The Smacksmen of the North Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'British Small Craft': the Cultural Geographies of Mid-Twentieth

‘British Small Craft’: the cultural geographies of mid-twentieth century technology and display James Lyon Fenner BA MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 Abstract The British Small Craft display, installed in 1963 as part of the Science Museum’s new Sailing Ships Gallery, comprised of a sequence of twenty showcases containing models of British boats—including fishing boats such as luggers, coracles, and cobles— arranged primarily by geographical region. The brainchild of the Keeper William Thomas O’Dea, the nautical themed gallery was complete with an ocean liner deck and bridge mezzanine central display area. It contained marine engines and navigational equipment in addition to the numerous varieties of international historical ship and boat models. Many of the British Small Craft displays included accessory models and landscape settings, with human figures and painted backdrops. The majority of the models were acquired by the museum during the interwar period, with staff actively pursuing model makers and local experts on information, plans and the miniature recreation of numerous regional boat types. Under the curatorship supervision of Geoffrey Swinford Laird Clowes this culminated in the temporary ‘British Fishing Boats’ Exhibition in the summer of 1936. However the earliest models dated back even further with several originating from the Victorian South Kensington Museum collections, appearing in the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883. 1 With the closure and removal of the Shipping Gallery in late 2012, the aim of this project is to produce a reflective historical and cultural geographical account of these British Small Craft displays held within the Science Museum. -

Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021

Document Control Title Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021 Authors T Barnfield; E Johnston; T Dixon; K Saunders; E Siegal Approver(s) V Morgan; J Duffill Telsnig; N Greenwood Owner T Barnfield Revision History Date Author(s) Version Status Reason Approver(s) 19/06/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.1 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A 06/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.2 Draft Internal QA of V Morgan E Johnston Introduction and Part A 07/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 14/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.4 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A JNCC comments 26/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.1 Draft Part B & C N Greenwood E Johnston 29/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.2 Draft Internal QA of Part B N Greenwood E Johnston & C 30/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 05/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.4 Draft Part B & C JNCC N Greenwood E Johnston comments 06/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.0 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston compilation 07/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.1 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston Internal QA 18/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.2 Draft Whole document A Doyle E Johnston JNCC QA 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.3 Draft Whole Document G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.4 Draft Update following G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/01/2021 T Barnfield; V2.0 – 2.4 Draft Updates following NGreenwood; K Saunders; new data availability J Duffill Telsnig T Dixon; E and QA Siegal 01/02/2021 T Barnfield; V2.5 Final Finalise comments Nick Greenwood K Saunders; E and updates Siegal 1 Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2020 Contents Document Control ........................................................................................................... -

An Overview of the Lithostratigraphical Framework for the Quaternary Deposits on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf

An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf Marine Geoscience Programme Research Report RR/11/03 HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are book- marked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub- headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MARINE GEOSCIENCE PROGRAMME The National Grid and other RESEARCH REPORT RR/11/03 Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords Group; Formation; Atlantic margin; North Sea; English Channel; Irish An overview of the lithostratigraphical Sea; Quaternary. Front cover framework for the Quaternary deposits Seismic cross section of the Witch Ground Basin, central North on the United Kingdom continental Sea (BGS 81/04-11); showing flat-lying marine sediments of the Zulu Group incised and overlain shelf by stacked glacial deposits of the Reaper Glacigenic Group. Bibliographical reference STOKER, M S, BALSON, P S, LONG, D, and TAppIN, D R. 2011. An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf. British Geological Survey Research Report, RR/11/03. -

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY to Vibyasxg-ER by Thesi S Submit

EARLY BENGALI PROSE CAREY TO VIBYASXg-ER By Sisirlcumar Baa Thesi s submit ted for the Ph.D. degree in the University of London* June 1963 ProQuest Number: 10731585 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731585 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgment Transliteration Abbreviations; Chapter I. Introduction 1-32 Chapter II. The beginnings of Bengali prose 33-76 Chapter III. William Carey 77-110 Chapter IV. Ramram Basu 110-154 Chapter V. M?ityun;ja^ Bidyalaqikar 154-186 Chapter VI. Rammohan Ray 189-242 Chapter VII. Early Newspapers (1818-1830) 243-268 Chapter VUI.Sarpbad Prabhakar: Ii^varcandra Gupta 269-277 Chapter IX. Tattvabodhi#! Patrika 278-320 Chapter X. Vidyasagar 321-367 Bibli ography 36 8-377 —oOo** ABSTRACT The present thesis examines the growth of Bengali prose from its experimental Beginnings with Carey to its growth into full literary stature in the hands of Vidyasagar. The subject is presented chronologically and covers roughly the first half of the 1 9 th century. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The MARINER's MIRROR the JOURNAL of ~Ht ~Ocitt~ for ~Autical ~Tstarch

The MARINER'S MIRROR THE JOURNAL OF ~ht ~ocitt~ for ~autical ~tstarch. Antiquities. Bibliography. Folklore. Organisation. Architecture. Biography. History. Technology. Art. Equipment. Laws and Customs. &c., &c. Vol. III., No. 3· March, 1913. CONTENTS FOR MARCH, 1913. PAGE PAGE I. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY 4· A SHIP OF HANS BURGKMAIR. FISHING VESSELS. BY R. BY H. H. BRINDLEY • • 8I MORTON NANCE • • . 65 5. DocuMENTS, "THE MARINER's 2. NOTES ON NAVAL NOVELISTS. MIRROUR" (concluded.) CON· BY OLAF HARTELIE •• 7I TRIBUTED BY D. B. SMITH. 8S J. SOME PECULIAR SWEDISH 6. PuBLICATIONS RECEIVED . 86 COAST-DEFENCE VESSELS 7• WORDS AND PHRASES . 87 OF THE PERIOD I]62-I8o8 (concluded.) BY REAR 8. NOTES . • 89 ADMIRAL J. HAGG, ROYAL 9· ANSWERS .. 9I SwEDISH NAVY •• 77 IO. QUERIES .. 94 SOME OLD-TIME SHIP PICTURES. III. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY FISHING VESSELS. BY R. MORTON NANCE. WRITING in his Glossaire Nautique, concerning various ancient pictures of ships of unnamed types that had come under his observation, Jal describes one, not illustrated by him, in terms equivalent to these:- "The work of the engraver, Israel van Meicken (end of the 15th century) includes a ship of handsome appearance; of middling tonnage ; decked ; and bearing aft a small castle that has astern two of a species of turret. Her rounded bow has a stem that rises up with a strong curve inboard. Above the hawseholes and to starboard of the stem is placed the bowsprit, at the end 66 SOME OLD·TIME SHIP PICTURES. of which is fixed a staff terminating in an object that we have seen in no other vessel, and that we can liken only to a many rayed monstrance. -

Space, Submersibles & Superyachts... Space

001 SEA&I 20 COVER_sea&i covers 17/11/10 17:32 Page1 CAMPER & NICHOLSONS INTERNATIONAL www.camperandnicholsons.com WINTER 2011 FOR CONNOISSEURS OF LUXURY TRAVEL A TASTE OF THE GOOD LIFE Culinary sensations FOR CONNOISSEURS OF LUXURY TRAVEL TRAVEL LUXURY OF CONNOISSEURS FOR of the Côte d’Azur SPACE, +10pagesABOARD & ASHORE SUBMERSIBLES & Your comprehensive Caribbean cruising guide SUPERYACHTS... X4 The ultimate travel The best on-board experiences beach clubs SPOTLIGHT ON Odyssey, Illusion & Cloud 9 sea & i Issue 20 Winter 2011 Winter Issue 20 004 SEA&I 20 EDITORIAL_Layout 1 16/11/10 18:34 Page4 INTRODUCES London • 106 New Bond Street - Tel +44 (0)2074 991434 Paris • 60, Rue François Ier - Tel +33 (0)1 42 25 15 41 Cannes • 4, La Croisette - Tel +33 (0)4 97 06 69 70 Saint-Tropez • 3, Rue Allard - Tel +33 (0)4 98 12 62 50 Lyon • 27, Rue Gasparin - Tel +33 (0)4 78 37 31 92 Bordeaux • 29, Cours Georges Clémenceau - Tel +33 (0)5 56 48 21 18 Boutique HUBLOT Cannes • 4, la Croisette - Tel +33 (0)4 93 68 47 88 Boutique HUBLOT St Tropez • Hôtel le Byblos - av. Paul Signac -Tel +33 (0)4 94 56 30 73 Boutique HUBLOT St Tropez • 14, rue François Sibilli, place de la Garonne -Tel +33 (0)4 94 96 58 46 All our brands available on: www.kronometry1999.com LONDON • PARIS • CANNES • MONACO • ST TROPEZ • LYON • BORDEAUX • COURCHEVEL 004 SEA&I 20 EDITORIAL_Layout 1 16/11/10 18:34 Page5 Hublot TV on: www.hublot.com 002 003 SEA&I 20 CONTENTS_Layout 1 16/11/10 18:58 Page2 Contents UP FRONT YACHTING sea& i news Charter choice The latest from CNI and the world of -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Maritime Craft Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: A thesaurus of maritime craft. Date: February 2020 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST AIRCRAFT CATAPULT VESSEL CATAPULT ARMED MERCHANTMAN AMPHIBIOUS VEHICLE BLOCK SHIP BOARDING BOAT CABLE LAYER CRAFT CANOE CATAMARAN COBLE FOYBOAT CORACLE GIG HOVERCRAFT HYDROFOIL LOGBOAT SCHUIT SEWN BOAT SHIPS BOAT DINGHY CUSTOMS AND EXCISE VESSEL COASTGUARD VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER CUSTOMS BOAT PREVENTIVE SERVICE VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER DREDGER BUCKET DREDGER GRAB DREDGER HOPPER DREDGER OYSTER DREDGER SUCTION DREDGER EXPERIMENTAL CRAFT FACTORY SHIP WHALE PROCESSING SHIP FISHING VESSEL BANKER DRIFTER FIVE MAN BOAT HOVELLER LANCASHIRE NOBBY OYSTER DREDGER SEINER SKIFF TERRE NEUVA TRAWLER WHALER WHALE CATCHER GALLEY HOUSE BOAT HOVELLER HULK COAL HULK PRISON HULK 2 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST SHEER HULK STORAGE HULK GRAIN HULK POWDER HULK LAUNCH LEISURE CRAFT CABIN CRAFT CABIN CRUISER DINGHY RACING CRAFT SKIFF YACHT LONG BOAT LUG BOAT MOTOR LAUNCH MULBERRY HARBOUR BOMBARDON INTERMEDIATE PIERHEAD PONTOON PHOENIX CAISSON WHALE UNIT BEETLE UNIT NAVAL SUPPORT VESSEL ADMIRALTY VESSEL ADVICE BOAT BARRAGE BALLOON VESSEL BOOM DEFENCE VESSEL DECOY VESSEL DUMMY WARSHIP Q SHIP DEGAUSSING VESSEL DEPOT SHIP DISTILLING SHIP EXAMINATION SERVICE VESSEL FISHERIES PROTECTION VESSEL FLEET MESSENGER HOSPITAL SHIP MINE CARRIER OILER ORDNANCE SHIP ORDNANCE SLOOP STORESHIP SUBMARINE TENDER TARGET CRAFT TENDER BOMB SCOW DINGHY TORPEDO RECOVERY VESSEL TROOP SHIP VICTUALLER PADDLE STEAMER PATROL VESSEL -

SPC Beche-De-Mer Information Bulletin

ISSN 1025-4943 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BECHE-DE-MER Number 13 — July 2000 INFORMATION BULLETIN Editor and group coordinator: Chantal Conand, Université de La Réunion, Laboratoire de biologie marine, 97715 Saint-Denis Cedex, La Réunion, France. [Fax: +262 938166; E-mail: [email protected]]. Production: Information Section, Marine Resources Division, SPC, B.P. D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia. [Fax: +687 263818; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: http://www.spc.int/coastfish]. Produced with financial assistance from France and Australia. Editorial Dear Readers, Inside this issue This is the 13th issue of the Bulletin. I would like to take this op- portunity to thank all those who have contributed to it and ask Aspects of sea cucumber that you take an active role in its improvement, as many of you broodstock management have already indicated that the Bulletin is useful to you. by A.D. Morgan p. 2 Is the current presentation by section, i.e. 1) New Information, Athyonidium chilensis 2) Correspondence, 3) Publications, satisfactory?: by C. Ravest Presa p. 9 • Which section should be given more space? Sea cucumber fishery in • In the ‘New Information’ section, would you have new infor- the Philippines mation for the columns on ‘In situ spawning observations’ by S. Schoppe p. 10 and ‘Asexual reproduction through fission observations’? Are these columns suitable? Conservation of • The ‘Aquaculture’ column has been continued thanks to the aspidochirotid holothurians in collaboration of S. Battaglene from ICLARM. We regret the the littoral waters of Kenya closure of the Coastal Aquaculture Centre (CAC) Solomon by Y. -

Dogger Bank Complaint

Complaint to the Commission concerning alleged breach of Union legislation Failure to comply with Article 6(1), 6(2) and 6 (3) of Council Directive 92/43/ΕEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna - the Habitats Directive, in relation to the fisheries management measures for the Dutch and UK Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) in the Dogger Bank in the North Sea 24 June 2019 1. Identity and contact details 2. Infringement of EU Law 3. Request for action from the Commission 4. Previous action taken to solve the problem 5. Previous correspondence with EU institutions 6. List any supporting documents/evidence which you could – if requested – send to the Commission 7. Personal data 8. Signatures Annex 1A Dogger Bank H1110 listed typical species reported as bycatch in demersal seining Annex 1B Dogger Bank H1110 listed typical species considered sensitive to bottom disturbance Annex 1C Vulnerable, near threatened, threatened, endangered and critically endangered species known to occur or to have occurred on Dogger Bank (not listed as H1110 typical species by the governments) and observed as bycatch in demersal seining Annex 1D Dogger Bank species known to be typically occurring on the Dogger Bank (however not listed as H1110 typical species by the governments) and reported bycatch Annex 1E Dogger Bank species known to occur or to have typically occurred (however not listed as H1110 typical species by the governments) and considered sensitive to demersal seining Annex 2 Inability to control and enforce with recommended VMS frequency and minimum transit speed Annex 3 The process leading to the proposed management measures of fisheries activities in the Dogger Bank Natura 2000 sites Annex 4 The fisheries industry and nature conservation organisations’ proposals of 2012 Annex 5 Pictures and URLs of demersal seining rope, gear, fisheries, bycatch 1 1. -

Britain's Distant Water Fishing Industry, 1830-1914

BRITAIN'S DISTANT WATER FISHING INDUSTRY, 1830-1914 A STUDY IN TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE being a Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by MICHAEL STUART HAINES APRIL 1998 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 12 i THE THESIS 14 ii CONTEXT 15 iii SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY 19 PART ONE THE ECONOMIC CONTEXT OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 28 CHAPTER 1 THE FISH TRADE 29 i FISH AND THE FISHERIES 29 ii DEVELOPMENT OF THE FISHING INDUSTRY TO 1830 37 iii LATENT DEMAND 44 CHAPTER 2 DISTRIBUTION 50 i INLAND TRANSPORT 50 ii PORT INFRASTRUCTURE 68 iii ACTUAL DEMAND 78 PART TWO TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND FISH PRODUCTION 84 CHAPTER 3 SAIL 85 i TRAWLING 85 ii SMACKS 96 iii ICE 118 iv STEAM AND SMACKS 127 CHAPTER 4 EARLY STEAMERS 134 i EXPERIMENTS AND TUGS 134 ii STEAM FISHING BOATS 143 CHAPTER 5 DEVELOPMENTS AFTER 1894 182 i THE OTTER-TRAWL 182 ii DEMERSAL FISHERIES 188 iii PELAGIC FISHERIES 198 iv MOTORS AND WIRELESSES 211 PART THREE RAMIFICATIONS OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 217 CHAPTER 6 THE INDUSTRY 218 i BUSINESS ORGANIZATION 218 ii HUMAN RESOURCES 233 CHAPTER 7 EXTERNAL FORCES 259 i EUROPEAN FISHING INDUSTRIES 259 ii PERCEPTIONS OF THE FISHERIES 274 iii LEGACY 288 PART FOUR BIBLIOGRAPHY 294 PART FIVE APPENDIX 306 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the National Fishing Heritage Centre, Great Grimsby, for providing funds that enabled completion of this thesis. All the work was done from the University of Hull, and my gratitude is extended to the secretarial staff of the History Department and Kevin Watson for help with various practical matters, together with staff at the Brynmor Jones Library and Graduate Research Institute. -

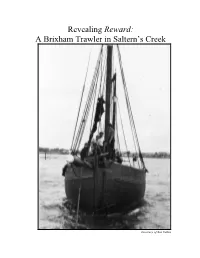

Revealing Reward: a Brixham Trawler in Saltern's Creek

Revealing Reward: A Brixham Trawler in Saltern’s Creek Courtesy of Sue Edden INTRODUCTION “Culture” is a term commonly used today to describe different aspects of a group of people, to describe different beliefs and customs as their ‘culture’ or way of life. But underlying the culture and values of every group of people is heritage: national heritage, local heritage and family heritage. Commonly manifested as artifacts – material objects from the past that still exist today – heritage serves to remind people about their past, where they came from, and who they are. Heritage artifacts therefore contribute to the formation and understanding of identity, whether on a family, local or national level. Worldwide, people surround themselves with objects and artifacts of identity: images of deceased relatives, pictures or objects serving as a reminder of a past experience, and symbols of religion or patriotism. Such artifacts and images are deemed socially important, and may become protected and preserved by institution. How they are valued, however, may differ. Some objects will be conserved or reproduced and placed in a public location to serve as a reminder of the past and social identity, whereas others may be placed in a publicly accessible but strictly regulated location to ensure their survival for future generations. We see some of these objects and sites every time we pass a monument, a historic building, see a flag, or enter a museum. But the objects themselves are merely a tangible and symbolic reminder of heritage; they cannot speak and do not tell their story by merely existing. Rather, their history must be revealed and understood in a broader context to cultivate meaning.