My Completion of the Finale to Anton Bruckner's 9Th Symphony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol. 20, No. 3 The Organization of Canadian Symphony Musicians (ocsm)isthe voice of Canadian professional orchestral musicians. ocsm’s mission is to uphold and improve the working conditions of professional Canadian orchestral musicians, to promote commu- nication among its members, and to advocate on behalf of the Canadian cultural community. Editorial Vancouver dispute leads to By Barbara Hankins new rights for symphonic Editor extra musicians Does it matter to music lovers how the orchestra By Matt Heller looks? Many will say that people see us before they ocsm President hear us, and that ‘‘visual cohesion’’ is of paramount importance. Others say that a change of dress code In recent years, Vancouver Symphony musicians have from the stuffy tails and white tie is needed to break toured China, opened a new School of Music, and won down the barrier between the orchestra and audience. aGrammy Award. Atthe negotiating table, vso musi- Arlene Dahl’s article gives a clear overview of the cians have fought to keep pace with the city’s booming choices musicians and managements are considering. economy and to recover from a 25 per cent salary cut If you have an opinion on this, feel free to chime in on in 2000. The Vancouver Symphony’s last agreement the ocsm list or send me your thoughts for possible finished with the 2011–12 season, so negotiations use in the next Una Voce. should have begun last spring. What happened instead My personal view is was a contentious and complex dispute between the that while the dress vso Musicians Association (vsoma), and the Vancou- code should reflect our ver Musicians Association (vma), the afm Local repre- respect for our art and senting all unionized Vancouver musicians, including the tone of the concert, those in the vso. -

2017–18 Season Week 8 Beethoven Bruckner

2017–18 season andris nelsons music director week 8 beethoven bruckner Season Sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus supporting sponsorlead sponsor supporting sponsorlead thomas adès artistic partner Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to care and cure, but our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited future of healthcare. www.takeda.com Takeda is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra Table of Contents | Week 8 7 bso news 1 7 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 2 0 the boston symphony orchestra 23 parallel paths in early 20th-century music by jean-pascal vachon 3 2 this week’s program Notes on the Program 34 The Program in Brief… 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 43 Anton Bruckner 53 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 57 Rudolf Buchbinder 60 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on november 24 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2017 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

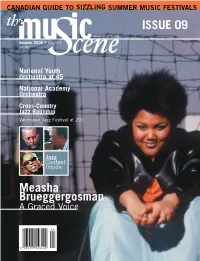

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting. -

The Symphonies of Anton Bruckner Revisited (2020) by John Quinn and Patrick Waller

The Symphonies of Anton Bruckner Revisited (2020) by John Quinn and Patrick Waller Introduction In 2005 we published a selective survey of recordings of the symphonies of Anton Bruckner. The survey was updated in 2009 but since then, though both of us have continued to listen frequently to the composer’s music, other commitments have prevented us from updating it. In April 2020 a reader who had consulted the survey contacted JQ to enquire whether the absence of many references to the cycle conducted by Simone Young implied disapproval. In fact, the reason that Ms Young’s recordings did not feature in our 2009 update was that up to that point neither of us had heard much of her work – most of the performances were issued later. However, the enquiry has prompted us to put together an update of the survey. We have reviewed the original text and we feel that most of our judgements on the individual recordings considered in 2005 and 2009 still apply. Readers can find the updated survey of 2009 here. Our joint recommendations in the previous article may be summarised as follows: • Symphony No. 00 Tintner (1998) • Symphony No. 0 Tintner (1996) • Symphony No. 1 Haitink (1972) • Symphony No. 2 Giulini (1974) • Symphony No. 3 Haitink (1988) • Symphony No. 4 Böhm (1973), Wand (1998) • Symphony No. 5 Horenstein (1971), Sinopoli (1999) • Symphony No. 6 Klemperer (1964), Haitink (2003) • Symphony No. 7 Wand (1999), Haitink (2007) • Symphony No. 8 Karajan (1988), Wand (2001) • Symphony No. 9 Walter (1959), Wand (1998) These choices merely represented what we believed to be the finest recorded performances we had yet heard; sound quality was not taken into account. -

Who Wrote Bruckner's 8Th Symphony…?

ISSN 1759-1201 www.brucknerjournal.co.uk Issued three times a year and sold by subscription FOUNDING EDITOR: Peter Palmer (1997-2004) Editor: Ken Ward [email protected] 23 Mornington Grove, London E3 4NS Subscriptions and Mailing: Raymond Cox [email protected] 4 Lulworth Close, Halesowen, B63 2UJ 01384 566383 VOLUME EIGHTEEN, NUMBER THREE, NOVEMBER 2014 Associate Editors Dr Crawford Howie & Dr Dermot Gault In this issue: The Ninth Bruckner Journal Who wrote Bruckner’s 8th symphony…? Readers Biennial Conference A RECENT comment on a concert review web-site was anxious to announcement page 2 assert that the cymbal clash in the 7th symphony “probably” did not Bad Kreuzen - Speculation originate with Bruckner and was not approved of by him. On the basis and no end - by Dr. Eva Marx Page 3 of the inconclusive evidence we have, there is no probability: we just Anton Bruckner’s early stays in do not know. Steyr - by Dr Erich W Partsch Page 10 In the case of the 8th symphony, we are sure that Bruckner alone Book Reviews: wrote the first version of 1887. If one is after ‘pure’ Bruckner in this Paul Hawkshaw: Critical Report symphony, this is the only place to find it. Come the 1890 version, we for Symphony VIII review by Dr. Dermot Gault Page 13 know its very existence was due to Hermann Levi’s rejection of the first version, that to some extent Bruckner involved Josef and Franz David Chapman Bruckner and The Generalbass Tradition Schalk in its extensive revision and re-composition, and that the review by Dr. -

R13970 Photograph Collection of the Music Division

R13970_Photograph Collection of the Music Division Accession Negative Subject Content Physical Date Photographer 823 Abramson, Ronney Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 21 x 26 ca. 1970s 428 Acklund, Jeanne Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 9 x 7 ca. 1950 824 Adams, Bryan Portrait, with guitar photo: b&w / n&b; 25 x 21 ca. 1980s 1755 Adams, Bryan Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 21 x 26 ca. 1990s Catlin, Andrew 1810 Adams, Bryan Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 26 x 21 ca. 1990s Catlin, Andrew Frances and Harry Adaskin in CBC-TV "To play like an photo: b&w / n&b; 21 x 26 Adaskin, Frances angel" on Spectrum, 7 (composite print of two 1 Marr|Adaskin, Harry November 1979. portraits 16 x 12) 1979 L 1936 Adaskin, John Portrait contact card ca. 1940s photo: b&w / n&b; 13 119 NL 14550 Adaskin, Murray Composing at the piano x13|contact card ca 1978 405 Adaskin, Murray Portrait photo: col. / coul.; 11 x 13 819 Adeney, Marcus Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 18 x 13 ca 1940s Roy, Marcel 825 Adeney, Marcus Portrait with cello photo: b&w / n&b; 26 x 21 ca 1945 Roy, Marcel Eleanor Agnew and Margaret Agnew, Eleanor|Wilson, Wilson in performance on 368 Margaret violin. photo: b&w / n&b; 18 x 25 335 Wilson, Margaret Portrait with violin L 1935 Agostini, Lucio Portrait contact card 1946 826 Agostini, Lucio In rehearsal photo: b&w / n&b; 20 x 25 820 Aide, William Portrait photo: b&w / n&b; 21 x 13 1985 Robert Aitken with the Accordes String Quartet in Aitken, Robert|Boulez, rehearsal with Pierre Boulez Pierre|Berard, for New Music Concerts, Marie|Accordes String Mississauga, Ont., 1991. -

School of Music 2013–2014

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2013–2014 School of Music 2013–2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 8 July 25, 2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 8 July 25, 2013 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers D-H BENJAMIN DALE (1885-1943) Born in London. An accomplished organist siince childhood, he entered the Royal Academy of Music at age 15 where he studied composition under Frederick Corder. He had early success as a composer and teacher including an appointment as Professor of Harmony at the Royal Academy of Music. He composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works, including a Concertstück (Concert Piece) for Organ and Orchestra (1904). Romance for Viola and Orchestra (from Suite, Op.2) (1906, orch. 1910) Sarah-Jane Bradley (viola)/Stephen Bell/The Hallé ( + Clarke: Viola Concerto, Walthew: A Mosaic in Ten Pieces and Warner: Suite in D minor) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX7329 (2016) SIR JOHN DANKWORTH (1927-2010) Born in Woodford, Essex into a musical family. He had learned to play various instruments bedore attending London's Royal Academy of Music. He became world famous as a jazz composer, saxophonist and clarinetist, and writer of film scores. He oten oerformed with his wife, the singer Cleo Laine. Clarinet Concerto "The Woolwich" Emma Johnson (clarinet)/Philip Ellis/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Reade: Suite From The Victorian Kitchen Garden, Todd: Clarinet Concerto and Hawes: Clarinet Concerto) NIMBUS ALLIANCE NI6328 (2016) CHRISTIAN DARNTON (1905-1981) Born in Leeds. His musical education was extensive including studies with Frederick Corder at the Brighton School of Music, Harold Craxton at the Matthay School, composition with Benjamin Dale and Harry Farjeon at Cambridge and Gordon Jacob at the Royal College of Music, private lessons with Charles MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos D-H Wood and Cyril Rootham and further studies with Max Butting in Germany. -

Download Booklet

557661-63 bk Berio US 3/13/06 11:21 AM Page 12 Also available: Luciano BERIO Sequenzas I-XIV for Solo Instruments Flute • Harp 8.559260 Soprano • Piano Trombone • Viola Oboe • Violin Clarinet • Trumpet Guitar • Bassoon Accordion • Cello Saxophones 8.559261 8.557661-63 12 3 CDs 557661-63 bk Berio US 3/13/06 11:21 AM Page 2 Luciano BERIO Also available: (1925-2003) Sequenzas I-XIV CD 1 63:02 2 Sequenza IXa for clarinet (1980) 14:01 Joaquin Valdepeñas 1 Sequenza I for flute (1958) 5:16 Recorded on 25th and 26th October, 2003 Nora Shulman Recorded on 21st November, 1999 3 Sequenza X for trumpet in C and pianoresonance (1984) 17:08 2 Sequenza II for harp (1963) 9:28 Guy Few Erica Goodman Recorded on 1st and 2nd October, 2000 Recorded on 7th October, 2000 4 Sequenza XI for guitar (1987-88) 16:28 3 Sequenza III for female voice (1966) 7:37 Pablo Sáinz Villegas Tony Arnold Recorded on 10th and 11th May, 2003 Recorded on 26th January, 2002 CD 3 58:48 4 Sequenza IV for piano (1966) 10:56 Boris Berman 1 Sequenza XII for bassoon (1995) 16:18 Recorded on 17th June, 1998 Ken Munday Recorded on 10th and 11th January, 2004 5 Sequenza V for trombone (1965) 5:34 Alain Trudel Recorded on 4th May, 2000 2 Sequenza XIII for accordion (chanson) (1995) 8:16 Joseph Petric 6 Sequenza VI for viola (1967) 14:53 Recorded on 18th December, 2000 Steven Dann 8.559259 Recorded on 17th and 18th June, 2002 3 Sequenza XIV for cello (2002) 13:09 Darrett Adkins 7 Sequenza VIIa for oboe (1969) 9:17 Recorded on 29th and 30th May, 2004 Matej ·arc Recorded on 11th and 12th January, 2002 4 Sequenza VIIb for soprano saxophone (1995) 7:15 Wallace Halladay CD 2 60:09 Recorded on 12th and 13th February, 2004 1 Sequenza VIII for violin (1976) 12:32 5 Sequenza IXb for alto saxophone (1981) 13:50 Jasper Wood Wallace Halladay Recorded on 16th and 17th December, 2000 Recorded on 5th and 6th September, 2003 All tracks recorded at St John Chrysostom Church, Newmarket, Ontario, Canada. -

SSFL:Layout 1.Qxd

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land – Music for String Quartet and Voice 7.30pm | Wednesday 24 April 2013 Britten Theatre With the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union Singing a Song in a Foreign Land – Music for String Quartet and Voice 7.30pm | Wednesday 24 April 2013 | Britten Theatre Sonnette der Elisabeth Barrett-Browning op 52, nos 1-3 Wellesz Anna Rajah soprano | Park Quartet 5 Songs for soprano and string quartet op 40 Weigl Céline Laly soprano | Gémeaux Quartett Poems to Martha op 66 Toch Luke Williams baritone | Matteo Quartet INTERVAL The Ellipse Tintner Anna Rajah soprano | Park Quartet Lettres de Westerbork Greif Céline Laly soprano | Yu Zhuang & Manuel Oswald violin The Leaden and the Golden Echo op 61 Wellesz Katie Coventry mezzo-soprano | Molly Cockburn violin | George Hunt cello Adrian Somogyi clarinet | Emas Au piano A co-production with Pro Quartet, Paris www.proquartet.fr A part of this programme was performed in a concert at the Goethe Institute Paris on 10 April, 2013. Singing a Song in a Foreign Land, curated by RCM professor Norbert Meyn, forms part of Project ESTHER in partnership with Jeunesse Musicale Schwerin, Exil Arte Vienna and Pro Quartet Paris. Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union www.esther-europe.eu This concert presents compositions for voice and string quartet by four Viennese composers who were lucky enough to escape from the Nazi persecution of Jews and settle in exile in Britain, the USA and New Zealand. They had to come to terms with enormous upheavals, uncertainty and often the loss of family members and friends. -

Anton Bruckner's First Symphony

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ANTON BRUCKNER’S FIRST SYMPHONY: ITS TWO VERSIONS AND THEIR RECEPTION Takuya Nishiwaki, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2009 Dissertation directed by: Professor James Ross School of Music Bruckner’s First Symphony exists in two versions: the Linz version and the Vienna version. It has been taken for granted that the Linz version is to be used when performing the First Symphony. This fact seems to suggest the musical superiority of the Linz version over the Vienna version. For more than seventy-five years, the Vienna version has been completely forgotten even though this version is the final version Bruckner himself made of the work. Bruckner revised many of his symphonies, resulting in many versions. Among them, the Vienna version of the First Symphony is the only final version which is neglected. However, the Vienna version was the only available score of the work for the first forty years after its publication in 1893. This situation is unique in the modern reception of Bruckner’s music. This thesis attempts to reappraise the validity of the current overt bias toward the Linz version by exploring both Bruckner’s working method and the history of the modern reception of the First Symphony. Biographical facts show that Bruckner had a strong personal motivation for the revision which was not triggered by any external factors. I shall demonstrate that the Vienna version has been undermined in the twentieth-century reception of Bruckner’s music through two separate modern critical editions. In particular, the main causes for the current bias toward the Linz version originated with the period of the first Bruckner Gesamtausgabe (1930-44) under the direction of Robert Haas.