Public Private Cooperation in Urban Redevelopment A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives

Governing Baltimore: A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives William G. LeFurgy, Susan Wertheimer David, and Richard J. Cox Baltimore City Archives and Records Management Office Department of Legislative Reference 1981 Table of Contents Preface i History of the Mayor and City Council 1 Scope and Content 3 Series Descriptions 5 Bibliography 18 Appendix: Mayors of Baltimore 19 Index 20 1 Preface Sweeping changes occurred in Baltimore society, commerce, and government during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From incorporation in 1796 the municipal government's evolution has been indicative of this process. From its inception the city government has been dominated by the mayor and city council. The records of these chief administrative units, spanning nearly the entire history of Baltimore, are among the most significant sources for this city's history. This guide is the product of a two year effort in arranging and describing the mayor and city council records funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. These records are the backbone of the historical records of the municipal government which now total over three thousand cubic feet and are available for researchers. The publication of this guide, and three others available on other records, is preliminary to a guide to the complete holdings of the Baltimore City Archives scheduled for publication in 1983. During the last two years many debts to individuals were accumulated. First and foremost is my gratitude to the staff of the NHPRC, most especially William Fraley and Larry Hackman, who made numerous suggestions regarding the original proposal and assisted with problems that appeared during the project. -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191. -

Inner Harbor West

URBAN RENEWAL PLAN INNER HARBOR WEST DISCLAIMER: The following document has been prepared in an electronic format which permits direct printing of the document on 8.5 by 11 inch dimension paper. If the reader intends to rely upon provisions of this Urban Renewal Plan for any lawful purpose, please refer to the ordinances, amending ordinances and minor amendments relevant to this Urban Renewal Plan. While reasonable effort will be made by the City of Baltimore Development Corporation to maintain current status of this document, the reader is advised to be aware that there may be an interval of time between the adoption of any amendment to this document, including amendment(s) to any of the exhibits or appendix contained in the document, and the incorporation of such amendment(s) in the document. By printing or otherwise copying this document, the reader hereby agrees to recognize this disclaimer. INNER HARBOR WEST URBAN RENEWAL PLAN DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND ORIGINALLY APPROVED BY THE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE BY ORDINANCE NO. 1007 MARCH 15, 1971 AMENDMENTS ADDED ON THIS PAGE FOR CLARITY NOVEMBER, 2004 I. Amendment No. 1 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance 289, dated April 2, 1973. II. Amendment No. 2 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. 356, dated June 27, 1977. III. (Minor) Amendment No. 3 approved by the Board of Estimates on June 7, 1978. IV. Amendment No. 4 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

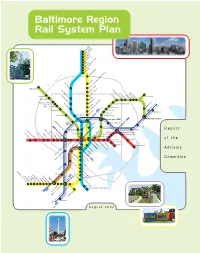

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Final Final Kromer

______________________________________________________________________________ CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VACANT-PROPERTY POLICY AND PRACTICE: BALTIMORE AND PHILADELPHIA John Kromer Fels Institute of Government University of Pennsylvania A Discussion Paper Prepared for The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy and CEOs for Cities October 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY SUMMARY OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS * DISCUSSION PAPERS/RESEARCH BRIEFS 2002 Calling 211: Enhancing the Washington Region’s Safety Net After 9/11 Holding the Line: Urban Containment in the United States Beyond Merger: A Competitive Vision for the Regional City of Louisville The Importance of Place in Welfare Reform: Common Challenges for Central Cities and Remote Rural Areas Banking on Technology: Expanding Financial Markets and Economic Opportunity Transportation Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality Signs of Life: The Growth of the Biotechnology Centers in the U.S. Transitional Jobs: A Next Step in Welfare to Work Policy Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest Open Space Protection: Conservation Meets Growth Management Housing Strategies to Strengthen Welfare Policy and Support Working Families Creating a Scorecard for the CRA Service Test: Strengthening Banking Services Under the Community Reinvestment Act The Link Between Growth Management and Housing -

City of Baltimore Phone Numbers

Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management City of Bernard C. “Jack” Young, Mayor BALTIMORE David McMillan, Director Maryland City of Baltimore Phone Numbers Residents can contact these phone numbers to access various City services (note: this is not an exhaustive list). Thank you for your patience during this IT outage. Baltimore City Council Office of the Council President 410-396-4804 District 1 410-396-4821 District 2 410-396-4808 District 3 410-396-4812 District 4 410-396-4830 District 5 410-396-4819 District 6 410-396-4832 District 7 410-396-4810 District 8 410-396-4818 District 9 410-396-4815 District 10 410-396-4822 District 11 410-396-4816 District 12 410-396-4811 District 13 410-396-4829 District 14 410-396-4814 Baltimore City Fire Department (BCFD) Headquarters 410-396-5680 Community Education & Special Events 410-396-8062 Office of the Fire Marshall 410-396-5752 Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD) Animal Control 311 B'More for Healthy Babies 410-396-9994 BARCS 410-396-4695 Community Asthma Program 410-396-3848 Crisis Information Referral Line 410-433-5175 Dental Clinic / Oral Health Services 410-396-4501 Druid Health Clinic 410-396-0185 Emergency Preparedness & Response 443-984-2622 Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management City of Bernard C. “Jack” Young, Mayor BALTIMORE David McMillan, Director Maryland Environmental Health 410-396-4424 Guardianship 410-545-7702 Health Services Request 443-984-3996 Immunization Program 410-396-4544 Lead Poisoning Prevention Program 443-984-2460 LTC Ombudsman 410-396-3144 Main Office 410-396-4398 -

Spring 2017 Roland Park News

Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Roland Park Community Foundation PAID 5115B Roland Avenue Permit 6097 Baltimore, MD 21210 Baltimore, MD Quarterly from the Roland Park Community Foundation • Volume Sixty-Four • Spring 2017 Remembering Al Copp Archer Senft’s Remarkable Journey Bookends: The Wayfarer’s Remembing the life of Al Cp Handbook: A As we mourn the loss of a wonderful neighbor and friend, we remember Al’s Field Guide for dedication to the Roland Park Community and his commitment to helping others. the Independent He worked tirelessly to help implement many major community projects, including the planting of new trees, the installation of upgraded streetlights, benches and Traveler trash receptacles in the neighborhood, the beautification of many crosswalks, and the restoration of Stony Run, as well as the Roland Water Tower. Al’s eorts and selfless spirit will never be forgotten. Our hearts go out to his family during this dicult time. hb eig o rh N r o o u d o 1999Y CAFE N E W S 2 31 Volume 64 • Spring 2017 fact that her family made money from the film, but it was the Editor’s Notes government that decided the “small, depressing, inconclusive, By Hilary Paska formerly of Wyndhurst, has moved into limited spool of celluloid” was worth $16 million, reaffirming its Roland Park Open Table of Contents larger premises on Deepdene Road and position as a true relic, one of the few in a secular world. What happened to winter? No snow storms, promises to be a fashion-forward addition to Space Campaign 2 Editor’s Notes Other important information 3 Arts Happenings shoveling, sledding…not even a single snow our local businesses. -

Mackenzie Office Building List MARKET REPORT OFFICE PROPERTIES, 2017 4TH QUARTER`

MacKenzie Office Building List MARKET REPORT OFFICE PROPERTIES, 2017 4TH QUARTER` Building Address & Name Class Submarket Region 2220 Boston St B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2400 Boston St (1895 Building / Factory Building) B+ Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2400 Boston St (Signature Building) B+ Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2701 Boston St (Lighthouse Point Yachting Center) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2809 Boston St (Tindeco Wharf Office) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 3301 Boston St (Canton Crossing II) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2200 Broening Hwy (Maritime Center I) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2310 Broening Hwy (Maritime Center 2) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2400 Broening Hwy (Bldg 2400 - Office) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 2500 Broening Hwy (Point Breeze Business Ctr) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 333 Cassell Dr (Triad Technology Center) A Baltimore City East Baltimore City 3601 Dillon St B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 5200 Eastern Ave (Mason Lord Bldg) C Baltimore City East Baltimore City 1407 Fleet St (Broom Corn Building) B+ Baltimore City East Baltimore City 3700 Fleet St (Southeast Professional Center) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 1820 Lancaster St (Union Box Building) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 98 N Broadway St (Church Hosiptal Professional Center) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 101 N Haven St (King Cork & Seal Building) B Baltimore City East Baltimore City 3601 Odonnell St (Gunther Headquarters) B Baltimore City East Baltimore -

Charles Center South 36 S

Under New FOR LEASE Ownership! Charles Center South 36 S. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21202 Situated on one of the city’s most recognizable intersections at the corner of Lombard Street and Charles Street BUILDING FEATURES • Upcoming renovations to the common areas including the main lobby and restrooms • Modernization of the elevators • Two on-site deli café operations • Full service on-site fitness center • Conference Center • On-site property management • On-site garage and ample parking available LOCATION FEATURES in adjacent garages • Charles Center South is located only one • 24-7 Lobby Attendant block from Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, the #1 tourist attraction in the state of Maryland, with Concierge Service • 14 million visitors annually and hundreds of amenities • The building benefits from excellent access to multimodal transportation • Located in HUB and Enterprise Zones Matthew Seward Senior Director +1 410 347 7549 [email protected] Brian P. Wyatt Director cushmanwakefield.com +1 410 347 7804 [email protected] cushmanwakefield.com FOR LEASE 36 South Charles Street Baltimore, MD TYPICAL FLOOR PLAN Up Down Main Elec. Fire Alarm FE Phone Down Up Flr. sink Elec. EWC FE AVAILABLE OFFICE SPACE Typical Floor Plan 1/8" = 1'-0" Charles Center South • Ground floor retail 846 RSF 36 South Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland James LloydA R C H I T E C T S P A • Ground Level 2,350 RSF 12935 Byefield Drive, Highland, Maryland 20777 • 410 531 1177 0 5 10 20 40 • 1st Floor/Suite 101 1,750 RSF • 8th Floor/Suite 803 13,040 RSF • 9th Floor/Suite 902 4,884 RSF • 11th Floor/Suite 500 6,178 RSF • 14th Floor/Suite 1400 6,152 RSF • 14th Floor/Suite 1404 A 1,841 RSF • 15th Floor/Suite 1530 2,971 RSF • 16th Floor/Suite 1600 13,040 RSF • 19th Floor/Suite 1920 6,545 RSF • 20th Floor/ Suite 2000 5,855 RSF • 23rd Floor/Suite 2310 2,281 RSF The information contained herein was obtained from sources we consider reliable. -

The Westside Baltimore, Maryland

AN ADVISORY SERVICES PANEL REPORT The Westside Baltimore, Maryland www.uli.org Cover Baltimore.indd 3 4/22/11 9:53 AM The Westside Baltimore, Maryland A Vision for the Westside Neighborhood December 5–10, 2010 An Advisory Services Program Report Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 About the Urban Land Institute he mission of the Urban Land Institute is to ●● Sharing knowledge through education, applied provide leadership in the responsible use of research, publishing, and electronic media; and land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. ULI is committed to ●● Sustaining a diverse global network of local practice T and advisory efforts that address current and future ●● Bringing together leaders from across the fields challenges. of real estate and land use policy to exchange best practices and serve community needs; Established in 1936, the Institute today has nearly 30,000 members worldwide, representing the ●● Fostering collaboration within and beyond ULI’s entire spectrum of the land use and development membership through mentoring, dialogue, and disciplines. ULI relies heavily on the experience of problem solving; its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set ●● Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, standards of excellence in development practice. regeneration, land use, capital formation, and The Institute has long been recognized as one of the sustainable development; world’s most respected and widely quoted sources of ●● Advancing land use policies and design practices objective information on urban planning, growth, that respect the uniqueness of both built and natural and development.