2014 Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derbyshire Attractions

Attractions in Derbyshire Below is a modified copy of the index to the two folders full of 100 leaflets of attractions in Derbyshire normally found in the cottages. I have also added the web site details as the folders with the leaflets in have been removed to minimise infection risks. Unless stated, no pre-booking is required. 1) Tissington and High Peak trail – 3 minutes away at nearest point https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/visiting/places-to-visit/trails/tissington-trail 2) Lathkill Dale 10 minutes away – a popular walk down to a river from nearby Monyash https://www.cressbrook.co.uk/features/lathkill.php 3) Longnor 10 minutes away – a village to the north along scenic roads. 4) Tissington Estate Village 15 minutes away – a must, a medieaval village to wander around 5) Winster Market House, 17 minutes away (National Trust and closed for time-being) 6) Ilam Park 19 minutes away (National Trust - open to visitors at any time) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/ilam-park-dovedale-and-the-white-peak 7) Haddon Hall 19 minutes away https://www.haddonhall.co.uk/ 8) Peak Rail 20 minutes away https://www.peakrail.co.uk/ 9) Magpie Mine 20 minutes away https://pdmhs.co.uk/magpie-mine-peak-district/ 10) Bakewell Church 21 minutes 11) Bakewell Museum 21 minutes open tuesday, wednesday Thursday, saturday; https://www.oldhousemuseum.org.uk/ 12) Thornbridge brewery Shop 23 minutes https://thornbridgebrewery.co.uk/ 13) Thornbridge Hall – open 7 days a week https://www.thornbridgehall.co.uk 14) Cauldwells Mill – Rowsley 23 minutes upper floors of mill -

A Year in the Life of the Village During the Pandemic

1 Header April 2021 Body of text A YEAR IN THE LIFE OF THE VILLAGE DURING THE PANDEMIC As this edition of the News is published just over a year after the first national lockdown, I thought it would be good to remind ourselves of all the amazing support and lockdown activities that have taken place. I refer to some individuals by name but please forgive the fact that I am unable to name check everyone. As we went into the first lockdown the Parish Council provided funds for some mobile phones and the shop swung into action setting up prescription and food delivery/emergency help Whatsapp groups as well as establishing a team of street wardens to keep a check on any residents who may not have had access to social media. Both prescription delivery from Eyam and street wardens are still in operation. Peter O’Brien, our District Councillor, kept us posted on information from Derbyshire County Council and, most importantly for many of us, details of bin collections! Even during these difficult times stalwart volunteers, along with managers Sarah and Andrew kept the shop open and it even went online. The virtual shop idea which evolved from that is developing further and will hopefully mean an expanded range of goods available online sometime over the summer. Our local Spar (White’s)introduced a delivery service which along with our shop provided a lifeline to those who were shielding and found it impossible to get a delivery from one of the large supermarkets. It was hard to go hungry when Terry from the Sir William decided to start fish and chip Friday with delivery by Diane and Bob Wilson and John and Pauline Bowman. -

UNDER the EDGE INCORPORATING the PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW No

UNDER THE EDGE INCORPORATING THE PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW www.undertheedge.net No. 268 May 2021 ISSN 1466-8211 Stars in His Eyes The winner of the final category of the Virtual Photographic (IpheionCompetition uniflorum) (Full Bloom) with a third of all votes is ten year old Alfie Holdsworth Salter. His photo is of a Spring Starflower or Springstar , part of the onion and amyrillis family. The flowers are honey scented, which is no doubt what attracted the ant. Alfie is a keen photographer with his own Olympus DSLR camera, and this scene caught his eye under a large yew tree at the bottom of Church Lane. His creativity is not limited just to photography: Alfie loves cats and in Year 5 he and a friend made a comic called Cat Man! A total of 39 people took part in our photographic competition this year and we hope you had fun and found it an interesting challenge. We have all had to adapt our ways of doing things over the last year and transferring this competition to an online format, though different, has been a great success. Now that we are beginning to open up and get back to our normal lives, maybe this is the blueprint for the future of the competition? 39 people submitted a total of 124 photographs across the four categories, with nearly 100 taking part in voting for their favourite entry. Everyone who entered will be sent a feedback form: please fill it in withJane any Littlefieldsuggestions for the future. -

Derbyshire. [Kelly's

B DERBYSHIRE. [KELLY'S • LORD LIEUTENANT AND CUSTOS ROTULORUM. HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF DEVOXSHIRE K.G., P.C., D.C.L" LL.D., F.R.S. Chatsworth, Chesterfield; & 78 Piccadilly, London W. CHAIRMAN OF QUARTER SESSIONS.-JOH~ EDWARD BARKER Esq. Q.C. Brooklands, Buxton. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN.-ROBERT SACHEVERELL WILMOT SITWELL Esq. Horsley hall, Derby. Marked thus • Bre Deputy-Lieutenants. Alleyne Sir John Gay Newton hart. Chevin house, Belper Carrington Arthur esq. 'Warney Lea, Darley Dale. Allsopp Tbe Hon. George Higginson M.A., M.P. Foston Matlock Bath h::d, Derby Carver Thomas esq. The Hollins, Marple Andrew Ely esq. Albert house, Ashton-under-Lyne *Cave-Brown-Cave Sir Mylles bart. Stretton hall, AnS!)ll Henry esq. Bonehill lodge, near Tamworth Stn'tton-en-Ie-Fields, Ashby-de-Ia-Zouch Arkwright Francis esq. },{arton, Wellington, New Zealand Cavendish Col. .Tames Charles, Darley house, Darley Arkwright Frederic Oharles esq. Willersley, Cromford, Abbey, Derby; & 3 Belgrave place, London SW 'Matlock l3ath Chandos-Poie Reginald Walkelyne esq. Radburne haU, AsM'm Robt. How esq. Loosehill hall, Castleton, Sheffield Derby Badnall William Beaumont esq. Thorpe, Ashborne Chandlls-Pole-Gell Henry esq. Hopton hall, Wirksworth *Ragshawe Francis Westby esq. M.A. The Oaks, Norton, Christie Richard Copley esq. M.A. Ribsden, Windlesham, Sheffield Bagshot, Surrey *Bagshawe His Honor Judge William Henry Gunning Q.C. ClayAlfreJ esq. Darley hall, near Matlock 249 Cromwell road, London SW Cla.y Charles John esq. B.A. Stapenhill, Burton-on-Trent Bailey John esq. Temple house, Derby *Clowes Samuel William esq. B.A. Norbury, Ashborne Ball JoLn esq. Dodson house, Ilkeston *Coke Col. -

Under the Edge Incorporating the Parish Magazine Great Longstone, Little Longstone, Rowland, Hassop, Monsal Head, Wardlow

UNDER THE EDGE INCORPORATING THE PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW No. 173 June 2013 60P ISSN 1466-8211 Sites for Multi Use Sports Area As you will be aware the Parish Council are looking into the village facility of a Multi Use Sports Area, to enable more sports to be played beyond the limitations of the current tennis, football and cricket. The Parish Council are approaching landowners in the immediate vicinity of the village with regards to the possibility of any fields becoming available for such a use. SarahPlease Stokescontact Clerk me if toyou Great feel Longstoneyou may have Parish a field. Council, Any conversationsLongstone Byre, or Little correspondence Longstone, Bakewell,on this subject Derbyshire, will be DE45kept in 1NN. the Tel:strictest 01629 confidence 640851 Email:and will [email protected] not be permitted to go into the public domain without any written consent. Photo: The Farmers Guardian Article. Farming Notes June 2013 The Farmers Guardian is a nationally circulated farming newspaper, read especially by livestock farmers. Recently I had a telephone call from them asking if they could publish a piece about our farm in their Farm Focus section. I said that I didn’t think that our farm was anything special but they thought that their readers would be interested as we had a mixture of income streams: milk production and retailing, sale of pedigree dairy cattle, a pedigree Charolais herd, a bull beef unit go ahead with the article and a reporter and photographer came to take details and lots of photographs of the stock, the milkand the bottles Higher and Lever of Dan, Stewardship Tom and myself. -

All Approved Premises

All Approved Premises Local Authority Name District Name and Telephone Number Name Address Telephone BARKING AND DAGENHAM BARKING AND DAGENHAM 0208 227 3666 EASTBURY MANOR HOUSE EASTBURY SQUARE, BARKING, 1G11 9SN 0208 227 3666 THE CITY PAVILION COLLIER ROW ROAD, COLLIER ROW, ROMFORD, RM5 2BH 020 8924 4000 WOODLANDS WOODLAND HOUSE, RAINHAM ROAD NORTH, DAGENHAM 0208 270 4744 ESSEX, RM10 7ER BARNET BARNET 020 8346 7812 AVENUE HOUSE 17 EAST END ROAD, FINCHLEY, N3 3QP 020 8346 7812 CAVENDISH BANQUETING SUITE THE HYDE, EDGWARE ROAD, COLINDALE, NW9 5AE 0208 205 5012 CLAYTON CROWN HOTEL 142-152 CRICKLEWOOD BROADWAY, CRICKLEWOOD 020 8452 4175 LONDON, NW2 3ED FINCHLEY GOLF CLUB NETHER COURT, FRITH LANE, MILL HILL, NW7 1PU 020 8346 5086 HENDON HALL HOTEL ASHLEY LANE, HENDON, NW4 1HF 0208 203 3341 HENDON TOWN HALL THE BURROUGHS, HENDON, NW4 4BG 020 83592000 PALM HOTEL 64-76 HENDON WAY, LONDON, NW2 2NL 020 8455 5220 THE ADAM AND EVE THE RIDGEWAY, MILL HILL, LONDON, NW7 1RL 020 8959 1553 THE HAVEN BISTRO AND BAR 1363 HIGH ROAD, WHETSTONE, N20 9LN 020 8445 7419 THE MILL HILL COUNTRY CLUB BURTONHOLE LANE, NW7 1AS 02085889651 THE QUADRANGLE MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY, HENDON CAMPUS, HENDON 020 8359 2000 NW4 4BT BARNSLEY BARNSLEY 01226 309955 ARDSLEY HOUSE HOTEL DONCASTER ROAD, ARDSLEY, BARNSLEY, S71 5EH 01226 309955 BARNSLEY FOOTBALL CLUB GROVE STREET, BARNSLEY, S71 1ET 01226 211 555 BOCCELLI`S 81 GRANGE LANE, BARNSLEY, S71 5QF 01226 891297 BURNTWOOD COURT HOTEL COMMON ROAD, BRIERLEY, BARNSLEY, S72 9ET 01226 711123 CANNON HALL MUSEUM BARKHOUSE LANE, CAWTHORNE, -

Forward Works Programme for Highways Maintenance Asset

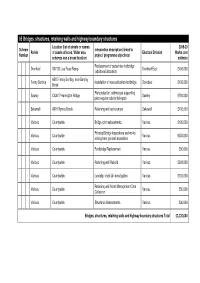

05 Bridges, structures, retaining walls and highway boundary structures Location (list of streets or names 2019-20 Scheme Intervention description (linked to Parish of assets affected. Wider area Electoral Division Works cost Number project/ programme objectives) schemes use a broad location) estimate Replacement of pedestrian footbridge Dronfield V37123 Lea Road Ramp Dronfield East £400,000 (additional allocation) A515 Fenny Bentley, near Bentley Fenny Bentley Installation of new pedestrian footbridge Dovedale £100,000 Brook Pier protection, submerged supporting Sawley C43017 Harrington Bridge Sawley £700,000 piers require substantial repair Bakewell A619 Rymas Brook Retaining wall replacement Bakewell £100,000 Various Countywide Bridge joint replacements. Various £100,000 Principal Bridge Inspections and works Various Countywide Various £250,000 arising from general inspections Various Countywide Footbridge Replacement Various £90,000 Various Countywide Retaining wall Rebuild Various £300,000 Various Countywide Landslip / rock fall investigation Various £100,000 Retaining wall Asset Management Data Various Countywide Various £50,000 Collection Various Countywide Structures Assessments Various £30,000 Bridges, structures, retaining walls and highway boundary structures Total £2,220,000 05 Bridges, structures, retaining walls and highway boundary structures Location (list of streets or names 2020-21 Scheme Intervention description (linked to Parish of assets affected. Wider area Electoral Division Works cost Number project/ programme objectives) -

Mansions, Mills and Master Gardeners

Barrington Community School and Barrington Garden Club present Mansions, Mills and Master Gardeners June 1st - 9th 2018 The Peak District National Park covers 555 square miles right in the center of Britain, straddling the Pennine Mountain range, known as the “Backbone of England.” Created in 1951 it was the first National Park in the country and is remarkable not only for its natural beauty, but also because it exists in the midst of the country’s industrial heartland. We make our base for this tour in the charming town of Buxton, a Victorian spa town, in the very center of the park and famous for its annual opera festival. Buxton is also within easy striking distance of Manchester International Airport, and its central location means that we can do the whole tour from this one base, Mam Tor, Peak District with daily excursions to sites all around. We have included a fascinating array of visits that highlight the contrast between the natural beauty of the countryside and the industrial heartland that surrounds it. From the variety of gardens of the stately homes spanning several centuries, to one of the country’s foremost industrial heritage sites, the Quarry Bank Mill at Styal and the Wedgwood factory museum in the heart of the Potteries, we will explore the region in depth – “warts and all,” as they say. For many though, the highlight of this tour will be the day we spend at the home of the Dukes of Devonshire - Chatsworth House, known as the Palace of the Peaks. Chatsworth has recently become the stage for the Royal Horticultural Society’s latest flower show that, some say, rivals The Chelsea Flower Show! We’ll have a private tour of the house and we have included membership in the RHS in the tour cost, so that we can attend the member’s only day at the show. -

PEAK DISTRICT Privilege Card

PEAK DISTRICT Privilege Card Be our guest! Enjoy your stay in our cottage by treating yourself to these special privileges Simply show the Privilege Card on entry to these popular Peak District places… UNIQUE EXPERIENCES Guy Badham Photography offers a day Guy Badham Photography of photography skills training with www.guybadhamphotography.com renowned wildlife and landscape Email: [email protected] photographer Guy Badham - partner Tel: 07980 587521 photographer for the Peak District Open: Tourist Board and used extensively by Book in advance Derbyshire Wildlife Trust. Offer: Two for the price of one Live for the Hills offer bespoke trips Live for the Hills around the Peak District in comfort and www.liveforthehills.com style with your own personal driver. Email: [email protected] Whether you’re on your own, a couple Tel: 07500 844744 or in a group, experience the Peaks, its Open: people and its places and enjoy a Book in advance relaxing and memorable day out. Licensed to carry up to 6 passengers Offer: £10 off a full day tour Peak Walking Adventures offer Peak Walking Adventures personal walking guides and group www.peakwalking.com walks in the beautiful Peak District Tel: 07870 778 585 countryside Open: Offer: 20% off Personal Walking Guide Book in advance Mon to Fri (excludes bank holidays) Phil Sproson Photography offers Phil Sproson Photography wonderfully relaxed and fun www.philsprosonphotography.com photoshoots, which can take place in www.facebook.com/philsprosonphoto the comfort of your cottage or out & graphy about against the magnificent backdrop Tel: 07966 509726 of the Peak District Open: Offer: 10% off Book in advance Vintage Adventure Tours offer a Vintage Adventure Tours unique opportunity to experience the www.vintageadventuretours.co.uk Peak District in style. -

December 2009 50P ISSN 1466-8211 Wet Weather Fails to Dampen Spirit of Crispin Walkers Crispin/Thornhill Charity Walk Day - Almost £2000 Raised

UNDER THE EDGE INCORPORATING THE PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW No. 131 December 2009 50P ISSN 1466-8211 Wet weather fails to dampen spirit of Crispin walkers Crispin/Thornhill charity walk day - almost £2000 raised The skies darkened further so I decided to press on into Tideswell Dale eventually reaching Litton Mill where Tim Biddlecombe had been strategically posted to warn walkers of the dangers of choosing the high-level, 'alpine' path above this stretch on such a miserable, damp day. Sensibly, everyone opted for the easy-walking, riverside path down to Water-cum-jolly-Dale before the short climb onto the Monsal Trail, up to Monsal Head and back, via Little Longstone, to the rejuvenating liquid refreshments and pie & peas available at the Crispin. With most walkers now returned from the day's duties, even more funds were raised by way of a The charity walkers (morning clan) gather outside the Crispin This year's winners of the most moneyraffle of raiseddonated through prizes. Sponsorship The day (Saturday Oct 24th) began, Moor. As we climbed, however, the mist were Bob and Esther Stewart with a disappointingly, with grey skies, rolling thickened and visibility dropped to just remarkable £500+ total. Last year's mist and light rain falling steadily a few metres. winner, Pig Rowlinson (a pure white, over Great Longstone - hardly ideal So, I decided that I needed to hold dog-like creature who lodges at the conditions for a charity walk and back and ensure that those already pub), was unavailable for comment! the inclement weather surely had behind didn't get lost as conditions Walking times (10 miles) ranged a negative effect on the number of were deteriorating rapidly. -

Premise Classification Report

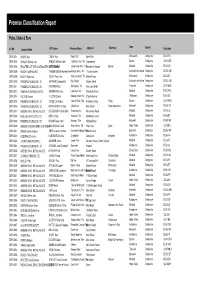

Premise Classification Report Pubs, Clubs & Bars Address2 Town County Lic No Licence Holder DPS Name Premise Name Address1 Postcode DDPL0001 DRURY Avis DRURY Avis Royal Oak North End Wirksworth Derbyshire DE4 4FG DDPL0002 ARNOLD Michael John ARNOLD Michael John Packhorse Inn, The Crowdecote Buxton Derbyshire SK17 0DB DDPL0006 TRUSTEES OF THE CHATSWORTH SHELTONSETTLEMENT Iain Devonshire Arms, TheDevonshire Square Beeley Matlock Derbyshire DE4 2NR DDPL0008 PUNCH TAVERNS PLC FRASER-SMITH Andrew PeterAshford Arms, The 1 Church Street Ashford in the Water Derbyshire DE45 1QB DDPL0009 BOOTH Peter Alan BOOTH Peter Alan Red Lion Hotel, The Market Place Wirksworth Derbyshire DE4 4ET DDPL0010 FREDERIC ROBINSON LTD MAYNARD George Blair Bulls Head Church Street Ashford in the Water Derbyshire DE45 1QB DDPL0011 FREDERIC ROBINSON LTD CROPPER Paul Anchor Inn, The Four Lane Ends Tideswell Derbyshire SK17 8RB DDPL0012 ADMIRAL TAVERNS LIMITED MAINWARING Jane Laburnum Inn 2 Hackney Road Matlock Derbyshire DE4 2PW DDPL0014 FULTON Graeme FULTON Graeme Bowling Green Inn 2 North Avenue Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 1EZ DDPL0015 FREDERIC ROBINSON LTD DOYLE Christopher Duke of York, The Ashbourne Road Flagg Buxton Derbyshire SK17 9QG DDPL0016 FREDERIC ROBINSON LTD ROWLINSON Paul Roy Crispin Inn Main Street Great Longstone Bakewell Derbyshire DE45 1TZ DDPL0017 GREENE KING RETAILING LTD. STEVENSON Patrick Mark Thorntree Inn 48 Jackson Road Matlock Derbyshire DE4 3JQ DDPL0018 RED LION (MATLOCK) LTD. MEWS Philip Red Lion, The 65 Matlock Green Matlock Derbyshire DE4 3BT -

Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History

J^o. VOL. XX. 1898. OURNAL OF THE .Irchjeologicjil AND Natural History OCI£TY. FBZNTISD POB. THE SOCIETY BY BEMB.OSE & SONS, IiZMITED, 23, OLD BAILEY, LONDON; AND DERBY. ^ JOURNAL OF THE 2)ei*b^8bice Hrcba^olOGical AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY EMIT FT) RV RE\^ CHARLES KERRY Keelor of Upper Stoiitiov Be./s. VOL. XX JANUARY 1898 Printed jor the Societv bv BEMROSE .V SONS LTD. 23' OLD B\n.EY LONDON AND DERBY CONTENTS. PAGE List of Officeks v Rules ^''i List of MEMiisiKs " Secretary's Report xvii Balance Sheet xxii Agreement of the Freeholders in Eyam to ihe Award for DIVIDING Eyam Pasture, i2th November, 1702. Contributed by Chas. E. B. Bowles . - - i A FEW BRIEF notes OX SOME RECTORS AND ViCAKS OF HeANOK, CO. Derby. 12 By the Rev. R. J. Burton Will of Elizabeth FitzHerbert, Widow of Ralph Fiiz- Herbert, Esq., of Norbury, Derbyshire, Dated 20th October, 1490. CONIKIBUTED BY ReV. REGINALD H. C. FITZHERBERT - 32 The Ancient Painted Window, Hault Hucknall Church. By the Rev. C. Kerry 40 The Court Rolls of the Manor of Holmesfield, co. Derby, with no IKS BY THE EDITOR 52 ILLUSTRATIONS. Seven Plates of the Painted Window ai Hault Hucknall Church. : : LIST OF OFFICERS THE DUKE OF RUTLAND, K. G. of York. The Most Reverend The Lord Archbishop W. M. Jervis. Duke of Norfolk, K.G., E.M. Hon. Frederick Strutt. Duke of Devonshire, K.G. Hon. Right Rev. Bishop Abraham. Duke of Portland. Right Rev. The Bishop of Lord Scarsdale. Derby. Lord Vernon. Wilmot, Bart., V.C, Lord Waterpark.