity while making New ICT report exposes Autonomous Region (TAR) that pushed them loyal to the Chinese Communist 7 more than half a million rural Tibetans off Party. It also seeks to reduce the influence fraudulent “anti-gang” trial their land and into military-style training of Tibetans’ Buddhist religion, and to force of “Sangchu 10” Tibetans centers in the first seven months of this Tibetans to abandon their traditional way of Political Prisoner Focus year alone. -

2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution, which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, states that citizens have freedom of religious belief but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” and does not define “normal.” Despite Chairman Xi Jinping’s decree that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists,” the government continued to exercise control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to the five state- sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. There were several reports of individuals committing suicide in detention, or, according to sources, as a result of being threatened and surveilled. In December Pastor Wang Yi was tried in secret and sentenced to nine years in prison by a court in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, in connection to his peaceful advocacy for religious freedom. -

Educating the Heart

Approaching Tibetan Studies About Tibet Geography of Tibet Geographical Tibet Names: Bod (Tibetan name) Historical Tibet (refers to the larger, pre-1959 Tibet, see heavy black line marked on Tibet: A Political Map) Tibet Autonomous Region or Political Tibet (refers to the portion of Tibet named by People’s Republic of China in 1965, see bolded broken line on Tibet: A Political Map) Khawachen (literary Tibetan name meaning “Abode of Snows”) Xizang (the historical Chinese name for meaning “Western Treasure House”) Land of Snows (Western term) Capital: Lhasa Provinces: U-Tsang (Central & Southern Tibet) Kham (Eastern Tibet) Amdo (Northeastern Tibet) Since the Chinese occupation of Tibet, most of the Tibetan Provinces of Amdo and Kham have been absorbed into the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan Main Towns: Llasa, Shigatse, Gyantse, Chamdo Area: 2,200,000 Sq. kilometers/850,000 sq. miles Elevation: Average 12-15,000 feet Tibet is located on a large plateau called the Tibetan Plateau. Borders: India, Nepal, Bhutan, Burma (south) China (west, north, east) Major Mountains Himalaya (range to south & west) and Ranges Kunlun (range to north) Chomolungma (Mt. Everest) 29,028 ft. Highest peak in the world Kailas (sacred mountain in western Tibet to Buddhists, Hindus & Jains) The Tibetan Plateau is surrounded by some of the world’s highest mountain ranges. Major Rivers: Ma Chu (Huzng He/Yellow Dri Chu (Yangtze) Za Chu (Mekong) Ngul Chu (Salween) Tsangpo (Bramaputra) Ganges Sutlej Indus Almost all of the major rivers in Asia have their source in Tibet. Therefore, the ecology of Tibet directly impacts the ecology of East, Southeast and South Asia. -

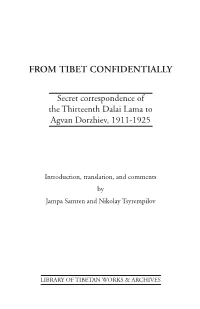

From Tibet Confidentially

FROM TIBET CONFIDENTIALLY Secret correspondence of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to Agvan Dorzhiev, 1911-1925 Introduction, translation, and comments by Jampa Samten and Nikolay Tsyrempilov LIBRARY OF TIBETAN WORKS & ARCHIVES Copyright © 2011 Jampa Samten and Nikolay Tsyrempilov First print: 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-93-80359-49-6 Published by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P. 176215, and printed at Indraprastha Press (CBT), Nehru House, New Delhi-110002 To knowledgeable Tsenshap Khenché Lozang Ngawang (Agvan Dorzhiev) Acknowledgement V We gratefully acknowledge the National Museum of Buriatia that kindly permitted us to copy, research, and publish in this book the valuable materials they have preserved. Our special thanks is to former Director of the Museum Tsyrenkhanda Ochirova for it was she who first drew our attention to these letters and made it possible to bring them to light. We thank Ven. Geshe Ngawang Samten and Prof. Boris Bazarov, great enthusiasts of collaboration between Buriat and Tibetan scholars of which this book is not first result. We are grateful to all those who helped us in our work on reading and translation of the letters: Ven. Beri Jigmé Wangyel for his valuable consultations and the staff of the Central University of Tibetan Studies Ven. Ngawang Tenpel, Tashi Tsering, Ven. Lhakpa Tsering for assistance in reading and interpretation of the texts. We express our particular gratitude to Tashi Tsering (Director of Amnye Machen Institute, Tibetan Centre for Advanced Studies, Dharamsala) for his valuable assistance in identification of the persons on the Tibetan delegation group photo published in this book. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Tashi Nyima Citation

Historical relationship among three non-Tibetic languages in Title Chamdo, TAR Author(s) Suzuki, Hiroyuki; Tashi Nyima Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235308 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Historical relationship among three non-Tibetic languages in Chamdo, TAR Hiroyuki Suzuki Tashi Nyima (IKOS, Universitetet i Oslo) (The Evolution Institute) 1 Introduction Chamdo Municipality is located in the east of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Three counties in this municipality have at least three non-Tibetic, yet Tibeto-Burman language islands surrounded by various dialect groups of Khams Tibean, i.e.: • Lamo: Spoken in the west of Dzogang County, along the Nujiang River. • Larong sMar : Spoken along the Lancangjiang River of Dzogang and sMarkhams County. • Drag-yab sMar : Spoken in the southern half of Drag-yab County. Changdu Diquzhi (2005:819) mentions three special dialect s (Dongba, Rumei, and Zesong) within Chamdo, which correspond to the three languages above. Designed with ArcGIS Online See Tashi Nyima and Suzuki (forthcoming) for more detailed information of the geographical distribution and sociolinguistic background of each language. Our previous descriptions (Suzuki & Tashi Nyima 2016, 2017) primarily discussed the case of Lamo, and did not pay special attention to the two other languages. This article examines whether these three languages are mutually related, if so, how they are related. For this purpose, it attempts to outline a historical context to the languages and their speakers, including a brief cultural history of the language territories. -

15 Days Sichuan-Tibet Hwy Northern Route Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 15 days Sichuan-Tibet Hwy northern route tour https://windhorsetour.com/sichuan-yunnan-tibet-tour/sichuan-tibet-hwy-northern-route-tour Chengdu Kangding Ganzi Dege Chamdo Tengchen Nagqu Namtso Lhasa The longest and most diverse overland tour we offer, travel along the Sichuan Tibet northern highway on an adventure that takes you closer to the people, and their lifestyle than anything else. Type Private Duration 15 days Theme Overland Trip code WT-405 Price From ¥ 14,600 per person Itinerary This is one of the two main routes of Sichuan-Tibet Highway which links the Tibetan areas of Western Sichuan with mainland Tibet. This route is longer than the southern route but less affected by rain during summer. The journey goes through the wild, mountainous and remote Tibetan areas of Western Sichuan, you will be amazed to see that Tibetan culture is in many ways better preserved here. The route offers an insight to the rich culture, costume and tradition of Khampa people and their lifestyle, monasteries are unavoidable part of their day to day life and from there you will feel their faith in religion. Moreover, the high altitude grasslands in the northern area is the home for thousands of Tibetan nomads and their animals, the black and short yak wool made nomads tents are can be visited if there are not far from the road. This journey could be very tough and challenging, due to its geographical remoteness and poor infrastructure and facilities. (Note: Due to the closure of Chamdo - the capital city of Chamdo Prefecture to foreign tourists, this travel route is not available currently. -

Copy of TCHRD August 2019 Digest

M A R C H 2 0 2 0 Monthly Translation and Analyses Digest A compilation of selected stories, translation and analyses of Chinese government media reports that are otherwise available only in Chinese and Tibetan language. Front page image: A Tibetan nomad in Tsonyi County, Nagchu Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region, 30 January 2019. (Xinhua/Purbu Zhaxi) In this issue China's nomad relocation plan displaces more than 130000 Tibetans China's nomad in TAR relocation plan displaces more than Chinese authorities in Tibet Autonomous Region 130000 Tibetans in (TAR) have announced that the Ecological TAR Relocation Plan (2018-2025) for extremely high altitude areas of more than 4,800 meters in Nagchu (Ch: Naqu), Ngari (Ch: Ali), and Shigatse Chinese cadres and (Ch: Xigaze) cities, which will result in the relocation migrants resume work at of more than 130,000 people living in 20 counties, Tibet dam amid 97 townships, and 450 villages, out of which more coronavirus than 100,000 people will be relocated along the banks of Yarlung Tsangpo River (upper stream of fears Brahmaputra), where the government is building a M A R C H 2 0 2 0 “modern town with complete facilities on an unavailable for human activities, a substantial extensive scale”, reported Xinhua on 18 number considering that the combined land March. size of Ngari, Nagchu, and Shigatse is more than 800,000 sq. km. More than 80 per cent The report quoted Tashi Dorjee, director of the of the targeted area under the plan consists Nature Reserve Management Division of the of protected areas from where all grazing is TAR Forestry and Grassland Bureau, as banned and nomadic livelihood is saying that the purpose of the relocation was criminalised. -

Population and Society in Contemporary Tibet

Population and Society in Contemporary Tibet Rong MA Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2011 ISBN 978-962-209-202-0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii List of Figures xiii Foreword by Melvyn Goldstein xv Acknowledgments xvii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Geographic Distribution and Changes in the Tibetan Population 17 of China 3. The Han Population in the Tibetan-inhabited Areas 41 4. Analyses of the Population Structure in the Tibetan Autonomous 71 Region 5. Migration in the Tibetan Autonomous Region 97 6. Economic Patterns and Transitions in the Tibet Autonomous 137 Region 7. Income and Consumption of Rural and Urban Residents in the 191 Tibetan Autonomous Region 8. Tibetan Spouse Selection and Marriage 241 vi Contents 9. Educational Development in the Tibet Autonomous Region 273 10. Residential Patterns and the Social Contacts between Han and 327 Tibetan Residents in Urban Lhasa Notes 357 References (Chinese and English) 369 Glossary of Terms 385 Index 387 List of Tables Table 2.1. The Geographic Distribution of Ethnic Tibetans in China 21 Table 2.2. -

Report on Tibetan Herder Relocation Programs

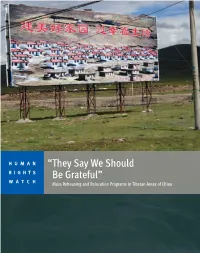

HUMAN “They Say We Should RIGHTS Be Grateful” WATCH Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Map: Tibetan Autonomous Areas within the People’s Republic of China ............................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................