California Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vintage 2009 Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon

VINTAGE 2009 NAPA VALLEY The Gallo Signature Series honors the journey the Gallo family started in 1933, and it celebrates how far the family has come. With some of California’s best grapes at her fingertips, third- CABERNET SAUVIGNON generation winemaker Gina Gallo, has created three distinct wines that could only be crafted from the Gallo family’s unique combination of vineyards. For Gina, the Gallo Signature Series VARIETAL CONTENT: expresses her family’s passion for great vineyards and great wine, and it reflects the best the Gallo 93% CABERNET SAUVIGNON, 7% PETIT VERDOT, Winery has to offer. The Gallo Signature Series marks a return to hands-on, artisanal APPELLATION: winemaking for Gina, and it brings to life the enduring legacy of Ernest and Julio Gallo. NAPA VALLEY: ABOUT NAPA VALLEY 85% WILLIAM HILL ESTATE VINEYARD ................................................................................................ SONOMA COUNTY: Flanked by soaring mountains on all sides, Napa Valley is a world-renowned wine region with an 15% MONTE ROSSO VINEYARD ideal climate for growing high quality grapes. From the deep, nutrient-rich soils of the valley BARRELS PRODUCED: 169 floor to the terraced vineyards of the rocky hillsides, from the windswept estuarine flats to the ALCOHOL LEVEL: 14.8% mountaintop vineyards, Napa’s 15 sub-appellations share a common thread: warm days and cool RESIDUAL SUGAR: 0.05 G/100ML nights. TITRATABLE ACIDITY: 0.62 G/100ML PH: 3.65 ABOUT WILLIAM HILL ESTATE VINEYARD ................................................................................................ Most of the grapes in our Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon come from our acclaimed William Hill Estate vineyard in Southern Napa. Set above the valley floor at varying elevations, this vineyard sees diverse microclimates and basks in abundant sunlight, thanks to its southwestern exposure. -

A Wine Dynasty Comes to New Hampshire

Complimentary Copy JANAURY 2019 | LiquorandWineOutlets.com Great Selection. Great Prices. NO Taxes. Gina Gallo & Jean-Charles Boisset Powerhouse Wine Couple Brings Their Wine Dynasty to NH Wine Week Bourbon Heritage Alive and Well at Buffalo Trace Après Ski in Style with 5 Great Recipes Culinary Excellence Found at Thompson House Eatery H 15% OFF JOIN US FOR CUSTOMER APPRECIATION WINE WEEK WINE SALE Details on page 5 DETAILS ON PAGE 4 H H H H J ANUARY 2019 H H H Contents LiquorandWineOutlets.com 14 18 22 24 8 CELEBRATE SPIRITS CELEBRATE WINE CELEBRATE GOOD TASTE 6 ON OUR SHELVES 12 THE WINE CONNOISSEUR 18 THE RESTAURATEUR What’s new in spirits at our stores What’s a nice glass of red wine? Quality of life, culinary excellence meet at Thompson House Eatery in Jackson 8 THE DISTILLER’S CRAFT 13 THE ENTHUSIAST Bourbon heritage and progress meet 22 LOCAL FLAVOR 14 WORLD OF WINE at Buffalo Trace Doire Distilling pairs spirits, community Gina Gallo and Jean-Charles pride in downtown Derry 27 SPIRITS BUYER’S GUIDE Boisset bring their wine dynasty Price list of products by category to New Hampshire 24 LET’S ENTERTAIN Elevate your après ski with these 47 WINE BUYER’S GUIDE recipes Wine price list by location and category 4 LETTERS FROM THE ON THE COVER: Gina Gallo, senior director of winemaking at E&J Gallo Winery and GOVERNOR AND CHAIRMAN Jean-Charles Boisset, proprietor of the Boisset Collection, which operates 25 wineries in 20 INSIDE THE OUTLET California, France and Canada. North Country customers enjoy YOU CAN READ CELEBRATE NH ONLINE! Just go to LiquorandWineOutlets.com upgrades at Lancaster Outlet and click on the cover icon under Learn & Entertain/Celebrate NH Magazine. -

June 10, 2015 Northwest Office Building, Conference Room 117, Harrisburg, Pa

PENNSYLVANIA LIQUOR CONTROL BOARD MEETING MINUTES WEDNESDAY, JUNE 10, 2015 NORTHWEST OFFICE BUILDING, CONFERENCE ROOM 117, HARRISBURG, PA Tim Holden, Chairman Office of Chief Counsel Bureau of Retail Operations Joseph E. “Skip” Brion, Board Member Bureau of Licensing Bureau of Product Selection/Marketing Michael Negra, Board Member Bureau of Human Resources Financial Report John E. Metzger, Executive Director Bureau of Purchasing and Contracting Other Issues John Stark, Board Secretary PUBLIC MEETING – 11:00 A.M Board Secretary John K. Stark indicated that a quorum of the Board was present and Chairman Holden called the meeting to order. CALL TO ORDER ...................................................................................................................... Chairman Holden Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag OLD BUSINESS ................................................................................................................................ Secretary Stark A. Motion to approve the previous Board Meeting Minutes of the May 13, 2015 meeting. Motion Made: Board Member Negra Seconded: Board Member Brion Board Decision: Unanimously approved (3-0 vote) previous Board Minutes. PUBLIC COMMENT ON AGENDA ITEMS There was no comment on the printed agenda items. NEW BUSINESS From the Office of Chief Counsel ....................................................................... Faith Smith Diehl, Chief Counsel (1) BCLT, INC. Petition for Allowance of Appeal to 1400 Fifth Avenue Supreme Court Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219-6216 Restaurant Liquor License No. R-10019 LID 49876 Docket No. 1380 C.D. 2014 (Commonwealth Court) Note: Board Minutes are not officially approved until all required signatures are affixed. Motion Made: Board Member Negra Seconded: Board Member Brion Board Decision: Unanimously agreed (3-0 vote) – Do Not Pursue Petition. (2) BBRM 141 SECOND STREET, LLC Appeal to Commonwealth Court t/a McMonagle’s & Pizza Joe 6 Packs 153 Union Street California, PA 15419 Restaurant Liquor License No. -

Ultimate Wine Challenge 2016 Full Results

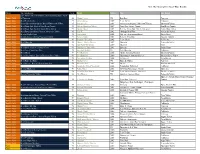

Ultimate Wine Challenge 2016 Full Results Awards: CT: Chairman's Trophy F: Finalist GV: Great Value T&T: Tried & True Award. All products are 750ml unless otherwise noted. Type Subtype Score Product Name Country Price Awards Champagne/Sparkling Wines Asti/Moscato d’Asti – Italy 94 Tosti 2015 Moscato Italy €13.00 CT d'Asti, 5.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Asti/Moscato d’Asti – Italy 92 Cupcake Vineyards Italy $14.99 F | GV 2015 Moscato d'Asti, 5.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Cava – Spain 93 Can Petit Rose Cava Spain $20.00 CT | GV 2013 Penedes, 11.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Cava – Spain 92 Celler Barcelona Brut Spain $18.00 F | GV NV Cava, 11.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Cava – Spain 89 Can Petit Brut Cava Spain $20.00 2013 Penedes, 11.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Cava – Spain 89 Cavas Hill Brut 1887 NV Spain $13.00 GV Cava, 11.9% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Champagne - France 95 Moet & Chandon Grand France $65.00 CT | T&T Vintage 2006 Epernay, 12.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Champagne - France 93 Beaumont des Crayeres France $39.99 F | GV Grande Reserve NV Epernay, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Champagne - France 93 Moet & Chandon France $50.00 F | T&T Imperial Rose NV Epernay, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Champagne - France 93 Moet & Chandon Grand France $69.99 F | T&T Vintage Rose 2008 Epernay, 12.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Champagne - France 92 Moet & Chandon France $41.00 F | GV | T&T Imperial Brut NV Epernay, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling Wines Prosecco - Italy 96 Mionetto Prestige Italy $14.00 -

Ultimate Wine Challenge 2017 Award Winners

Ultimate Wine Challenge 2017 Award Winners Type Subtype Score Product Name Country Price Awards Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Asti/Moscato d’Asti—Italy 92 Cinzano Asti Italy $11.99 GV Wines Moscato Asti, 7% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Asti/Moscato d’Asti—Italy 90 Martini & Rossi Italy $11.00 GV Wines Asti, 7.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Cava—Spain 95 MM Gran Spain $29.99 CT Wines Reserva Brut Nature 2012 Cava, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Cava—Spain 93 Anna de Spain $15.00 F | GV Wines Codorniu Anna Brut Rose Cava, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Cava—Spain 93 Poema Brut Spain $12.99 F | GV Wines Cava Penedes, 11.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Cava—Spain 93 Poema Brut Spain $12.99 F | GV Wines Rosado Cava Catalonia, 11.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Champagne—France 95 Moet & France $64.99 CT Wines Chandon Brut Grand Vintage 2008 Epernay, 12.5% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Champagne—France 92 Moet & France $39.99 F | T&T Wines Chandon Imperial Brut Epernay, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Champagne—France 93 Moet & France $49.99 F | T&T Wines Chandon Imperial Brut Rose Epernay, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Champagne—France 92 Cloutier France $39.99 F Wines Champagne Cuvee Grande Reserve Brut La Marne, 12% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Frizzante Wines—World 97 Cantine Aurora Italy $16.99 CT | GV Wines Dolce Stilnovo Rosso Piedmont, 7% abv Champagne/Sparkling/Frizzante Frizzante Wines—World 92 Medici Ermete Italy $13.99 F | GV Wines i Quercioli Secco Reggiano Lambrusco, 11% -

2018 the Toast of the Coast Wine Results

2018 The Toast of the Coast Wine Results Medal Special Awards Score Brand Vintage Wine Appellation THE TOAST OF THE COAST, Best Sparkling Rose, Best Double Gold of Carneros 96 Gloria Ferrer NV Brut Rosé Carneros Double Gold Best Petite Sirah 95 Vino Urbano 2015 Petite Sirah California Double Gold Best Cabernet Sauvignon, Best of Dry Creek Valley 95 Pedroncelli 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon, Block 007 Estate Dry Creek Valley Double Gold Best Pinot Gris, Best of San Diego County 95 Volcan Mountain Winery 2017 Pinot Gris, Estate Grown San Diego County Double Gold Best Pinot Noir, Best of Santa Maria Valley 95 Double Bond 2013 Reserve Pinot Noir, Toretti Vineyard Santa Maria Valley Double Gold Best Bordeaux Blend, Best of Alexander Valley 95 Cult X 2012 Meritage Red Wine Alexander Valley Double Gold Best of North Coast 95 Costa Azul 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon/Shiraz North Coast Double Gold Best Zinfandel, Best of Amador County 95 Sobon Estate 2015 ReZerve Primitivo Amador County Double Gold 94 Stanton Vineyards 2015 Petite Sirah St. Helena Double Gold Best Moscato 94 Maurice Car'rie Winery 2017 Moscato Temecula Valley Double Gold 94 Oak Farm Vineyards 2017 Albarino Lodi Double Gold Best Barbera, Best of South Coast 94 Old Survey Vineyards 2015 Barbera South Coast Double Gold Best Sweet Sparkling Wine 94 Barefoot Bubbly NV Pink Moscato California Double Gold Best Merlot 94 Frei Brothers 2015 Merlot, Sonoma Reserve Dry Creek Valley Double Gold Best Chardonnay, Best of Russian River Valley 94 Frei Brothers 2016 Chardonnay, Sonoma Reserve Russian River -

REVUE DE PRESSE 21/02/2018 Sommaire

REVUE DE PRESSE 21/02/2018 Sommaire The Rhône is a little more complicated than Villages level and Châteauneuf-du-Pape 3 belfastlive.co.uk - 10/02/2018 The Rhone holds a special place in my wine cellar 5 The News (UK) Porstmouth - Porstmouth - 03/02/2018 ALISTAIR GIBSON: The Rhone holds a special place in my wine cellar 6 portsmouth.co.uk - 02/02/2018 Secrets Waiting to be Uncovered 8 riddlemagazine.com - 24/01/2018 WINE 10 Stockport Express - 17/01/2018 RAISE A GLASS 11 Manchester Evening News - 13/01/2018 Paula’s Wines of the Week starting 8th January 2018 12 Maturetimes.co.uk - 08/01/2018 WINE 13 Rossendale Free Press - 22/12/2017 WINE 14 Accrington Observer - 22/12/2017 WINE 15 Heywood Advertiser - 21/12/2017 WINE 16 Middleton Guardian - 21/12/2017 WINE 17 Rochdale Observer - 20/12/2017 WINE 18 Macclesfield Express - 20/12/2017 WINE 19 Stockport Express - 20/12/2017 BD TRAVEL FEATURE: HELLO SWEETIE….AND ENJOY YOUR VISIT TO SOUTHERN FRANCE! 20 belfastdaily.co.uk - 09/12/2017 Hello Sweetie! 22 ein.org - 08/12/2017 Ravishing red Rhône: some first impressions of the new 2016 vintage 25 the-buyer.net - 23/11/2017 When in Rhone... enjoy great food and wine in the beautiful south of France 27 oxfordmail.co.uk - 02/11/2017 P.2 URL :http://www.belfastlive.co.uk belfastlive.co.uk PAYS :Royaume-uni TYPE :Web International 10 février 2018 - 12:59 > Version en ligne The Rhône is a little more complicated than Villages level and Châteauneuf-du-Pape Get daily updates directly to your inbox + Subscribe Thank you for subscribing! Could not subscribe, try again later Invalid Email Everybody knows the Rhône, with its wee hat over the ‘O’ and chunky reds you want to drink with a dish that involves a cheap cut of meat, lots of herbs and half a day in a low oven. -

Kĵŝöǐmƪĵöǐ3ŭǵƪŝzō

kĴŝÖǐMƪĴÖǐ3ŭǵƪŝzō 0QXGODGT 2017 Your Exclusive Distributor of Riedel, the Wine Glass Company 100 Enterprise Avenue Target Industrial Circle Gardiner, Maine 04345 Bangor, Maine 04401 1-800-452-4633 PSB TER BRAND TYPE SIZE APPELLATION VTG F-LINE POST NOV CASE SSP UPC CODE CODE BTL OFF COST PRICE NEW ITEMS DOMESTIC 187277 APOTHIC INFERNO 750 ML CALIFORNIA $12.31 $1.54 $10.77 $13.99 0 85000 02490 886014 DOMINANT 7 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 750 ML CALIFORNIA $5.77 $0.00 $5.77 $7.99 8 94509 00866 886010 DOMINANT 7 CHARDONNAY 750 ML CALIFORNIA $5.77 $0.00 $5.77 $7.99 8 94509 00864 886012 DOMINANT 7 RED BLEND 750 ML CALIFORNIA $5.77 $0.00 $5.77 $7.99 8 94509 00862 818145 GALLO FAMILY VINEYARDS SWEET APPLE 750 ML CALIFORNIA $3.46 $0.00 $3.46 $4.49 0 85000 02557 818147 GALLO FAMILY VINEYARDS SWEET BERRY 750 ML CALIFORNIA $3.46 $0.00 $3.46 $4.49 0 85000 02298 818148 GALLO FAMILY VINEYARDS SWEET BERRY 1.5 L CALIFORNIA $7.69 $0.77 $6.92 $8.99 0 85000 02559 818146 GALLO FAMILY VINEYARDS SWEET PEACH 750 ML CALIFORNIA $3.46 $0.00 $3.46 $4.49 0 85000 02257 818144 GALLO FAMILY VINEYARDS SWEET PINEAPPLE 750 ML CALIFORNIA $3.46 $0.00 $3.46 $4.49 0 85000 02256 213716 HONIG CABERNET SAUVIGNON 3.0 L NAPA VALLEY $169.00 $0.00 $169.00 $219.00 9 99999 99999 212718 HONIG CABERNET SAUVIGNON 1.5 L NAPA VALLEY $390.00 $0.00 $390.00 $99.99 9 99999 99999 130222 KUNDE ESTATE CHARDONNAY 750 ML SONOMA $9.23 $0.00 $9.23 $11.99 9 99999 99999 128919 ORIN SWIFT BLANK STARE SAUVIGNON BLANC 750 ML RUSSIAN RIVER $24.50 $0.00 $24.50 $282.00 $34.99 0 85000 02636 164793 QUEENS PEAK CABERNET -

Success of Family Company: Critical Evidence from the United States

TRENDY EKONOMIKY A MANAGEMENTU TRENDS ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT ISSN 1802-8527 (Print) / ISSN 2336-6508 (Online) 2016 27(3): 57–66 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13164/trends.2016.27.57 Success of Family Company: Critical Evidence from the United States Anastasia Petlina Abstract Purpose of the article: The purpose of the paper is to define the point of family company’s success. The object of research is family business as an economical phenomenon. There is a double subject of this study: firstly, to find out the main resources, from which information about successful companies can be detected and, secondly, to analyze one big family company as case study for identification its key success factors. Methodology/methods: The article was prepared on the basis of general theoretical scientific methods, in particular analysis, synthesis, analogy, comparison, generalizations, deduction and methods of expert estimates. In the first phase secondary research of scientific literature and electronic resources about the paper topic was conducted. On the base of that result, the primary research was conduct, which is based on analysis of family company E. & J. Gallo Winery. Based on the received information, the key success factors were identified. The sources of the research are internet web-pages of the company, articles about company in famous Czech business magazines and scientific journals form Emerald database, reports of company and financial data from Amadeus database and The Global Family Business Index. Scientific aim: The aim of scientific research is to improve the understanding of family company’s success from the perspective of difficulties faced by family company. -

HLSR Rodeouncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results

HLSR RodeoUncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Grand Champion Best of Show, Marchesi Antinori Srl Guado al Tasso, Bolgheri DOC Superiore, 2009 Old World Bordeaux-Blend Red Double-Gold Italy Class Champion Reserve Grand Champion, Class Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards Estate Bottled Pinot Noir, Russian River New World Pinot Noir ($23-$35) Double-Gold U.S. Champion Valley, 2010 Top Texas, Class Champion, Bending Branch Winery Estate Grown Tannat, Texas Hill Country, 2011 Tannat Double-Gold Texas Texas Class Champion Top Chilean, Class Champion, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon ($16 and La Playa Vineyards Axel Cabernet Sauvignon, Colchagua Valley, 2011 Double-Gold Chile Chile Class Champion higher) Top Red, Class Champion Fess Parker Winery The Big Easy, Santa Barbara County, 2011 Other Rhone-Style Varietals/Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top White, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling, Finger Lakes, 2011 Riesling - Semi-Dry Double-Gold U.S. Top Sparkling, Class Champion Sophora Sparkling Rose, New Zealand, NV Sparkling Rose Double-Gold New Zealand Top Sweet, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling Ice Wine, Finger Lakes, 2010 Riesling-Sweet Double-Gold U.S. Top Value, Class Champion Vigilance Red Blend " Cimarron", Red Hills Lake County, 2011 Cab-Syrah/Syrah-Cab Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top Winery Michael David Winery Top Wine Outfit Trinchero Family Estates Top Chilean Wine Outfit Concha Y Toro AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region 10 Span Chardonnay, Central Coast, California, 2012 Chardonnay wooded ($10 -$12) Silver U.S. 10 Span Pinot Gris, Monterey, California, 2012 Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio ($11-$15) Silver U.S. -

TG Summer Journal 2015 1.Indd

SIZZLING CIDER AGING OUR TASTING SENSES DOUBLE GOLD TASTING NOTES BOXED WINE VS. BOTTLED WINE 11 Night West Indies Hideaway Jan. 27-Feb. 7, 2016 AZAMARA INCLUSIVE Tasters Guild Cruise Package! * All Gratuiti es Included! * Select standard spirits, an internati onal selecti on of beers plus bouti que red and white wines through- out the voyage-ALL INCLUDED! * Bott led water, soft drinks, specialty coff ees and teas. * One FREE AzAmazing Evening of entertainment * Private Tasters Guild Wine Tasti ng. * English-trained butler service for suite guests * Free shutt le to and from port communiti es, where available. * Concierge services for personal guidance and reservati ons. * Self-service laundry. * Only 694 passengers aboard Azamara Journey. From pristi ne beaches and waterfalls to simple small towns and elegant resorts, this voyage has adventures for every taste. You'll love the small French fi shing village of Terrede-Haut, with shops and restaurants within walking distance of your ship. Hike to water- falls and rainforests on lush Roseau, and tour old plantati on homes and botanical gardens on friendly Nevis. Sophisti cated St. Barts caters to Jet-set tastes with elegant shops, fi ne dining and gorgeous beaches. The next day you can swim among the giant volcanic boulders at the Baths at Virgin Gorda. And you'll love this ship - Guaranteed! Over half of the Tasters Guild people on our cruise to South America last January have already booked their cabin for this Great Caribbean cruise to the West In- dies. STATEROOMS FROM $3,249 11 NIGHTS - WEST INDIES HIDEAWAY TUE 27-Jan Miami, Florida WED 28-Jan At Sea Cruising THU 29-Jan At Sea Cruising FRI 30-Jan St. -

HLSR Rodeouncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results

HLSR RodeoUncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Grand Champion Best of Show, Marchesi Antinori Srl Guado al Tasso, Bolgheri DOC Superiore, 2009 Old World Bordeaux-Blend Red Double-Gold Italy Class Champion Reserve Grand Champion, Class Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards Estate Bottled Pinot Noir, Russian River New World Pinot Noir ($23-$35) Double-Gold U.S. Champion Valley, 2010 Top Texas, Class Champion, Bending Branch Winery Estate Grown Tannat, Texas Hill Country, 2011 Tannat Double-Gold Texas Texas Class Champion Top Chilean, Class Champion, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon ($16 and La Playa Vineyards Axel Cabernet Sauvignon, Colchagua Valley, 2011 Double-Gold Chile Chile Class Champion higher) Top Red, Class Champion Fess Parker Winery The Big Easy, Santa Barbara County, 2011 Other Rhone-Style Varietals/Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top White, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling, Finger Lakes, 2011 Riesling - Semi-Dry Double-Gold U.S. Top Sparkling, Class Champion Sophora Sparkling Rose, New Zealand, NV Sparkling Rose Double-Gold New Zealand Top Sweet, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling Ice Wine, Finger Lakes, 2010 Riesling-Sweet Double-Gold U.S. Top Value, Class Champion Vigilance Red Blend " Cimarron", Red Hills Lake County, 2011 Cab-Syrah/Syrah-Cab Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top Winery Michael David Winery Top Wine Outfit Trinchero Family Estates Top Chilean Wine Outfit Concha Y Toro AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Class Champion Tikal Natural Red Blend, Mendoza, 2011 Argentinean Red Blends Double-Gold Argentina Class Champion Terra d'Oro Winery Barbera, Amador County, 2011 Barbera Double-Gold U.S. Class Champion Inkblot Cabernet Franc, Lodi, 2010 Cabernet Franc Double-Gold U.S.