Fishermen in War Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'British Small Craft': the Cultural Geographies of Mid-Twentieth

‘British Small Craft’: the cultural geographies of mid-twentieth century technology and display James Lyon Fenner BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 Abstract The British Small Craft display, installed in 1963 as part of the Science Museum’s new Sailing Ships Gallery, comprised of a sequence of twenty showcases containing models of British boats—including fishing boats such as luggers, coracles, and cobles— arranged primarily by geographical region. The brainchild of the Keeper William Thomas O’Dea, the nautical themed gallery was complete with an ocean liner deck and bridge mezzanine central display area. It contained marine engines and navigational equipment in addition to the numerous varieties of international historical ship and boat models. Many of the British Small Craft displays included accessory models and landscape settings, with human figures and painted backdrops. The majority of the models were acquired by the museum during the interwar period, with staff actively pursuing model makers and local experts on information, plans and the miniature recreation of numerous regional boat types. Under the curatorship supervision of Geoffrey Swinford Laird Clowes this culminated in the temporary ‘British Fishing Boats’ Exhibition in the summer of 1936. However the earliest models dated back even further with several originating from the Victorian South Kensington Museum collections, appearing in the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883. 1 With the closure and removal of the Shipping Gallery in late 2012, the aim of this project is to produce a reflective historical and cultural geographical account of these British Small Craft displays held within the Science Museum. -

David Duggleby Auctioneers & Valuers

David Duggleby Auctioneers & Valuers The Summer Picture Sale The Saleroom Vine Street Scarborough Staithes Group, Weatherill Family, Collection Ships Portraits, North Yorkshire Maritime Subjects and other 18th, 19th & 20th century oils & YO11 1XN watercolours United Kingdom Started 08 Jun 2015 11:00 BST Lot Description 1 Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): 'Wreck of the Polka' Whitby, watercolour, initialled and titled on the mount 28cm x 38cm 2 Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): Black Nab Saltwick Bay Whitby, watercolour initialled and dated 1864, 24cm x 33cm Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): 'Wreck of the Royal Rose' on Upgang Beach, watercolour and pencil, titled and inscribed 3 verso 22.5cm x 30cm Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): Whitby Fishing Coble 'Ararat' on Tate Hill Sands, watercolour initialled and dated 1864, 4 24cm x 37cm 5 Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): The Whitby Coble 'Thomas & William', watercolour initialled 25cm x 33cm Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): Studies of Whitby Fishing Cobles, two watercolour and pencil initialled and dated July /63 & 6 June 21st 1862, each approx 8cm x 15cm framed as one Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): The Hull Fishing Coble 'HL 351', watercolour and pencil initialled and dated June 7th 1863, 7 18cm x 25cm Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): Whitby Schooner 'The Fowler', watercolour and pencil initialled and dated July 7th 1864, 8 23cm x 18cm 9 Sarah Ellen Weatherill (British 1836-1920): Study of a Fishing Boat, -

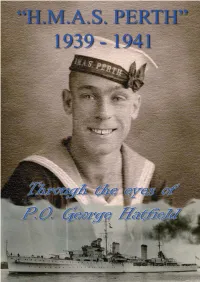

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021

Document Control Title Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021 Authors T Barnfield; E Johnston; T Dixon; K Saunders; E Siegal Approver(s) V Morgan; J Duffill Telsnig; N Greenwood Owner T Barnfield Revision History Date Author(s) Version Status Reason Approver(s) 19/06/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.1 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A 06/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.2 Draft Internal QA of V Morgan E Johnston Introduction and Part A 07/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 14/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.4 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A JNCC comments 26/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.1 Draft Part B & C N Greenwood E Johnston 29/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.2 Draft Internal QA of Part B N Greenwood E Johnston & C 30/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 05/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.4 Draft Part B & C JNCC N Greenwood E Johnston comments 06/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.0 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston compilation 07/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.1 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston Internal QA 18/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.2 Draft Whole document A Doyle E Johnston JNCC QA 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.3 Draft Whole Document G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.4 Draft Update following G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/01/2021 T Barnfield; V2.0 – 2.4 Draft Updates following NGreenwood; K Saunders; new data availability J Duffill Telsnig T Dixon; E and QA Siegal 01/02/2021 T Barnfield; V2.5 Final Finalise comments Nick Greenwood K Saunders; E and updates Siegal 1 Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2020 Contents Document Control ........................................................................................................... -

FOUL PLAY NOT to BUY JANET TAKES a DIVE Top Tips on Yacht Charter New Diesel SACRE BLEU! Dilemma Andy Struthers Endures French Berthing CARESSA Clinches It!

The Channel Sailing Club Magazine WINTER 2014 TO BUY OR FOUL PLAY NOT TO BUY JANET TAKES A DIVE top tips on yacht charter New diesel SACRE BLEU! dilemma Andy Struthers endures French berthing CARESSA clinches it! Over the top WW1 fun and games on the Icicle www.channelsailingclub.org WAVELENGTH WAVELENGTH Wavelength The Channel Sailing EDITOR’S NOTE Club magazine A WORD FROM THE COMMODORE Welcome to the winter 2014 edition of Wavelength. EDITOR Anyone struggling to find a berth on a sunny summer day Simon Worthington in the Solent will be amused by Andy Struthers’ tale of pontoon bashing in Brittany. And if you’re thinking of hiring ART DIRECTOR Marion Tempest a boat for a trip to France, then we have an essential guide to yacht charter. There is a busy diary of club sailing events PLEASE SEND ANY LETTERS AND “As the sun sets” in 2015 too, so there’s no excuse to not get on the water. PICTURES TO And now’s the time to give your sailing kit a makeover, so [email protected] read John Futcher’s top tips. Wishing everyone a Merry s it really a year since the last AGM, dependent, taking to the water. It’s a splendid CLUB NIGHT Xmas and a Happy New Year. Simon where has the time gone? It’s been organisation and well worth your support. Channel Sailing Club meets every so busy; your committee has been The club has sent them £300, a result of 50% Wednesday at The Old Freemen’s CHANNEL SAILING CLUB Clubhouse, City of London Isuperb at picking up the previous of our various raffles profits. -

Heritage Framework Book

Chapter Eight Urbanization, 1880 to 1930 Industrial Expansion and the Gilded Age Progressive Era The Roaring Twenties 1880 to 1900 1900 to 1920 1920 to 1929 1880’s 1888 1900 1900-1910 1914-1918 1920 1929 ||||||| Skipjack America’s Region Internal World Region Stock sailboats first electrified population combustion War I population Market first trolley line, reaches engines exceeds Crash produced Richmond 3 million 4.5 million AN ECOLOGY OF PEOPLE SIGNIFICANT EVENTS AND PLACE ▫ 1880’s–wooden ▫ 1894–protestors, ▫ 1918–worldwide skipjack sailing known as Coxey’s Spanish influenza Ⅺ PEOPLE vessels specially Army, march on epidemic strikes adapted to Washington region Extraordinary changes swept across the Chesapeake waters demanding economic ▫ first produced reform 1918–Migratory Bird United States and the world between Treaty Act outlaws 1880 and 1930 (see Map 10). These ▫ 1882–Virginia ▫ 1898 to 1899– killing of whistling changes continued to alter Chesapeake Assembly approves Spanish-American swans, establishes funding to establish War fought with hunting seasons, and Bay life, from the countryside to the city. Normal and Spain sets bag limits on The region’s population doubled, from Collegiate Institute international ▫ 2.5 million in 1880 to 5 million by 1930. for Negroes and 1900–region migratory waterfowl Central Hospital for population reaches Many of these people settled in estab- ▫ mentally ill African- 3 million 1920–regional population exceeds lished rapidly expanding urban centers Americans in ▫ 1900 to 1910– 4.5 million such as Baltimore, Washington, Petersburg internal combustion ▫ Richmond, and Norfolk. Washington’s ▫ 1886–adoption of engines power first 1921–captured numbers grew at an incredible pace, ris- standard gauge links commercially German battleship successful wheeled Ostfriesland ing from about 75,000 in 1880 to 1.4 mil- all railroads in region and nation vehicles and (renamed the San lion by 1920. -

Study on Ownership and Exclusive Rights of Fisheries Means of Production

Study On Ownership and Exclusive Rights of Fisheries Means of Production Final Report Service Contract: EASME/EMFF/2016/1.3.2.1/SI2.766458 MRAG, AZTI & NEF February – 2019 Final Report EUROPEAN COMMISSION Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME) Unit A.3 — EMFF E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Study on ownership and exclusive rights of fisheries means of production Service Contract: EASME/EMFF/2016/1.3.2.1/SI2.766458 EASME/EMFF/2017/016 Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME) European Maritime and Fisheries Fund 2018 EN Final Report Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 ISBN: 978-92-9202-453-6 doi: 10.2826/246952 © European Union, 2019 Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................ I LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................ -

An Overview of the Lithostratigraphical Framework for the Quaternary Deposits on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf

An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf Marine Geoscience Programme Research Report RR/11/03 HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are book- marked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub- headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MARINE GEOSCIENCE PROGRAMME The National Grid and other RESEARCH REPORT RR/11/03 Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords Group; Formation; Atlantic margin; North Sea; English Channel; Irish An overview of the lithostratigraphical Sea; Quaternary. Front cover framework for the Quaternary deposits Seismic cross section of the Witch Ground Basin, central North on the United Kingdom continental Sea (BGS 81/04-11); showing flat-lying marine sediments of the Zulu Group incised and overlain shelf by stacked glacial deposits of the Reaper Glacigenic Group. Bibliographical reference STOKER, M S, BALSON, P S, LONG, D, and TAppIN, D R. 2011. An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf. British Geological Survey Research Report, RR/11/03. -

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY to Vibyasxg-ER by Thesi S Submit

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY TO VIBYASXg-ER By Sisirlcumar Baa Thesi s submit ted for the Ph.D. degree in the University of London* June 1963 ProQuest Number: 10731585 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731585 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgment Transliteration Abbreviations; Chapter I. Introduction 1-32 Chapter II. The beginnings of Bengali prose 33-76 Chapter III. William Carey 77-110 Chapter IV. Ramram Basu 110-154 Chapter V. M?ityun;ja^ Bidyalaqikar 154-186 Chapter VI. Rammohan Ray 189-242 Chapter VII. Early Newspapers (1818-1830) 243-268 Chapter VUI.Sarpbad Prabhakar: Ii^varcandra Gupta 269-277 Chapter IX. Tattvabodhi#! Patrika 278-320 Chapter X. Vidyasagar 321-367 Bibli ography 36 8-377 —oOo** ABSTRACT The present thesis examines the growth of Bengali prose from its experimental Beginnings with Carey to its growth into full literary stature in the hands of Vidyasagar. The subject is presented chronologically and covers roughly the first half of the 1 9 th century. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The MARINER's MIRROR the JOURNAL of ~Ht ~Ocitt~ for ~Autical ~Tstarch

The MARINER'S MIRROR THE JOURNAL OF ~ht ~ocitt~ for ~autical ~tstarch. Antiquities. Bibliography. Folklore. Organisation. Architecture. Biography. History. Technology. Art. Equipment. Laws and Customs. &c., &c. Vol. III., No. 3· March, 1913. CONTENTS FOR MARCH, 1913. PAGE PAGE I. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY 4· A SHIP OF HANS BURGKMAIR. FISHING VESSELS. BY R. BY H. H. BRINDLEY • • 8I MORTON NANCE • • . 65 5. DocuMENTS, "THE MARINER's 2. NOTES ON NAVAL NOVELISTS. MIRROUR" (concluded.) CON· BY OLAF HARTELIE •• 7I TRIBUTED BY D. B. SMITH. 8S J. SOME PECULIAR SWEDISH 6. PuBLICATIONS RECEIVED . 86 COAST-DEFENCE VESSELS 7• WORDS AND PHRASES . 87 OF THE PERIOD I]62-I8o8 (concluded.) BY REAR 8. NOTES . • 89 ADMIRAL J. HAGG, ROYAL 9· ANSWERS .. 9I SwEDISH NAVY •• 77 IO. QUERIES .. 94 SOME OLD-TIME SHIP PICTURES. III. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY FISHING VESSELS. BY R. MORTON NANCE. WRITING in his Glossaire Nautique, concerning various ancient pictures of ships of unnamed types that had come under his observation, Jal describes one, not illustrated by him, in terms equivalent to these:- "The work of the engraver, Israel van Meicken (end of the 15th century) includes a ship of handsome appearance; of middling tonnage ; decked ; and bearing aft a small castle that has astern two of a species of turret. Her rounded bow has a stem that rises up with a strong curve inboard. Above the hawseholes and to starboard of the stem is placed the bowsprit, at the end 66 SOME OLD·TIME SHIP PICTURES. of which is fixed a staff terminating in an object that we have seen in no other vessel, and that we can liken only to a many rayed monstrance. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Maritime Craft Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: A thesaurus of maritime craft. Date: February 2020 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST AIRCRAFT CATAPULT VESSEL CATAPULT ARMED MERCHANTMAN AMPHIBIOUS VEHICLE BLOCK SHIP BOARDING BOAT CABLE LAYER CRAFT CANOE CATAMARAN COBLE FOYBOAT CORACLE GIG HOVERCRAFT HYDROFOIL LOGBOAT SCHUIT SEWN BOAT SHIPS BOAT DINGHY CUSTOMS AND EXCISE VESSEL COASTGUARD VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER CUSTOMS BOAT PREVENTIVE SERVICE VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER DREDGER BUCKET DREDGER GRAB DREDGER HOPPER DREDGER OYSTER DREDGER SUCTION DREDGER EXPERIMENTAL CRAFT FACTORY SHIP WHALE PROCESSING SHIP FISHING VESSEL BANKER DRIFTER FIVE MAN BOAT HOVELLER LANCASHIRE NOBBY OYSTER DREDGER SEINER SKIFF TERRE NEUVA TRAWLER WHALER WHALE CATCHER GALLEY HOUSE BOAT HOVELLER HULK COAL HULK PRISON HULK 2 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST SHEER HULK STORAGE HULK GRAIN HULK POWDER HULK LAUNCH LEISURE CRAFT CABIN CRAFT CABIN CRUISER DINGHY RACING CRAFT SKIFF YACHT LONG BOAT LUG BOAT MOTOR LAUNCH MULBERRY HARBOUR BOMBARDON INTERMEDIATE PIERHEAD PONTOON PHOENIX CAISSON WHALE UNIT BEETLE UNIT NAVAL SUPPORT VESSEL ADMIRALTY VESSEL ADVICE BOAT BARRAGE BALLOON VESSEL BOOM DEFENCE VESSEL DECOY VESSEL DUMMY WARSHIP Q SHIP DEGAUSSING VESSEL DEPOT SHIP DISTILLING SHIP EXAMINATION SERVICE VESSEL FISHERIES PROTECTION VESSEL FLEET MESSENGER HOSPITAL SHIP MINE CARRIER OILER ORDNANCE SHIP ORDNANCE SLOOP STORESHIP SUBMARINE TENDER TARGET CRAFT TENDER BOMB SCOW DINGHY TORPEDO RECOVERY VESSEL TROOP SHIP VICTUALLER PADDLE STEAMER PATROL VESSEL