2. Neolithic Monanny, County Monaghan Fintan Walsh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A'railway Or Railways, Tr'araroad Or Trainroads, to Be Called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the Town of Dundalk in the Count

2411 a'railway or railways, tr'araroad or trainroads, to be den and Corrick iti the parish of Kilsherdncy in the* called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the town barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Killnacreena, Cor- of Dundalk in the county .of.Loiith to the town of nacarrew, Drumnaskey, Mullaghboy and Largy in Cavan, in the county of Cavan, and proper works, the parish of Ashfield in the barony of Tullygarvy piers, bridges; tunnels,, stations, wharfs and other aforesaid, Tullawella, Cornabest, Cornacarrew,, conveniences for the passage of coaches, waggons, Drumrane and Drumgallon in the parish of Drung and other, carriages properly adapted thereto, said in the barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Glynchgny railway or railways, tramway or tramways, com- or Carragh, Drumlane, Lisclone, Lisleagh, Lisha- mencing at or near the quay of Dundalk, in the thew, Curfyhone; Raskil and Drumneragh in the parish and town of Dundalk, and terminating at or parish of Laragh and barony of Tullygarvy afore- near the town of Cavan, in the county of Cavan, said, Cloneroy in the parish of Ballyhays in the ba- passing through and into the following townlands, rony of Upper Loughtee, Pottle Drumranghra, parishes, places, T and counties, viz. the town and Shankil, Killagawy, Billis, Strgillagh, Drumcarne,.- townlands of Dundalk, Farrendreg, and Newtoun Killynebba, Armaskerry, Drumalee, Killymooney Balregan, -in the parish of Gastletoun, and barony and Kynypottle in the parishes of Annagilliff and of Upper Dundalk, Lisnawillyin the parish of Dun- Armagh, barony of -

Portfolio of Glaslough

An oasis of calm, where the hse is king GLASLOUGH CO MONAGHAN IRELAND INfORMAtION Q pORtfOLIO xxx ENtENtE fLORAL/E EUROpE 2017 CONtENtS foreword ...........................................................1 Beautiful Glaslough .......................................2 planning & Development ...........................3 Natural Environment ...................................5 Built Environment ..........................................7 Landscape ........................................................9 Green Spaces ..............................................10 planting ...........................................................13 Environmental Education ........................15 Effort & Involvement .................................17 tourism & Leisure .....................................18 Community ....................................................21 The Boathouse at Castle Leslie Estate. fOREwORD elcome to beautiful Glaslough, t is a very special privilege to welcome an oasis of calm tucked away the International Jury of Entente Florale Wbetween counties Monaghan, Ito Co. Monaghan to adjudicate Armagh and Tyrone. We were both thrilled Glaslough as one o@f Ireland’s and honoured to be nominated to representatives in this year’s competition. represent Ireland in this year’s Entente Co. Monaghan may not be one of the Florale competition. We hope to do better known tourist destinations of Ireland justice, and that you enjoy the best Ireland, but we are confident that after of scenery and hospitality during your stay spending a day -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

File Number Monaghan County Council

DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/60 Tiarnan Hand & Rebecca P 11/02/2019 permission for a single storey house, waste water Kenny treatment plant, a new site entrance and associated site works Drumass Inniskeen Co Monaghan 19/61 Norman Francey P 12/02/2019 permission to construct a new free range poultry unit, new litter store, roads underpass, hardened area, vertical meal bins, underground washings, tanks and all ancillary site works Corkish Td Newbliss Co Monaghan 19/62 Damien & Celina Babington P 12/02/2019 permission for a dwelling house, waste water treatment unit, and percolation area, & new entrance onto public road and all associated site works Drumcarrow Carrickmacross Co Monaghan 19/63 Paul & Emma Murphy P 12/02/2019 permission to erect a two storey extension to rear of existing dwelling and all associated site works. Raferagh Shercock Co Monaghan DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. -

The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Monaghan County Council

Ceantar Bardasach Carraig Mhachaire Rois – Baile na Lorgan, Comhairle Contae Mhunieacháin The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Monaghan County Council Minutes of proceedings of AGM of The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Municipal District held in Carrickmacross Civic Offices, Riverside Road, Carrickmacross, on Friday 27th June 2014 @ 10.00 am. Present: Cllrs. Aidan Campbell, Jackie Crowe, Noel Keelan, Padraig McNally, PJ O’Hanlon, and Matt Carthy MEP Also in attendance:- Eugene Cummins, Chief Executive Monaghan County Council, Adge King, Director of Services, Cathal Flynn, Coordinator, Frances Matthews, Alan Hall, John Lennon, Joe Durnin, Mickey Duffy, Amanda Murray, Teresa McGuirk, Mary Marron, Stephanie McEneaney, Philomena Carroll Press – Veronica Corr, Northern Standard, Martin Shannon, Anglo Celt and Kieran Ward, Northern Sound Radio and Pat Byrne, photographer. Apologies - none Election of Cathaoirleach Cathal Flynn, Coordinator took the chair and welcomed all stating the AGM, represented a significant milestone in the history of local government for Carrickmacross and Castleblayney. Cllr Keelan welcomed coordinator and staff and wished well in their new roles. Cllr Keelan proposed Cllr Jackie Crowe for the position of Cathaoirleach. This was seconded by Cllr Aidan Campbell. The coordinator enquired if there were any further nominations. As no further nominations were received Mr Flynn declared Cllr Crowe duly elected as Cathaoirleach. Cllr Crowe then took the chair for the remainder of the meeting. Cllr Crowe thanked his proposer and seconder stating that he was deeply honoured and humbled to become the first chair of the new Municipal District of Carrickmacross - Castleblayney. Cllr Crowe gave his commitment to work along with coordinator, staff and elected members to ensure the Municipal District can work for the benefit of the people. -

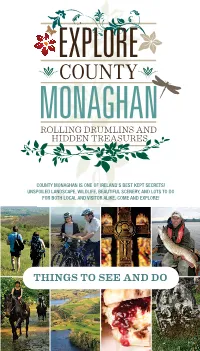

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

VA90.1.017 – Helen Drumm T.A Sound Quality

Appeal No. VA90/1/017 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHT LUACHÁLA, 1988 VALUATION ACT, 1988 Helen Drum t/a Sound Quality APPELLANT and Commissioner of Valuation RESPONDENT RE: Shop at Lot No. 12b Townland of Rooskey (Dublin Street), Urban District of Monaghan, Co. Monaghan Quantum - Passing rent, location adjacent to S.C. B E F O R E Henry Abbott Barrister Chairman Brian O'Farrell Valuer Veronica Gates Barrister JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 22ND DAY OF JANUARY, 1991 By notice of appeal dated the 30th of April, 1990, the appellant appealed against the determination of the Commissioner of Valuation in fixing a rateable valuation of £26.00 on the above described hereditament. The grounds of appeal as set out in the Notice of appeal are "I have the wholly confined use of a small on-street shop premises. I operate a record/tape retail outlet and am two years in business. This is my first venture into business life having been three years umemployed. There is stiff competition here and I am finding it altogether very difficult to manage. This is penal in the 2 extreme and may leave me no choice but to join the many other young people who have already found themselves unable to succeed in todays high cost business world." DESCRIPTION OF PROPERTY: The premises consist of a lock-up 'record shop' with frontage to Dublin Street, Monaghan. It is situated approximately 200 ft from The Diamond. It is held on a three year lease from March 1988. There is a shop floor area of 237 sq.ft. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS 576 DOCUMENT NO. W.S. Witness Eugene Sherry, Clontibret, Castleblayney, Co. Monaghan. Identity. Member Of Clontibret (Co. Monaghan) Company Irish Volunteers, 1916 ; Captain same Company, 1919 Subject. The (a) Irish Volunteers, Co. Monaghan, 1914 ; (b) Military activities, Co. Monaghan, 1920-1921. Conditions, If Any, Stipulated by Witness. S.1831. File No Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Eugene Sherry, Clontibret, Castleblaney, Co. Monaghan. I joined the Volunteers early probably before 1916. This organisation was of little value. We took part in drills and training. A man named Cusack came from Monaghan town and put us through training exercises. Easter Week 1916 passed without any local incident taking. place. The start of re-organising the Volunteers after 1916 took place in our area about 1919. I then joined the Clontibret Company. I was the first Company O/C and remained in charge of the Company until 1922. About thirty men joined at the start of the Company and the membership gradually increased up to the Truce when we had 63 or 64 on the rolls. Clontibret Company was part of the Monaghan town Battalion from 1919 onwards. In 1919 we had little arms some shotguns, a few pin fire revolvers-of antiquated make and some ammunition for the revolvers. We had to rely on what we had or on what we got by raiding forearms. I purchased a few revolvers myself. This was all the purchase of arms as far as I know in the Company area. In 1920 at the general raid for arms we made a canvass amongst all friendly houses within the Company area and we handed over a number of shotguns. -

Ballybay Moffetts : a Brief History of the Crievagh House, Ballybay, County

I !l ' I BALLYBAY MOFFETTS .^-j-i'j I ].....(; ! ! I I .U,.J- diss wU U !)()( I. .Hg PHKSK.NTKl) BY (Y^:\^C^^CP^ BALLYBAY MOFFETTS A Brief History of the Cricvagh House Ballybay County Monaghan, Ireland, Branch of the Moffctt Family BY GEORGE AND ADAM MOFFETT ASSISTED nV DTHEKS OF THE NAME The data ot the families living in England and Ireland was furnished by Rev. Joseph Moffctt and Frank J. Moffctt, Esq. 1908 as-;/ EXPLANATION. The number following the name in this work is the number of the gener- ation to which the person belongs, which can be traced by referring to the outline pages at the beginning—the first one of the name that we have any record of being taken as generation No. 1 . Blank pages are for any data that you may wish to record in regard to the names on opposite page. At the back are pages for records of births, marriages and deaths, and we ask that you keep a record of your family here as complete as possible as it may be of assistance to some in the future, who may wish to bring this history up to a fu- ture date. Copies of this book can be had by addressing Dr. Geo. Moffett, 30't' • i ., Kui]ju.t Moffett, CllwiyVSlte,^^iiciiyvaie Kdub. ^ammacw Dldi City , Mo., or Dr. A. Cj ^ fjl PREFACE. In preparing this brief history of the Ballybay, Ireland, branch of the Moffett family, we have endeavored to make it as complete as pos- that sible with the facilities we had at hand. -

Peter Sweetman & Associates Rossport South Ballina

PETER SWEETMAN & ASSOCIATES ROSSPORT SOUTH ., a* .-> I . BALLINA " COUNTY MAYO [email protected], ~ :I "< ,d ', !G : ' Environmental Protection Agency Johnstown Castle .. Wexford ,, 2014-05-13 i ' : 1 Submission RE; I P0408- Carrickboy Farms, Ballyglassi'n, Edgeworthstown, Mr Dona1 Brady 02 Co. Longford. P0422- Silver Hill.Foods Hillcrest, Emyvale, County Monaghan. 03 I P0837- F. OHarte Poultry Creevaghy, Clones, County Monaghan. 02 Limited f ,I I. P0857- JPH Enterprises Quiglough, Ballinode, County Monaghan. 02 Limited , For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. ,I I, P0862- Mr James McGuirk Tetoppa, Dunraymond, County Monaghan. 02 P0923- Mi Paraig Kiely Carrowhauny, Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo. 01 I P0929- Mr Pat Kenny Coolanoran, Newcastle West, Co. Limerick. 01 P0930- Mr Francis McCluskey Drumully, Smithboro, Co. Monaghan. 01 "I P0937- ? Mr Damien Treanor Killnagullan, Emyvale, County Monaghan. 01 PO95 1- Mr Dermot Crinion Dowth, Slane, County Meath. 01 II 1 EPA Export 01-09-2015:23:34:12 .. '0956- vir John McCabe Brandrum, Monaghan, County Monaghan. 11 rankerstown Pig & '0965- :arm Enterprises rankerstown, Bansha, Tipperary, County Tipperary. I1 Limited PO97 1- Martin and Mhairi Barnagurry, Kiltimagh, County Mayo. I1 Iempsey ~ P0972- I.M.K. Pigs Limited Lacklom & Ballintra, Inniskeen, County Monaghan. 31 P0975- Zlondrisse Pig Farm Joristown Upper, Killucan, County Westmeath. D1 Limited P0976- Senark Farm Limited Aghnaglough, Stranooden, County Monaghan. 02 P0979- Thomas & Trevor Ballyharrahan, Ring, CO Waterford. 0 1. Galvin , PO98 1- DIN0 Trading Limited Levalley, Ballinrobe, COMayo. 01 /I P0982- I Mr Don French Cloonee, Durrus, County Cork. 01 P0984- Clondrisse Pig Farm Bracklyn, Delvin, County Westmeath. 01 Limited ~ ,. -

Prospecting Licence Area No. 2194, County Monaghan O.S. 6

Prospecting Licence Area No. 2194, County Monaghan O.S. 6” Monaghan 10 and 14 Townlands in Cremorne Barony: Aghnameal, Annahuby, Annaseeragh, Ballygreany, Bryanlitter, Carrickaderry, Clerran, Corcaskea, Corlagan North, Cornabrandy, Doosky, Downs, Dromore (E.D. Clontibret), Drumbeo, Drumnart, Ennis, Feddans, Fintully, Gallagh, Glasdrumman West, Glennyhorn, Greenmount, Kilcrow, Lisaginny, Lisglassan, Listinny, Moy Etra, Moy Otra, Mullagarry, Mullans, Shanemullagh, Shanmullagh, Tirmacmoe, Tullybuck Townlands in Monaghan Barony: Aghnagap, Aghnaglogh (E.D. Rackwallace), Ardaghy, Ballycronog, Braddocks, Castleshane Demesne, Cordevlis, Corfad, Corlust, Cormurphy, Corraskealy, Corrawillin, Corrinshigo (E.D. Tullycorbet), Corvally (E.D. Tullycorbet), Creeve, Edenbrone (E.D. Castleshane ), Lattigar, Legnacreeve, Lismenan, Listraheagny, Rackwallace Area: 31.75 square kilometres 271000 272000 273000 274000 275000 276000 277000 278000 279000 KNOCKACUNNIER SKINNAGIN KILLEEF 0 TEMPLETATE LEITRIM 0 0 TAMLAT 0 0 TULLYGONY 0 6 6 3 TULLYNANURE LAPPAN 3 3 3 TULLYLISHTUCKMILLTATE KILLYNEILL GROVES LOWER CARN CAVANCREEVY KNOCKBOY KILDOAGH Ü 0 GARRAN ITRA 0 0 0 0 ANNACRAMPH 0 LISCONDUFF 5 GOLREE 5 3 MULLAGHMORE 3 3 GROVES UPPER DRUMNEILL 3 FEDOO DERRY KILLYMONAGHAN KILLYCARNAN GARRAN OTRA or GIBRALTAR CULDALOO 0 ALKILL 0 0 COOLMAIN 0 0 0 4 4 3 CORNAHOE LOWER 3 CLONLONAN CARROWKEEL DRUMMUCK 3 3 FEEBANE AGHALAVERTY DROMORE TIRAVRAY KINARDDRUMNAHUNSHIN LISDRUMDOAGH KINGORRY TULLYCUMASKY 0 DRUMGOLAT 0 0 TIRFINNOG 0 0 KILLYMARLY 0 AGHABRICK 3 CORDEVLIS 3 GREENMOUNT -

Monaghan Brochure

www.orphismedesign.com rphisme Y O B design W www.discoverireland.ie/northwest T (071) 9161201 (071) Temple Street, Sligo Street, Temple Failte Ireland North West North Ireland Failte ound) R ear Y pen O ( T S E W ˆ ORTH N RELAND I DawsonMonument, Rockcorry FAILTE W www.monaghantourism.com T (047) 81122 (047) Clones Road, Monaghan Road, Clones Monaghan Leisure Complex Leisure Monaghan (Seasonal: Jun-Sept) (Seasonal: E E C I Off T S OURI T MONAGHAN Tourist Offices Tourist ˇ Hilton Park, Scotshouse, Clones Scotshouse, Park, Hilton information welcome GUIDE do to things MOURNE CLAY SHENANDOAH STABLES SHOOTING GROUND Lough Egish, Castleblayney Loughmourne, Castleblayney T (042) 9745293 T (042) 9745953 E [email protected] T (087) 9969946 W www.shenandoah-stables.info E [email protected] W www.clayshooting.ie MULLAGHAMORE EqUESTRIAN CENTRE PLANET KIDZ Mullaghmore, Tydavnet Unit B1, Monaghan Business T (047) 89645 Park, Clones Road, Monaghan T (087) 6600629 T (047) 75830 T (087) 9973435 CARRICKMACROss EqUESTRIAN CENTRE THE COOKERY SCHOOL Carrickmacross AT CASTLE LESLIE T (042) 9661017 Glaslough T (047) 88100 E [email protected] Attractions W www.castleleslie.com PATRICK KAVANAGH CENTRE Equestrian Inniskeen T (042) 9378560 CLONCAW E [email protected] EqUESTRIAN CENTRE W www.patrickkavanaghcountry.com Sliabh Beagh things to do… Glaslough ˆ T (047) 88882 MONAGHAN E [email protected] COUNTY MUSEUM W www.cloncaw.com 1-2 Hill Street, Monaghan T (047) 82928 CASTLE LESLIE E [email protected] Introduction Activity EqUESTRIAN CENTRE Glaslough SAM MORE OpEN FARM Monaghan visitors are Water sports include water- MONAGHAN SWImmING BLAYNEY BOWLS & T (047) 88100 Threemilehouse immediately struck by the skiing, wake boarding, kayaking POOL & LEISURE COmpLEX PARTY ZONE E [email protected] (near Monaghan Town) Clones Road, Monaghan Monaghan Road, Castleblayney unexpected charm of this and of course, Monaghan is W www.castleleslie.com T (086) 2322601 friendly county.