Kwazulu-Natal Province South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessments of the Proposed Msinga New Town Centre Development at Cwaka, Msinga Local and Mzinyathi Regional District Municipalities, Kwazulu-Natal

Msinga Town Centre Development PHASE 2 CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENTS OF THE PROPOSED MSINGA NEW TOWN CENTRE DEVELOPMENT AT CWAKA, MSINGA LOCAL AND MZINYATHI REGIONAL DISTRICT MUNICIPALITIES, KWAZULU-NATAL ACTIVE HERITAGE CC For: Green Door Environmental Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] 11 November 2018 Fax: 086 7636380 www.activeheritage.webs.com Active Heritage CC 1-1 Msinga Town Centre Development TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT ..................................................... 6 1.1. Details of the area surveyed: ................................................................................... 6 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ........................................................ 6 2.1 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 6 2.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey ............................................................. 7 2.2.1 Visibility ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Disturbance ......................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Details of equipment used in the survey .................................................................. 7 3 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED ............................................... 8 3.1 Locational data ....................................................................................................... -

Umlalazi Strategic Planning Session

UMLALAZI STRATEGIC PLANNING SESSION INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLANNING Lizette Dirker IDP Coordination Business Unit INFORMANTS OF THE IDP SOUTH AFRICAN PLANNING SYSTEMS National Provincial Local District wide PGDS Vision 2030 DGDP (Vision 2035) (Vision 2035) National IDP PGDP Development 5 years Plan National Provincial Municipal Planning Planning Council Commission Commission WARD BASED SDGs SDGs PLANS “KZN as a prosperous Province with healthy, secure and skilled population, living in dignity and harmony, acting as a gateway to Africa and the World” Sustainable Development Goals AGENDA 2063 50 Year Vision • Agenda 2063 is a strategic framework for the socio-economic transformation of the continent over the next 50 years. It builds on, and seeks to accelerate the implementation of past and existing continental initiatives for growth and sustainable development Adopted in January 2015 • Adopted in January 2015, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia by the 24th African Union (AU) Assembly of Heads of State and Government 10 Year implementation cycle • Five ten year implementation plan – the first plan 2014-2023 1. A prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable 5. An Africa with a strong cultural development identity, common heritage, shared values and ethics 2. An integrated continent, politically united and based on the ideals of Pan-Africanism and the 6. An Africa whose development vision of Africa’s Renaissance is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children 3. An Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law 7. Africa as a strong, united and influential global player and partner 4. -

Existing Persberg Dam Wall Phase 1 Heritage Impact

EXISTING PERSBERG DAM WALL, PERSBERG FARM (PORTION LINDE NO 4733) SITUATED NEAR HELPMEKAAR, MSINGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, UMZINYATHI DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU- NATAL Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment 15 August 2019 FOR: Afzelia Environmental Consultants Deshni Naicker AUTHOR: JLB Consulting Jean Beater EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Applicant commenced with listed activities within a watercourse on Persberg Farm in August 2015 without the required authorisation. The dam wall has been raised to a height of 8.5 m and the dam covers an area of 8.4 hectares and is estimated to hold a capacity of 152 000 m³ (cubic meters) of water when full. As a result of a non-compliance with Section 25 of NEMA, a rectification process was commenced that included a Basic Assessment process in terms of the EIA Regulations, 2014 (as amended on 7 April 2017). This Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) report forms part of the Basic Assessment process. Interim comment received from the KwaZulu-Natal Amafa and Research Institute, the provincial heritage authority, stated that the development footprint falls within the red zone of the palaeontology sensitivity zone (very high fossil sensitivity) meaning that a palaeontologist must complete a survey of the development area. Furthermore, the area where the proposed development footprint is located used to have old structures situated close by and the area may therefore contain heritage artefacts or graves hence a heritage impact assessment (HIA) is required. This Phase 1 HIA report is in response to this requirement. The dam is situated within a watercourse on Persberg Farm (Portions Linde No 4733) that falls in the Msinga Local Municipality that falls within the Umzinyathi District Municipality, KwaZulu- Natal. -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

ETHEMBENI CULTURAL HERITAGE Amafa aKwazulu-Natali 22 January 2016 195 Jabu Ndlovu Street Pietermaritzburg 3200 August Telephone 033 3946 543 [email protected] Attention Bernadet Pawandiwa Dear Ms Pawandiwa Application for Exemption from a Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment Proposed Expansion of Dolerite Borrow Pit Pogela Farm, Heatonville Ntambanana LM, King Cetshwayo DM, KwaZulu-Natal. Project Area and Project description1 Mr John Readman of Pogela Farm, Heatonville, wishes to expand the existing dolerite borrow pit on his farm to an area of 3.11 ha, for commercial utilisation. This proposed expansion requires the conducting of a Basic Assessment in terms of both NEMA and DMR regulations. The existing borrow pit lies adjacent to an abandoned single-quarters residential compound constructed by Tongaat-Hulett in 1994. It is Mr Readman’ intention to demolish all structures in the course of expansion activities for the borrow pit. Observations No graves are located or reported in the immediate precinct of the planned expansion and any associated plant and services proposed2. The compound buildings are utilitarian, in a state of disuse and of no intrinsic significance. They are due to be demolished. The Ntabanana and Heatonville farms were granted in compensation to returning service-men after WWI (1918) and WWII (1945).3 These farms have been under sugar cane production for at least the last 40 to 50 years4. 1 J. Readman, pers.comm to LO van Schalkwyk. 2 Ibid. 3 2016. Heritage Scoping Report for the Invubu-Theta 400 kV Transmission -

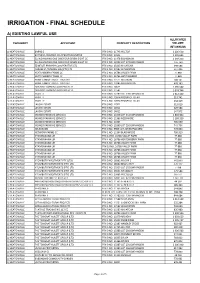

Irrigation - Final Schedule

IRRIGATION - FINAL SCHEDULE A) EXISTING LAWFUL USE ALLOCATED CATEGORY APPLICANT PROPERTY DESCRIPTION VOLUME (M 3/ANNUM) 1) HEATONVILLE BARNS D PTN 0 NO. 11745 HILLTOP 1 226 610 1) HEATONVILLE BAYANDA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE LIMITED PTN 0 NO. 11542 1 335 642 1) HEATONVILLE ELLINGHAM NO ONE ONE FOUR SEVEN EIGHT CC PTN 0 NO. 11478 ELLINGHAM 1 168 200 1) HEATONVILLE ELLINGHAM NO ONE ONE FOUR SEVEN EIGHT CC PTN 2 NO. 12922 LOT 272 EMPANGENI 155 760 1) HEATONVILLE EZIMTOTI PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE LTD PTN 0 NO. 13313 MAJATCHA 698 584 1) HEATONVILLE FORUM SA TRADING 306 (PTY) LTD PTN 4 NO. 11582 WALLENTON 547 496 1) HEATONVILLE HEATONBERRY FARMS CC PTN 2 NO. 16786 VALLEY FARM 77 880 1) HEATONVILLE HEATONBERRY FARMS CC PTN 3 NO. 16786 HEATONBERRY 77 880 1) HEATONVILLE HUME FAMILY TRUST - TRUSTEES PTN 0 NO. 11571 BOLARUM 700 141 1) HEATONVILLE HUME FAMILY TRUST - TRUSTEES PTN 0 NO. 12085 MERCHISTON 478 183 1) HEATONVILLE ISIBUSISO FARMING AND PROJECTS PTN 0 NO. 14625 1 596 540 1) HEATONVILLE ISIBUSISO FARMING AND PROJECTS PTN 3 NO. 11582 1 074 744 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 0 NO. 12280 LOT 239 EMPANGENI 1 012 440 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 3 NO. 10974 PROSPECT ESTATE 310 741 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 4 NO. 10974 PROSPECT ESTATE 234 419 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 12922 313 619 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 14014 529 584 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 14015 147 972 1) HEATONVILLE MONGO FARMING SERVICES PTN 0 NO. -

Msinga Municipal Idp 2017 2022

P a g e | KZ2 44 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY’S 4TH GENERATION INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017/2022 Developed in house PRIVATE BAG X530 TUGELLA FERRY 3010 033 4930762/3/4 Email: [email protected] [email protected] 1 Msinga Municipality’s 4th Generation IDP 2017 - 2022 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 2017-2022 IDP Table of Contents SECTION A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 “HOW WAS THIS INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN DEVELOPED?” 2 a) The UMzinyathi Framework Plan ............................................................................................................................. 2 TABLE 1. Compliance with Process Plan ......................................................................................................................... 3 b) Community -

Umzinyathi District Profile

2 PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 2. Brief overview ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1. Location .................................................................................................................. 7 3. Social Development ....................................................................................................... 9 3.1. Key Demographics .................................................................................................. 9 3.1.1. Population and Household Profile ........................................................................ 9 3.1.2. Age and Gender Profile ...................................................................................... 10 3.2. Health .................................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Covid-19 ................................................................................................................ 12 3.4. Poverty and Inequality ........................................................................................... 12 3.6. Education .............................................................................................................. 13 4. Economic Drivers ........................................................................................................ -

Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the Umhlathuze-Ulundi- Vryheid Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14

Report Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the uMhlathuze-Ulundi- Vryheid Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14 Milestone 5 Deliverable: Implementation and Phasing Plan KZN Cooperative Governance & Traditional Affairs: Client: LED Unit Reference: T&PMD1740-100-104R003F02 Revision: 02/Final Date: 24 July 2017 O p e n ROYAL HASKONINGDHV (PTY) LTD 30 Montrose Park Boulevard Montrose Park Village Victoria Country Club Estate Montrose Pietermaritzburg 3201 Transport & Planning Reg No. 1966/001916/07 +27 33 328 1000 T +27 33 328 1005 F [email protected] E royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 W +27 33 328 1005 T Document title: Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the [email protected] F Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14 royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 E Document short title: SC1 Implementation & Phasing Plan +27 33 328 1005 W Reference: T&PMD1740-100-104R003F02 [email protected] T Revision: 02/Final royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 F Date: 24 July 2017 +27 33 328 1005 E Project name: SC1 Corridor [email protected] W Project number: MD1740-100-104 royalhaskoningdhv.com T Author(s): Anton Martens (UPD), Bronwen Griffiths, Chris Cason, Lisa Higginson (Urban- F Econ), Nomcebo Hlophe, Rob Tarboton, Talia Feigenbaum (Urban-Econ) and E Andrew Schultz W Drafted by: Andrew Schultz Checked by: Date / initials: Approved by: Date / initials: Classification Open Disclaimer No part of these specifications/printed matter may be reproduced and/or published by print, photocopy, microfilm or by any other means, without the prior written permission of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd; nor may they be used, without such permission, for any purposes other than that for which they were produced. -

Curriculum Vitae Keagan Chase Kruger

CURRICULUM VITAE KEAGAN CHASE KRUGER Name of Firm: ACER (Africa) Environmental Consultants Name of Staff: Keagan Chase Kruger Profession: Environmental Consultant Date of birth: 27 April 1989 Years with firm: 4.5 years Nationality: South African RELEVANT PROJECT EXPERIENCE 2017: Dube Tradeport. The extension of the Tongaat Trunk Sewer Line, KwaZulu-Natal. [Environmental Compliance Officer]. 2017: Umzimvubu Local Municipality. Environmental Authorisation and associated permits/licenses for gravel access roads and concrete causeways near Mount Frere [Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Umzimvubu Local Municipality. Environmental Authorisation and associated permits/licenses for gravel access roads and concrete causeways near Mount Ayliff [Vegetation Assessment, Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Leo Mattioda. Environmental Authorisation and Associated Mining Permit for a Borrow Pit on Mr J Readman’s Farm near Heatonville [Vegetation Assessment, Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Kevin Lawrie Trust. Environmental Authorisation for the establishment of a layer poultry farm near Mtubatuba. [Vegetation Assessment and Wetland Delineation and Functional Assessment]. 2016/17: Eskom Distribution Limited. Clocolan-Ficksburg 88 kV Power Line and Marallaneng Substation, Free State. [Environmental Assessment Practitioner services for amending the existing Environmental Authorisation and obtaining Water -

Project Name

KING CETSHWAYO DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK DRAFT BASELINE REPORT PUBLIC REVIEW VERSION Prepared for: King Cetshwayo District Municipality Prepared by: EOH Coastal & Environmental Services June 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND TO THE KCDM EMF ................................................................. 7 1.1 Environmental Management Framework: Definition ...................................................................... 7 1.2 Legislative context for Environmental Management Frameworks .................................................. 8 1.3 Purpose of the KCDM EMF, Study Objectives and EMF applications .............................................. 8 1.4 Description of the need for the EMF ............................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 Development Pressures and Trends ............................................................................................. 9 1.5 Alignment with EMFs of surrounding District Municipalities and the uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................................................. 10 1.6 Approach to the KCDM EMF .......................................................................................................... 10 1.7 Assumptions and Limitations ......................................................................................................... 11 1.7.1 Assumptions .............................................................................................................................. -

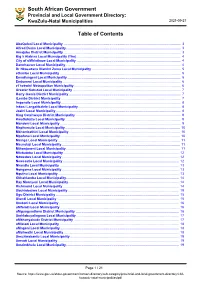

Export This Category As A

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Msinga Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2020

MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK DRAFT STATUS QUO REPORT JUNE 2020 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2020 Contents CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1 1.3 WHAT IS A SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2 1.4 LEGAL AND POLICY IMPERATIVES 3 1.5 RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER PLANS 4 1.6 DEFINING THE STUDY AREA 5 1.7 STRUCTURE OF THIS DOCUMENT 9 1.8 STUDY OBJECTIVES/ISSUES TO BE ADDRESSED 9 1.9 MUNICIPAL SPATIAL STRUCTURE AND DEVELOPMENT INFORMANTS 11 CHAPTER 2: STATUS QUO OF MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 12 2.1 LEGISLATIVE ENVIRONMENT 12 2.1.1 SOUTH AFRICAN CONSTITUTION AND PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (NO. 108 OF 1196) ..................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 MUNICIPAL SYSTEMS ACT (NO. 32 OF 2000) ........................................................................... 12 2.1.3 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ACT (NO. 107 OF 1998) ................................... 14 2.1.4 SOCIAL HOUSING ACT (NO.16 OF 2008) .................................................................................. 14 2.1.5 THE KWAZULU-NATAL HERITAGE ACT (NO 4 OF 2008) ........................................................... 16 2.1.6 SPLUMA (NO 16 OF 2013) ........................................................................................................ 17 2.2 POLICY ENVIRONMENT 21 2.2.1 PROVINCIAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY .........................................................