Target Litigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legendary Corporate Defender Sheila Birnbaum ’65 Is Uniquely Suited to Her Newest Assignment: Own Special Master of the 9/11 Fund

tort à la mode NYU Law faculty are pushing the modernization of one of our oldest legal systems. wikileaks, unplugged Nine experts in law and journalism debate unauthorized disclosures, civil rights, and national security. the next president of egypt? Mohamed ElBaradei (LL.M. ’71, J.S.D. ’74, LL.D. ’04) THE MAGAZINE OF THE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW | 2011 leads in the polls. A CLASS OF HER Legendary corporate defender Sheila Birnbaum ’65 is uniquely suited to her newest assignment: OWN special master of the 9/11 fund. Saturday, April 27–28, 2012 & NYU School of Law REUNION Friday Please visit law.nyu.edu/alumni/reunion2012 for more information. 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 19 97 2002 2007 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 A Note from the Dean Twenty years ago, the Law School magazine made its debut with a cover celebrating 100 years of women at NYU Law. So I am particularly proud to have Sheila Birnbaum ’65 profiled in this issue’s cover feature, on page 28. Her story of defying society’s narrow expectations for women in the ’60s to become one of the most accomplished and respected corporate lawyers in the nation is inspiring. Just days before we photographed her, Sheila was appointed special master of the $2.8 billion September 11th Victim Compensation Fund. It is a testament to her prodi- over two issues: whether counsel on the Pentagon gious talents and expertise that federal health and safety stan- Papers case, a physicist, and a the Justice Department has dards block private litigation, lawyer involved in the investi- entrusted Sheila to recom- and just how large punitive gation of the leak that exposed pense the rescue workers and damage awards should be. -

Impact Report We Stand for Wildlife® SAVING WILDLIFE MISSION

2020 Impact Report We Stand for Wildlife® SAVING WILDLIFE MISSION WCS saves wildlife and wild places worldwide through science, conservation action, education, and inspiring people to value nature. R P VISION E R V O O T WCS envisions a world where wildlife E C SAVING C thrives in healthy lands and seas, valued by S I WILDLIFE T societies that embrace and benefit from the D diversity and integrity of life on Earth. & WILD PLACES INSPIRE DISCOVER We use science to inform our strategy and measure the impact of our work. PROTECT We protect the most important natural strongholds on land and at sea, and reduce key threats to wildlife and wild places. INSPIRE We connect people to nature through our world- class zoos, the New York Aquarium, and our education and outreach programs. 2 WCS IMPACT REPORT 2020 “It has taken nature millions of years to produce the beautiful and CONTENTS wonderful varieties of animals which we are so rapidly exterminating… Let us hope this destruction can 03 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT/CEO AND CHAIR OF THE BOARD be checked by the spread of an 04 TIMELINE: 125 YEARS OF SAVING WILDLIFE AND WILD PLACES intelligent love of nature...” 11 CONSERVATION SCIENCE AND SOLUTIONS —WCS 1897 Annual Report 12 How Can We Prevent the Next Pandemic? 16 One World, One Health 18 Nature-Based Climate Solutions LETTER FROM THE 22 What Makes a Coral Reef Resilient? PRESIDENT/CEO AND CHAIR OF THE BOARD 25 SAVING WILDLIFE 26 Bringing Elephants Back from the Brink This year marks the 125th anniversary of the founding of expertise in wildlife health and wildlife trafficking, 28 Charting the Path for Big Cat Recovery the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1895. -

My 64 Years at NYU — 1952 to 2016

My 64 Years at NYU — 1952 to 2016 Martin Lipton On October 5, 2015, I stepped down as chairman of the Board of Trustees of New York University. My tenure as Chairman began in 1998, but my relationship with NYU goes back much further—to 1952. Over the years, I have been continuously involved with NYU and the NYU community as a student, teacher, active alumnus, trustee, Chairman, and now as Chairman Emeritus. I have participated in the evolution of what was a regional commuter university into what today is recognized both as one of the great national academic institutions and as the leading global university. In return, NYU has played a significant role in my own career. The NYU School of Law introduced me not only to the law itself, but to the three partners with whom I founded the law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, which has become one of the most preeminent law firms in the world. Put simply, my life has been intertwined with NYU for 64 years. This is the story of that very special relationship. My Years in Law School In 1952, I graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania with a business degree and decided to go to law school. I applied to, and was accepted by, the NYU School of Law. My father had wanted me to go to the Wharton School and become an investment banker. But when I graduated in 1952, investment banking wasn’t the career opportunity it is today. I thought what I would really like to do is be a lawyer. -

The Global Orchestra

2006 ANNUAL REPort Avery Fisher Hall 10 Lincoln Center Plaza New York, NY 10023-6970 Telephone: (212) 875-5900 Fax: (212) 875-5717 nyphil.org The Global Orchestra NEW YORK, NY, SINCE 1842 ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA 1974 | AKRON, OH 1947 1927 1918 1917 | ALBANY, NY 1964 1920 1917 1916 1912 | ALBUQUERQUE, NM 1955 | ALLENTOWN, PA 1921 | AMES, IA 1989 1979 1976 1972 1969 1955 | AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS 2005 2000 1995 1988 1985 1968 | ANCHORAGE, AK 1961 | ANN ARBOR, MI 2005 1972 1969 1967 1963 1955 1940 1939 1916 | APPLETON, WI 1921 | ARDMORE, OK 1916 | ASHEVILLE, NC 1973 | ASHTABULA, OH 1920 | ASUNCION, PARAGUAY 1958 | ATHENS, GREECE 1995 1988 1959 1955 | ATLANTA, GA 2003 1970 1960 1954 1949 1947 | ATLANTIC CITY, NJ 1960 | AUBURN, NY 1916 1913 | AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND 1974 | AURORA, NY 1916 1915 | AUSTIN, TX 1916 | BAALBECK, LEBANON 1959 | BADEN-BADEN, 2006 GERMANY 2005 2002 | BALTIMORE, MD 1963 1962 1961 1947 1940 1939 1929 1928 1927 1926 1925 1924 1916 1915 1914 1913 1912 1911 | BANGKOK, THAILAND 1989 1984 | BARCELONA, SPAIN ANNUAL 2001 | BASEL, SWITZERLAND 1959 1955 | BEIJING, CHINA 2002 1998 | BELGRADE, YUGOSLAVIA 1959 | BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL 1987 | BERKELEY, CA 1960 1921 | BERLIN, GERMANY 2005 2000 1996 The Global Orchestra REPort 1993 1988 1985 1980 1976 1975 1968 1960 1959 1955 1930 | BERNE, SWITZERLAND 1955 | BETHEL, NY 2006 | BETHLEHEM, PA 1925 | BINGHAMTON, NY 1999 1912 | BIRMINGHAM, AL 1960 1954 1949 1947 1921 1916 | BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND 1995 | BISMARK, ND 1921 | BLOOMINGTON, IN 1972 1949 | BOGOTA, COLOMBIA 1987 1958 | BONN, GERMANY 2005 -

Lincoln Center 2013/14 Annual Report

Lincoln Center 2013/14 More than 5,000 people came to Hearst Plaza for the world premiere performances of John Luther Adams’s Sila: The Breath of the World, a commission for Lincoln Center Out of Doors and the Mostly Mozart Festival in the Paul Milstein Pool and Terrace, Laurie M. Tisch Wallpaper Illumination Lawn, and Barclays Capital Grove. B Lincoln Center Lincoln Center 1 to prepare, certify, and place much-needed, highly qualified music, dance, theater, and visual arts teachers in New York City’s public schools. Helping families engage with the performing arts is a long-term investment both in their own lives, and in the future of Lincoln Center; the young families we reach today are more likely to fill our halls in years ahead. This summer’s Lincoln Center Out of Doors season, with more than 100 events, was rich in family-friendly productions and free activities. Multiple generations enjoyed the Deep Roots of Rock & Roll concert and Baby Loves Disco, a dance party for toddlers and their parents. These programs were offered free, along with weekly Target® Free Thursdays and monthly Meet the Artist Saturdays in the David Rubenstein Atrium. We will be launching Family-Linc and other initiatives in the coming months. We are also expanding our use of digital technology to connect Lincoln Center with an ever-widening audience. During Lincoln Center Out of Doors, a quarter of a million people enjoyed our live concerts, and tens of thousands more watched our live streams of the memorial tribute concert to Pete and Toshi Seeger, and of performances by Jed Bernstein and Katherine Farley Dear Friends, artists like Cassandra Wilson and Rosanne Cash. -

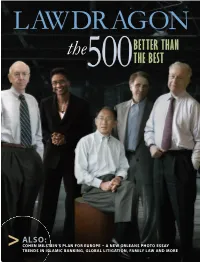

Better Than the Best

LAWDRAGONLAWDRAGON BETTER THAN the500 THE BEST ALSO: > COHEN MILSTEIN’S PLAN FOR EUROPE – A NEW ORLEANS PHOTO ESSAY TRENDS IN ISLAMIC BANKING, GLOBAL LITIGATION, FAMILY LAW AND MORE Strength By Your Side® An aggressive and experienced plaintiffs’ law firm devoted to representing victims everywhere. No fee until we win. The resources to win. Over $8 billion in verdicts and settlements Largest products liability personal injury verdict in 310-477-1700 history - $4.9 Billion 866-992-1700 Largest tire defect verdict in history - $56 million 5 verdicts and settlements in excess of $10 www.PSandB.com million in last two years More than 35 verdicts and settlements in excess of $1 million in last two years One of Top 12 Plaintiffs' Firms in Nation -- National Law Journal 100 Most Influential Lawyers in Nation -- National Law Journal Best Lawyers in America -- American Lawyer Media Top 100 Lawyers in California -- Daily Journal Trial Lawyer of the Year -- Consumer Attorneys of Los Angeles Best Lawyers in Los Angeles -- Los Angeles Times Major litigation is rarely straightforward. WORKING WITH YOUR LAW FIRM SHOULD BE. Major litigation can be a stressful journey, involving high-risk exposure and unpredictable results. You need lawyers who will simplify the process—not complicate it further. At Winston & Strawn we’re committed to helping our clients fi nd the most direct route to a successful outcome. When you’re faced with complex litigation, choose a law fi rm that will help you chart the right course. Choose Winston & Strawn. Chicago Geneva London Los Angeles Moscow New York Paris San Francisco Washington, D.C. -

32409 New Press Catalog Spring 2015.Indd

Contents BY TITLE BY AUTHOR Answering the Call 29 Abrahamian, Ervand 24 The Boy Who Could Change the World 16–17 Carr, Matthew 6–7 The Coup 24 Coverdale, Linda 12 Democracy in the Dark 11 Echenoz, Jean 12 Divided 28 Fiss, Owen 25 Don’t Hope, Don’t Fear, Don’t Beg 12–13 Fredrickson, Caroline 15 Fear and the Muse Kept Watch 20–21 Gardner, Lloyd C. 26–27 Fukushima 4 Glastris, Paul 2–3 Madam Ambassador 18 Goldberg, Rita 9 The Math Myth 14 Grove, Tara 5 Motherland 9 Hacker, Andrew 14 The Other College Guide 2–3 Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks 29 Out of Sight 23 Horwitz, Julia 19 Privacy in the Modern Age 19 Johnston, David Cay 28 The Queen’s Caprice 10 Jones, Nathaniel R. Jones 29 Rich Media, Poor Democracy 22 Kounalakis, Eleni Tsakopoulos 18 Sherman’s Ghost 6–7 Lessig, Lawrence 16–17 Syria 8 Lochbaum, David 4 Under the Bus 15 Loomis, Eric 23 A War Like No Other 25 Lyman, Edwin 4 The War on Leakers 26–27 McChesney, Robert W. 20–21 The World Is Waiting for You 5 McHugo, John 8 McSmith, Andy 21 Ostrer, Isabel 5 Rotenberg, Marc 19 Schwartz Jr., Fredrick A. O. 13 Scott, Jeramie 19 Staff of the Washington Monthly 2–3 Stewart, Ben 12–13 Stranahan, Susan Q. 4 Sutton, Trevor 25 Swartz, Aaron 16–17 Sweetland, Jane 2–3 Union of Concerned Scientists 4 BACKLIST 31–33 FOREIGN RIGHTS 30 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 34–36 Did You Know? Just because a school encourages you to apply doesn’t mean they actually want you. -

The New Press Index First Book Published: Race: How Blacks and Whites Think and Feel About the American Obsession by Studs Terkel (1992)

The New Press Index First book published: Race: How Blacks and Whites Think and Feel About the American Obsession by Studs Terkel (1992) Number of employees: 18 Number of titles The New Press has published since its inception: 1,000 Top all-time New Press bestsellers: Lies My Teacher Told Me by James Loewen, Other People’s Children by Lisa Delpit, Dr. Seuss Goes to War by Richard Minear Bestselling e-book author: Henning Mankell Book that caused the U.S. Supreme Court to send a cease-and-desist letter to The New Press: May It Please the Court: Live Recordings and Transcripts of Landmark Oral Arguments edited by Peter Irons and Stephanie Guitton TNP title that won the most prizes: Embracing Defeat by John Dower (Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, Bancroft Prize, Mark Lynton History Prize, Los Angeles Times Book Prize) Number of books with the word “war” in the title: 41 Number of books with the word “peace” in the title: 2 (1 of which also contained “war”) Number of books with the word “love” in the title: 3 Most recent major prizes won: 2011 NAACP Image Award for The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander and the 2011 Francis Parkman Prize for Stayin’ Alive by Jefferson Cowie Percentage of TNP books that are commissioned (versus acquired in manuscript form): 60+ First hardcover printing of The New Jim Crow in January 2010: 3,000 copies Copies of The New Jim Crow now in print: 175,000 Number of weeks The New Jim Crow paperback has been on the New York Times nonfiction paperback bestseller list: 8 weeks and counting Number of languages into which TNP books have been translated: 24 Number of not-for-profit organizations with which TNP has collaborated: 303 Cumulative revenue since 1992: $75,000,000 Number of graduates from TNP Diversity in Publishing internship program: 526 Top five foundation funders: the John D. -

Silverstein's Army

LIFETIMETHE ACHIEVERS AM LAW www.americanlawyer.com SEPTEMBER 2007 UP FROM THE ASHES It took Wachtell and Lipton, plus 70 of their lawyers, to help Larry Silverstein start rebuilding Ground Zero. By Ben Hallman The Biovail Botch: How a hedge fund suit became a law firm disaster. What associates earn: A city-by-city report. Cover_0907_LO.indd 2 8/15/07 12:32:46 PM WACHTELL, LIPTON DEDICATED MORE LAWYERS TO HELPING THAN TO ANY OTHER PROJECT IN ITS HISTORY. AFTER SIX YEARS IS FINALLY BREAKING GROUND. SILVERSTEIN’S ARMY SILVERSTEIN’S SILVERSTEIN’S ARMY SILVERSTEIN’S F-WTC_0907_LO**NEW.indd 84 8/15/07 2:09:53 PM LARRY SILVERSTEIN REBUILD AT GROUND ZERO OF HEAVY FIGHTING, THE FIRM’S BIGGEST CLIENT BY BEN HALLMAN PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL J.N. BOWLES AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER CONSTRUCTION SITE FROM LEFT: PETER HEIN, BEN GERMANA, JONATHAN MOSES, ADAM EMMERICH, MARTIN LIPTON, LARRY SILVERSTEIN, MARC WOLINSKY, BERNARD NUSSBAUM, ROBIN PANOVKA, HERBERT WACHTELL, ERIC ROTH, AND MICHAEL LEVY. F-WTC_0907_LO**NEW.indd 85 8/15/07 2:10:33 PM LARRY SILVERSTEIN ISN’T OFTEN AWAKE PAST 10 P.M., BUT FOR THIS, THE MARCH 14, 2006, MEETING THAT WOULD DETERMINE AT LONG LAST WHAT PART HE WOULD PLAY IN THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE WORLD TRADE CENTER, HE WAS WILLING TO MAKE AN EXCEPTION. Rebuilding was the developer’s dream— the most demanding project that ACHTELL IS THE WORLD’S PRE- and his right, according to his lawyers from Wachtell, Lipton has ever under- eminent M&A firm, home to the Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. -

Law School’S Vision

IN THIS ISSUE Furman Hall Opens: The Architecture of a Law School’s Vision. The Creative Counsel: Professor Burt Neuborne reflects on his NYU career as a litigating academic. Law School Top Criminal Minds: THE MAGAZINE OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITY A world-class faculty makes the case for NYU. SCHOOL OF LAW AUTUMN 2004 Partners in Crime On Our Cover Criminal Law Personified: Here’s how to make a professor proud. NAACP Legal Defense Fund law- yer, Vanita Gupta (’01), the subject of Turning the Tables in Tulia, on page 53, confers with co-coun- sel during the course of her high-stakes bid to free 35 wrongly-convicted citizens of Tulia, Texas. The lawyer facing Gupta in the sketch is another NYU School of Law graduate, Adam Levin (’97), who took the case pro bono for D.C. firm Hogan & Hartson. Levin is now one of the firm’s senior associates. Artist Marilyn Church has covered famous court- room spectacles including trials involving Robert Chambers, John Gotti, and Jean Harris of Scars- dale Diet fame—since the seventies. Her work is often on ABC and in The New York Times, and has been published in Fortune, Esquire, Time, and Newsweek. Message from Dean Revesz he Law School continues to astonish me with its vitality. Having completed my second year of stewardship as dean, I feel so grateful for the privilege of learning and interacting with the various communities that comprise the T NYU School of Law. In one extraordinary week last spring, for example, I first welcomed James Wolfensohn, the president of the World Bank, to an important conference on Human Rights and Development. -

New York Philharmonic Annual Report 2007 Great

NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ANNUAL REPORT 2007 GREAT COLLABORATIONS 2 Contents From top: The Lincoln Center Plaza 2 On Collaboration: From the Chairman & the President projection of Music Director Lorin 2006–07 Season Concerts & Attendance Maazel conducting the New York Philharmonic’s Gala Opening Night 4 Musical Alliance: Lorin Maazel & the Philharmonic Concert, September 13, 2006. 6 Relationships Old & New: In the Spotlight Conductor Alan Gilbert, who was named the next Philharmonic Featured Artists in the 2006–07 Season Music Director on July 18, 2007. 8 Future Partnership: Alan Gilbert & the Orchestra 9 Collaborative Inspirations: Composers, Performers & Commissioners 10 Collaborative Productions: Film, Opera & Musical Theater 12 Philharmonic Partners: Onstage & Off 14 A Joint Effort: Media 15 A Fellowship of Educators: Impacting Thousands 16 The Ultimate Team: The Orchestra 18 About the Board 20 Lifetime Gifts 22 Leonard Bernstein Circle 23 Endowment Fund 24 Annual Fund 32 Education Fund 33 Heritage Society 34 Honor and Memorial Gifts 35 Volunteer Council 36 Independent Auditors’ Report 46 Staff A Global Partner: Credit Suisse New York Philharmonic On June 4, 2007, the New York Philharmonic proudly Avery Fisher Hall announced that Credit Suisse, one of the world’s leading banks, 10 Lincoln Center Plaza would become the Orchestra’s first-ever and exclusive Global Sponsor, New York, NY 10023-6970 effective September 2007. With an active presence in more than 50 countries, Credit Suisse’s perspective is both local and global, and its Telephone: (212) 875-5900 continuing commitment to a partnership with the New York Fax: (212) 875-5717 Philharmonic and other prominent cultural institutions is part of its broader effort to play an engaged, positive role in the communities of nyphil.org which it is a part. -

The Law School Community Looks Forward to Sup·Porte : Verb Welcoming You Back to Washington Square

Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, W The good from evil Auschwitz survivor Thomas Law School & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Weil, Gots Buergenthal ’60 has spent his life Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Make your mark. Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jac The avenging injustice with justice. a new legal movement Empirical Legal Studies uses Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP These firms did. Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP | THE MAGAZINE OF THE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW OF SCHOOL UNIVERSITY YORK NEW THE OF MAGAZINE THE quantitative data to analyze Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen Lawthe magazine of the new york School university school of law • autumn 2008 thorny public policy problems. al & Manges LLP Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher Garrison LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Wa illkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP Paul Weiss & Reindel LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Cravath,Swaine arton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP & Katz Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Willkie Farr & Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, & Manges LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wacht Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Cahill & aul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & CromwellThe Wall LLP of HonorWachtell, Gordon & Reindel LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz WillkieTo find Farr out what & your Gallagher firm can do LLP to be acknowledged on the & Reindel LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind,Wall of Honor, Wharton please contact & Garri Marsha Metrinko at (212) 998-6485 or Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Weil,[email protected].