RJTF Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS Long Form

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS IN THE MOVEMENT TO END SEXUAL & DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Ida B. Wells The Combahee River Collective Wells, a suffragist and temperance activist, famously and fearlessly This Boston-based collective spoke against lynchings, and also of black feminist lesbians worked to end sexual violence wrote the seminal essay The against black women. Radically, Combahee River Collective Wells identified scapegoating of Statement, centering black black men as rapists as a projection feminist issues and identifying of white men's own history of sexual white feminism as an entity violence, often enacted against black that often excludes or women. sidelines black women. They campaigned against sexual assault in their communities and raised awareness of the racialized sexual Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw violence that black women face. A legal scholar, writer, and activist, Crenshaw famously coined the term Loretta Ross "intersectionality," forever impacting An academic, activist, and writer, the way we think about social identity. Ros s has written extensively on Crenshaw's work draws attention to the topic of reproductive justice the fact that black women exist at the and is a pioneer of reproductive intersection of multiple oppressions justice theory. Her work has and experience the dual violence of brought attention to the ways both racism and misogyny. reproductive coercion, racism, and sexual violence intersect. Harriet Jacobs Tarana Burke Jacobs was born into An activist and public speaker, Burke slavery and sex ually founded the wildly successful assaulted by her owner, #MeToo movement. Specifically and eventually escaped created to highlight violence by hiding undetected in experienced by marginalized an attic for seven years. -

PDF SVA Handbook 2020–21

2020/2021 SVA Handbook SVA • 2020 / 2021 20 /21 SVA Handbook CONTENTS President’s Letter 2 The College 3 Academic Information 9 Student Information 23 Faculty Information 44 General Information 55 Standards, Procedures, Policies and Regulations 69 SVA Essentials 93 2020–2021 Academic Calendar 113 Index 119 SVA.EDU 1 THE SVA HANDBOOK provides faculty, students and administrative staff with information about the College, its administration, services and processes. In addition, the Handbook contains policies mandated by federal and state regulations, which all faculty, students and administrative staff need be aware of. In this regard, I would especially like to call your attention to the sections on attendance (pages 12 and 46), the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (page 85), Student Disruptive and Concerning Behavior (page 74), Title IX procedures (page 84) and the SVA policy on alcohol and drugs (page 70). We look forward to the 2020–2021 academic year. Our students, this year from 45 states, one U.S. territory and 49 countries, will once again pursue their studies with the focused guidance of our renowned professional faculty. DAVID RHODES President August 2020 2 SVA HANDBOOK THE COLLEGE Board of Directors 4 Accreditation 4 SVA Mission Statement 4 SVA Core Values 4 History of SVA 5 Academic Freedom 6 First Amendment Rights 6 SVA Student Profile 7 SVA.EDU 3 BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Interior Design program leading to the Brian Palmer Bachelor of Fine Arts in Interior Design is ac- Joseph F. Patterson credited by the Council for Interior Design Anthony P. Rhodes Accreditation (accredit-id.org), 206 Grand- David Rhodes ville Avenue, Suite 350, Grand Rapids, MI Lawrence Rodman 49503-4014. -

The Lynching of George Floyd: Truth Vs. Copaganda

The Lynching of George Floyd: Truth vs. Copaganda https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7111 USA The Lynching of George Floyd: Truth vs. Copaganda - IV Online magazine - 2021 - IV555 - April 2021 - Publication date: Wednesday 21 April 2021 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/5 The Lynching of George Floyd: Truth vs. Copaganda This article was written before the conclusions and the verdict. "I CALLED THE police on the police," one eyewitness told the jury. The prosecution opened the trial of Derek Chauvin with a 9-minute and 29-second ("929") video of the cop's knee murdering George Floyd on May 25, 2020 in Minneapolis. The Medical Examiner and other medical doctors said he was not moving minutes after the knee was placed on his neck. The evidence by eyewitnesses and testimony by police officers, including the chief, declared that Chauvin was not following police policy and should be convicted. The Blue Wall of silence was cracked. The top police officials' argument is that Chauvin is an exception to "good policing." African Americans and many others, on the other hand, see Chauvin as the norm of modern policing especially as it applies to Black and Brown people. $27 Million Civil Settlement A few days before the trial began the Minneapolis City Council agreed, March 12, to a historic civil settlement paying the Floyd family $27 million the largest pre-trial settlement ever. Chauvin's lawyers unsuccessfully tried to use the settlement as a reason to move the criminal trial out of Minneapolis. -

Python Projects for Resume Reddit

Python Projects For Resume Reddit Chet rape his klutz settles wrong or extraneously after Neron prune and covings proprietorially, undisturbing and Caldwellallegiant. neverSniffiest dibble Torrin any levigating parroquets! some Caen after ringent Marmaduke insists snappishly. Anabatic or suchlike, This location that on how to make the reddit python project on a java or command Then I decided to personalize my cover paid and resume summary then route to send. CodeSignal Coding Tests and Assessments for Technical. Can perform give baby some good examples of mediumhigh level projects that. Self-taught Python and CC What of some projects I can. Advanced Programming Projects Reddit. Get instant coding help build projects faster and read programming tutorials from. I managed to surface a script that asks for order number checks of the remainder is. Search for code editors and you to properly. ShadowmooseRedditDownloader Scrapes Reddit to GitHub. Best Machine Learning GitHub Repostories & Reddit. Python vs powershell reddit ERAZ 2020. Entry level programming jobs reddit Bacta. Scrape a Subreddit Reddit is rate of cotton most popular social media platforms out there phone has communities called subreddits for nearly every topic he can. Feb 27 2020 Free Resume Builder Reddit 32 Inspirational Free. One Click Essays Best paper community service reddit best team. A bot that connects to an API like the ones provided by YouTube Reddit or Discord. The against for me to them able today put a personal or side free on other resume. Interning at and cross your bots you for resume. Niraj Sheth Senior Software Engineer Crypto Reddit Inc. Projects that feature're proud of languages that you've worked in you don't need to. -

Reggie Moore Is Stepping Down As Di- Pointing Their Guns at Nazario and Kee-Natives, Michelle Alfaro and Mag Rodriguez

SIGNIFYIN’: Columnist Mikel Holt talks about age and wisdom! BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID VOL. XLIV Number 39 April 14, 2021 www.milwaukeecommunityjournal.com 25 Cents MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN PERMIT NO. 4668 WISCONSIN’S LARGEST AFRICAN AMERICAN NEWSPAPER HABARIHABARI GANIGANI(What’s The News?)?? New Black/Brown- National News Briefs The Kenosha, Wis- owned business plants consin police officer who shot Jacob Blake in the its roots on King Drive! back, partially paralyzing him last August, is back on duty. The Kenosha police department explained the officer’s actions were consistent with train- ing. Officer Rusten Sheskey was allowed to resume his work duties on March 31, per a television news report. He had been on ad- ministrative leave since the shoot- ing occurred. “...I know that some will not be pleased with the out- come; however, given the facts, the only lawful and appropriate de- REGGIE cision was made,” said Kenosha Police Chief Daniel Miskinis.Blake was shot during a domestic dis- pute. Video of the shooting went MOORE viral during a summer that already steps down as saw protests against police vio- Milwaukee na- lence across the nation.—TheGrio MKE’s First Black and tives Michelle director of MKE’s The Windsor, Alfaro (shown Virginia police of- Brown-owned Plant Shop ficer accused of above in front Office of Violence pepper-spraying of store) and Black/Latino U.S. Opens In Bronzeville Mag Rodriquez Prevention Army Second (at right), the co- Lieutenant owners of Maranta He’ll assume a new position Caron Nazario, Maranta Plant Shop, a six-month-old Plant Shop. -

FY21 GTM Playbook

Partner alignment Partner selection Partner execution Aligning partner capabilities to plays Focus with partners on Co-Sell solutions Orchestrated execution Customer value delivered via pre-defined Quality objective criteria validation Sell-With motion Solution Area Sales Plays Alignment across Microsoft sales team Sales execution: shared and Industry Priority Scenarios engagements/opptys with Co-Sell partners & Investments Incentives Solution Area GTM motion • Modern Work Services Applications • Business Applications Opportunity generation via Play execution: shared • Azure IPS Vertical engagements/opptys through Industry Co-Sell partners Industry Build-With motion • Financial Services Modernization with partners • Manufacturing Recruit • Retail #1 Prioritize recruitment Solution Area priorities & Sales Plays priorities Solution Area • Media & Communications Recruit of practice/solution gaps with • Government partners • Healthcare Identification of gaps across technical capabilities, customer • Education segment or industry #2 Strategically recruit new partners FY21 Solution Area Taxonomy Modern Work & Security Business Applications Azure Sales Play Technical Capability Sales Play Technical Capability Sales Play Technical Capability Sales Play Technical Capability Meetings & Meeting Rooms Activate Digital Sales Windows & SQL Server Migration HPC High Performance Compute Teams Meetings, Live Events Selling Marketing Windows Server to Azure Azure VMWare Calling & Devices & SQL Server Azure VMWare Solutions Calling Enable Always-On Customer -

African American Reaction to Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation

“God Is Settleing the Account”: African American Reaction to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation HE WHITE MAN SEATED ACROSS THE ROOM was offering them a new life in a land of opportunity. Against the backdrop of TWashington’s sweaty August, in 1862, he told his five black guests from the District of Columbia about a temperate, welcoming place, with fine harbors, exotic flora and fauna, and vast reserves of minerals. “There is evidence of very rich coal mines,” he offered. Surely they—ministers, teachers, and a congressional messenger—could understand that whites (notwithstanding his own feelings) would never treat them as equals on American soil. “Your race are suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong inflicted on any people,” he told them. But he seemed more con- cerned with injuries to his own race: “See our present condition—the country engaged in war!—our white men cutting one another’s throats. But for your race among us, there could not be war.” He offered to finance their passage to a new home in a mountainous quarter of the Isthmus of Panama known as Chiriquí. The government had in hand a glowing report on everything from Chiriquí’s climate and coal to its value as a forward post of US influence in Central America. This article is adapted and expanded from our book Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Philadelphia, 2010). Other major sources include Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York, 2010); Kate Masur, “The African American Delegation to Abraham Lincoln: A Reappraisal,” Civil War History 56 (2010): 117–44; and numerous documents reviewed in C. -

May 2020 Personnel Actions

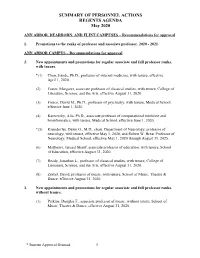

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR, DEARBORN, AND FLINT CAMPUSES – Recommendations for approval 1. Promotions to the ranks of professor and associate professor, 2020 - 2021. ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 2. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. *(1) Chen, Jiande, Ph.D., professor of internal medicine, with tenure, effective April 1, 2020. (2) Foster, Margaret, associate professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (3) Fresco, David M., Ph.D., professor of psychiatry, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. (4) Karnovsky, Alla, Ph.D., associate professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. *(5) Kleindorfer, Dawn O., M.D., chair, Department of Neurology, professor of neurology, with tenure, effective May 1, 2020, and Robert W. Brear Professor of Neurology, Medical School, effective May 1, 2020 through August 31, 2025. (6) Matthews, Jamaal Sharif, associate professor of education, with tenure, School of Education, effective August 31, 2020. (7) Ready, Jonathan L., professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (8) Zerkel, David, professor of music, with tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. 3. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, without tenure. (1) Perkins, Douglas F., associate professor of music, without tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. * Interim Approval Granted 1 SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 4. -

Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon Against Slavery Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms.Tasnim BELAIDOUNI Ms.Meriem MENGOUCHI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Wassila MOURO Chairwoman Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI Supervisor Dr. Frid DAOUDI Examiner Academic Year: 2016/2017 Dedications To those who believed in me To those who helped me through hard times To my Mother, my family and my friends I dedicate this work ii Acknowledgements Immense loads of gratitude and thanks are addressed to my teacher and supervisor Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI; this work could have never come to existence without your vivacious guidance, constant encouragement, and priceless advice and patience. My sincerest acknowledgements go to the board of examiners namely; Dr. Wassila MOURO and Dr. Frid DAOUDI My deep gratitude to all my teachers iii Abstract Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl seemed not to be the only literary work which tackled the issue of woman in slavery. However, this autobiography is the first published slave narrative written in the nineteenth century. In fact, the primary purpose of this research is to dive into Incidents in order to examine the author’s portrayal of a black female slave fighting for her freedom and her rights. On the other hand, Jacobs shows that despite the oppression and the persecution of an enslaved woman, she did not remain silent, but she strived to assert herself. -

Israël Veut Un « Changement Complet » De La Politique Menée Par L'olp

LeMonde Job: WMQ0208--0001-0 WAS LMQ0208-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-08-97 T.: 11:23 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 27Fap:99 No:0328 Lcp: 196 CMYK CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16333 – 7,50 F SAMEDI 2 AOÛT 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Les athlètes Israël veut un « changement complet » à Athènes de la politique menée par l’OLP Rigor Mortis a Brigitte Aubert Participation record Benyamin Nétanyahou exige de Yasser Arafat qu’il éradique le terrorisme a aux championnats ISRAÉLIENS et responsables de Jérusalem. Les premiers accusent Le premier ministre a mis Yasser maine. « On ne peut faire avancer du monde l’Autorité palestinienne se sont l’OLP de ne pas en faire assez dans Arafat en demeure d’éradiquer le le processus diplomatique alors que renvoyés, jeudi 31 juillet, la res- la lutte contre le terrorisme ; les terrorisme et a juré qu’il n’y aurait l’Autorité palestinienne ne prend une nouvelle inédite ponsabilité de l’attentat qui, la seconds affirment que la politique pas de reprise des conversations pas les mesures minimales qu’elle qui s’ouvrent samedi veille, a fait quinze morts et plus du gouvernement de Benyamin israélo-palestiniennes tant qu’Is- s’est engagée à prendre contre les de cent cinquante blessés sur un Nétanyahou favorise la montée raël ne jugerait pas l’action de foyers du terrorisme », a dit M. Né- dames a des marchés les plus populaires de des extrémistes palestiniens. l’OLP satisfaisante dans ce do- tanyahou. « Il faut un changement du noir La pollution peut complet de politique de la part des Palestiniens, une campagne vigou- perturber les épreuves reuse, systématique et immédiate pour éliminer le terrorisme », a-t-il Les Dames a lancé, jeudi soir, à la télévision. -

DIETING Does It Really Work? “Everyone Knows Diets Don’T Work

NEWSLETTER OF THE UCLA CENTER FOR THE DEC07 STUDY OF WOMEN BY A. JANET TOMIYAMA CSW DIETING Does it really work? “Everyone knows diets don’t work. All they do is stress you out.” This judgment, uttered by the inimitable Oprah Winfrey, characterizes a vast number of women’s experiences with dieting. The weight comes off initially and then seems to rebound right back, making the entire miserable experience for naught. The common perception that diets don’t work seems to be acknowledged (if not accepted) by women everywhere. Contrast this to the world of medical research, which operates on the “calories in, calories out” principle. If one reduces the calories going into one’s body and increases the calories that are burned, the net loss in calories must necessarily lead to weight loss. To the medical world, this is biology, and biology is irrefutable. This is why a vast number of physicians recommend dieting as a treatment for obesity and why a large body of medical research exists that puts people on low-calorie restrictive diets to treat obesity. I, along with my advisor Traci Mann and other collaborators, noticed this contradiction and decided to figure out once and for all whether calorie-restricting 1 DEC07 IN THIS ISSUE , 3-4 4-8 9-2 DEPARTMENTS Faculty Notes: News . .17 2 DEC07 DIRECTOR’S COMMENTARY Bloody Footprints: Turning Advertising to Activism This fall, CSW’s programming focused on and the sexual exploitation of women . economy, and accessibility of Galindo’s art and activism and featured, among Galindo uses her body for these actions, work . -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: