Tawa'ovi Community Development Projectprogrammatic Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Gila Region, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 498 THE LOWER GILA REGION, ARIZONA A GEOGBAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDBOLOGIC BECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PIACES BY CLYDE P. ROSS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 50 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAT 11, 1822 CONTENTS. I Page. Preface, by O. E. Melnzer_____________ __ xr Introduction_ _ ___ __ _ 1 Location and extent of the region_____._________ _ J. Scope of the report- 1 Plan _________________________________ 1 General chapters _ __ ___ _ '. , 1 ' Route'descriptions and logs ___ __ _ 2 Chapter on watering places _ , 3 Maps_____________,_______,_______._____ 3 Acknowledgments ______________'- __________,______ 4 General features of the region___ _ ______ _ ., _ _ 4 Climate__,_______________________________ 4 History _____'_____________________________,_ 7 Industrial development___ ____ _ _ _ __ _ 12 Mining __________________________________ 12 Agriculture__-_______'.____________________ 13 Stock raising __ 15 Flora _____________________________________ 15 Fauna _________________________ ,_________ 16 Topography . _ ___ _, 17 Geology_____________ _ _ '. ___ 19 Bock formations. _ _ '. __ '_ ----,----- 20 Basal complex___________, _____ 1 L __. 20 Tertiary lavas ___________________ _____ 21 Tertiary sedimentary formations___T_____1___,r 23 Quaternary sedimentary formations _'__ _ r- 24 > Quaternary basalt ______________._________ 27 Structure _______________________ ______ 27 Geologic history _____ _____________ _ _____ 28 Early pre-Cambrian time______________________ . -

Chapter 7 the Enduring Hopi

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law History, Department of September 2008 Chapter 7 The Enduring Hopi Peter Iverson Arizona State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hopination Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Iverson, Peter, "Chapter 7 The Enduring Hopi" (2008). HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hopination/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CHAPTER 7 The Enduring Hopi Peter Iverson “What then is the meaning of the tricentennial observance? It is a reaffirmation of continuity and hope for the collective Hopi future.” The Hopi world is centered on and around three mesas in northeastern Arizona named First, Sec- ond, and Third. It is at first glance a harsh and rugged land, not always pleasing to the untrained eye. Prosperity here can only be realized with patience, determination, and a belief in tomorrow.1 For over 400 years, the Hopis have confronted the incursion of outside non-Indian societies. The Spanish entered Hopi country as early as 1540. Then part of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s explor- ing party invaded the area with characteristic boldness and superciliousness. About twenty Spaniards, including a Franciscan missionary, confronted some of the people who resided in the seven villages that now comprise the Hopi domain, and under the leadership of Pedro de Tovar, the Spanish over- came Hopi resistance, severely damaging the village of Kawaiokuh, and winning unwilling surrender. -

Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of Oklahoma I

Information Series #1, June 1998 Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of OklahomaI Kenneth S. Johnson2 INTRODUCTION valleys, hills, and plains throughout most of the re mainder of Oklahoma (Fig. 1). All the major lakes and Mountains and streams define the landscape of reservoirs of Oklahoma are man-made, and they are Oklahoma (Fig. 1). The mountains consist mainly of important for flood contr()l, water supply, recreation, resistant rock masses that were folded, faulted, and and generation of hydroelectric power. Natural lakes thrust upward in the geologic past (Fig. 2), whereas in Oklahoma are limited to oxbow lakes along major the streams have persisted in eroding less-resistant streams and to playa lakes in the High Plains region rock units and lowering the landscape to form broad of the west. Alphabetical List of20 Lakes with Largest Surface Area (from Oklahoma Water Atlas, Oklahoma Water Resources Board) 1. Broken Bow 11. Lake 0' The Cherokees 2. Canton 12. Oologah 3. Eufaula 13. Robert s. Kerr 4. Fort Gibson 14. Sardis 5. Foss 15. Skiatook 6. Great Salt Plains 16. Tenkiller Ferry ·7. Hudson 17. Texoma 8. Hugo 18. Waurika 9. Kaw 19. Webbers Falls 10. Keystone 20. Wister Modified from Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, by John W. Morris, Charles R. Goins, and Edwin C. 25 McReynolds. Copyright © 1986 by the University I of Oklahoma Press. o 40 80Km Figure 1. Mountains, streams, and principal lakes of Oklahoma. lReprinted from Oklahoma Geology Notes (1993), vol. 53, no. 5, p. 180-188. The Notes article was reprinted and expanded from Oklahoma Almanac, 1993-1994, Oklahoma Department of Lihraries, p. -

Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. July 22, 2021 Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015 Effective March 17, 2021 The federal Clean Water Act (CWA) requires states and federally recognized Indian tribes to adopt water quality standards in order to "restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's Waters" (CWA, 1988). The attached WQS document is in effect for Clean Water Act purposes with the exception of the following provisions. Navajo Nation’s previously approved criteria for these provisions remain the applicable for CWA purposes. The “Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015” (NNSWQS 2015) made changes amendments to the “Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2007” (NNSWQS 2007). For federal Clean Water Act permitting purposes, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) must approve these changes to the NNSWQS 2007 which are found in the NNSWQS 2015. The USEPA did not approve of three specific changes which were made to the NNSWQS 2007 and are in the NNSWQS 2015. (October 15, 2020 Letter from USEPA to Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency). The three specific changes which USEPA did not accept are: 1) Aquatic and Wildlife Habitat Designated Use - Suspended Solids Changes (NNSWQS 2015 Section 207.E) The suspended soils standard for aquatic and wildlife habitat designated use was changed to only apply to flowing (lotic) surface waters and not to non-flowing (lentic) surface waters. -

15 Landscape and Aesthetics Corridor Plan

- 15 landscape and aesthetics corridor plan I-15 FROM PRIMM TO MESQUITE CORRIDOR PLAN DESIGN WORKSHOP MacKay & Somps JW Zunino & Assoc. CH2MHill Jones & Jones August 3, 2005 1-15 corridor plan Endorsement MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR OF NEVADA MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR KENNY C. GUINN NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JEFFREY FONTAINE, P.E. On June 30, 2002, the Nevada Department of Transportation adopted It is NDOT's responsibility to ensure that landscaping and aesthetics as policy, "Pattern and Palette of Place: A Landscape and Aesthetics are an important consideration in building and retrofitting our high- Master Plan for the Nevada State Highway System". Now, the second way system. This Landscape and Aesthetics Corridor Plan for I-15 in phase of planning is complete. This I-15 Landscape and Aesthetics Northern Nevada helps realize our vision for the future appearance of Corridor Plan represents a major step forward for the Landscape and our highways. The plan will provide the guidance for our own design Aesthetics program created by the Master Plan. It is significant teams as well as help Nevada's citizens play an important role in the because it involves local public agencies and citizens in the planning context-sensitive solutions for today's transportation needs. process so that Nevada's highways truly represent the State and its Together, we will ensure our highways reflect Nevada's distinctive people. The Corridor Plan will be the primary management tool used heritage, landscape, and culture. to guide funding allocations, promotes appropriate aesthetic design, and provides for the incorporation of highway elements that unique- ly express Nevada's landscape, communities, and cities, as well as its people. -

Tse' Nikani Draft Corridor Management

Tse'nikani Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan DRAFT August 2013 Introduction Purpose Tse’nikani Scenic Byway was established The purpose of a byway corridor as an Arizona Byway in 2005 and given the management plan is not to create more name Tse’nikani ‘Flat Mesa Rock’ Scenic regulations or taxes. Rather, a corridor Byway. management plan documents the goals, strategies, and responsibilities for preserving and enhancing the byway’s most Byway Description valuable qualities. Promoting tourism can Tse’nikani Scenic Byway, U.S. Highway be one target, but so are issues of safety or (US) 191 is located in northeast Arizona preserving historic or cultural structures. in Apache County and entirely within the 160 The Corridor Management Plan can: Navajo Nation. The portion of US 191 that 1 160 Tse’nikani is a designated Arizona Scenic Byway is Scenic Road ◊ document community interest from Milepost (MP) 467.0, south of Many ◊ document existing conditions and Farms, to MP 510.4, at the junction with history US 160, near Mexican Water. The highway ◊ guide enhancement and safety is the primary route to access Canyon de improvement projects ARIZONA Chelly National Monument, about 13 miles mexico new south of the south end of the byway. ◊ promote partnerships for conservation Chinle and enhancement activities US 191 is a two-lane asphalt paved road for ◊ suggest resources for project development almost its entire length with no median and programs and few left-turn lanes. The roadway is ◊ promote coordination between residents, managed by the Arizona Department communities, and agencies of Transportation (ADOT) through the 264 Ganado ◊ support application for National Scenic Navajo Nation. -

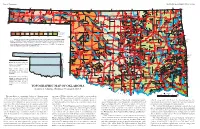

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Hydrogeology and Water Resources of the Hopi Reservation, Arizona

Hydrogeology and Water Resources of the Hopi Reservation, Arizona Hopi Water Resources Program Lionel Puhuyesva – Director James A. Duffield R.G. - Hydrogeologist The Hopi Reservation Where the Hopi have resided for over 1,500 years. A land of high desert. Marc Reisner in Cadillac Desert “A semidesert with a desert heart” Water in the High Desert Where residents depend on groundwater. A land of violent summer thunderstorms Current Reservation Boundaries The Hopi Reservation is located entirely in the State of Arizona. District Six, reserved exclusively for Hopi use, consists of 2,500 square miles. Other holdings include the joint use area with the surrounding Navajo Reservation and new land ranches near Flagstaff. Hopi District Six, the Hopi Mesas The broad plateau of Black Mesa is dissected by several northeast oriented canyons that divide the plateau into fingers or mesas. The Hopi Villages are located on these southwest oriented fingers on First, Second, and Third Mesa. The Villages of Upper and Lower Moenkopi are located to the west of the main portion of the Reservation near Tuba City. The Reservation is Located in the Colorado Plateau Physiographic Region A region of relatively un-deformed rocks defined by the Grand Canyon geology. It is formed by a thick crustal block that has been resistant to deformation. This has retained the original horizontal layering of the rock. Layers of Gently Folded Sedimentary Rocks are Stacked Atop Each Other. On the Hopi Reservation Wide Mesas Are Interspersed with Broad Valleys The southern part of the Reservation is lower and semi-arid. The northern portion of the reservation includes the higher reaches of Black Mesa where the elevation approaches 7,000 feet and much of the winter precipiation falls as snow. -

3 March 1999

NAVAJO NATION SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS 2007 (Photograph of the Little Colorado River near Grand Falls on January 4, 2005) Prepared by: Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency Water Quality Program Post Office Box 339 Window Rock, Arizona 86515 (928) 871-7690 Passed by Navajo Nation Resources Committee on May 13, 2008 Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2007 Navajo Nation EPA Water Quality Program TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS - GENERAL PROVISIONS § 101 TITLE ................................................................................................................................ 1 § 102 AUTHORITY .................................................................................................................... 1 § 103 PURPOSE.......................................................................................................................... 1 § 104 DEFINITIONS................................................................................................................... 1 § 105 SEVERABILITY............................................................................................................... 6 PART II SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS § 201 ANTIDEGRADATION POLICY ..................................................................................... 7 § 202 NARRATIVE SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS ...................................... 7 § 203 IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ............................................................................................ 9 § 204 NARRATIVE -

NAVAJO NATION: Tuba City, Arizona PROGRAM HANDBOOK

www.amizade.org 412-586-4986 [email protected] PO Box 6894, 343 Stansbury Hall, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA NAVAJO NATION: Tuba City, Arizona PROGRAM HANDBOOK Introduction This Handbook was written to provide you with useful information regarding your participation in an Amizade sponsored program. It answers many of the frequently asked questions by previous participants. We encourage your feedback on how it can be improved for future participants. Please read this entire handbook carefully and contact our office if you have any questions. Amizade’s Mission & Vision Amizade encourages intercultural exploration and understanding through community-driven service-learning courses and volunteer programs. Amizade imagines a world in which all people have the opportunity to explore and grow, realize their ability to make change, and embrace their responsibility to build a better world. Amizade’s Commitment At the heart of Amizade is the sincere belief that intercultural understanding & the development of global citizens is essential to our increasingly connected global world. We are committed to providing you with an intercultural experience that allows you to make concrete contributions to a community resulting in a deeper understanding of your role in the global community. Approach to Service Ethic of Service Amizade strives to promote an “ethic of service” on all our programs. This means that we envision the entire experience as one of service to our fellow human beings. There will be scheduled time for completing service projects on each program but we also encourage you to carry your ethic of service with you throughout the program. You can do this by volunteering to help with food preparation, cleaning, or various other daily tasks. -

Magyar Földrajzi Nevek Angol Nyelvre Fordítása

Magyar földrajzi nevek angol nyelvre fordítása Diplomamunka Térképész mesterszak készítette: Horváth Gábor Roland témavezető: Dr. Gercsák Gábor, egyetemi docens Térképtudományi és Geoinformatikai Tanszék Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem 2018. EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM INFORMATIKAI KAR TÉRKÉPTUDOMÁNYI ÉS GEOINFORMATIKAI TANSZÉK DIPLOMAMUNKA-TÉMA BEJELENTŐ Név: Neptun kód: Szak: térképész MSc Témavezető neve: munkahelyének neve és címe: beosztása és iskolai végzettsége: A dolgozat címe: A témavezetést vállalom. .......................................................... (a témavezető aláírása) Kérem a diplomamunka témájának jóváhagyását. Budapest, 20…………………... ........................................................... (a hallgató aláírása) A diplomamunka-témát az Informatikai Kar jóváhagyta. Budapest, 20…………………… …………………………………….. (témát engedélyező tanszék vezetője) Tartalomjegyzék Címlap ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Témabejelentő ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Tartalomjegyzék ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Bevezetés ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1. fejezet: A jelenlegi helyzet ............................................................................................................. -

EPA Community Involvement Plan for Tuba City Dump Cleanup Site

TUBA CITY DUMP COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT PLAN FEBRUARY 2013 INTRODUCTION Under the Federal Superfund program, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) is overseeing a comprehensive environmental investigation and evaluation of cleanup options for the Tuba City Dump. This Community Involvement Plan (CIP) outlines specific outreach activities to address community concerns and meet the following goals: • Encourage community interest and give the public the opportunity to provide meaningful input into site cleanup decisions; • Provide to the Navajo and Hopi communities accurate, timely and understand- able information about what we learn in our investigations, in a manner considerate to their preference and culture; • Respect and consider community and tribal leaders’ input and feedback on USEPA’s process as it is being carried out. To put this plan together, USEPA began by conducting a series of community interviews in March 2012 with residents, elected officials and other stakeholders in the area. Many interviews were conducted with individual residents and tribal leaders in the Upper Village of Moenkopi, and in the Moencopi Village – Lower (also known as Lower Moencopi), within the Hopi Tribe. Earlier interviews, in 2011, were conducted with residents of Lower Moencopi. USEPA did not conduct interviews with residents on the Navajo Reservation because many of the Navajo residents had been interviewed recently by Navajo Nation EPA and USEPA for site history information. Out of respect for these residents, the Navajo Nation EPA asked USEPA to coordinate the development of the CIP through their Community Involvement Coordinator because they are already familiar with the Navajo residents’ preferences for receiving information and staying involved with site decisions.