Title Opportunities and Constraints for Black Farming in a Former South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessments of the Proposed Msinga New Town Centre Development at Cwaka, Msinga Local and Mzinyathi Regional District Municipalities, Kwazulu-Natal

Msinga Town Centre Development PHASE 2 CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENTS OF THE PROPOSED MSINGA NEW TOWN CENTRE DEVELOPMENT AT CWAKA, MSINGA LOCAL AND MZINYATHI REGIONAL DISTRICT MUNICIPALITIES, KWAZULU-NATAL ACTIVE HERITAGE CC For: Green Door Environmental Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] 11 November 2018 Fax: 086 7636380 www.activeheritage.webs.com Active Heritage CC 1-1 Msinga Town Centre Development TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT ..................................................... 6 1.1. Details of the area surveyed: ................................................................................... 6 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ........................................................ 6 2.1 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 6 2.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey ............................................................. 7 2.2.1 Visibility ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Disturbance ......................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Details of equipment used in the survey .................................................................. 7 3 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED ............................................... 8 3.1 Locational data ....................................................................................................... -

Existing Persberg Dam Wall Phase 1 Heritage Impact

EXISTING PERSBERG DAM WALL, PERSBERG FARM (PORTION LINDE NO 4733) SITUATED NEAR HELPMEKAAR, MSINGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, UMZINYATHI DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU- NATAL Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment 15 August 2019 FOR: Afzelia Environmental Consultants Deshni Naicker AUTHOR: JLB Consulting Jean Beater EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Applicant commenced with listed activities within a watercourse on Persberg Farm in August 2015 without the required authorisation. The dam wall has been raised to a height of 8.5 m and the dam covers an area of 8.4 hectares and is estimated to hold a capacity of 152 000 m³ (cubic meters) of water when full. As a result of a non-compliance with Section 25 of NEMA, a rectification process was commenced that included a Basic Assessment process in terms of the EIA Regulations, 2014 (as amended on 7 April 2017). This Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) report forms part of the Basic Assessment process. Interim comment received from the KwaZulu-Natal Amafa and Research Institute, the provincial heritage authority, stated that the development footprint falls within the red zone of the palaeontology sensitivity zone (very high fossil sensitivity) meaning that a palaeontologist must complete a survey of the development area. Furthermore, the area where the proposed development footprint is located used to have old structures situated close by and the area may therefore contain heritage artefacts or graves hence a heritage impact assessment (HIA) is required. This Phase 1 HIA report is in response to this requirement. The dam is situated within a watercourse on Persberg Farm (Portions Linde No 4733) that falls in the Msinga Local Municipality that falls within the Umzinyathi District Municipality, KwaZulu- Natal. -

Msinga Municipal Idp 2017 2022

P a g e | KZ2 44 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY’S 4TH GENERATION INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017/2022 Developed in house PRIVATE BAG X530 TUGELLA FERRY 3010 033 4930762/3/4 Email: [email protected] [email protected] 1 Msinga Municipality’s 4th Generation IDP 2017 - 2022 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 2017-2022 IDP Table of Contents SECTION A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 “HOW WAS THIS INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN DEVELOPED?” 2 a) The UMzinyathi Framework Plan ............................................................................................................................. 2 TABLE 1. Compliance with Process Plan ......................................................................................................................... 3 b) Community -

Umzinyathi District Profile

2 PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE PROFILE: UMZINYATHI DISTRICT PROFILE 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 2. Brief overview ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1. Location .................................................................................................................. 7 3. Social Development ....................................................................................................... 9 3.1. Key Demographics .................................................................................................. 9 3.1.1. Population and Household Profile ........................................................................ 9 3.1.2. Age and Gender Profile ...................................................................................... 10 3.2. Health .................................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Covid-19 ................................................................................................................ 12 3.4. Poverty and Inequality ........................................................................................... 12 3.6. Education .............................................................................................................. 13 4. Economic Drivers ........................................................................................................ -

Export This Category As A

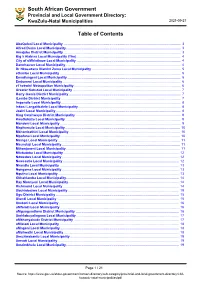

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Msinga Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2020

MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK DRAFT STATUS QUO REPORT JUNE 2020 MSINGA MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2020 Contents CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1 1.3 WHAT IS A SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2 1.4 LEGAL AND POLICY IMPERATIVES 3 1.5 RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER PLANS 4 1.6 DEFINING THE STUDY AREA 5 1.7 STRUCTURE OF THIS DOCUMENT 9 1.8 STUDY OBJECTIVES/ISSUES TO BE ADDRESSED 9 1.9 MUNICIPAL SPATIAL STRUCTURE AND DEVELOPMENT INFORMANTS 11 CHAPTER 2: STATUS QUO OF MSINGA MUNICIPALITY 12 2.1 LEGISLATIVE ENVIRONMENT 12 2.1.1 SOUTH AFRICAN CONSTITUTION AND PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (NO. 108 OF 1196) ..................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 MUNICIPAL SYSTEMS ACT (NO. 32 OF 2000) ........................................................................... 12 2.1.3 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ACT (NO. 107 OF 1998) ................................... 14 2.1.4 SOCIAL HOUSING ACT (NO.16 OF 2008) .................................................................................. 14 2.1.5 THE KWAZULU-NATAL HERITAGE ACT (NO 4 OF 2008) ........................................................... 16 2.1.6 SPLUMA (NO 16 OF 2013) ........................................................................................................ 17 2.2 POLICY ENVIRONMENT 21 2.2.1 PROVINCIAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY ......................................................... -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

eThembeni Cultural Heritage Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 Pietermaritzburg Telephone 033 326 1136 / 082 655 9077 / 082 529 3656 Facsimile 086 672 8557 [email protected] Company registration number CK 94/022770/23 VAT registration number 4690238268 eThembeni provides advice and guidance concerning heritage landscapes, places and activities, particularly in the context of development May 2012 eThembeni Specialises in the Following Activities: Heritage Impact Assessments (HIAs) as required by the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 as amended (NEMA), in compliance with Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 as amended (NHRA). Staff members are accredited to work throughout South Africa and will undertake work elsewhere in Africa. We identify heritage resources and recommend appropriate mitigation measures before development occurs. Although we do not undertake Palaeontological Impact Assessments we do refer clients to specialists in this field. Ancestral grave exhumation and reburial, including negotiation with families. Heritage resource management components of Strategic Development Plans and Environmental Management Frameworks. Excavation and management of archaeological sites. Preparation of nomination proposals to heritage authorities for the declaration of heritage resources as National and Provincial Heritage Landmarks, including the compilation of Integrated Site Management Plans. We conduct all our activities within appropriate legal frameworks, to ensure that places and landscapes are managed -

Spatial Development Framework for Msinga Local Municipality 2017

SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK FOR MSINGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY 2017/2018 REVIEW APRIL 2012 SUBMITTED BY: THE BLACK BALANCE – VUKA AFRICA CONSORTIUM REVIEWED IN-HOUSE BY: MSINGA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY 892 Umgeni Road, 1st Floor Stadium Building, DURBAN Suite 233, Private Bag X504, Northway 4065 TEL: (031) 303 3900 FAX: (031) 303 3911 P a g e | 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ADDRESSING THE MEC FOR COGTA’S COMMENTS ON THE FINAL SDF REVIEW This document represents the revised 2016/17 Msinga Spatial Development Framework 2016/17 (SDF) a summary of which is also included as an Annexure in the 2016/17 Msinga Integrated Development Plan (IDP). The adoption of this SDF is a legal requirement, and as such fulfils In the SDF assessment based on the May 2015/2016 (Final Report), the MEC for COGTA the requirements as set out within the Municipal Systems Act (MSA), No. 32 of 2000.This SDF commended the municipality for complying with Section 26(e) of the MSA and Section 12(1) also seeks to comply with the new Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (Act and Section 20 of the SPLUMA which required our Municipality to develop the Spatial No.16 of 2013). Development Framework (SDF) and ensure that it is included as an annexure to our IDP. The SDF is required to be in compliance with Section 2(4) of the Local Government Planning and Performance Management Regulations, 2001 (Reg. 796 of 2001) and the provisions of Section 21 of the SPLUMA. It was highlighted that Msinga’s SDF is, however, partially This SDF is an integral component of the Integrated Development Plan (IDP); it both informs compliant with the MSA Regulations and the SPLUMA provisions and the municipality is and translates the IDP spatially and guides how the implementation of the IDP should occur therefore requested to ensure that this is taken into cognizance when reviewing your current in space. -

Tourism Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu- natal TourisT Map not for sale STANDERTON Ekujabuleni Clinic Msuthu Vaal Gege Bothashoop Roberts Drift Heyshope Dam MOZAMBIQUE VILLIERS Amersfoort Ebenezer Mission Ponta Do Ouro Vaal PIET RETIEF NDUMO R546 Border Cave GAME Kosi Bay / Farazela (Oldest recorded Kosi Bay remains of RESERVE TEMBE De Kuilen R543 King’s Residence Homo Sapiens) Phongolo ELEPHANT Windveld R23 MPUMALANGA SWAZILAND PARK KOSI BAY NATURE RESERVE Cecil Marks Pass Klip Casino Delangesdrif Wag-’n-bietjie (closed to public) Tembe Nhlange PERDEKOP N J.C.I Clinic Elephant Kwangwanase 11 Mahamba NHLANGANO Lodge Sand Market Cornelia Assegaai Dirkies N R22 COASTAL FOREST Moolman 2 Nsongweni R34 MAPUTALAND MARINE SANCTUARY R103 R543 Phelandaba British R33 Dog Point Memorial Ntombe Berbice Sandspruit SIZELA FOREST Black Rock N Lady of 3 RESERVE Steel’s Drift Allemans Nek Jantjieshoek Pass Sorrow Clinic Rocktail Bay R543 VOLKSRUST Commondale WAKKERSTROOM PONGOLA BUSH Dingane’s ELEPHANT NATURE RESERVE Ntombe Salitje H Grave COASTAL FOREST Wilge Tholulywazi Golela-Lavumisa COAST R34 CHARLESTOWN Onverwacht Hlathikhulu Forest VREDE Luneburg N Lake 2 PHONGOLO Sibaya Laingsnek Laing’s Nek 1881 PONGOLA Mabibi Beach Klip NATURE Roadside Majuba 1881 Groenvlei Paulpietersburg Phongolo PHONGOLO GAME RESERVE Hully Point Luiperfskloof PARK Jozini Phongolo BIVANE DAM Dam MAPUTALAND MARINE RESERVE O’Neil’s Cottage NATURE PAKAMISA Leeukop SEEKOEIVLEI RESERVE Thalu Jozini NATURE The Natal Spa Mhlangeni GAME R66 H Doornkraal ITHALA Tiger Fishing R103 RESERVE Schulashoogte 1881 RESERVE Gobey’s Point INGOGO Adventure GAME RESERVE R34 Mbizo Botha’s Pass Cemetary Bivane Centre Magudu Bothaspass Madaka LOUWSBURG Bothaspas Knight’s Pass R33 R69 Mbazwana N White AMAZULU Lebombo Cliffs Ubombo SODWANA BAY NATIONAL PARK 11 Powkrowsky Mfolozi Memel Bloed Hlobane GAME RESERVE Mantuma Memorial UTRECHT Kambula Mkuze FREE Fort Amiel Buffels Holkrans 1879 R69 Nhlonhlela Ophansi Gate 1879 MKHUZE Ghost Coronation Amakhosi MKUZE FALLS Mountain Lancaster Hill Mkuze MKUZE ST. -

Umzinyathi District Municipality

uMzinyathi District Schools & Health Facilities !20 !21 !22 !23 !24 !25 !26 Mdlenevu P ! ! Kwambunda ! ! Nkande P Ndlanga- Sithan- mandla S dene P XY d (EC) P214 e o l ! XYP258 B Ntshangase P P P ! XYP54 Nhlokomo P ! ! ! Zisize P ! Nkande × Tlokweng P Clinic ! Nkanda XYP60 Leneha Tumisi S ! Buffels Battersea Ikaheng P Park P XYP546 ! !19 UõD301 ! Esixhobeni P Haladu R Haladu P ! ! Öa33 Celumusa S XYP296 Endumeni Local Municipality !Q !Q d ! e Tayside P lo Mphazima P B ! UõD462 XYP60 Ukuphumula S Ebrahim Lockat S ! Thembekile P Lindokuhle P ! ! Ndatshana P! Nothisiwe Pp !17 !18 ! ! !27 !28 !29 !30 k Ndatshana ter D437 S Uõ ! Siyam- Dr Alden Bloodriver Sp Esikhumbuzweni S D763 ! ! ! thanda P Lloyd Nature Uõ ! Qwezi P Vegkop P ! Bayabonga P Van Bu Nqutu Conservation ff Lutheran P "" el ! Rooyen s ! XYP272 Mathukulula S UõD471 XYP364 Mgidla H Bapaume P ! R ! Jojosi ! R ! R D1303 Mhlungwane P ! a68 Mkhonjane Uõ Dundee Empathe ! Ö Enyanyeni P (EC) Clinic R Police Stn Clinic Dundee 68 Dundee Pp ×! D1348 ! Öa Buhlebuzovama P ! õ XYP54 ! XYP297 Munywana P U R Magabeng S Hlomisa P Dundee Js Mphondi P! Pynes 33 ! Ndindindi ! ! Öa Qediphika P ! Dundee J ! ! Dundee S Æü õD436 XYP554 Farm Sarel × Dundee P U Mkhonjane Nomashaka P ! Kwadophi P Cilliers S ! ! ! Umzinyathi ! Zwelisha P ! Dundee H Ethangeni C Nhlalakahle S ! Velaphansi S D1347 ! unyana "" ML Sultan S ! Glencoe P Pro Nobis Lsen PÆ! District Mkhonjane P ! ! Uõ Mandlenyosi P XYP36 Mv Mooiplaas ! G!lencoe Umzinyathi EC ! ! × ! Glencoe Pp × Office ! ! Egoqwaneni P Æü Ichthus Christian P Intoyethu -

Pro-Poor Value Chain Governance in the Mtateni Irrigation Scheme At

Pro-poor value chain governance in the Mtateni irrigation scheme at Tugela Ferry, Msinga, KwaZulu-Natal Thokozile Cynthia Buthelezi A minithesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Philosophiae: Land and Agrarian Studies in the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies. Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Date submitted for examination: December 2013 Supervisor: Professor Benjamin Cousins 0 Pro-poor value chain governance in the Mtateni irrigation scheme at Tugela Ferry, Msinga, KwaZulu-Natal Thokozile Cynthia Buthelezi KEYWORDS Smallholder farmers Agrarian reform Irrigation schemes Fresh produce Inputs supply Marketing Agro-food industry Value chains Value chain governance i ABSTRACT Pro-poor value chain governance in the Mtateni irrigation scheme at Tugela Ferry, Msinga, KwaZulu-Natal T.C. Buthelezi MPhil in Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Insitute of Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies This study explored value-chain governance in the Tugela Ferry Irrigation Scheme in KwaZulu-Natal, and presents data on input markets, vegetable production and output markets. Rural poverty is a major problem in post-apartheid South Africa, and smallholder agriculture has been identified by the Economic Development Department as a key component of its New Growth Path framework. Some scholars argue that since water is a scarce resource, irrigation farming should form a key focus of pro-poor land redistribution policy. The 1994 democratic dispensation saw the dismantling of the agricultural homeland parastatals which managed these schemes, causing them to collapse or near collapse. Yet they may have the potential to reduce rural poverty. While markets are key for viable production of fresh produce, some scholars assert that globally, input suppliers, food processors and supermarkets dominate the agro-food industry resulting in negative outcomes for smallholder producers. -

Final Msinga Municipal Housing Plan Report

MSINGA MUNICIPAL HOUSING PLAN 1. INTRODUCTION: 1.1 Isibuko se-Africa (in association with SRK Consulting) was appointed, in January 2007, to assist the Msinga Municipality with the preparation of a Municipal Housing Plan. 1.2 “Housing” refers to an integrated approach to development with the primary focus being on the delivery of shelter. As indicated in Figure 1 below, housing includes, among others, the development of housing units, service delivery, the upgrading of land tenure rights, social and community development and planning policy issues. Future housing projects should aim to achieve all of these development goals. Figure 1: Housing Concept SUSTAINABLE HUMAN SETTLEMENT Shelter Community Facilities Community Poverty Alleviation Poverty NATION BUILDING Service Delivery Service DEVELOPMENT INTEGRATED Land Land Tenure Job Creation Job Self Self Esteem Policy Legislation Programmes Budget SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Housing delivery within the Msinga Municipal Area occurs mainly in the form of state funded, low cost housing in which the municipality serves as a developer. 1.3 The purpose of the National Housing Code (March 2000 is to set out clearly the National Housing Policy of South Africa. It identifies the primary role of the municipality as taking all reasonable and necessary steps, within the framework of national and provincial legislation and policy, to ensure that the inhabitants within its area of jurisdiction have access to adequate housing on a progressive basis. This entails the following: Initiating, planning, facilitating and co-ordinating appropriate housing development. This can be undertaken by the municipality itself or by the appointment of implementing agents. 1 ISIBUKO SE-AFRICA JANUARY 2008 MSINGA MUNICIPAL HOUSING PLAN Preparing a housing delivery strategy and setting up housing development goals.