2010 Social and Affective Neuroscience Conference Schedule‐At‐A‐Glance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness and the 12 Steps

mindfulness and the 12 steps with Thérèse Jacobs-Stewart Resting the Mind • Assume a body position where your spine is straight and your body relaxed. • Allow your mind to rest for a few minutes, letting whatever happens-or doesn’t happen-be a part of the experiment. • Relax with whatever arises. • When time is up, ask yourself, “How was that?” (Don’t judge; just review what happened and how you felt.) • The only difference between meditation and the ordinary process of feeling, thinking, feeling, and sensation is the application of the “bare awareness.” Mindfulness Meditation Consciously bring awareness to your here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and self-acceptance. 1 Ways Mindfulness and Meditation Help the Therapist • Offers idea of “strengthening the heart” vs. western psychology’s concept of “self-care.” • Reduces compassion fatigue, renews energy, and counteracts burn-out. • Deepens capacity for a compassionate and non- judging presence. • Increases ability to abide with difficult emotions, offering hope and relief. • Sharpens awareness of therapist’s own reactions. Specific Brain States Correlate with Happiness Brain Activity Associated with Mindfulness Meditation 2 Meditation Changes the Circuitry of the Brain Jacobs-Stewart, Paths Are Made by Walking, 2003 “Meditation training can change the brain and forever alter our sense of well-being.” Richard Davidson Laboratory for Neuroaffective Science University of Wisconsin, Madison 3 Effects of Mindfulness on the Addictive Brain • Enhances neural plasticity. • Reduces activity in the amygdala. • Thickens the bilateral, prefrontal right-insular region of the brain. • Integrates prefrontal regulation and limbic emotion activation. • Builds new neural connections among brain cells for self-observation, optimism, and well-being. -

Reviewers Who Completed a Review During 2001

REVIEWERS LIST The constituency of the ARCHIVES comprises a “university” of often interchangeable writers and readers, students, knowledgeable practitioners, and scholars of medicine and sciences underlying the field of psychiatry. The editors are deeply grateful to the many colleagues listed here for their generous assistance in editorial critique and review. The donation of their special expertise is a necessary contribution on which the intellectual standards in the field heavily depend. Jack D. Barchas, MD Editor Larry Abel Francesc Artigas Chawki Benkelfat Evelyn Bromet James Abelson Robert Asarnow Lisa Berkman Judith S. Brook Anissa Abi-Dargham Wesson Ashford Karen Faith Berman Robert K. Brooner Howard B. Abikoff Boris Astrachan Robert Berman George W. Brown Lyn Y. Abramson Evelyn Attia Greg Berns Marty Bruce T. M. Achenbach S. Avenevoli Wade Berrettini Gerard E. Bruder Kenneth M. Adams Elizabeth Auchincloss Larry E. Beutler Maja Bucan Lawrence E.Adler David Avery Joseph Biederman Robert W. Buchanan Lenard A. Adler Thomas Babor Laura Bierut Kathleen K. Bucholz Nancy E. Adler Nadia Badawi George Bigelow Monte Buchsbaum Ralph Adolphs Alan D. Baddeley Robert Bilder Alan J. Budney George Aghajanian Lee Baer Rene Binder Stephen L. Buka W. Stewart Agras J. Michael Bailey Ray Bingham William E. Bunney Schahram Akbarian Ross J. Baldessarini Niels Birbaumer Audrey Burnam Huda Akil James C. Ballenger Boris Birmaher Barbara J. Burns Hagop S. Akiskal J. Bancroft Donald Black Terry Bush Claude Alain Karen J. Bandeen-Roche D. H. Blackwood Daniel Buysse Marigarita Alegria Deanna M. Barch Jack Blaine William Byne Georgios Alexopoulos John C. Barefoot Helen Blair Simpson Robert P. Cabaj Kimmo Alho Russell A. -

Meghan L. Meyer, Ph.D

Meghan L. Meyer, Ph.D. Department of Psychology | University of California-Los Angeles Email: [email protected] | Phone: 650.521.1701 Web: http://meghanlmeyer.com EDUCATION 2008-2014 University of California-Los Angeles Ph.D. Social Psychology Minors: Quantitative Psychology & Cognitive Neuroscience Advisor: Dr. Matthew Lieberman 2004-2006 École Normale Supérieure M.A. Cognitive Science Specialty: Cognitive Neuroscience Advisor: Dr. Jean Decety 2001-2004 Emory University, B.A. Psychology EMPLOYMENT 6/2014-Present Postdoctoral Scholar Department of Psychology University of California-Los Angeles 2006-2008 Research Assistant Stanford University Stanford Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience Lab Principal Investigator, Dr. Vinod Menon FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS and AWARDS 2014 Shelley E. Taylor Dissertation Award, UCLA Psychology 2013 International Cultural Neuroscience Consortium (ICNC) Travel Award 2012 Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA, Predoctoral, National Institutes of Health-NIMH 2012 Harold H. Kelley Award for Best Basic Science Research Paper, UCLA 2012 UCLA Advanced Neuroimaging Summer Training Fellowship 2011 fMRI Training Course Fellowship, University of Michigan 2011, 2009 UCLA Graduate Summer Research Mentorship Fellowship 2010 National Science Foundation EAPSI Fellow 2008 University Graduate Fellowship-UCLA PUBLICATIONS Spunt, R. P., Meyer, M. L., & Lieberman, M. D. (in press). The default mode of human brain function primes the intentional stance, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Meyer, M. L., Masten, C. L., Ma, Y., Wang, C., Shi, Z., Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D. & Han, S. (in press). Differential neural activation to friends and strangers links interdependence to empathy. Culture & Brain. Tabak, B. A., Meyer, M. L., Castle, E., Dutcher, J., Irwin, M. R., Lieberman, M. D., & Eisengerger, N. I., (in press). -

Putting Feelings Into Words Affect Labeling Disrupts Amygdala Activity in Response to Affective Stimuli Matthew D

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article Putting Feelings Into Words Affect Labeling Disrupts Amygdala Activity in Response to Affective Stimuli Matthew D. Lieberman, Naomi I. Eisenberger, Molly J. Crockett, Sabrina M. Tom, Jennifer H. Pfeifer, and Baldwin M. Way University of California, Los Angeles ABSTRACT—Putting feelings into words (affect labeling) physical health (Hemenover, 2003; Pennebaker, 1997). Al- has long been thought to help manage negative emotional though conventional wisdom and scientific evidence indicate experiences; however, the mechanisms by which affect that putting one’s feelings into words can attenuate negative labeling produces this benefit remain largely unknown. emotional experiences (Wilson & Schooler, 1991), the mecha- Recent neuroimaging studies suggest a possible neuro- nisms by which these benefits arise remain largely unknown. cognitive pathway for this process, but methodological Recent neuroimaging research has begun to offer insight into limitations of previous studies have prevented strong in- a possible neurocognitive mechanism by which putting feelings ferences from being drawn. A functional magnetic reso- into words may alleviate negative emotional responses. A nance imaging study of affect labeling was conducted to number of studies of affect labeling have demonstrated that remedy these limitations. The results indicated that affect linguistic processing of the emotional aspects of an emotional labeling, relative to other forms of encoding, diminished image produces less amygdala activity than perceptual pro- the response of the amygdala and other limbic regions cessing of the emotional aspects of the same image (Hariri, to negative emotional images. Additionally, affect labeling Bookheimer, & Mazziotta, 2000; Lieberman, Hariri, Jarcho, produced increased activity in a single brain region, right Eisenberger, & Bookheimer, 2005). -

An Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION

Thought Without Language: an Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Dean Jaworski Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Neil Tennant, Advisor William Taschek Ben Caplan Copyright by Michael Dean Jaworski 2010 Abstract I defend an account of thought on which non-linguistic beings can be thinkers. This result is significant in that many philosophers have claimed that the ability to think depends on the ability to use language. These opponents of my view note that our everyday understanding of our own cognitive activities qua thought bestows upon those activities the propositional structure of sentences and the inferential norms of public linguistic practice. They hold that our attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings project non-existent structure onto the cognitive activities of those beings, and assess the beings’ activities according to standards to which the beings bear no responsibility. So, despite the complex neural and behavioral activities of many non-linguistic beings, my opponents hold that those beings are not properly described as thinkers. To respond to my opponents successfully, one must not merely cite scientific and folk practices of thought attribution that permit thought to be attributed to some non- linguistic beings. My opponents’ insights might be taken to demonstrate a need to revise those practices, or to treat the attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings made within those practices as instrumentally valuable but technically false. Instead, my strategy is to acknowledge the language-like structure and norms of thought, and show that a non- linguistic being’s cognitive activities might nonetheless have that structure and be subject ii to those norms. -

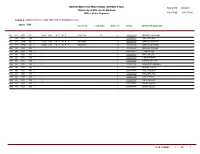

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM SUBJECT: AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMICS (108) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME AGRICULTURALALS AND APPLIED ECONOMICS ACC 306 LEC 001 1 09:00 - 12:00 M T W R 0140 1185 49 6 0000875079 MICHAEL JOHNSON DJJ 399 IND 086 1 - 2 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL ECC 875 SEM 001 2 13:00 - 16:00 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON ECC 875 SEM 001 1 08:30 - 11:30 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON DHH 990 IND 063 1 - 9 0000226384 MICHAEL CARTER DHH 990 IND 064 1 - 1 0002600175 THOMAS COX DHH 990 IND 073 1 - 3 0002601457 IAN COXHEAD DHH 990 IND 078 1 - 3 0002602152 T FORTENBERY DHH 990 IND 079 1 - 1 0002600972 STEVEN DELLER DHH 990 IND 080 1 - 3 0002602096 BRADFORD BARHAM DHH 990 IND 082 1 - 2 0000125075 JEREMY FOLTZ DHH 990 IND 083 1 - 6 0003374884 KYLE STIEGERT DHH 990 IND 086 1 - 1 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL DHH 990 IND 087 1 - 3 0004111956 DAVID LEWIS DHH 990 IND 089 1 - 1 0001459007 SHI GUANMING DHH 990 IND 090 1 - 1 0001016452 BRENT HUETH DHH 999 IND 085 1 - 1 0003088634 BRIAN GOULD PAGE NUMBER: 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:44:48AM SUBJECT: BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING (112) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING DHH 399 IND 010 1 - 2 0000693634 DAVID BOHNHOFF DHH 399 IND 014 1 - 2 0000664097 -

Empathy: a Social Cognitive Neuroscience Approach Lian T

Social and Personality Psychology Compass 3/1 (2009): 94–110, 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00154.x Empathy: A Social Cognitive Neuroscience Approach Lian T. Rameson* and Matthew D. Lieberman Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There has been recent widespread interest in the neural underpinnings of the experience of empathy. In this review, we take a social cognitive neuroscience approach to understanding the existing literature on the neuroscience of empathy. A growing body of work suggests that we come to understand and share in the experiences of others by commonly recruiting the same neural structures both during our own experience and while observing others undergoing the same experience. This literature supports a simulation theory of empathy, which proposes that we understand the thoughts and feelings of others by using our own mind as a model. In contrast, theory of mind research suggests that medial prefrontal regions are critical for understanding the minds of others. In this review, we offer ideas about how to integrate these two perspectives, point out unresolved issues in the literature, and suggest avenues for future research. In a way, most of our lives cannot really be called our own. We spend much of our time thinking about and reacting to the thoughts, feelings, intentions, and behaviors of others, and social psychology has demonstrated the manifold ways that our lives are shared with and shaped by our social relationships. It is a marker of the extreme sociality of our species that those who don’t much care for other people are at best labeled something unflattering like ‘hermit’, and at worst diagnosed with a disorder like ‘psychopathy’ or ‘autism’. -

John T. Cacioppo

Although the quantitative logic and formal proofs of economics were appealing, the emphasis on forecasting rather than on delineating underlying mechanisms was less so. A serendipitous meeting with Lee Becker, a social psy- chologist at the University of Missouri, led Cacioppo to the medical school, where he conducted his first study combin- ing physiological and social measures in investigating a psychological question. Cacioppo abandoned his plans to pursue a career in law and instead went to graduate school in social psychology at Ohio State University. Cacioppo’s mentors at Ohio State included Tony Green- wald, Tim Brock, Bob Cialdini, and John Harvey. Ca- cioppo also continued his studies of psychobiology and psychophysiology, working primarily with Curt Sandman with occasional but always memorable visits to John and broadly. Bea Lacey at the nearby Fels Research Institute in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Perhaps the most influential person he met publishers. at Ohio State, however, was another first-year graduate student, Richard Petty. By the end of their first week in allied disseminated its graduate school, Cacioppo and Petty were arguing in- be of tensely about everything. To save money, they rented a to one John T. Cacioppo dilapidated house and covered an entire wall with black- not or is Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions board paint to work through their various arguments. These and experiences drove home two points that have shaped Ca- cioppo’s thinking for the remainder of his career. First, user Citation Association complex social behaviors have multiple antecedents within “For his pioneering research within social psychology and and across levels of organization; as such, comprehensive within psychophysiology, and especially for bringing these individual accounts of social cognition, emotion, and behavior require worlds together. -

PSYCHOLOGY SELF-STUDY 2010 Table of Contents Page A. Department Overall Mission and Goals…………………………………

PSYCHOLOGY SELF-STUDY 2010 Table of Contents Page A. Department Overall Mission and Goals…………………………………………………………………………………….x B. The Faculty 1. Organization, Size, Demographics. 2. Faculty Quality 3. Faculty Workload and Assessment 4. Faculty Retention and Compensation 5. Interdisciplinary Connections C. Departmental Governance, Infrastructure, and the Staff 1. Departmental Governance 2. Departmental Staff 3. Departmental Buildings, Equipment, and Infrastructure D. The Undergraduate Program 1. The Undergraduate Major 2. The Undergraduate Minor 3. The Honors Program 4. Recent Curricular Changes 5. Psychology 100 6. Role of Technology and the Major Fee 7. Faculty, Lecturer, and Graduate Student Teaching Mix 8. Unique Undergraduate Programs 9. Student Outcomes Assessment 10. Directions for the Future E. The Graduate Program 1. Overview 2. Curriculum 3. Program Size 4. Student Quality 5. Graduate Recruitment 6. Attrition and Time to Degree 7. Academic Life of the Department 8. Placements 9. Student Diversity 10. Student Support 11. Summary F. Graduate Program Areas G. Overall Departmental Strengths, Challenges, and Priorities 1. Undergraduate Program 2. Graduate Program 3. Departmental Faculty Hiring Plans 4. Cross Area and Interdisciplinary Connections 5. Diversity 6. Summary of Priorities List of Tables in Document 1. Proportion of Current Male, Female and Minority Psychology Faculty at Each Rank 2. Comparison of Initial Placements of Ph.D. Graduates (2006-2007) 3. Distribution of OSU Psychology Students by Race and Ethnicity Compared to National Averages 4. Most Recent 5 Year Admission Data for All Graduate Program Areas 5. Ten Year First Job Placement Data for Graduate Program Areas 6. Interviewees in Psychology Searches (2008-2010) List of Figures in Document 1. -

Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2018 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness Peter H. Huang University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Citation Information Peter H. Huang, Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness, 7 BRIT. J. AM. LEGAL STUD. 425 (2018), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1237. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 7(2) (2018), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2018-0008 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, And Mindfulness Peter H. Huang* ABSTRACT Spis treści This Article recounts my unique adventures in higher education, including being a Princeton University freshman mathematics major at age 14, Harvard University applied mathematics graduate student at age 17, economics and finance faculty at multiple schools, first-year law student at the University of Chicago, second- and third-year law student at Stanford University, and law faculty at multiple schools. -

Npp2013281.Pdf

Neuropsychopharmacology (2013) 38, S435–S593 & 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/13 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session III-Wednesday participants indicated their ongoing experience of the Wednesday, December 11, 2013 intensity of heartbeat and breathing sensations by rotating a dial. Discrimination was measured by a positive dial deflection above baseline during an infusion trial. Accuracy W2. Interoceptive Awareness in Meditators During was measured via maximum cross correlation between each Cardiorespiratory Deviations in Body Arousal subject’s dial ratings and their corresponding heart rate Sahib Khalsa*, David Rudrauf, Richard Davidson, response. After each infusion participants also traced the Daniel Tranel body locations where they had felt heartbeat sensations, on a manikin template. UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Results: Bolus isoproterenol infusions elicited equivalent Behavior, Los Angeles, California increases in heart rate in both groups (Repeated measures ANOVA; F(1, 5) ¼ 50.1, po0.0001). There were no signifi- Background: Attention directed towards internal body cant group (F(1, 28) ¼ 1.27, p ¼ 0.27) or group x dose sensations is commonly practiced in many meditation interactions (F(1, 5) ¼ 0.04, p ¼ 0.998). There were also no traditions, and is a core skill cultivated when learning group differences in adrenergic sensitivity as measured by mindfulness. This practice is commonly proposed to CD25 (dose required to elevate heart rate by 25 beats per -

Willis and the Virtuosi

Forum on Public Policy The Scientific Method through the Lens of Neuroscience; From Willis to Broad J. Lanier Burns, Professor, Research Professor of Theological Studies, Senior Professor of Systematic Theology, Dallas Theological Seminar Abstract: In an age of unprecedented scientific achievement, I argue that the neurosciences are poised to transform our perceptions about life on earth, and that collaboration is needed to exploit a vast body of knowledge for humanity’s benefit. The scientific method distinguishes science from the humanities and religion. It has evolved into a professional, specialized culture with a common language that has synthesized technological forces into an incomparable era in terms of power and potential to address persistent problems of life on earth. When Willis of Oxford initiated modern experimentation, ecclesial authorities held intellectuals accountable to traditional canons of belief. In our secularized age, science has ascended to dominance with its contributions to progress in virtually every field. I will develop this transition in three parts. First, modern experimentation on the brain emerged with Thomas Willis in the 17th Century. A conscientious Anglican, he postulated a “corporeal soul,” so that he could pursue cranial research. He belonged to a gifted circle of scientifically minded scholars, the Virtuosi, who assisted him with his Cerebri anatome. He coined a number of neurological terms, moved research from the traditional humoral theory to a structural emphasis, and has been remembered for the arterial structure at the base of the brain, the “Circle of Willis.” Second, the scientific method is briefly described as a foundation for understanding its development in neuroscience.