Bruckner, Mahler and Anti-Semitism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol. 20, No. 3 The Organization of Canadian Symphony Musicians (ocsm)isthe voice of Canadian professional orchestral musicians. ocsm’s mission is to uphold and improve the working conditions of professional Canadian orchestral musicians, to promote commu- nication among its members, and to advocate on behalf of the Canadian cultural community. Editorial Vancouver dispute leads to By Barbara Hankins new rights for symphonic Editor extra musicians Does it matter to music lovers how the orchestra By Matt Heller looks? Many will say that people see us before they ocsm President hear us, and that ‘‘visual cohesion’’ is of paramount importance. Others say that a change of dress code In recent years, Vancouver Symphony musicians have from the stuffy tails and white tie is needed to break toured China, opened a new School of Music, and won down the barrier between the orchestra and audience. aGrammy Award. Atthe negotiating table, vso musi- Arlene Dahl’s article gives a clear overview of the cians have fought to keep pace with the city’s booming choices musicians and managements are considering. economy and to recover from a 25 per cent salary cut If you have an opinion on this, feel free to chime in on in 2000. The Vancouver Symphony’s last agreement the ocsm list or send me your thoughts for possible finished with the 2011–12 season, so negotiations use in the next Una Voce. should have begun last spring. What happened instead My personal view is was a contentious and complex dispute between the that while the dress vso Musicians Association (vsoma), and the Vancou- code should reflect our ver Musicians Association (vma), the afm Local repre- respect for our art and senting all unionized Vancouver musicians, including the tone of the concert, those in the vso. -

PAUL NETTL, EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BOHEMIA, and GERMANNESS ■ Martin Nedbal

386 ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES MUSIC HISTORY AND ETHNICITY FROM PRAGUE TO INDIANA: PAUL NETTL, EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BOHEMIA, AND GERMANNESS ■ Martin Nedbal Dedicated to the memory of Bruno Nettl (1930–2020) In 1947, musicologist Paul Nettl published The Story of Dance Music, his first book after his immigration to the United States from Nazi-occupied Czecho- slovakia.1 In their reviews of the book, two critics accused Nettl of Czech nationalism and chauvinism. Hungarian-born musicologist Otto Gombosi (1902–1955), who settled in the US in 1939, was particularly bothered by what he called Nettl’s „disturbing overemphasis on everything Slavic, and especially Czech.“2 German musicologist Hans Engel (1894–1970) went even further to make an explicit connection between Nettl’s scholarly work and his presumed ethnic identity. Engel was especially critical of Nettl’s claims that the minuets in multi-movement compositions by eighteenth-century composers of the so-called Mannheim School originated in Czech folk music and that the ac- centuated openings of these minuets (on the downbeat, without an upbeat) corresponded “to the trochaic rhythm of the Czech language which has no article.”3 Engel viewed such claims as resulting from “patriotic or nationalistic 1 Paul Nettl, The Story of Dance Music (New York: Philosophical Library, 1947). 2 Otto Gombosi, “The Story of Dance Music by Paul Nettl,” The Musical Quarterly 34, no. 4 (October 1948): 627. Gombosi was even more critical of Nettl’s minor comment about Smetana: “it is chauvinism gone rampant,” he wrote, “to say that ‘Smetana is … a more universal type of genius than Chopin who used only the piano to glorify national aspirations’.” 3 Nettl, The Story of Dance Music, 207; Hans Engel, “Paul Nettl. -

Mahler's Third Symphony and the Languages of Transcendence

Mahler’s Third Symphony and the Languages of Transcendence Megan H. Francisco A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2016 Stephen Rumph, Chair JoAnn Taricani Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ©Copyright 2016 Megan H. Francisco University of Washington Abstract Mahler’s Third Symphony and the Languages of Transcendence Megan H. Francisco Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Stephen Rumph Music History A work reaching beyond any of his previous compositional efforts, Gustav Mahler’s Third Symphony embodies cultural, political, and philosophical ideals of the Viennese fin-de- siècle generation. Comprising six enormous movements and lasting over ninety minutes, the work stretches the boundaries of symphonic form while simultaneously testing the patience of its listeners. Mahler provided a brief program to accompany his symphony, which begins with creation, moves through inanimate flowers to animals, before finally reaching humanity in the fourth movement. In this movement, Mahler used an excerpt from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra to introduce spoken language into the symphony. The relationship of music and language plays an integral role in Mahler’s expressive design of the Third Symphony, specifically in his vision of transcendence. Mahler creates a subtle transformation from elevated language (the fourth) to a polytextuality of folksong and onomatopoeia (the fifth) that culminates in the final, transcendent sixth movement. Throughout these last three movements, Mahler incorporates philosophical concepts from Nietzsche and his beloved Arthur Schopenhauer. In studying the treatment of language in these culminating movements, this thesis shows how Nietzsche’s metaphysical philosophies help listeners encounter and transcend Schopenhauer’s Will at the climactic end of the Third Symphony. -

Austrian Musicology After World War II

Prejeto / received: 17. 10. 2011. Odobreno / accepted: 9. 3. 2012. A USTRIAN MUSICOLOGY after WORLD WAR II BARBARA BOISITS Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien Izvleček: V primerjavi s povojno muzikologijo v Abstract: Whereas postwar musicology in Austria Avstriji, ki je bila trdno v rokah Ericha Schenka, was largely dominated by one figure, Erich je njen sedanji položaj precej drugačen. Poleg Schenk, the present situation is quite different: muzikoloških inštitutov na štirih univerzah in besides musicological institutes at the four na Avstrijski akademiji znanosti nastajajo še traditional universities and the Austrian Academy nove institucije, zlasti na univerzah za glasbo of Sciences, a number of other institutions in upodabljajoče umetnosti in v okviru zasebnih have been established, especially within the družb in ustanov, ki vodijo raznovrstne razisko- framework of the University of Music and valne projekte. Še vedno je prisoten poudarek Performing Arts, as well as of private societies na raziskovanju zgodovine glasbe v Avstriji, and foundations, all introducing a rich variety vendar z vedno večjim zavedanjem problemov, of research projects. Nevertheless, there is still ki jih vključuje nacionalna zgodovina glasbe. some focus on the history of music in Austria with a growing awareness of the problems a national history of music brings along. Ključne besede: Erich Schenk, Kurt Blaukopf, Keywords: Erich Schenk, Kurt Blaukopf, Harald Harald Kaufmann, Rudolf Flotzinger, Gernot Kaufmann, Rudolf Flotzinger, Gernot Gruber, Gruber, glasbena zgodovina Avstrije, avstrijski Music History of Austria, Austrian Music Lexicon, glasbeni leksikon, glasba – identiteta – prostor Music – Identity – Space The situation of today’s musicology in Austria reflects somehow quite appropriately the extremely successful history of the stereotype of Austria as the land of music.1 In other words, musicology in Austria benefits directly from the country’s rich musical life in past and presence, and in this respect the “land of music” is more than a cliché. -

N E W S L E T T

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICnewsletter Vol. 18, No. 1 Winter 2018 Chase, Spalding Named Professors of the Practice Harvard University Department of Music 3 Oxford Street Cambridge, MA 02138 617-495-2791 music.fas.harvard.edu INSIDE 3 Talking with Kate Pukinskis 4 Cuba-Harvard Connection 5 Braxton Shelley's Holy Power Foundation. courtesyPhoto MacDowell of Sound don’t believe that there’s a model for speranza Spalding joined the fac- 6 Faculty News the 2017 musician,” Professor of the ulty of the Department of Music 6 Graduate Student News Practice Claire Chase recently told an as Professor of the Practice, with “Iinformal gathering of undergraduate and gradu- Ean appointment that began in July 2017. 7 Alumni News ate students of the Music Department. “I believe Spalding will begin her teaching with two 10 Library News there are many modalities. I like that term because courses this spring: Songwriting Workshop 11 Undergraduate News modalities move. To be inspired by change is and Applied Music Activism. ideal in an organization, whether it be a band, Four-time Grammy award-winner, 11 David Dodman organization, school—it’s a way of being. Show jazz bassist, singer-songwriter, lyricist, 12 Bernstein's Young People's Concerts me an important artistic movement where artists humanitarian activist, and educator, Spald- didn’t struggle or come up with new modalities.” ing has five acclaimed solo albums and Chase, a MacArthur Fellow, co-founded the numerous music videos to her name. She is International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), recognized internationally for her virtuosic and with them has world-premiered well over singing and bass playing, her impassioned 100 works and helped create an audience for new improvisatory performances, and her cre- music. -

From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: the Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892)

From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: The Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892) María Cáceres-Piñuel All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 28/08/2019 Published: 03/04/2021 Last updated: 03/04/2021 How to cite: María Cáceres-Piñuel, “From Historical Concerts to Monumental Editions: The Early Music Revivals at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater (1892),” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (April 03, 2021) Tags: 19th century; Adler, Guido; Böhm, Josef; Cecilian Movement; Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich (DTÖ); Early music programming ; Hermann, Albert Ritter von; Historical concerts; International Exhibition of Music and Theater (Vienna 1892); Joachim, Amalie; National monumental editions This article is part of the special issue “Exploring Music Life in the Late Habsburg Monarchy and Successor States,” ed. Tatjana Marković and Fritz Trümpi (April 3, 2021). Most of the archival research needed to write this article was made possible thanks to a visiting fellowship in the framework of the Balzan Research Project: “Towards a Global History of Music,” led by Reinhard Strohm. I have written this article as part of my membership at the Swiss National Science Fund (SNSF) Interdisciplinary Project: “The Emergence of 20th Century ‘Musical Experience’: The International Music and Theatre Exhibition in Vienna 1892,” led by Cristina Urchueguía. I want to thank Alberto Napoli and Melanie Strumbl for reading the first draft of this text and for their useful suggestions. The cover image shows Ernst Klimt’s (1864–92) lithograph for the Viennese Exhibition of 1892 (by courtesy Albertinaof Sammlungen Online, Plakatsammlung, Sammlung Mascha). -

Ein Musikhistoriker Und Die Musik Seiner Zeit Guido Adler Zwischen Horror Und Amor

SBORNÍK PRACÍ FILOZOFICKÉ FAKULTY BRNĚNSKÉ UNIVERZITY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS H 38–40, 2003–2005 THEOPHIL Antonicek, WIEN EIN MUSIKHISTORIKER UND DIE MUSIK SEINER ZEIT GUIDO ADLER ZWISCHEN HORROR UND AMOR „Die Wissenschaft wird ihre Aufgabe in vollstem Umfange nur dann erreichen, wenn sie in lebendigem Kontakt mit dem Kunstleben bleibt.“1 Guido Adler, der diese Worte in seiner Selbstbiographie niederschrieb, hat sich diesem Anspruch immer gestellt. Er war seit seiner Jugend ein begeisterter Verehrer Richard Wag- ners, auch wenn dieser eine solche Verehrung einem Juden gewiß nicht leicht machte. Adler, der ja auch persönlich in Bayreuth und im Hause Wagners war, fand dafür die Formel „Wagner ist nicht Bayreuth“, die den Komponisten vor al- lem von der Interpretation Houston Chamberlains trennen wollte. Adler war Schü- ler und Bewunderer Bruckners, er stand in engem Kontakt mit Johannes Brahms, den er, ebenso wie später Gustav Mahler und Richard Strauss, als Vertreter der schöpferischen Musik in die Leitende Kommission der Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich holte. Die wohl engste Beziehung hatte er seit seiner Jugendzeit zu Gustav Mahler, dem er sich ja auch als Musikhistoriker zugewandt hat. Von den jüngeren Komponisten war er unter anderem, um nur die bekannteren zu nennen, mit Julius Bittner und Wilhelm Kienzl in freundschaftlicher Verbindung; die Be- ziehung zu Erich Wolfgang Korngold war vor allem durch dessen Vater, Adlers mährischen Landsmann Julius Korngold, gegeben. Diese und andere Komponi- stenbekanntschaften Adlers gingen nicht immer ganz ohne kleine Reibereien ab, doch dominierte, vor allem mit zunehmenden Jahren, der Geist der Freundschaft, den Adler seinen Mitmenschen entgegenzubringen pflegte. -

2017–18 Season Week 8 Beethoven Bruckner

2017–18 season andris nelsons music director week 8 beethoven bruckner Season Sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus supporting sponsorlead sponsor supporting sponsorlead thomas adès artistic partner Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to care and cure, but our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited future of healthcare. www.takeda.com Takeda is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra Table of Contents | Week 8 7 bso news 1 7 on display in symphony hall 18 bso music director andris nelsons 2 0 the boston symphony orchestra 23 parallel paths in early 20th-century music by jean-pascal vachon 3 2 this week’s program Notes on the Program 34 The Program in Brief… 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 43 Anton Bruckner 53 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 57 Rudolf Buchbinder 60 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on november 24 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2017 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Musicology in German Universities 17Riedrich 11Lume

Musicology in German Universities 17riedrich 11lume As is generally known, Germany is justly regarded as what may be called "the cradle of modern musicology."l "Modern musicology" in this sense stands for scholarly access to music on the basis of the principles and method of empirical learning, in contradistinction to the medieval concept of ars musica (vyith its two major spheres of scientia. and usus musicae) which meant scholarly access to music on the basis of numerical speculation and rational definition of the sounds. Once an indispensable (and at'times even compulsory) component of the academic curriculum and (in the Middle Ages) of the quadrivium, the study of music had slowly petered out and finally come to an end in the German universities between the last decades of the 16th century and the early 18th century. For a certain period there was an almost complete lacuna and the word musica was lacking altogether in the programs, although it was a gross exaggeration when Peter Wagner in 1921 pretended that this lacuna had lasted for two centuries. Of all German universities only Leipzig seems to have preserved the Medieval tradition, at least to some extent. The reputation of musica as a field of academic learning and the reputation of its teachers had decayed. In some caseS professors of mathematics had been offered the chairs of musica and in others the teaching of music had been attached to that of physics. Scientific leanings of music theorists dominated in the period of Johannes Kepler, Robert Fludd, Marin Mersenne, etc.-precursors of the division between the historical and the scientific conception of musicology that came to the fore in the 19th century. -

Recording Master List.Xls

UPDATED 11/20/2019 ENSEMBLE CONDUCTOR YEAR Bartok - Concerto for Orchestra Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop 2009 Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1978L BBC National Orchestra of Wales Tadaaki Otaka 2005L Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan 1965 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Ferenc Fricsay 1957 Boston Symphony Orchestra Erich Leinsdorf 1962 Boston Symphony Orchestra Rafael Kubelik 1973 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa 1995 Boston Symphony Orchestra Serge Koussevitzky 1944 Brussels Belgian Radio & TV Philharmonic OrchestraAlexander Rahbari 1990 Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer 1996 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Fritz Reiner 1955 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1981 Chicago Symphony Orchestra James Levine 1991 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Pierre Boulez 1993 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Paavo Jarvi 2005 City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle 1994L Cleveland Orchestra Christoph von Dohnányi 1988 Cleveland Orchestra George Szell 1965 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam Antal Dorati 1983 Detroit Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1983 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Tibor Ferenc 1992 Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra Zoltan Kocsis 2004 London Symphony Orchestra Antal Dorati 1962 London Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti 1965 London Symphony Orchestra Gustavo Dudamel 2007 Los Angeles Philharmonic Andre Previn 1988 Los Angeles Philharmonic Esa-Pekka Salonen 1996 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Charles Dutoit 1987 New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein 1959 New York Philharmonic Pierre -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

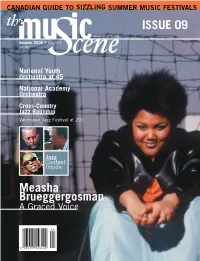

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting. -

Anmerkungen)1

[357] NOTES (ANMERKUNGEN)1 Gustav Mahler was born on July 7, 1860 in Kalischt (Bohemia). All analyses are based on the study scores, which differ in details of instrumentation from the large scores that are intended for performance and were corrected later. In that it was less important to pursue a practical treatise on instrumentation than to recognize the original intention, I believed I should be permitted to make use of the study scores, especially as these are also more easily accessible to the reader than the large ones. The following data are, when nothing else is noted, taken from Guido Adler’s commemorative Mahler publication (Gedenkschrift) that is cited in the bibliography. Other sources are individually noted. FIRST SYMPHONY Of the early works that were destroyed, those known by name are: Quintet for Strings and Piano. Sonata for Piano and Violin. Opera, Duke Ernst of Swabia (Herzog Ernst von Schwaben). Opera, The Argonauts (Die Argonauten). Fairy tale opera, Rübezahl Nordic Symphony (Adler). Draft of the First Symphony 1885, completion 1888. First performance 1889 in Pest, published 1898. At the performance in Pest, a program was not announced. At the two subsequent performances in Hamburg and Weimar (Music Festival [Tonkünstlerfest]), Mahler provided, according to a statement of Paul Stefan, the following program under the heading “Titan”: Part 1. From the Days of Youth, Pieces About Youth, Fruits, and Thorns. 1. Spring and No End. The introduction depicts the awakening of nature at earliest morning. (In Hamburg: Winter Slumber.) 2. Chapter of Flowers (Andante). 3. With Full Sails (Scherzo). Part 2.