Midrash and Midrashic Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S

February 5 — 11, 2021 23 — 29 Shevat 5781 Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● www.torahohrboca.org ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S. Yasgur President, Jonas Waizer Office Hours Monday - Thursday 9:00am - 3:00pm, Friday 9:00am - 12noon WEEKDAY TIMES Earliest Davening (Fri-Thurs) 5:53am* Mishna Yomit (in Shul & online) 15 min. before Mincha Earliest Tallit/Tefillin (Fri-Thurs) 6:20am* Mincha/Ma’ariv (Shul & Tent) (S-Th) Shacharit at Shul (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 7:30am Shacharit in the Tent (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 8:30am Daven Mincha (S-Th) prior to 6:08pm Daf Yomi (online) 8:30am Repeat Kriat Shema after 6:46pm* Chumash Class (online) 9:30am *These are the latest times during the week BS”D CONGREGATION TORAH OHR NEW - UPDATED POLICIES FOR KEEPING OUR COMMUNITY SAFE We enjoy the seasonal return of our cherished congregants, friends, and neighbors. At the same time, let us acknowledge that the Corona-19 pandemic is not yet over. We cannot afford complacency in our sheltered senior community until the pandemic is fully controlled. Considering the situation of pikuach nefesh, the Shul will continue policies that protect all our members. We want you in Shul ASAP. But first, individuals returning to Florida, even from short out-of-state stays, must adhere to the CDC, Florida State and Shul rules: a) Self-isolate for 12 days; DO NOT ATTEND SHUL, including outdoor minyanim. If you have no symptoms after 12 days, please SHABBAT YITRO register to attend shul minyanim. -

Foreword, Abbreviations, Glossary

FOREWORD, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY The Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5771 1 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY Halakhah.com Presents the Contents of the Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES, GLOSSARY AND INDICES UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R AB B I D R . I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. FOREWORD BY THE VERY REV. THE LATE CHIEF RABBI DR. J. H. HERTZ INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR THE SONCINO PRESS LONDON Original footnotes renumbered. 2 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY These are the Sedarim ("orders", or major There are about 12,800 printed pages in the divisions) and tractates (books) of the Soncino Talmud, not counting introductions, Babylonian Talmud, as translated and indexes, glossaries, etc. Of these, this site has organized for publication by the Soncino about 8050 pages on line, comprising about Press in 1935 - 1948. 1460 files — about 63% of the Soncino Talmud. This should in no way be considered The English terms in italics are taken from a substitute for the printed edition, with the the Introductions in the respective Soncino complete text, fully cross-referenced volumes. A summary of the contents of each footnotes, a master index, an index for each Tractate is given in the Introduction to the tractate, scriptural index, rabbinical index, Seder, and a detailed summary by chapter is and so on. given in the Introduction to the Tractate. SEDER ZERA‘IM (Seeds : 11 tractates) Introduction to Seder Zera‘im — Rabbi Dr. I Epstein INDEX Foreword — The Very Rev. The Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie Abbreviations Glossary 1. -

4 / Midrash and History: a Key to the Babelesque Imagination

4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination Myth as History Myth in Babelʹ’s fiction gives an illusion of the epic while mocking it, and reads unorthodox interpretations and essential truths into history. For Babelʹ, the myths of history and religion were a subtle medium for allegorical parallels, as well as ironic allusions to a moral message. This is an essentially midrashic approach to history, fol- lowing the ancient Jewish storytelling tradition that imaginatively elaborates on biblical and historical narrative, usually for exegetic or homiletic purposes, and playfully draws on intertextual, ver- bal, and semantic associations. Often new, contemporary meaning is introduced into the reading of familiar stories, or biblical ver- ses are given unexpected levels of meaning that dramatizes bib- lical figures as human. As Daniel Boyarin has demonstrated, midrash, the biblical metacommentary that forms part of Tal- mudic lore, is fundamentally intertextual and sets up a coded dua- lity between the exegetical text and the quoted or referenced pas- sage. When a textual moment is felt to be awkward, what Michel Rifattere terms “ungrammaticality” points to gaps that provide the key to decoding through another text.1 The midrashic mode informs the Jewish imagination at times of cultural repression (such as under the Romans or the Tsars), and characterizes the way the canon of Jewish literature has developed and renewed itself. There is something we might call midrashic in Babelʹ’s view of history. 129 4 / Midrash and History We may find a key to Babelʹ’s midrashic view of history in the art of the Polish painter in Red Cavalry. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hanne Trautner-Kromann n this introduction I want to give the necessary background information for understanding the nine articles in this volume. II start with some comments on the Hebrew or Jewish Bible and the literature of the rabbis, based on the Bible, and then present the articles and the background information for these articles. In Jewish tradition the Bible consists of three main parts: 1. Torah – Teaching: The Five Books of Moses: Genesis (Bereshit in Hebrew), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vajikra), Numbers (Bemidbar), Deuteronomy (Devarim); 2. Nevi’im – Prophets: (The Former Prophets:) Joshua, Judges, Samuel I–II, Kings I–II; (The Latter Prophets:) Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezek- iel; (The Twelve Small Prophets:) Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephania, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; 3. Khetuvim – Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles I–II1. The Hebrew Bible is often called Tanakh after these three main parts: Torah, Nevi’im and Khetuvim. The Hebrew Bible has been interpreted and reinterpreted by rab- bis and scholars up through the ages – and still is2. Already in the Bible itself there are examples of interpretation (midrash). The books of Chronicles, for example, can be seen as a kind of midrash on the 10 | From Bible to Midrash books of Samuel and Kings, repeating but also changing many tradi- tions found in these books. In talmudic times,3 dating from the 1st to the 6th century C.E.(Common Era), the rabbis developed and refined the systems of interpretation which can be found in their literature, often referred to as The Writings of the Sages. -

The Anti-Samaritan Attitude As Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim

religions Article The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim Andreas Lehnardt Faculty of Protestant Theology, Johannes Gutenberg‑University Mainz, 55122 Mainz, Germany; lehnardt@uni‑mainz.de Abstract: Samaritans, as a group within the ranges of ancient ‘Judaisms’, are often mentioned in Talmud and Midrash. As comparable social–religious entities, they are regarded ambivalently by the rabbis. First, they were viewed as Jews, but from the end of the Tannaitic times, and especially after the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were perceived as non‑Jews, not reliable about different fields of Halakhic concern. Rabbinic writings reflect on this change in attitude and describe a long ongoing conflict and a growing anti‑Samaritan attitude. This article analyzes several dialogues betweenrab‑ bis and Samaritans transmitted in the Midrash on the book of Genesis, Bereshit Rabbah. In four larger sections, the famous Rabbi Me’ir is depicted as the counterpart of certain Samaritans. The analyses of these discussions try to show how rabbinic texts avoid any direct exegetical dispute over particular verses of the Torah, but point to other hermeneutical levels of discourse and the rejection of Samari‑ tan claims. These texts thus reflect a remarkable understanding of some Samaritan convictions, and they demonstrate how rabbis denounced Samaritanism and refuted their counterparts. The Rabbi Me’ir dialogues thus are an impressive literary witness to the final stages of the parting of ways of these diverging religious streams. Keywords: Samaritans; ancient Judaism; rabbinic literature; Talmud; Midrash Citation: Lehnardt, Andreas. 2021. The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as 1 Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim. The attitudes towards the Samaritans (or Kutim ) documented in rabbinical literature 2 Religions 12: 584. -

Shavuot in Talmud and Midrash (Mostly Soncino Translation and Commentary; Emphasis Mine; Some Language Tweaks)

22 May 2007 [Shavuot 5767] Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Tikkun Lel Shavuot Shavuot in Talmud and Midrash (Mostly Soncino translation and commentary; emphasis mine; some language tweaks) Only Israel accepted the Torah Mechilta de Rabbi Ishmael, Exodus 20:2 It was for the following reason that the ancient nations of the world were asked to accept the Torah, in order that they should have no excuse for saying, 'Had we been asked we would have accepted it'. For, behold, they were asked and they refused to accept it, for it is said, "He said, the Lord came from Sinai...) (Deut. 33:2). He appeared to the children of Esau, the wicked, and said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not murder" (Deut. 5:17) They then said to Him, "The very heritage which our father left us was 'By the sword you shall live' (Gen. 27:40). He then appeared to the children of Ammon and Moab. He said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not commit adultery" (Deut. 5:17) They, however, said to Him that they were, all of them, the children of adulterers, as it is said, "Thus the two daughters of Lot came to be with child by their father" (Gen. 19:36) He then appeared to the children of Ishmael. He said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not steal" (Deut. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Organization of the Talmud

Organization of the Talmud Contents The Sections and Tracts of the Talmud ................................. 2 Seder Zeraim (Seeds) ............................................ 2 Seder Moed (Festivals) ........................................... 2 Seder Nashim (Women) .......................................... 2 Seder Nezikin (Damages) ......................................... 3 Seder Kodashim (Holy Things) ...................................... 3 Seder Toharot (Purity) ........................................... 3 The rabbis of the 2nd and 3rd centuries after Christ At a certain point, probably during the 2nd cen- organized the Talmud in the form we find it to- tury after Christ, the Pharisees gave permission for day. Rabbi Jehudah the Nasi (3rd Century, presi- writing the law. Until then it was absolutely forbid- dent of the Sanhedrin) began the work of gathering den to put the oral law in writing. No sooner had together all the notes, archives, and records from this been granted that the number of manuscripts which the Talmud would be compiled. The scholars began to be very great, and when Rabbi Jehudah in Spain asserted that these notes had been in ex- had been confirmed in authority (since he enjoyed istence since schools had begun in Israel, possibly the friendship of a Roman named Antonius, who from as early as Ezra’s time. was in power in Rome), he discovered that “from the multitude of the trees the forest could not be Other Jewish scholars of that period, notably those seen.” living in France, declared that not a line was writ- ten down anywhere until this compilation began, The period of the 3rd century was very favorable for and that the writing was done from memory alone, this undertaking, because the Talmud, and its Jew- the memory of the living rabbis who were the con- ish followers, enjoyed a rest from persecutors. -

URJ Online Communications Master Word List 1 MASTER

URJ Online Communications Master Word List MASTER WORD LIST, Ashamnu (prayer) REFORMJUDAISM.org Ashkenazi, Ashkenazim Revised 02-12-15 Ashkenazic Ashrei (prayer) Acharei Mot (parashah) atzei chayim acknowledgment atzeret Adar (month) aufruf Adar I (month) Av (month) Adar II (month) Avadim (tractate) “Adir Hu” (song) avanah Adon Olam aveirah Adonai Avinu Malkeinu (prayer) Adonai Melech Avinu shebashamayim Adonai Tz’vaot (the God of heaven’s hosts [Rev. avodah Plaut translation] Avodah Zarah (tractate) afikoman avon aggadah, aggadot Avot (tractate) aggadic Avot D’Rabbi Natan (tractate) agunah Avot V’Imahot (prayer) ahavah ayin (letter) Ahavah Rabbah (prayer) Ahavat Olam (prayer) baal korei Akeidah Baal Shem Tov Akiva baal t’shuvah Al Cheit (prayer) Babylonian Empire aleph (letter) Babylonian exile alef-bet Babylonian Talmud Aleinu (prayer) baby naming, baby-naming ceremony Al HaNisim (prayer) badchan aliyah, aliyot Balak (parashah) A.M. (SMALL CAPS) bal tashchit am baraita, baraitot Amidah Bar’chu Amora, Amoraim bareich amoraic Bar Kochba am s’gulah bar mitzvah Am Yisrael Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, Angel of Death asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu Ani Maamin (prayer) Baruch She-Amar (prayer) aninut Baruch Shem anti-Semitism Baruch SheNatan (prayer) Arachin (tractate) bashert, basherte aravah bat arbaah minim bat mitzvah arba kanfot Bava Batra (tractate) Arba Parashiyot Bava Kama (tractate) ark (synagogue) Bava M’tzia (tractate) ark (Noah’s) Bavli Ark of the Covenant, the Ark bayit (house) Aron HaB’rit Bayit (the Temple) -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship. WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA How to cite: WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA (2018) Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13052/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship Eris Kathlyn Laura Williams-Reed A thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History Durham University 2018 Acknowledgments It is a joy to recall the many people who, each in their own way, made this thesis possible. Firstly, I owe a great deal of thanks to my supervisor, Ted Kaizer, for his support and encouragement throughout my doctorate, as well as my undergraduate and postgraduate studies. -

Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

The Child at the Edge of the Cemetery: Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot MARTIN S. COHEN j i f the Mishnah wears seven veils so as modestly to hide its inmost charms from all but the most worthy of its admirers, then its sixth sec- I tion, Seder Tohorot, wears seventy of them. But to merit a peek behind those many veils requires more than the ardor or determination of even the most persistent suitor. Indeed, there is no more daunting section of the rab- binic corpus to understand—or more challenging to enjoy or more formidable to analyze . or more demoralizing to the student whose a pri- ori assumption is that the texts of classical Judaism were meant, above all, to inspire spiritual growth through their devotional study. It is no coincidence that it is rarely, if ever, studied in much depth. Indeed, other than for Tractate Niddah (which deals mostly with the laws concerning the purity status of menstruant women and the men who come into casual or intimate contact with them), there is no Talmud for any trac- tate in the seder, which detail can be interpreted to suggest that even the amoraim themselves found the material more than just slightly daunting.1 Cast in the language of science, yet clearly not founded on the kind of scien- tific principles “real” scientists bring to the informed inspection and analysis of the physical universe, the laws put forward in the sixth seder of the Mish- nah appear—at least at first blush—to have a certain dreamy arbitrariness about them able to make even the most assiduous reader despair of finding much fodder for contemplative analysis. -

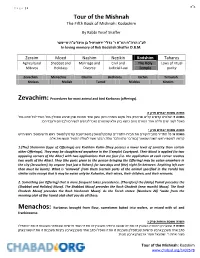

Tour of the Mishnah the Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim

ב"ה P a g e | 1 Tour of the Mishnah The Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim By Rabbi Yosef Shaffer לע"נ הרה"ח הוו"ח ר' גדלי' ירחמיא-ל בן מיכל ע"ה שייפער In loving memory of Reb Gedaliah Shaffer O.B.M. Zeraim Moed Nashim Nezikin Kodshim Taharos Agricultural Shabbat and Marriage and Civil and The Holy Laws of ritual Mitzvos Holidays Divorce Judicial Law Temple purity Zevachim Menachos Chullin Bechoros Erchin Temurah Kreisos Meilah Tamid Middos Kinnim Zevachim: Procedures for most animal and bird Korbanos (offerings). משנה מסכת זבחים פרק ה משנה ז: שלמים קדשים קלים שחיטתן בכל מקום בעזרה ודמן טעון שתי מתנות שהן ארבע ונאכלין בכל העיר לכל אדם בכל מאכל לשני ימים ולילה אחד המורם מהם כיוצא בהן אלא שהמורם נאכל לכהנים לנשיהם ולבניהם ולעבדיהם: משנה מסכת זבחים פרק י משנה א: כל התדיר מחבירו קודם את חבירו התמידים קודמין למוספין מוספי שבת קודמין למוספי ראש חדש מוספי ראש חדש קודמין למוספי ראש השנה שנאמר )במדבר כח( מלבד עולת הבקר אשר לעולת התמיד תעשו את אלה: 1.(The) Shelamim (type of Offerings) are Kodshim Kalim (they possess a lower level of sanctity than certain other Offerings). They may be slaughtered anywhere in the (Temple) Courtyard. Their blood is applied (to two opposing corners of the Altar) with two applications that are four (i.e. the application at each corner reaches two walls of the Altar). They (the parts given to the person bringing the Offering) may be eaten anywhere in the city (Jerusalem), by anyone (not just a Kohen), for two days and (the) night (in between.