Final Draft Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminist Mobilization and the Abortion Debate in Latin America: Lessons from Argentina

Feminist Mobilization and the Abortion Debate in Latin America: Lessons from Argentina Mariela Daby Reed College [email protected] Mason Moseley West Virginia University [email protected] When Argentine President Mauricio Macri announced in March 2018 that he supported a “responsible and mature” national debate regarding the decriminalization of abortion, it took many by surprise. In a Catholic country with a center-right government, in which public opinion regarding abortion had hardly moved in decades—why would the abortion debate surface in Argentina when it did? Our answer is grounded in the social movements literature, as we argue that the organizational framework necessary for growing the decriminalization movement was already built by an emergent feminist movement of unprecedented scope and influence: Ni Una Menos. Through expanding the movement’s social justice frame from gender violence to encompass abortion rights, feminist social movements were able to change public opinion and expand the scope of debate, making salient an issue that had long been politically untouchable. We marshal evidence from multiple surveys carried out before, during, and after the abortion debate and in-depth interviews to shed light on the sources of abortion rights movements in unlikely contexts. When Argentine President Mauricio Macri announced in March 2018 that he supported a “responsible and mature” national debate regarding the decriminalization of abortion, many were surprised. After all, in 2015 he was the first conservative president elected in Argentina in over a decade, and no debate had emerged under prior center-left governments. Moreover, Argentina is a Catholic country, which has if anything seen an uptick in religiosity over the past decade, and little recent movement in public support for abortion rights preceding Macri’s announcement. -

A CASE for LEGAL ABORTION WATCH the Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina

HUMAN RIGHTS A CASE FOR LEGAL ABORTION WATCH The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina A Case for Legal Abortion The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8462 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8462 A Case for Legal Abortion The Human Cost of Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Rights in Argentina Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 8 To the President of Argentina: ................................................................................................. -

History of Legalization of Abortion in the United States of America in Political and Religious Context and Its Media Presentation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra románských jazyků Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – francouzština Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Vedoucí práce: Ing. BcA. Milan Kohout Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucímu bakalářské práce Ing. BcA. Milanu Kohoutovi za cenné rady a odbornou pomoc, které mi při zpracování poskytl. Dále bych ráda poděkovala svému partnerovi a své rodině za podporu a trpělivost. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Table of contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................1 2 History of abortion.............................................................................................3 2.1 19th Century.......................................................................................................3 -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

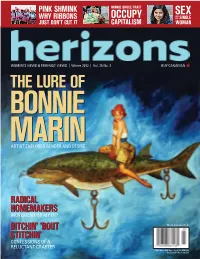

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political. -

Narrating the Nation of Palestine by Nuzhat Abbas

SPECIAL OFFER FOR CONFERENCE DELEGATES See inside for details • Canada $5.95/US $5.95 • Vol. 16 No.4 • Spring 2003 WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS NARRATINGNARRATING THETHE NATIONNATION OFOF PALESTINEPALESTINE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAHLA ABDO WHYWHY DODO LESBIANSLESBIANS BATTER?BATTER? JANICE RISTOCK WANTS TO KNOW THETHE HEARTHEART DOESDOES NOTNOT BENDBEND A CONVERSATION WITH MAKEDA SILVERA NAC NAC. Who’s There? Lisa B. Rundle: Marshalling in the Third Wave Pump up the Volume: Veda Hille, Afua Cooper, Jorane Made in Canada in Made table of contents SPRING 2003 / VOLUME 16 NO. 4 FEATURES NARRATING THE NATION 18 OF PALESTINE Arab feminist Nahla Abdo has written extensively about women and military confrontation and is the founder of a gender research unit within a mental health program in Gaza. A sociology professor at Carleton University, Ms Abdo talks to Herizons about the PLO, Israel, Palestinian women and about her upcoming book, Sexuality, Citizenship and the Nation State: Experiences of Palestinian Women. by Nuzhat Abbas IN CONVERSATION WITH 23 MAKEDA SILVERA Toronto author Makeda Silvera discusses mother- hood, poverty, colonialism and the creative process with author Elizabeth Ruth. “I’ve always questioned the imperial culture’s view of motherhood: mothers are virtuous, mothers are asexual…” by Elizabeth Ruth WHY DO LESBIANS Page 26: Janice Ristock 26 BATTER? A decade ago, Janice Ristock and some colleagues produced a booklet on violence in lesbian relation- NEWS ships. Now the Winnipeg researcher has written a groundbreaking book on the issue. VILLAGERS JOIN CAMPAIGN by Helen Fallding 6 AGAINST FGM A Senegalese women’s organization called Tostan, which means ‘breakthrough’ in the Wolof language, ARTS & LIT sponsors education programs that have influenced the decision of 708 villages to make public declara- CAN LIT tions to abandon the generations-old practice of 32 FICTION female genital mutilation. -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns. -

Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Beyond the Generational Line: An Exploration of Feminist Online Sites and Self-(Re)presentations Yi-lin Yu National Ilan University, Taiwan Abstract This article deals with the feminist generation issue by tracing the transition from generational to non-generational thinking in recent feminist discourse on third-wave feminism. Informed by certain feminist recommendations of affording alternative paradigms in place of the oceanic wave metaphor to describe the rela- tionships between different feminists, this study offers the insights gained from an investigation with three feminist online sites, The F Word, Eminism, and Guerrilla Girls, in which these online feminists have participated in building up a third wave consciousness or a third space site through their engagement in (re)presenting their feminist selves and identities. In developing a both/and third wave con- sciousness, these online feminists have bypassed the dualistic understanding of sec- ond and third wave feminism and reached a cross-generational commonality of adhering to feminist ideology and coalition in cyberspace as a third space. Through a content analysis of their online feminist self-(re)presentations, this pa- per concludes by arguing that they have not only reformulated the concept of third wave feminism but also worked toward a new configuration of third space narratives and subjectivities that sheds light on contemporary feminist thinking about feminist genealogy and history. Key words third-wave feminism, feminist generation, feminist online sites, self-(re)presentation Introduction Recent feminist development of third-wave discourses has been bom- barded with a conundrum regarding generational debates. Although 54 ❙ Yi-lin Yu some feminist scholars are preoccupied with using familial metaphors to depict different feminist generations, others have called forth a rethink- ing of the topic in non-generational terms. -

Her-042 Summer 2008 V21n5.Qxp

WOMEN’S CYCLES (MOTORCYCLES, THAT IS) | TACKLING WIFE ABUSE IN AFGHANISTAN | SUMMER READING GUIDE & MORE! WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Summer 2008 Vol. 22 No. 1 Made in Canada JANE RULES THE BELOVED AUTHOR SHARES HER THOUGHTS ON LIVING, LOVING AND WRITING SIZING UP FASHION JANE RULE 1931–2007 ZERO TOLERANCE FOR SIZE ZERO $6.95 Canada/US Publications TOSHI Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: REAGON PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada FINDING THE GOOD Display until September 15, 2008 WhyIJoinedtheCAW AA Young Young Worker's Worker's Story Story Iusedto ButonceI think my got injured... job was the greatest... Nobody was Things changed when there I joined the CAW... to help... Nowthere'salwayssomeoneinmycorner. Wanna join? Visit: www.caw.ca or call 1-877-495-6551 Email: [email protected] SUMMER 2008 / VOLUME 22 NO. 1 news DOMESTIC ASSAULT IN AFGHANISTAN 6 by Lauryn Oates 8 CAMPAIGN UPDATES MY HEART BELONGS IN THE CAPE 12 by Anat Cohen ITALIAN WOMEN MOBILIZE 13 by Meagan Williams 6: Addressing Domestic Assault in Afghanistan WHAT IF EQUALITY RULED? 14 by Shari Graydon features HOW THE MEDIA KEEPS US HUNG UP 16 ON BODY IMAGE By Shari Graydon JANE RULES 20 It has been said that every child on Galiano learned to swim in Jane Rule and Helen Sonthoff ’s swimming pool. The couple bought their house on Galiano Island as a weekend getaway in the 1970s, fell in love with it and never left. Rule’s legacy is explored in this intimate interview completed in the year before her passing. -

Comprehensive Annotated Listing of All Journals Selected

5. Chang Pilwha. Annotated Listing of All Periodicals Selected7. forISSN Feminist 1225-9276. Periodicals Note: Not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in this issue of Feminist Periodicals. See page 4 for a listing 8. OCLC 33094607. of periodicals in this issue. 9. Alternative Press Index; Current Contents: Social & Behavioral Sciences; IOWA Guide; Social Sciences AFFILIA: JOURNAL OF WOMEN AND SOCIAL WORK Citation Index. 1. 1986. 10. GenderWatch. 2. 4/year. 11. “AJWS is an interdisciplinary journal, publishing articles 3. $129 (indiv. print only), $779 (inst. print only), $716 (inst. pertaining to women’s issues in Asia from a feminist e-access), $795 (inst. combined), $42 (indiv. single print perspective.” issue), $214 (inst. single print issue). 4. Sage Publications, 2455 Teller Rd., Thousand Oaks, CA ASIAN WOMEN 91320 [email: [email protected]] [website: http:// 1. 1995. aff.sagepub.com]. 2. 4/year. 5. Debora Ortega & Noël Busch-Armendariz 3. $60 (student), $80 (indiv.), $120 (inst.). 6. Affilia, Howard University School of Social Work, 601 4. Asian Women, Research Institute of Asian Women, Howard Pl. N.W., Washington DC 20059; book reviews: Sookmyung Women's University, Cheongpa-ro 47gil 100, Dr. Patricia O’Brien [email: [email protected]]. Youngsan-gu, Seoul, 140-742, Korea [email: 7. ISSN 0886-1099. [email protected]] [website: http://riaw.sookmyung. 8. OCLC 12871850. ac.kr]. 9. Criminal justice, family, social science, and women’s 5. So Jin Park studies indexes. Also available on microfilm from Bell & 7. ISSN 1225-925X. Howell Information and Learning, Ann Arbor, MI. 8. OCLC 7673725, 36782501. -

The Stigma of Having an Abortion: Development of a Scale and Characteristics of Women Experiencing Abortion Stigma

The Stigma of Having an Abortion: Development of a Scale and Characteristics of Women Experiencing Abortion Stigma CONTEXT: Although abortion is common in the United States, women who have abortions report signifi cant social By Kate Cockrill, stigma. Currently, there is no standard measure for individual-level abortion stigma, and little is known about the Ushma D. social and demographic characteristics associated with it. Upadhyay, Janet Turan and Diana METHODS: To create a measure of abortion stigma, an initial item pool was generated using abortion story content Greene Foster analysis and refi ned using cognitive interviews. In 2011, the fi nal item pool was used to assess individual-level abor- tion stigma among 627 women at 13 U.S. Planned Parenthood health centers who reported a previous abortion. Factor analysis was conducted on the survey responses to reduce the number of items and to establish scale validity Kate Cockrill is research analyst, and reliability. Diff erences in level of reported abortion stigma were examined with multivariable linear regression. Ushma D. Upadhyay is assistant research RESULTS: Factor analysis revealed a four-factor model for individual-level abortion stigma: worries about judg- scientist, and Diana ment, isolation, self-judgment and community condemnation (Cronbach’s alphas, 0.8–0.9). Catholic and Protestant Greene Foster is women experienced higher levels of stigma than nonreligious women (coeffi cients, 0.23 and 0.18, respectively). On associate professor, all at Advancing the subscales, women with the strongest religious beliefs had higher levels of self-judgment and greater perception New Standards in of community condemnation than only somewhat religious women. -

International Human Rights Law and Abortion in Latin America

Human Rights and Abortion July 2005 International Human Rights Law and Abortion in Latin America Latin America is home to some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the world. While only three countries—Chile, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic—provide no exceptions or extenuating circumstances for the criminal sanctions on abortion, in most countries and jurisdictions, exceptions are provided only when necessary to save the pregnant woman’s life and in certain other narrowly defined circumstances. Even where abortion is not punished by law, women often have severely limited access because of lack of proper regulation and political will. Advancing access to safe and legal abortion can save women’s lives and facilitate women’s equality. Women’s decisions about abortion are not just about their bodies in the abstract, but rather about their human rights relating to personhood, dignity, and privacy more broadly. Continuing barriers to such decisions in Latin America interfere with women’s enjoyment of their rights, and fuel clandestine and unsafe practices, a major cause of maternal mortality in much of the region. Latin American women’s organizations have fought for the right to safe and legal abortion for decades. Increasingly, international human rights law supports their claims. In fact, international human rights legal instruments and interpretations of those instruments by authoritative U.N. expert bodies compel the conclusion that access to safe and legal abortion services is integral to the fulfillment of women’s human rights generally, including their reproductive rights and rights relating to their full and equal personhood. This paper offers (1) a brief overview of the status of abortion legislation in Latin America and (2) an in-depth analysis of international human rights law in this area.