Frustration of Performance of Contracts: a Comparative and Analytic Study in Islamic Law and English Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Force Majeure and International Contracts, Including FIDIC

Force Majeure and Hardship Clauses in International Commercial Contracts in View of the Practice of the ICC Court of Arbitration Werner Melis* ICC ARBITRATION IS GENUINE international arbitration: The jurisdiction of the Court covers business disputes of an international character (Art.1(1) of its Rules)1; the arbitrators can be of any nationality (Art. 2), the parties are free to determine the law to be applied by the arbitrators to the merits of the dispute. In the absence of such determination by the parties, the arbitrators shall apply the law designated as the proper law by the rules of conflict which they deem appropriate (Art.13(3)). They shall have the power of an amiable compositeur only if the parties are agreed to give them such powers (Art.13 (4)). Finally, "in all cases the arbitrator[s] shall take account of the provisions of the contract and the relevant trade usages" (Art. 13 (5)). This international character of ICC arbitration is also reflected by the statistics issued at the Court's 60th anniversary, in October last year2: While in 1977 arbitrators under ICC Rules were nationals of 20 different countries, by 1982 the arbitrators involved in ICC cases came from 30 different countries; the 1982 break-down of the origin of parties according to geographic areas showed that 54 per cent came from Western Europe, 10 per cent from European socialist countries,17 per cent from the Americas and Australia,10 per cent from Arab coun- (...) ICC arbitration is therefore practiced by arbitrators coming from all over the world, who have to apply a large spectrum of national laws from many legal systems. -

DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. V. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. v. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js. Argued March 21Ðofficially released September 10, 2013 (Appeal from Superior Court, judicial district of Ansonia-Milford, Hon. John W. Moran, judge trial referee.) Linda L. Morkan, with whom, on the brief, was Christopher J. -

CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : V. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : v. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants. : NO. 95-1674 M E M O R A N D U M Reed, J. January 16, 1998 The Court issues this memorandum in support of its Order dated January 9, 1998 (Document No. 42), in which the Court denied the motion of defendants Harvey Levy (“Levy”), Suburban Therapy, Inc. (“ST”), and Suburban Medical Associates (“SM”) (collectively “the defendants”) for partial reconsideration of the Order dated December 19, 1997 (Document No. 38) and granted in part the renewed motion of plaintiff Frank Fumai (“Fumai”) in limine to exclude all evidence and argument at trial that pertains or relates to the defendants’ claim or defense that Fumai breached a fiduciary duty owed to Allegheny United Hospitals (“Allegheny”) in connection with the sale of the assets of ST and SM to Allegheny (Document No. 37). I. BACKGROUND The following background facts are undisputed.1 On November 1, 1990, Fumai entered into an agreement with the defendants whereby Fumai would receive a commission from the sale of capital stock or assets of ST and SM if he procured a purchaser or introduced a party to the defendants who later introduced or procured a purchaser. Under the agreement, Fumai would receive 10% of the purchase price of ST and 5% of the purchase price of SM for such a sale. At the time of the contract between Fumai and the defendants, the main business of ST was the management of physician care services, including management of SM. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

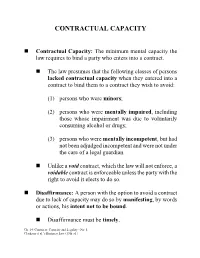

Contractual Capacity

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity the law requires to bind a party who enters into a contract. The law presumes that the following classes of persons lacked contractual capacity when they entered into a contract to bind them to a contract they wish to avoid: (1) persons who were minors; (2) persons who were mentally impaired, including those whose impairment was due to voluntarily consuming alcohol or drugs; (3) persons who were mentally incompetent, but had not been adjudged incompetent and were not under the care of a legal guardian. Unlike a void contract, which the law will not enforce, a voidable contract is enforceable unless the party with the right to avoid it elects to do so. Disaffirmance: A person with the option to avoid a contract due to lack of capacity may do so by manifesting, by words or actions, his intent not to be bound. Disaffirmance must be timely. Ch. 14: Contracts: Capacity and Legality - No. 1 Clarkson et al.’s Business Law (13th ed.) MINORITY Subject to certain exceptions, an unmarried legal minor (in most states, someone less than 18 years old) may avoid a contract that would bind him if he were an adult. Contracts entered into by young children and contracts for something the law permits only for adults (e.g., a contract to purchase cigarettes or alcohol) are generally void, rather than voidable. Right to Disaffirm: Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after he comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. -

Unit 6 – Contracts

Unit 6 – Contracts I. Definition A contract is a voluntary agreement between two or more parties that a court will enforce. The rights and obligations created by a contract apply only to the parties to the contract (i.e., those who agreed to them) and not to anyone else. II. Elements In order for a contract to be valid, certain elements must exist: (A) Competent parties. In order for a contract to be enforceable, the parties must have legal capacity. Even though most people can enter into binding agreements, there are some who must be protected from deception. The parties must be over the age of majority (18 under most state laws) and have sufficient mental capacity to understand the significance of the contract. Regarding the age requirement, if a minor enters a contract, that agreement can be voided by the minor but is binding on the other party, with some exceptions. (Contracts that a minor makes for necessaries such as food, clothing, shelter or transportation are generally enforceable.) This is called a voidable contract, which means that it will be valid (if all other elements are present) unless the minor wants to terminate it. The consequences of a minor avoiding a contract may be harsh to the other party. The minor need only return the subject matter of the contract to avoid the contract. if the subject matter of the contract is damaged the loss belongs to the nonavoiding party, not the minor. Regarding the mental capacity requirement, if the mental capacity of a party is so diminished that he cannot understand the nature and the consequences of the transaction, then that contract is also voidable (he can void it but the other party can not). -

Federalizing Contract Law

LCB_24_1_Article_5_Plass_Correction (Do Not Delete) 3/6/2020 10:06 AM FEDERALIZING CONTRACT LAW by Stephen A. Plass* Contract law is generally understood as state common law, supplemented by the Second Restatement of Contracts and Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code. It is regarded as an expression of personal liberty, anchored in the bar- gain and consideration model of the 19th century or classical period. However, for some time now, non-bargained or adhesion contracts have been the norm, and increasingly, the adjudication of legal rights and contractual remedies is controlled by privately determined arbitration rules. The widespread adoption of arbitral adjudication by businesses has been enthusiastically endorsed by the Supreme Court as consonant with the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”). How- ever, Court precedents have concluded that only bilateral or individualized arbitration promotes the goals of the FAA, while class arbitration is destruc- tive. Businesses and the Court have theorized that bilateral arbitration is an efficient process that reduces the transaction costs of all parties thereby permit- ting firms to reduce prices, create jobs, and innovate or improve products. But empirical research tells a different story. This Article discusses the constitu- tional contours of crafting common law for the FAA and its impact on state and federal laws. It shows that federal common law rules crafted for the FAA can operate to deny consumers and workers the neoclassical contractual guar- antee of a minimum adequate remedy and rob the federal and state govern- ments of billions of dollars in tax revenue. From FAA precedents the Article distills new rules of contract formation, interpretation, and enforcement and shows how these new rules undermine neoclassical limits on private control of legal remedies. -

Memorandum for Claimant (CUNEF)

Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros Twenty-Fourth Annual Willem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot COLEGIO UNIVERSITARIO DE ESTUDIOS FINANCIEROS Memorandum for CLAIMANT On behalf of: Wright Ltd, 232 Garrincha Street, Oceanside, Equatoriana Against: SantosDKG, 77 Avenida O Rei, Cafucopa, Mediterraneo Jessica Berzal • Claudia García • Luis Ortega Gutier Rettensteiner • Ana Sanmillán • Jose Usera I Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros II Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros LIST OF ABREVATIONS: ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution Agreement Development and Sales Agreement without the addendum Art./Artt. Article/s CAM-CCBC The Centre for Arbitration and Mediation of the Chamber of Commerce Brazil- Canada CEO Chief Executive Officer CFO Chief Financial Officer CISG United Nation Convention on the International Sales of Goods CoC Change of circumstances DSA Development and Sales Agreement, including the addendum EQD Equatorianan Dinar p. page para. paragraph RFA Request for Arbitration SFC Security for Costs UNCITRAL United Nations Commission on International Trade Law Model Law III Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros LIST OF AUTHORITIES: • Albaladejo, Manuel, Derecho Civil II: Derecho de Obligaciones, Edisofer (2011). Cited as “Albaladejo”; • Berger Bernard, Kellerhals Franz, Internationale und interne Schiedsgerichtsbarkeit in der Schweiz, Bern, 2006, p.518 , cited as “Berger & Kellerhals”; • Bezarević Pajić, Jelena and Lalatović Đorđević, Nataša, “Security for Costs in Investment Arbitration: Who Should Bear the Risk of an Impecunious Claimant?”; August 9, 2016, available at: http://kluwerarbitrationblog.com/2016/08/09/security- for-costs-in-investment-arbitration-who-should-bear-the-risk-of-an-impecunious- claimant/, cited as “ Bezarević Pajić & Lalatović Đorđević”; • Bonell, Michael Joachim, The UNIDROIT Initiative for the Progressive Codification of International Trade Law, 27 ICLQ 1978, at 413 et seq., available at http://www.trans-lex.org/119500. -

Force Majeure Tracker

Force majeure tracker April 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This guide has been prepared to address the substantial business and operational disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the unexpected nature of the outbreak, parties to commercial contracts may seek to invoke force majeure or similar legal concepts to excuse delay or non-performance. This guide gives a high-level comparative analysis of force majeure in 28 jurisdictions, together with alternative remedies that may apply depending on the governing law of the relevant contracts. If you have any additional questions, please do not hesitate to contact our practitioners listed throughout the document. Asia Pacific EMEA The Americas 2 ASIA PACIFIC Jo Delaney Zhou Xi Roberta Chan Cynthia Tang Angela Ang Australia China Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong +61 2 8922 5467 +86 10 5949 6019 +852 2846 2492 +852 2846 1708 +852 2846 1795 jo.delaney zhouxi roberta.chan cynthia.tang angela.ang @bakermckenzie.com @fenxunlaw.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com Andi Kadir Timur Sukirno Yoshiaki Muto Kherk Ying Chew Donemark Calimon Indonesia Indonesia Japan Malaysia Philippines +62 21 2960 8511 +62 21 2960 8500 +81 3 6271 9451 +603 2298 7933 +63 2 8819 4920 andi.kadir timur.sukirno yoshiaki.muto kherkying.chew donemark.calimon @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @wongpartners.com @quisumbingtorres.com Daljit Kaur Nandakumar Ponniya Henry Chang Pisut Attakamol Singapore Singapore Taiwan Thailand +65 6434 2255 +65 6434 2663 +886 2 2715 7259 + 66 2636 2000 x 3131 daljit.kaur nandakumar.ponniya henry.chang pisut.attakamol @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com Minh Tri Quach Fred Burke Vietnam Vietnam +84 24 3936 9605 +84 28 3520 2628 minhtri.quach frederick.burke @bmvn.com.vn @bakermckenzie.com 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 1 Is FM recognized in statute? If yes, what is impact of statutory rules on FM clauses in contracts? AUSTRALIA No statutory recognition. -

Relative Consent and Contract Law

18 NEV. L.J. 165, KIM - FINAL 12/15/17 12:41 PM RELATIVE CONSENT AND CONTRACT LAW Nancy S. Kim* What does it mean to consent? Consent is an essential component of contracts, yet its part in contract law is obscure. Despite its importance, there is no independ- ent doctrine of consent; rather, it plays a key, but ill-defined role in assessing doc- trines such as assent or duress. This Article addresses this significant omission in contract law by disassembling the meaning of contractual consent into three con- ditions: an intentional act or manifestation of consent, voluntariness and knowledge. This Article argues that consent can only be understood relative to these three conditions. Accordingly, consent is not merely a conclusion but a pro- cess and a dynamic that depends upon a variety of factors, including the relative blameworthiness of the parties, their relationship, third party effects and societal impact. This Article, through an examination of classic and modern cases, demon- strates how the concept of relative consent provides a coherent framework for un- derstanding contract law. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 166 I. CONSENT CONSTRUCTION AND CONSENT DESTRCUTION .......... 169 A. Consent Construction .......................................................... 170 1. Intentional Manifestation of Consent ........................... 171 2. The Knowledge Condition ............................................ 172 3. Voluntariness ............................................................... -

1 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT of MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL DIVISION in Re: CYPHERMINT, INC. Debtor ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Chapt

Case 10-04054 Doc 69 Filed 07/25/13 Entered 07/25/13 15:27:53 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 13 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 7 ) Case No. 08-42682-MSH CYPHERMINT, INC. ) ) Debtor ) ) ) JOSEPH H. BALDIGA, TRUSTEE ) ) Plaintiff ) Adversary Proceeding ) No. 10-04054 v. ) ) C.A. ACQUISITION CORP., C.A. ) ACQUISITION NEWCO, LLC, and ) PAYCASH MOBILE, LLC ) ) Defendants MEMORANDUM OF DECISION ON TRUSTEE’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT The plaintiff in this adversary proceeding and the chapter 7 trustee in the main case, Joseph H. Baldiga, has moved for summary judgment on a complaint against defendants C.A. Acquisition Corp. (“C.A. Acquisition”), C.A. Acquisition Newco, LLC (“Newco”), and Paycash Mobile, LLC (“Paycash). The trustee’s claims against the defendants arise primarily from their alleged failure to comply with the terms of an agreement to purchase the assets of Cyphermint, Inc. (“Cyphermint”), the debtor in the main case. The defendants oppose the summary judgment motion. 1 Case 10-04054 Doc 69 Filed 07/25/13 Entered 07/25/13 15:27:53 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 13 Facts The relevant facts have been established by those allegations in the complaint admitted to by the defendants, the two affidavits and accompanying exhibits submitted by the trustee in support of his motion for summary judgment,1 and the facts in the trustee’s Concise Statement of Material Facts which have not been disputed by the defendants. On August 28, 2008, C.A. Acquisition offered to purchase the assets of the debtor. -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms.