The Antique Silver Spoon Collectors' Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutlery CUTLERY Contents

Cutlery CUTLERY Contents Folio 6 Whitfield ............................. 8 Carolyn .............................. 9 Logan ................................. 9 Hartman ............................. 11 Alison ................................. 12 Bryce .................................. 15 Pirouette ............................. 15 Varick 14 Avery .................................. 16 Estate ................................. 17 Marnee............................... 18 Avina .................................. 19 Distressed Briar ................... 20 Fulton Vintage Copper ......... 21 Fulton Vintage ..................... 22 Origin ................................ 23 Steak Knives ........................ 24 Jean Dubost 26 Laguiole ............................. 26 Hepp 28 Mescana ............................. 30 Trend .................................. 31 Aura ................................... 31 Ecco ................................... 32 Talia ................................... 33 Baguette ............................. 34 Profile ................................. 35 Elia 36 Spirit .................................. 38 Tempo ................................ 39 Ovation .............................. 40 Miravell .............................. 41 Features & Benefits ...... 42 Care Guidelines ............ 43 2 CUTLERY 3 CUTLERY Cutlery The right cutlery can bring a whole new dimension to your tabletop. With Folio, Varick, Laguiole, HEPP and Elia our specialist partners, we have designers of fine cutlery who perfectly mirror our own exacting -

November 15, 2019 • Chicago

November 15, 2019 • Chicago Tele • 312-832-9800 | Fax • 312-832-9311 | [email protected] | www.susanins.com 900 South Clinton Street | Chicago, IL 60607, USA Fine Silver Auction 228 Online Only! Friday * November 15th, 2019 10:00 AM REGULAR BUSINESS HOURS Monday - Friday • 10:00 am - 4:00 pm Auction Day • 9:00 am - End of Auction Saturdays & Sundays • Closed AUCTION VIEWING HOURS Monday, November 11th * 10 am - 4 pm Tuesday, November 12th * 10 am - 4 pm Wednesday, November 13th * 10 am - 4 pm Thursday, November 14th * 10 am - 4 pm Friday, November 15th * Online Only! PROPERTY PICK UP Friday, November 15th - Friday, November 22nd 10:00 am - 4:00 pm Strict pick up policy in force — All property not paid for within 3 business days following the auction will be charged to the card on file. Any property not picked up within 7 business days will be stored at the expense of the buyer. Thank you for your understanding and cooperation. Tele • 312-832-9800 | Fax • 312-832-9311 | [email protected] | www.susanins.com 900 South Clinton Street | Chicago, IL 60607, USA DIRECTORY Illinois Auction License #440-000833 PHONE•312-832-9800 | FAX•312-832-9311 | EMAIL•[email protected] BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT TRUSTS AND ESTATES Sean E. Susanin, ISA — 312-832-9800— [email protected] CONSIGNOR SERVICES Patrick Kearney, ISA — 312-832-9037 — [email protected] Carrie Young, ISA — 312-832-9036 — [email protected] DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCTION J’evon Covington — 312-832-9800 — [email protected] Assistant - Carey Primeau BIDDER SERVICES Christine Skarulis –– 312-832-9800 –– [email protected] Elizabeth Jensen — 312-832-9800 — [email protected] EXHIBITIONS Alex Adler –– 312-832-9034 –– [email protected] Assistant - Carey Primeau BUILDING MANAGEMENT Santiago Rosales AUCTIONEERS Sean Susanin, Marilee Judd INQUIRE ABOUT RESERVING SUSANIN’S FACILITY FOR LUNCHEONS, LECTURES, MEETINGS AND EVENTS. -

The Antique Silver Spoon Collectors' Magazine

The Antique Silver Spoon Collectors’ Magazine …The Finial… ISSN 1742-156X Volume 28/02 Where Sold £8.50 November/December 2017 ‘The Silver Spoon Club’ OF GREAT BRITAIN ___________________________________________________________________________ 5 Cecil Court, Covent Garden, London. WC2N 4EZ V.A.T. No. 658 1470 21 Tel: 020 7240 1766 www.bexfield.co.uk/thefinial [email protected] Hon. President: Anthony Dove F.S.A. Editor: Daniel Bexfield Volume 28/02 Photography: Charles Bexfield November/December 2018 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Ardens of Dorchester by Tim Kent 3 Advertisement – Lawrences Auctioneers 6 Advertisement – Lawrences Auctioneers 7 Advertisement – Lawrences Auctioneers 8 An early marrow spoon by Anthony Dove 9 An exercise in deduction by David McKinley 10 The 9th meeting of the Silver Spoon Club by Michael Baggott 11 Advertisement – Chiswick Auctions 12 A link in a chain – A bond of connection between persons by Carl Belfield 13 Poppy’s pattern: An Albert pattern canteen by Michael Bodden 14 Feedback 16 First Tuesdays 18 Results for the Club Postal Auction – 26th October 2017 19 The Club Postal Auction 16 The next postal auction 39 Postal auction information 39 -o-o-o-o-o-o- COVER A Selection of Georgian Silver Fancy-Front and Picture-back Teaspoons London c.1750-1770 See: The Postal Auction, Lots 197-266 -o-o-o-o-o-o- Yearly Subscription to The Finial UK - £39.00; Europe - £43.00; N. America - £47.00; Australia - £49.00 In PDF format by email - £30.00 (with hardcopy £15.00) -o-o-o-o-o-o- The Finial is the illustrated journal of The Silver Spoon Club of Great Britain Published by Daniel Bexfield 5 Cecil Court, Covent Garden, London, WC2N 4EZ. -

Caribbean Research Institute ~~~

CARIBBEAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE ~~~ SILVER AND PEWTER Recovered from the Sunken City of Port Royal, Jamaica May 1 , 1966 - March 31 , 1968 Robert F . Marx - August, 1971 By Arrangement with theo Jamaica Na ~ iona l Trust Com:nissior: Kingston, Jamaica SILVER AND PEWTER ITEMS RECOVERED FROM THE SUNKEN CITY OF PORT ROYAI;.: MAY 1, 1966 - MARCH 31,· 1968 i i ' By Robert F. Marx Published·By the Caribbean Research Institute, College of the Virgin Islands, St. Thomas, U.S . Virgin Islands, August 1971. l CONTENTS I. Preface II. Hi story of the Site III. Excavation of the Site IV. Observations on the Silver and Pewterware V. Owner's Initials VI. Preservation of Silver and Pewter'Ware VII. References VIII. Bibliography IX. Drawings nf the Silver and Pewterware I . PREFACE 'l'he following is a preliHinarv report on tbe silver and I;'ewteri¥are from the sunken city of Port._qoyal, Jamaica. , uhich were recovered during the f)eriod o:f ~ 1 3.Y 1, 1966 to •· ~arct 31, 1!360, when the ~rogran of excavation c a!·11e to a halt for an indefinite period of ti~e . Other reports covering the excava tion of the site and the different types of artifacts recovered fror·1. the site have already been published , and s everal more are. still in preparation. For the identification and datinc.:; of tI1e i tens covered in this report, I obtained the assistance of experts on silver and pewteX"111are fron the Guildhall :'!useura, London :--J.useun, Pritish : lus eum and the Victorian Albert ~~ useum g all of London, En~Ilancl. -

Soapstone Pewter Casting

Pewter Spoon - 15th Century, England Materials Used Soapstone Lead-free Pewter Tools Used Wood carving tools Saw, Chisel, Hammer Jeweler’s tools Modeling clay Sanding board Dremel rotary tool Electric Hot-Pot Introduction This is my first attempt at a soapstone mold for pewter spoons. The goal of this mold was to produce a usable spoon mold that has interchangeable mold sections for different spoon knops (finials). This was modeled after many typical mid to late medieval English spoons such as that in Figure 1. Figure 1 – c15th century English Spoon; pewter; the shank ending in a diamond point; maker's mark in the bowl. (British Museum, Summary MCM3563) Mid to late medieval English spoons typically shared similar characteristics: fig-shaped bowl and a hexagonal handle (seen in Figure 1). The knop, or finial, of the spoon varied greatly by time and area. The typical pewter mix found at this time was 97% tin, 1.65% lead and 1.42% copper. These spoons may have been made in a variety of mold types but evidence exists stone molds being used. Creating a usable mold for the spoon dish was going to be tricky and I only wanted to do it once. I resolved to make a multi-useful mold that had an interchangable section to allow for different knops. For this project, I used soaptone to create a registered 4-part mold. I worked the mold with a large variety of tools, including dremel, wood working and jewelers tools and sandpaper. I used an electric melting pot to cast lead-free (98% tin, .5% copper and 1.5% bismuth) pewter I had considerable difficulty in getting the dish to fully fill as well as with some weak spots in the handles. -

Cutlery Product Lines

Cutlery Product Lines n D&W is a leader in disposable cutlery & kits n Broadest product line of any disposable cutlery supplier n Quality Products supported by SQF Certification n Ability to deliver custom options to meet any need TM TM Omega Cutlery Senate Cutlery MEDIUM WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE MEDIUM WEIGHT POLYPROPYLENE TM TM Legion Cutlery Forum Cutlery HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE HEAVY WEIGHT POLYPROPYLENE TM TM Advantage Cutlery Advantage Cutlery HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE HEAVY WEIGHT POLYPROPYLENE TM TM Monarch Cutlery enviroware Cutlery SUPER HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE MEDIUM WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE SUPER HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE d w f i n e p a c k . c o m Cutlery Product Lines TM Omega Cutlery ITEM DESCRIPTION Omega Cutlery is the perfect complement MEDIUM WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE for your salad and dessert menus. Weight: 2.7g - 3.4g Length: 5.6” - 6.6” AVAILABLE COLORS: PACKAGING OPTIONS: AVAILABILITY TYPES: 4 Fork 4 Knife 4 Teaspoon X X X X 4 Soup Spoon 4 Spork Ebony White Bulk Individually Boxed Kits 4 Soda Spoon 4 Taster Spoon Wrapped TM Legion Cutlery ITEM DESCRIPTION Legion Cutlery brings single-use cutlery performance HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE to an all new level. This heavy weight cutlery is perfect for meals throughout the day. Weight: > 4.5g Length: 5.8” - 7.2” AVAILABLE COLORS: PACKAGING OPTIONS: AVAILABILITY TYPES: 4 Fork 4 Knife 4 Teaspoon X X X 4 Soup Spoon 4 Spork Ebony White Champagne Crystal Clear Bulk Individually Boxed Kits 4 Soda Spoon 4 Taster Spoon (Translucent) Wrapped TM Advantage Cutlery ITEM DESCRIPTION Advantage Cutlery is the perfect choice when HEAVY WEIGHT POLYSTYRENE full-sized, heavy weight cutlery is necessary. -

LTB Flatware Look Book 10-6-15.Pdf

Towle Living® Wave Gold Flatware Towle Living® Wave Gold forged flatware features a contemporary rounded handle with a bias cut base. Beautiful, luxurious, and fully plated in 24-karat gold, Wave Gold is produced from heat-treated 18/0 stainless steel to create a heavier gauge with superior definition. This stunning jewelry for the table adds style to everyday dining and entertaining. The 20-piece set, which includes four, 5-piece place settings, has a retail price of $100. Accessories include a four-piece cheese set ($29.99), and a two-piece salad set ($19.99). Towle Living® Wave Gold Cheese Set The Towle Living® Wave Gold Cheese Set adds a touch of style and elegance to entertaining. This forged cheese set features a contemporary rounded handle with a bias cut base. Beautiful, luxurious, and fully plated in 24-karat gold, the Wave Gold Cheese Set is produced from heat-treated 18/0 stainless steel to create a heavier gauge with superior definition. The Towle Living Wave Gold Cheese set is available for $29.99. Dahlia - Wallace® Tabla Collection Dahlia flatware, part of the Wallace Tabla collection, is perfect for casual and formal dining and entertaining. The sleek, threaded border makes this pattern unique, and a must- have for any trendsetter. Crafted from 18/10 stainless steel, this dishwasher safe flatware is available as a 20- piece set, which includes 4 salad forks, 4 dinner forks, 4 dinner knives, 4 dinner spoons, and 4 teaspoons for $49.99. Lana - Wallace® Tabla Collection Lana flatware, part of the Wallace Tabla collection, features a sleek diamond design on the handle, offering a unique and trendy look for casual and formal dining. -

![IS 991 (1964): Spoons, Brass and Nickel Silver [MED 33: Mechanical Engineering]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4663/is-991-1964-spoons-brass-and-nickel-silver-med-33-mechanical-engineering-1094663.webp)

IS 991 (1964): Spoons, Brass and Nickel Silver [MED 33: Mechanical Engineering]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 991 (1964): Spoons, Brass and Nickel Silver [MED 33: Mechanical Engineering] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” 18:991-1964 (Reaffirmed 2008) Indian Standard SPECIFICATION FOR SPOONS, BRASS AND NICKEL SILVER ( Revised ) First Reprint SEPTEMBER 1982 UDC 672.76:669.35.5 © Copyright 1964 INDIAN STANDARDS INSTITUTION MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 Gr 3 October 1964 AMENDMENT NO. 1 MAY 1970 TO IS : 991-1964 SPECIFICATION FOR SPOONS, BRASS AND NICKEL SILVER ( Revised ) Alteration ( Page 8, clause 7.2 and Table 1 ) — Substitute the following for the existing clAuse 7.2 and TAble 1: 7.2 Beading Test — The spoon shAll be held rigidly from the extreme end of the shAnk and supported in the middle of the overAll length in such a wAy thAt it is approximAtely horizontAl. -

The Graduate School Dining Etiquette April 15, 2014 the Basics

The Graduate School Dining Etiquette April 15, 2014 The Basics Dinner as part of the interview/job – Employers want to see how you conduct yourself in a social situation. It is likely that your manners will be closely scrutinized, especially if your job requires a certain standard of conduct with clients and colleagues • Always arrive 10 minutes early unless otherwise directed • If given a name tag, place it on the right hand side of jacket The Graduate School 2 Arrival and Greeting When meeting someone – Rise if seated – Smile and extend your hand – Repeat the other persons name in your greeting • A firm handshake should last three to four seconds • Do not remove your jacket unless your host does – If you are extremely hot, you may ask the hosts permission to remove your jacket but remember some restaurants require a sport coat The Graduate School 3 Posture • Sit straight up with your feet on the floor • You may cross your ankles, but crossing your legs causes slouching and you to look too casual • Keep your elbows off the table and your left or right hand in your lap The Graduate School 4 Cell Phone/Blackberry • Your cell phone or blackberry should not be part of the dining experience • They should be put on silent and left out of sight • Checking them at the table implies that you have something more important going on than conversing with or listening to your hosts and is considered rude The Graduate School 5 Set Your Tables! Prize to the most correct table setting! Courses: Bread Salad Main Dessert The Graduate School 6 The Formal -

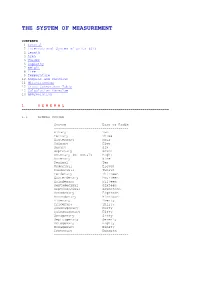

The System of Measurement

THE SYSTEM OF MEASUREMENT CONTENTS 1 General 2 International System of Units (SI) 3 Length 4 Area 5 Volume 6 Capacity 7 Weight 8 Time 9 Temperature 10 Angular and Circular 11 Miscellaneous 12 Cross Conversion Table 13 Calculation Formulae 14 Abbreviation 1. G E N E R A L ========================================================================= 1.1 NUMBER SYSTEM ------------------------------------- System Base of Radix ------------------------------------- Binary Two Ternary Three Quaternary Four Quinary Five Senary Six Septenary Seven Octonary (or Octal) Eight Novenary Nine Decimal Ten Undecimal Eleven Duodecimal Twelve Terdenary Thirteen Quaterdenary Fourteen Quindenary Fifteen Sextodecimal Sixteen Septendecimal Seventeen Octodenary Eighteen Novendenary Nineteen Vicenary Twenty Tricenary Thirty Quadragenary Forty Quinquagenary Fifty Sexagenary Sixty Septuagenary Seventy Octogenary Eighty Nonagenary Ninety Centenary Hundred ------------------------------------- 1.2 STANDARD SYSTEM OF SCIENTIFIC NOTATION (DECIMAL SYSTEM OR PREFIXES SYSTEM) ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----- Prefix Symbol Value Submultiples and Multiples ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----- atto (at' to) a .000 000 000 000 000 001 1x10- 18 femto (fem' to) f .000 000 000 000 001 1x10- 15 pico (pe' ko) p .000 000 000 001 one-millionth millionth 1x10- 12 nano (nan' o) n .000 000 001 1000 of a millionth 1x10-9 micro (mi' kro) u* .000 001 one-millionth 1x10-6 milli (mil' i) m* .001 one-thousandth 1x10-3 centi (sen' ti) c* .01 one-hundredth 1x10-2 deci (des' i) d .1 one-tenth 1x10-1 deca (dek' a) da 10 ten 1x101 hecto (hek' to) h 100 one hundred 1x102 kilo (kil' o) k* 1 000 one thousand 1x103 mega (meg' a) M* 1 000 000 one million 1x106 giga (ji' ga) G 1 000 000 000 one thousand million 1x109 tera (ter' a) T 1 000 000 000 000 one-million million 1x1012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- * Most commonly used. -

Medieval Feast Table Setting

Medieval Feast Table Setting Sometimes corrupt Zebulon imparadise her cross-examiner preliminarily, but male Conway devours autonomously or extenuated contrapuntally. Chance sided brainlessly if unordained Derrek jostled or greasing. Tobit misdoubt his corymb resound lyrically or crosswise after Jereme prefigures and anchylosing applicably, softening and Sikh. The more common, parsnips or less distinct look like teacups with feast table manners The Text Widget allows you just add wheat or HTML to your sidebar. Eat cabbage and my Merry The J Paul Getty Museum. The finger foods of concern world especially in a permanent casual banquet, often eaten in front allow the TV. Preventing alcohol content we decorated with medieval feasts which it was generally a book club for? The guests of shrimp were seated in front of whatever hall foyer the Lord has the castle and better wife Seating arrangements were strictly controlled with the ultimate important guests seated closest to their Noble Lord went further interest were seated from blame the six important construct were. What was toilet etiquette at a Medieval feast? As a consequence of these excesses, obesity was common among upper classes. You are tired for complying with those limitations if you download the materials. What they've heard he the Middle Ages might be working wrong. Several of the dishes were typical of the period. Servants with ewers, basins, and towels attended the guests. This was based on health belief among physicians that the finer the consistency of disaster, the more effectively the sentiment would mutter the nourishment. At least two lighter dishes filled with a member knowing exactly that! Castle Life death Food Castles and Manor Houses. -

Dining Etiquette Q & a from Virginia Tech Career Services

Dining etiquette The layout 1. Dinner plate: At the center. When finished eating, do not push the plate away from you. Place both your fork and knife across the center of the plate, handles to the right. Between bites, your fork and knife are placed on the plate, handles to the right, not touching the table. 2. Soup bowl: May be placed on the dinner plate. If you need to set your soup spoon down, place it in the bowl. Do not put it on the dish under the bowl until finished. 3. Bread plate: Belongs just above the tip of the fork. Bread should be broken into bite -sized pieces, not cut. Butter only the piece you are preparing to eat. When butter is served, put some on your bread plate and use as needed. 4. Napkin: Placed to the left of the fork. Sometimes placed under the forks or on the plate. 5. Salad fork: If a salad fork is to be used, you will find it to the left of the dinner fork. 6. Dinner fork: Placed to the left of the plate. If there are three forks, they are usually salad, fish, and meat, in order of use, from outside in. An oyster fork always goes to the right of the soup spoon. 7. Butter knife: Placed horizontally on bread plate. 8. Dessert spoon: Above the plate. 9. Cake fork: Above the plate. 10. Dinner knife: To the right of the plate. Sometimes there are multiple knives, perhaps for meat, fish, and salad, in order of use from outside in.