Weimar Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

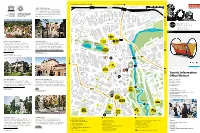

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

Douglas Peifer on Munich 1919: Diary of a Revolution

Victor Klemperer. Munich 1919: Diary of a Revolution. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017. 220 pp. $25.00, cloth, ISBN 978-1-5095-1058-0. Reviewed by Douglas Peifer Published on H-War (December, 2017) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) Victor Klemperer’s diary created quite a stir came an increasingly desperate struggle. Translat‐ when frst published in Germany in 1995. Klem‐ ed into English in 1998/99, his frst-person reflec‐ perer’s diary entries for the period 1933-45 have tions of life in the Third Reich have been used ex‐ been used extensively by scholars of the Third Re‐ tensively by scholars such as Richad J. Evans, Saul ich and the Holocaust to illustrate how Nazi ideol‐ Friedländer, and Omer Bartov.[1] ogy and racial policies affected even thoroughly Klemperer’s Munich 1919: Diary of a Revolu‐ assimilated, converted Jews. Klemperer, the son tion provides a remarkable eyewitness account of of a rabbi, was born in Wilhelmine Germany. His an earlier crisis in German history, one connected education, professional development, and life to the Third Reich by the myths and memories choices were thoroughly bourgeois, with Klem‐ that ideologues on the far right exploited through‐ perer’s conversion to Protestantism signaling his out the Weimar era. Two days before the abdica‐ self-identification with German culture and his tion of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the declaration of a desire to assimilate. Klemperer attended Gymna‐ German Republic in Berlin on November 9, 1918, sium in Berlin and Landsberg on the Warthe, worker and soldier councils in Munich toppled studied German and Romance philology in Mu‐ the 738-year Wittelsbach dynasty in Bavaria. -

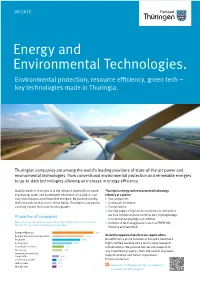

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book

Paper 3 Weimar and Nazi Germany Revision Guide and Student Activity Book Section 1 – Weimar Republic 1919-1929 What was Germany like before and after the First World War? Before the war After the war The Germans were a proud people. The proud German army was defeated. Their Kaiser, a virtual dictator, was celebrated for his achievements. The Kaiser had abdicated (stood down). The army was probably the finest in the world German people were surviving on turnips and bread (mixed with sawdust). They had a strong economy with prospering businesses and a well-educated, well-fed A flu epidemic was sweeping the country, killing workforce. thousands of people already weakened by rations. Germany was a superpower, being ruled by a Germany declared a republic, a new government dictatorship. based around the idea of democracy. The first leader of this republic was Ebert. His job was to lead a temporary government to create a new CONSTITUTION (SET OF RULES ON HOW TO RUN A COUNTRY) Exam Practice - Give two things you can infer from Source A about how well Germany was being governed in November 1918. (4 marks) From the papers of Jan Smuts, a South African politician who visited Germany in 1918 “… mother-land of our civilisation (Germany) lies in ruins, exhausted by the most terrible struggle in history, with its peoples broke, starving, despairing, from sheer nervous exhaustion, mechanically struggling forward along the paths of anarchy (disorder with no strong authority) and war.” Inference 1: Details in the source that back this up: Inference 2: Details in the source that back this up: On the 11th November, Ebert and the new republic signed the armistice. -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

The Failed Post-War Experiment: How Contemporary Scholars Address the Impact of Allied Denazification on Post-World War Ii Germany

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Master's Theses and Essays 2019 THE FAILED POST-WAR EXPERIMENT: HOW CONTEMPORARY SCHOLARS ADDRESS THE IMPACT OF ALLIED DENAZIFICATION ON POST-WORLD WAR II GERMANY Alicia Mayer Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the History Commons THE FAILED POST-WAR EXPERIMENT: HOW CONTEMPORARY SCHOLARS ADDRESS THE IMPACT OF ALLIED DENAZIFICATION ON POST-WORLD WAR II GERMANY An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Alicia Mayer 2020 As the tide changed during World War II in the European theater from favoring an Axis victory to an Allied one, the British, American, and Soviet governments created a plan to purge Germany of its Nazi ideology. Furthermore, the Allies agreed to reconstruct Germany so a regime like the Nazis could never come to power again. The Allied Powers met at three major summits at Teheran (November 28-December 1,1943), Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and Potsdam (July 17-August 2, 1945) to discuss the occupation period and reconstruction of all aspects of German society. The policy of denazification was agreed upon by the Big Three, but due to their political differences, denazification took different forms in each occupation zone. Within all four Allied zones, there was a balancing act between denazification and the urgency to help a war-stricken population in Germany. This literature review focuses specifically on how scholars conceptualize the policy of denazification and its legacy on German society. -

At Berne: Kurt Eisner, the Opposition and the Reconstruction of the International

ROBERT F. WHEELER THE FAILURE OF "TRUTH AND CLARITY" AT BERNE: KURT EISNER, THE OPPOSITION AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE INTERNATIONAL To better understand why Marxist Internationalism took on the forms that it did during the revolutionary epoch that followed World War I, it is useful to reconsider the "International Labor and Socialist Con- ference" that met at Berne from January 26 to February 10,1919. This gathering not only set its mark on the "reconstruction" of the Second International, it also influenced both the formation and the development of the Communist International. It is difficult, however, to comprehend fully what transpired at Berne unless the crucial role taken in the deliberations by Kurt Eisner, on the one hand, and the Zimmerwaldian Opposition, on the other, is recognized. To a much greater extent than has generally been realized, the immediate success and the ultimate failure of the Conference depended on the Bavarian Minister President and the loosely structured opposition group to his Left. Nevertheless every scholarly study of the Conference to date, including Arno Mayer's excellent treatment of the "Stillborn Berne Conference", tends to un- derestimate Eisner's impact while largely ignoring the very existence of the Zimmerwaldian Opposition.1 Yet, if these two elements are neglected it becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to fathom the real significance of Berne. Consequently there is a need to reevaluate 1 In Mayer's case this would seem to be related to two factors: first, the context in which he examines Berne, namely the attempt by Allied labor leaders to influence the Paris Peace Conference; and second, his reliance on English and French accounts of the Conference. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933 Fuad Aleskerov1, Manfred J. Holler2 and Rita Kamalova3 Abstract: ................................................................................................................................................2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................2 2. The Weimar Germany 1919-1933: A brief history of socio-economic performance .......................3 3. Political system..................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Electoral system for the Reichstag ..................................................................................................6 3.3 Political parties ................................................................................................................................6 3.3.1 The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).....................................................................7 3.3.2 The Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands – KPD)...............8 3.3.3 The German Democratic Party (Deutsche Demokratische Partei – DDP)...............................9 3.3.4 The Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei – Zentrum) .......................................................10 3.3.5 The German People's Party (Deutsche Volkspartei – DVP) ..................................................10 3.3.6 German-National People's Party (Deutsche -

The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama

The Secret School of War: The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian Johnson Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Jennifer Siegel, Advisor Peter Mansoor David Hoffmann Copyright by Ian Ona Johnson 2012 Abstract This paper explores the period of military cooperation between the Weimar Period German Army (the Reichswehr), and the Soviet Union. Between 1922 and 1933, four facilities were built in Russia by the two governments, where a variety of training and technological exercises were conducted. These facilities were particularly focused on advances in chemical and biological weapons, airplanes and tanks. The most influential of the four facilities was the tank testing and training grounds (Panzertruppenschule in the German) built along the Kama River, near Kazan in North- Central Russia. Led by German instructors, the school’s curriculum was based around lectures, war games, and technological testing. Soviet and German students studied and worked side by side; German officers in fact often wore the Soviet uniform while at the school, to show solidarity with their fellow officers. Among the German alumni of the school were many of the most famous practitioners of mobile warfare during the Second World War, such as Guderian, Manstein, Kleist and Model. This system of education proved highly innovative. During seven years of operation, the school produced a number of extremely important technological and tactical innovations. Among the new technologies were a new tank chassis system, superior guns, and - perhaps most importantly- a radio that could function within a tank. -

Introduction to the Weimar Republic

Handout Introduction to the Weimar Republic Directions: Write a D next to information about the Weimar Republic that represents characteristics of a democracy and an X next to information that describes problems or challenges for a democracy. From Monarchy to Democracy D X After World War I, Germany’s political leaders sought to transform Germany from a monarchy to a democracy, called the Weimar Republic (1918–1933). The Weimar Constitution divided power into three branches of government. Elections were held for the president and the Reichstag (the legislature), while the judicial branch was appointed. The Weimar Constitution D X Adopted on August 11, 1919, the new Weimar Constitution spelled out the “basic rights and ob- ligations” of government officials and the citizens they served. Most of those rights and obliga- tions had not existed in Germany under the kaiser, including equality before the law, freedom of religion, and privacy. Despite the inclusion of these rights in the Weimar Constitution, individual freedom was not fully protected. Old laws that denied freedoms continued, including laws that discriminated against homosexual men and “Gypsies” (the name, considered derogatory today, used to describe two groups of people called the Sinti and Roma). The Reichstag D X Germans voted for a party, rather than a candidate, to fill the Reichstag (the German legisla- ture). The elections determined the percentage of seats each party received in the Reichstag, but the parties themselves selected the individuals who filled each allotted seat. For example, if a party received 36% of the vote, they would get 36% of the seats in the Reichstag.