Edited and Approved Screenwriting the Euro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: March 23, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Mauli Singh [email protected] Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48 Lab Recognizes and Supports Six Emerging Independent Filmmakers from India Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute and Drishyam Films today announced the artists and creative advisors selected for the second Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48. The Lab supports emerging filmmakers in India, as part of the Institute’s sustained commitment to international artists, which in the last 25 years has included programs in Brazil, Mexico, Jordan, Turkey, Japan, Cuba, Israel and Central Europe. Now in its second year, the fourday Lab is a creative and strategic partnership between Drishyam Films and Sundance Institute, and gives independent screenwriters the opportunity to work intensively on their feature film scripts in an environment that encourages innovation and creative risktaking. The Lab is centered around oneonone story sessions with creative advisors. Screenwriting fellows engage in an artistically rigorous process that offers lessons in craft, a fresh perspective on their work and a platform to fully realize their material. Leading the Lab in India is Drishyam founder, Manish Mundra. He said, “A beautiful heritage city in my hometown of Rajasthan, Udaipur forms an ideal writers retreat, and is the perfect environment for a diverse group of emerging writers and renowned mentors to have a refreshing and productive exchange. Our goal is that the six selected Indian projects, after undergoing a comprehensive mentoring process, will quickly move from script to screen and make their mark globally. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Cedric Jimenez

THE STRONGHOLD Directed by Cédric Jimenez INTERNATIONAL MARKETING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY Alba OHRESSER Margaux AUDOUIN [email protected] [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Marseille’s north suburbs hold the record of France’s highest crime rate. Greg, Yass and Antoine’s police brigade faces strong pressure from their bosses to improve their arrest and drug seizure stats. In this high-risk environment, where the law of the jungle reigns, it can often be hard to say who’s the hunter and who’s the prey. When assigned a high-profile operation, the team engages in a mission where moral and professional boundaries are pushed to their breaking point. 2 INTERVIEW WITH CEDRIC JIMENEZ What inspired you to make this film? In 2012, the scandal of the BAC [Anti-Crime Brigade] Nord affair broke out all over the press. It was difficult to escape it, especially for me being from Marseille. I Quickly became interested in it, especially since I know the northern neighbourhoods well having grown up there. There was such a media show that I felt the need to know what had happened. How far had these cops taken the law into their own hands? But for that, it was necessary to have access to the police and to the files. That was obviously impossible. When we decided to work together, me and Hugo [Sélignac], my producer, I always had this affair in mind. It was then that he said to me, “Wait, I know someone in Marseille who could introduce us to the real cops involved.” And that’s what happened. -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

Educational Newsletter

Educational Newsletter http://campaign.r20.constantcontact.com/render?llr=zg5n4wcab&v=001K... The content in this preview is based on the last saved version of your email - any changes made to your email that have not been saved will not be shown in this preview. February 2012 Educational Newsletter French Consulate in Boston Our Academic News In This Issue Formation pour professeurs de français Offre de formation "Réaliser une "Voyages en Francophonie" production audiovisuelle" Our 2011 Contest! Nous avons la possibilité de faire SPCD Grant intervenir à Boston un formateur du The Green Connection Centre de liaison de l'enseignement et des médias d'information (CLEMI) sur le CampusArt thème suivant : "Réaliser une production Hewmingway Grant Program audiovisuelle en classe de français langue étrangère" (détails ICI ). Elle La FEMIS pourrait accueillir une trentaine de Merrimack College Language professeurs de middle schools et high schools. La formation se Programs déroulerait sur deux fois 3 heures en "afterschool" les 27 et 28 "Voyages en Francophonie" février, ou le 28 février sur 6 heures en journée (il est possible de n'assister qu'à la première session, mais en faisant l'impasse Printemps des Poètes sur la partie pratique). Tous les frais sont pris en charge par les "A Preview of 2012 in France" services culturels de l'ambassade de France. Si cette formation Clermont-Ferrand International Short intéresse un nombre suffisant d'entre vous, nous serions Film Festival heureux de l'organiser. Dans ce cas, merci de le faire savoir rapidement à Guillaume Prigent compte tenu des délais très Providence French Film Festival courts. -

JUMBO DUMBO Witnesses’ Four Towers Will Double Population

SATURDAY • MAY 15, 2004 Including Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, Downtown News, DUMBO Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 18 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 27, No. 19 BWN • Saturday, May 15 2004 • FREE JUMBO DUMBO Witnesses’ four towers will double population By Deborah Kolben 1,500 residents. The Watchtow- anything that the neighborhood / Jori Klein The Brooklyn Papers er buildings would house about needs,” she said, adding that she 2,000 more. is also concerned about the in- The DUMBO neighbor- The religious organization, creased traffic the development hood, known for artist stu- whose world headquarters al- will bring. dios, stunning Manhattan The Department of The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn views and relatively unclut- City Planning has been tered streets, may soon NOT JUST NETS working with the more than double its resi- THE NEW BROOKLYN Watchtower Society Hannah Yagudina, 10, laughs with Tangerine the Clown on Wednesday at John J. Pershing Intermediate School. Chronically ill children and their fami- dential population. for the past year and a lies gathered at the school for an evening of games, celebrity guests and gifts through the Kids Wish Network “Holiday of Hope” program. The Watchtower Bible and half to develop an ap- Tract Society, commonly known ready lies at the neighborhood’s propriate design for the build- as the Jehovah’s Witnesses reli- perimeter, owns the three acre ings half a block from the Man- gious order, is expected within site. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

Press Information September | October 2016 Choice of Arms The

Press Information September | October 2016 Half a century of modern French crime thrillers and Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton 's collaboration of the century in the year of 1965; the politically aware work of documentary filmmaker Helga Reidemeister and the seemingly apolitical "hipster" cinema of the Munich Group between 1965 and 1970: these four topics will launch the 2016/17 season at the Austrian Film Museum. Furthermore, the Film Museum will once again take part in the Long Night of the Museums (October 1); a new semester of our education program School at the Cinema begins on October 13, and the upcoming publications ( Alain Bergala's book The Cinema Hypothesis and the DVD edition of Josef von Sternberg's The Salvation Hunters ) are nearing completion. Latest Film Museum restorations are presented at significant film festivals – most recently, Karpo Godina's wonderful "film-poems" (1970-72) were shown at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna – the result of a joint restoration project conducted with Slovenska kinoteka. As the past, present and future of cinema have always been intertwined in our work, we are particularly glad to announce that Michael Palm's new film Cinema Futures will have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 2 – the last of the 21 projects the Film Museum initiated on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2014. Choice of Arms The French Crime Thriller 1958–2009 To start off the season, the Film Museum presents Part 2 of its retrospective dedicated to French crime cinema. Around 1960, propelled by the growth spurt of the New Wave, the crime film was catapulted from its "classical" period into modernity. -

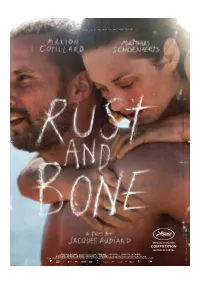

Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND

RustnBone1.indd 1 6/5/12 15:12:51 Why Not Productions and Page 114 present Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND BONE A film by Jacques Audiard Armand Verdure / Céline Sallette / Corinne Masiero Bouli Lanners / Jean-Michel Correia France / Belgium / 2012 / color / 2.40 / 120 min International Press: International Sales: Magali Montet Celluloid Dreams [email protected] 2, rue Turgot - 75009 Paris Tel: +33 6 71 63 36 16 Tel: +33 1 4970 0370 Fax: +33 1 4970 0371 Delphine Mayele [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +33 6 60 89 85 41 Contact in Cannes Celluloid Dreams 84, rue d’Antibes 06400 Cannes Hengameh Panahi +33 6 11 96 57 20 Annick Mahnert +33 6 37 12 81 36 Agathe Mauruc +33 6 82 73 80 04 Director’s Note There is something gripping about Craig Davidson’s short story collection “Rust and Bone”, a depiction of a dodgy, modern world in which individual lives and simple destinies are blown out of all proportion by drama and accident. They offer a vision of the United States as a rational universe in which the physical needs to fight to find its place and to escape what fate has in store for it. Ali and Stephanie, our two characters, do not appear in the short stories, and Craig Davidson’s collection already seems to belong to the prehistory of the project, but the power and brutality of the tale, our desire to use drama, indeed melodrama, to magnify their characters all have their immediate source in those stories. -

Le Festival Aura Bien Lieu

SAMEDI 10 OCTOBRE Le journal du Festival « Va voir au 3. Le client de Maurice fait du schproum pour l’addition » Michel Audiard, Le Désordre et la nuit #01 Ça commence ! Ce douzième festival Lumière s’ouvre dans le contexte particulier que traversent Lyon, notre pays et le monde tout entier. C’est dire à quel point il nous tient à cœur que cette manifestation soit riche, diverse et festive. Prudemment festive, bien sûr, dans le respect des gestes auxquels nous nous habituons peu à peu. Mais avec son lot de découvertes, d’enthousiasmes et d’échanges (masqués) avec les artistes qui, comme chaque année, viendront partager leur passion et leurs créations. Plus que jamais le cinéma et l’art en général doivent nous permettre de surmonter les crises, de mieux comprendre le monde et d’aider à le réparer – ce pourrait être le credo de Jean-Pierre et Luc Dardenne, observateurs incisifs de nos sociétés, qui recevront cette JOUR J ! année le Prix Lumière. Dans l’obscurité des salles, le partage d’une émotion, rire, peur ou tristesse, sera la victoire quotidienne de l’imaginaire sur le réel. Cette année, nous serons tous prudents et responsables, mais LE FESTIVAL toujours aussi curieux, attentifs et émerveillés. Soyez les bienvenus ! AURA BIEN LIEU L’équipe du festival ©Jean-Luc Mège CENTENAIRE POLÉMISTE Audiard, ©DR sacré Carrément grand-père Stone Il publie son autobiographie, A la recherche ©DR de la lumière et présente Né un quatre juillet. Dans la famille Audiard, on demande Stéphane, amateur des films de son grand-père. Oliver Stone revient aux racines de son Il raconte le Michel Audiard intime, énorme bosseur et panier percé. -

A Film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

A film by MICHAEL HANEKE East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Lindsay Macik 853 7th Avenue, #3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) A film by MICHAEL HANEKE A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE US RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 30, 2009 Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 www.TheWhiteRibbonmovie.com Q & A WITH MICHAEL HANEKE Q: What inspired you to focus your story on a village in Northern Germany just prior to World War I? A: I wanted to present a group of children on whom absolute values are being imposed. What I was trying to say was that if someone adopts an absolute principle, when it becomes absolute then it becomes inhuman. The original idea was a children’s choir, who want to make absolute principles concrete, and those who do not live up to them. Of course, this is also a period piece: we looked at photos of the period before World War I to determine costumes, sets, even haircuts. I wanted to describe the atmosphere of the eve of world war. There are countless films that deal with the Nazi period, but not the pre-period and pre-conditions, which is why I wanted to make this film. -

Oscar Nominations About "Kagemusha"

Free TWT MAGAZINE . Texas' Leaqing Goy Publication Volume 6, Number 49 February 27 - March 5, 1981 OSCAR NOMINATIONS ABOUT "KAGEMUSHA" WELCOMING ALL RODEO FANS TO THE SUNDAY SHOW FREE BEER 8·1Q1t, PM BEF.ORE SHOW 2631 Richmond WELCOMING Houston NEW MANAGER 911 West Drew (comer of Jackson Blvd. and Grant) Houston 528-9261 528-2259 MARK WILLIAMSON TWT FEORUAIW27 -MARCH 5,1981 PAGE 4 1WTFEORUARY27 - MARCH 5, 1981 PAGE 5 \WI l CONTENTS __ Volume 6, Number 49 Februory 27 - Morch 5, 1981 9 TWT NEWS 17 COMMENT 21 PERSPECTIVE The Moral Majority Minority by Gory W. Duncan 23 SHOWBIZ by Robert Dean 26 OSCAR NOMINATIONS 29 MOVIES "Kagemusha" Reviewed by Wayne Hoefgen 35 IT'SONLY ROCK & ROLL by Christopher Hart INTERVIEW !3elinda West by Rob Clerk FICTION: WHAT'S NEXT? by Christopher Hart FICTION: WHY DO YOU THINK THEY CALL IT HIGH? by Tyson 59 HOT TEA 66 PHOTO ESSAY Kent Collier by AI Macareno 75 HIGHLIGHT The Montrose Patrol 77 MARDI GRAS Parade Schedule and New Orleans Mop 79 STARSCOPE Jupiter & Saturn Come Together 83 SPORTS 86 CALENDAR 89 CLASSIFIED 95 THE GUIDE ON OUR COVER: .••• Forth Worth's Kent Collier Photo by AI Mocoreno TWT (This Week in Texas) is published weekly by Montrose Ventures. Incorporated, at 3223 Smith Street. Suite 103. Houston, Texas 77006; phone: (713) 527-9111. Opinions expressed by columnists are not necessarily those of TWT orof its staff. Publication of the name or photograph of any person or organization in articles or advertising in TWT is not to be construed as any indication o:f the sexual orientation of said person or organization.