Politics, Public Policy and Multiculturalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd. Thesis Understanding Indigenous

PhD. Thesis Understanding Indigenous Entrepreneurship: A Case Study Analysis. A paper presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Queensland October 2004. Dennis Foley School of Business THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Accepted for the award of Supervisors: Dr. Maree Boyle Griffith university Dr. Judy Drennan Queensland university of Technology Dr. Jessica Kennedy university of central Queensland CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY 8 ACRONYMS 9 LIST OF FIGURES 10 LIST OF ATTACHMENTS/APPENDIX 11 ABSTRACT 12 1. INTRODUCTION 14 1.1 THE RESEARCH PROJECT 14 1.2 NEED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN BUSINESSES 15 1.3 THE RESEARCH CONCEPTS 17 1.4 OUTLINE OF THE CHAPTERS: THE RESEARCH PROJECT. 19 2 INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA & HAWAII 22 2.1 DEFINITION OF AN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN AND INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 22 2.2 AN AUSTRALIAN CULTURAL CONSIDERATION 24 2.3 DEFINITION OF A NATIVE HAWAIIAN AND NATIVE HAWAIIAN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 25 2.4 AN HAWAIIAN CULTURAL CONSIDERATION 27 2.5 WHO IS AN INDIGENOUS ENTREPRENEUR? 30 2.6 PRE-COLONIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP 34 2.7 CONCLUSION 37 3 LITERATURE REVIEW 40 3.1 INTRODUCTION 40 3.2 INDIGENOUS SMALL BUSINESS THEORY 41 3.3 ETHNIC THEORIES 42 3.3.1 CULTURAL THEORY 42 3.3.2 ETHNIC ENCLAVE THEORY 44 3.3.3 MIDDLEMEN MINORITY/RESPONSE TO CULTURAL ANTAGONISM THEORY 46 3.3.4 OPPORTUNITY/ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION THEORY 47 3.3.5 INTERACTIVE THEORIES 49 3.4 CONCLUSION AND SUMMARY OF ETHNIC SMALL BUSINESS THEORIES IN AUSTRALIA 50 3.5 SOCIAL IDENTITY THEORY 50 3.6 CO-CULTURAL -

Coresearch (1977)

212##1977 A monthly pUblicationfor CSIRO staff January/February 1977 III New Chief Or IllN WllSH lOBEODME for Tropical Crops and INDUSTRY OONSUlTINJ Pastures Dr Alan Walsh-scientist, inventor and entrepreneur-retired from CSIRO on Dr E.F. (Ted) Henzell has been 5 January after 30 years of research, and 15 years as Assistant Chief, at the appointed the new Chief of the Division of Tropical Crops and Division of Chemical Physics. The Division has arranged a buffet dinner in his Pastures. honour at the Monash University Club on Saturday 26 February to which staff, Hew-ill take up his new duties on the retirement next month of their husbands/wives, and friends have been invited. the present Chief, Dr Mark 'I've been to so many farewell dinners recently that I'm beginning to acquire Hutton. a taste for wine,' Alan said, a little overwhelmed by the fuss being made of his Dr ... Henzcll. who has been the Division's Assistant Chief since departure. 1'970, . graduated B.Agr.Sc. from And Alan makes the point that he is not retiring from work. He intends the .. University of Queensland in taking a holiday for three months to recharge his batteries and then become a 1952. Dr Alan Walsh In the same year he was awarded private consultant to industry. a Rhodes Scholarship and under took research work at the De For unlike many other scientists ralia a head-start over the rest of Alan concedes that the research partment of Agriculture, Oxford A1an enjoys mixing with the cap· the world in the technique. -

The Australian Women's Health Movement and Public Policy

Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Gray Jamieson, Gwendolyn. Title: Reaching for health [electronic resource] : the Australian women’s health movement and public policy / Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson. ISBN: 9781921862687 (ebook) 9781921862670 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Birth control--Australia--History. Contraception--Australia--History. Sex discrimination against women--Australia--History. Women’s health services--Australia--History. Women--Health and hygiene--Australia--History. Women--Social conditions--History. Dewey Number: 362.1982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface . .vii Acknowledgments . ix Abbreviations . xi Introduction . 1 1 . Concepts, Concerns, Critiques . 23 2 . With Only Their Bare Hands . 57 3 . Infrastructure Expansion: 1980s onwards . 89 4 . Group Proliferation and Formal Networks . 127 5 . Working Together for Health . 155 6 . Women’s Reproductive Rights: Confronting power . 179 7 . Policy Responses: States and Territories . 215 8 . Commonwealth Policy Responses . 245 9 . Explaining Australia’s Policy Responses . 279 10 . A Glass Half Full… . 305 Appendix 1: Time line of key events, 1960–2011 . -

The Politics of Multiculturalism

The Politics of Multiculturalism The Politics of Multiculturalism Raymond Sestito 1(c~~1 THE CENTRE FOR INDEPENDENT STUDIES 1982 First pUblished August 1982 by The Centre for Independent Studies All rights reserved Views expressed in the publications of the Centre for Independent Studies are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre's staff, Advisers, Trustees, Directors or officers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Sestito, Raymond, 1955-. The politics of multiculturalism. Bibliography ISBN 0 949769 06 1. 1. Mul ticul turalism - Australia. 2. Australia - Politics and government - 1976-. I. Centre for Independent Studies (Australia). II. Title. (Series: CIS policy monographs; 3). 320.994 <!) The Centre for Independent Studies 1982 iv Contents The Author vi Acknowledgements vi Foreword Michael James vii The Politics of Multiculturalism Introduction 1 The Absence of Migrant Issues 3 2 A New Approach 10 3 Party Initiative 16 4- The Greek and Italian Response 23 5 The Limits of Multiculturalism 30 Notes 37 Further reading 41 v The Author Raymond Sestito is currently a tutor in the Department of Politics at La Trobe University where he is also undertaking graduate studies. Ack~owledgements I wish to acknowledge the assistance given to me by the Greek and Italian organisations - The Italian Assistance Association (CoAsIt), The Australian Greek Welfare Society, and FILEF, and the help given to me by the Victorian Ministry of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs. I should also like to thank the readers of earlier drafts of this paper and the Centre for Independent Studies for giving me the opportunity to publish it. -

Australia's Constitution

ustralia’s ConstitutionA An information booklet brought to you by the Federal Member for Riverina MICHAEL McCORMACK MP UNITED IN PEACE, TOGETHER WE STAND Australia’s nationhood, unlike many other countries of the world, was achieved with a vote, not a war. Our democratic Parliament was founded in 1901 after many years of grand speeches, negotiations and meetings. Premier Sir Henry Parkes (1815-96), who served five terms as Premier of New South Wales, is remembered BIG NEWS: How The Wagga Wagga Express as the “Father of Federation”, even though he did not reported the inaugural Federal elections. live to see its creation. VISION SPLENDID: Snow-capped mountains are a magnificent backdrop to He was a passionate advocate for uniting the six Parliament House. colonies. On 24 October 1889, at the Tenterfield School of Arts, Sir Henry delivered his famous Federal Member for Riverina MICHAEL McCORMACK MP Tenterfield Oration. The new parliament had the authority to make decisions about communications, currency, customs, This speech was seen as a clarion call to federalists defence, quarantine restrictions, trade and other and he called for a convention “to devise the Melbourne was the seat of government until the It is so important that we encourage everyone, matters. constitution which would be necessary for bringing Provisional Parliament House in Canberra began especially young people, to take an interest in politics into existence a federal government with a federal operation on 9 May 1927. The present 4700-room and the way in which our country is governed. I hope Australia’s new flag was soon flying proudly across parliament for the conduct of national undertaking”. -

Australian Journey Resource Guide

Australian Journey The Story of a Nation in 12 Objects Resources for the Journey Texts to Read | Websites to Visit Podcasts to listen to | Film and Literature Primary Sources |Defining Moments This booklet is produced by the Australian National University as a free educational resource. We gratefully acknowledge our collaboration with Monash University, the National Museum of Australia and all the cultural institutions featured in this project. Join us on an Australian Journey Australian Journey is designed for anyone, anywhere interested in Australia. Exploring the themes of Land, People, and Nation, it offers a road map to our country’s Past, Present, and Future. Australian Journey will take you the length and breadth of the continent, and across almost four billion years of history, in 12 short and engaging episodes. And every episode uses objects to reveal the stories of a nation. What do these pieces of the past tell us about their time, their purpose and their maker? Some of the objects we have chosen are famous, iconic or familiar; others obscure, even quirky. But all our objects tell a story and all find a place in the National Museum of Australia. Australian Journey is presented by Professor Bruce Scates and Dr Susan Carland. Resources for the Journey This booklet recommends a range of resources to complement each episode of Australian Journey. School teachers, international university students and the general public can use this guide to find texts, websites, podcasts, films, and literature to augment teaching and learning about the Australian nation. A collection of written, audio, internet and visual sources, this booklet will enable you to extend your knowledge of Australian history and engage further in the historical debates around the objects featured in Australian Journey. -

Australian Human Rights Commission

HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Papers presented at the 8th Annual Lalor Address on Community Relations held at Adelaide on 3 December 1982 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1983 Commonwealth of Australia 1983 ISSN 0314-3694 CONTENTS Page Official welcome Mr Jeremy Long, Commissioner for Community Relations The Hon. Dame Roma Mitchell 5 Chairman, Human Rights Commission Mr Les Nayda 16 Secretary to the Office of Aboriginal Affairs of South Australia Mr Joe Doueihi 29 President, World Lebanese Cultural Union for Australia and New Zealand iii OFFICIAL WELCOME BY MR J.P.M. LONG, COMMISSIONER FOR COMMUNITY RELATIONS Dame Roma Mitchell and members of the Human Rights Commission, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, Welcome to this the 8th Annual Lalor Address on Community Relations. At dawn on 3 December 128 years ago - it was a Sunday - a force of soldiers and police advanced upon and overwhelmed a group of armed gold miners in a makeshift stockade near Ballarat. No two of the several accounts of this engagement that I have read agree on the casualties but at least twenty-two and possibly thirty or more men died, most of them on the miners' side. The battle of the Eureka Stockade remains the major civil disturbance or riot in Australia's history and it might well be appropriate to commemorate the occasion for this reason alone. Not many countries have enjoyed a comparable absence of civil strife. But this was not the central reason, as I understand it, for Eureka Day being chosen for an annual address on community relations. And, since this is the first time that the Annual Lalor Address has been given in Adelaide - and only the second time it has been given outside Canberra - it may be appropriate for me to say something about the reason for choosing to celebrate Eureka Day in this way. -

The Living Daylights 2(14) 9 April 1974

University of Wollongong Research Online The Living Daylights Historical & Cultural Collections 4-9-1974 The Living Daylights 2(14) 9 April 1974 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1974), The Living Daylights 2(14) 9 April 1974, Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.2 no.14, April 9 - 22, 28p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/24 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Living Daylights 2(14) 9 April 1974 Publisher Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.2 no.14, April 9 - 22, 28p This serial is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/24 Vol.2 No. 14 April 9-22 1974 Pissweak on principles but!. End of term report Friday and monday are our key production days, which makes an easter Daylights impossible. This issue must suffice for a fortnight, till april 22, then we're back every tuesday. What a week. It's only politics, but if the terrible twosome get in . THUD! a plagiarised potpourri of news, views People in this office are and trivia with MIKE MORRIS rushing around trying to get on an electoral roll — prefer ably in an electorate with a swinging seat. And anarchist 18 year olds, dont YOU forget to register. just this once. Naturally Mungo IViacCallum has weighed in with a blast Fowl power from Canberra, where the long knives are already flashing, SOME POLITICIANS have their prior (see opposite) and even ities in the right place, I’m pleased to notorious non-voter Harry learn. -

History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: an Ethnography

History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography Gil Hardwick BA.Hons BLitt.Hons M.Crim.Just (W.Aust) SFSPE Senior Research Anthropologist Independent Social and Environmental Audit Perth, July 2019 History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography Gil Hardwick BA.Hons BLitt.Hons M.Crim.Just (W.Aust) SFSPE Senior Research Anthropologist Independent Social and Environmental Audit Perth, Western Australia July 2019 History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography. Author: Hardwick, Gil. Published by eBooks West West Perth, 2005, Western Australia Cover image, Wikipedia Commons Cover Design by Gil Hardwick Typeset by the author. Copyright © Gil Hardwick 2019 ISBN: 978-0-9923704-9-7 (ebook) The right of Gilbert John Hardwick to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968. CONTENTS Author Biography and Declaration of Interest i Introduction iii Locating the Central Murray Geography 1 History 5 Philosophy 10 Politics 11 Human Dynamics Confrontation 17 Consequences 23 Transhumance 28 The Drought Myth Innovation 32 Division 37 Federation 40 Panic 46 Prospects for Participatory Reform Dispute 51 Remediation 54 Community 60 Conclusion 63 Author Biography and Declaration of Interest The author of this study was born in Griffith, NSW, and grew up from the age of four in Deniliquin. He is directly descended along many lines from early pioneering families dating from the 1840s along the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Lachlan Rivers; from Port Phillip in Victoria, Kapunda and Mount Gambier in South Australia, Morago and Pretty Pine on the Deniliquin Run, to Merriwagga, Hillston, Temora and beyond. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1982

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 31 AUGUST 1982 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy Papers 31 August 1982 635 TUESDAY, 31 AUGUST 1982 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. S. J. Muller, Fassifem) read prayers and took the chair at 11 a.m, PAPERS The foUowing paper was laid on the table, and ordered to be printed:— Report of the State Electricity Commission of Queensland for the year ended 30 June 1982 The following i>apers were laid on the table:— Reports— Queensland Law Reform Commission for the year ended 30 June 1982 Pyramid SeUuig Schemes Elimination Committee for the year ended 30 June 1982 Proclamation under the Forestry Act 1959-1981 Orders in Council under— State Housing Act 1945-1981 State Housing (Freeholdmg of Land) Act 1957-1980 City of Brisbane Act 1924-1980 Expjlosives Act 1952-1981 Forestry Act 1959-1981 Regulations under— Co-operative and Other Societies Act 1967-1978 Water Act 1926-1981 By-laws under the Water Act 1926-1981 Information relating to payments under the Pensioner Rate Subsidy Scheme 636 31 August 1982 Ministerial Statements MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS Investigations by Private Consultants into Railway Department Hon. D. F. LANE (Merthyr—Minister for Transport) (11.3 a.m.): It is my duty to report to ParUament on a Cabinet decision yesterday in relation to the Railway Department. By direction, I have instructed the Commissioner for RaUways and general managers throughout the State that provisions of the Railways Act should be used, when considered appropriate, in relation to bans imposed -

The End of the White Australia Policy in the Australian Labor Party; a Discursive

1 The End of the White Australia Policy in the Australian Labor Party; a discursive analysis with reference to postcolonialism and whiteness theory. Luke Whitington, 2012. Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for BA Hons in History, University of Sydney. 1 2 Abstract Labor leaders ended their commitment to a White Australia in response to the experience of the Second World War and societal changes brought about by post-war non-British migration. Previous scholarship erroneously credits the ‘baby-boomer’ generation and the ‘middle-classing’ of the ALP. Changing the policy did not mean abandoning the Australian national project or ceding control of the spaces and bodies of the nation to non-white people. Immigration would continue to be controlled to preserve working conditions and democracy. The Whitlam Government’s move toward non-racial civic nationalism proscribed racial discrimination but was productive of discourses of white Australian nationalism. 2 3 Contents Introduction Chapter 1: 'Generally and genuinely popular': Early Support & Criticisms, Post- War Debate and the First Attempts at Change. Chapter 2: ‘No Sir, it is out of date and makes for war, so please count me as one against it’, Controversy, Change, Causes, Continuity. Chapter 3: White nationalism, civic liberal nationalism, Labor nationalism, Whitlam and whiteness. Conclusion 3 4 Introduction This thesis will explore why, how, and in what sense, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) rejected the White Australia policy. From the Second World War onwards and culminating in 1975, the ALP’s position on immigration changed from race-based exclusion to anti-racism. In doing so it removed a foundation from its Platform that it had adhered to since its inception as a political movement. -

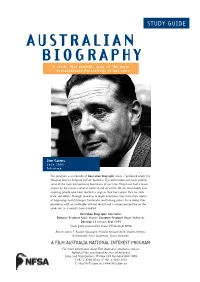

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Jim Cairns 1914–2003 Politician This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 7 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Jim Cairns Director/Producer Robin Hughes Executive Producer Megan McMurchy Duration 26 minutes Year 1999 Study guide prepared by Diane O’Flaherty © NFSA Also in Series 7: Rosalie Gascoigne, Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, Charles Perkins, Bill Roycroft, Peter Sculthorpe, Victor Smorgon A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: JIM CAIRNS 2 SYNOPSIS WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS? Throughout the 1960s and 70s Dr Jim Cairns held a unique position In the Labor Party in Australian public life as the intellectual leader of the political left.