Reform in the Time of Stalin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

416 Entries in the Barents Encyclopedia (In Alphabetical Order)

416 entries in the Barents Encyclopedia (in alphabetical order) As of May 7, 2012 Letters in the leftmost column C mean: S = submitted articles (348) C = articles for which we have contracted authors (68) The entry was found in another encyclopedia / Topic New entry cate- suggested by gory Length C Entry Word [Name] 1-12 of entry Author/-s S Alta V. Tevlina 1 S Nielsen, Jens Petter [email protected] S Alta controversy Saami 3 M Berg, Bård A, [email protected] J. Porsanger S Alymov, Vasilii Kondratevich V.-P. Lehtola 2 S Martyushova, Svetlana, ([email protected]) and Ilicheva, Maria, [email protected] S Alyosha M. Ilicheva 7 S Karelin, Vladimir [email protected] [email protected] S Amundsen, Roald V. Tevlina 2 M Berg, Roald, Stavanger Univ. [email protected] S Andreyev Bay U. Wråkberg 1 S Fiskebeck, Per-Einar Per- [email protected] S Anikiev Island A.N. Davydov 6 S Davydov, Alexander. [email protected] Pomor S Apatity U. Wråkberg 1 S Dyuzhilov, Sergey, [email protected] C Arctic co-operation 8 M Hoel, Alf Håkon [email protected] and Heininen, Lassi [email protected] S Arctic Council M.-O. Olsson 8 S Vaaja, Nina Buvang, [email protected] S Arctic explorations L.-E. Edlund 3 L Wråkberg, Urban, Barents Intsitute, [email protected] S Arctic hunting (previously V. Tevlina 6 M Nielsen, Jens Petter called “Russian and Norwegian [email protected] sea mammal hunting in the Arctic”) S Arctic Ocean, The U. -

Development of Tourism in the Arkhangelsk Area This Article Is Devoted to the Development and Functioning of the Regional Tourism Industry

REGIONAL ECONOMY • The issue theme: TOURISM UDC 338.48(470.11) © V.E. Toskunina © N.N. Shpanova Development of tourism in the Arkhangelsk area This article is devoted to the development and functioning of the regional tourism industry. The main problem of inbound and domestic tourism, the tourism infrastructure state, supply and demand in the tourist market of the Arkhangelsk region are considered in the article. The assessment of historical and cultural factors in the development of regional tourism and regional promotion of tourist products is also given in the article. The tourism branch, regional tourism. Vera E. TOSKUNINA Doctor of Economics, Head of division, Arkhangelsk Scientific Center of the Ural RAS department Natalia N. SHPANOVA Chief searching authority of the Committee on Culture of the Arkhangelsk Region Modern tourism is actively growing sector become comfortable, interesting attracted not of many economies of the world. Despite its only Russians, but also flows of tourists from high tourist potential, Russia is far from ad- other countries. vanced positions on the global tourism market, Available in the Arkhangelsk region of creating mostly visiting flows. As a percentage unique natural complexes and picturesque of gross national product of tourism is less than landscapes with a rich and endemic flora one percent. The main constraint to the devel- and fauna, historical monuments and archi- opment of both domestic and inbound tourism tecture, as well as the culture heritage of the remained steady appreciation the value of travel Russian North can become the basis for the packages. The ratio of price and quality, and development of tourism industry region. -

The Barents Region Volume 11 N-Y

encyclopedia of The Barents Region volume 11 n-y Editor-in-chief MATS-OLOV OLSSON Co-Editors Fredrick Backman, Alexey Golubev, Björn Norlin, Lars Ohlsson Assistant and Graphics Editor Lars Elenius pax forlag a/s, oslo 2016 © pax forlag 2016 cover illustration vol i: the death of willem barentz, oil on canvas by christiaan julius lodewyck portman (1836). national maritime museum, london. cover photo vol ii: russian prirazlomnaya oil rig in the pechora sea, nenets autonomous okrug, operated by gazprom neft. licensed under cc by-sa 4.0, via wikimedia commons. photo: krichevsky. trykk: printed in isbn 978-82-530-3858-2 (vol 1) isbn 978-82-530-3859-9 (vol ii) isbn 978-82-530-3857-5 (vol 1 and vol ii) isbn 978-82-530-3878-0 (the barents region | encyclopedia of the barents region) Image Editor: Anders Alm Cartographer: David Keeping Language Editors: Pat Shrimpton, Umeå, and Matthew Hogg, Semantix, Umeå Board of Advisers Assoc. Prof. Irina A. Chernyakova Prof. Veli Pekka Lehtola Institute of History, Political and Social Giellagas Institute for Sámi Studies Sciences, Petrozavodsk State University, University of Oulu, Finland Russian Federation Assoc. Prof. Lyubov A. Maksimova Assoc. Prof. Alexander N. Davydov Institute of History and Law, Institute of Ecological Problems of the North Syktyvkar State University, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ural Branch, Russian Federation Arkhangelsk, Russian Federation Assoc. Prof. Jelena Porsanger Prof. Lars-Erik Edlund Sámi University College, Department of Language Studies, Kautokeino, Norway Umeå University, Sweden Prof. Helge Salvesen Prof. Lars Elenius Department of History and Religious Studies, Department of Business Administration, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Technology and Social Sciences, Tromsø, Norway Luleå University of Technology, Sweden Prof. -

Reform in the Time of Stalin: Nikita Khrushchev and the Fate of the Russian Peasantry” Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Auri C

REFORM IN THE TIME OF STALIN: NIKITA KHRUSHCHEV AND THE FATE OF THE RUSSIAN PEASANTRY by Auri C. Berg A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Auri Berg (2012) Abstract “Reform in the Time of Stalin: Nikita Khrushchev and the Fate of the Russian Peasantry” Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Auri C. Berg Graduate Department of History University of Toronto “Reform in the Time of Stalin” is an exploration of a little-known, but highly significant chapter from the last years of the Stalin era. Between 1949 and 1951, Nikita Khrushchev attempted to carry out a radical reform of collective farms, an event that served as a turning point in the history of rural Russia and could be justifiably labeled “the second collectivization.” Through the prism of James Scott's concept of “high modernism,” this study examines the issue of reform under Stalin, demonstrating the political, economic, and social context in which the top leadership struggled to reform what had become an unworkable agricultural system. The dissertation draws on sources from party and state archives in Moscow, Kiev and Arkhangelsk, as well as central and regional newspapers and unpublished memoirs. To lay the background, the dissertation first explores the failed attempt by the Soviet Union to replace the traditional Russian commune with larger, rationally organized farms during the course of collectivization in the early 1930s. The subsequent two chapters are focused on the origins of the reform campaign: first in post-war Ukraine, where Nikita Khrushchev had considerable independence; and subsequently in Moscow, where high-level political rivalries and institutional competition undermined his efforts. -

Economic Potential of the Arkhangelsk Region

ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF THE ARKHANGELSK REGION. TOURISTIC BUSINESS IN THE NORTH Oleg Semkov Arkhangelsk CCI, president ARKHANGELSK REGION TOADY •Square – 589 000 km2 •Population – 1,2 mln •Capital city – Arkhangelsk (pop. 350 000) •Gross regional product in 2011 – RUR 384 bln •Average payroll income in 2011 – RUR 24 000 GROSS REGIONAL PRODUCT •Forestry and timber (17,1%) •Transport and logistics (15,4%) 2/3 GRP in 5 •Trade (17,3%) major sectors •Construction (13,2%) •Shipbuilding (5,0%). } TIMBER INDUSTRY Production in the region •pulp, paper and paperboard •lumber •glulam •houses Allowable cut – 23,8 mln m3 TIMBER INDUSTRY Major businesses in pulp-and- paper industry: •Kotlas PPM •Arkhangelsk PPM •Solombala PPM Production of Arkhangelsk timber processing industry is being exported to 79 countries of the world MINING Share in proved reserves of minerals in RF: Diamonds Bauxites Gypsum Zink Lead 20% 18% 1% 3% 2% •Diamond extraction in 2011 – 0.5 mln carat •“Knauf” – mining of gypsum in the Arkhangelsk region •Proven reserves of basalts – 4,6 bln t MINING Arctic, the «pantry» of Russia 90% of the hydrocarbons are located in the Arctic, including 70% – on the shelf of Barents and Kara seas FISHING INDUSTRY Fishing volume in 2011 – 151 000 tons Main perspectives – creating of new fish processing facilities. TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS •Multiprofile seaport •The Northern railway •International airport •M-8 federal highway, Arkhangelsk-Moscow •Administration of the Northern Sea Route •Terminal & logistics center, JSC “Russian railways” (perspective) «BELKOMUR» PROJECT •Total length – 1155 km •Investments – RUR 176 bln. •Private investments into related projects – RUR 442 bln. •Public-private partnership terms •Cargo turnover of the «Northern link» by 2020 – 20 mln. -

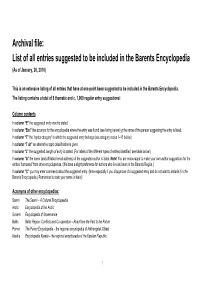

List of All Entries Suggested to Be Included in the Barents Encyclopedia (As of January, 26, 2010)

Archival file: List of all entries suggested to be included in the Barents Encyclopedia (As of January, 26, 2010) This is an extensive listing of all entries that have at one point been suggested to be included in the Barents Encyclopedia. The listing contains a total of 8 thematic and c. 1,000 regular entry suggestions! Column contents In column “E” the suggested entry word is stated. In column “Enc” the acronym for the encyclopedia where the entry was found (see listing below) or the name of the person suggesting the entry is listed. In column “T” the “topics category” to which the suggested entry belongs (see category codes 1–13 below); In column “T alt” an alternative topic classification is given. In column “L” the suggested Length of entry is stated. (For labels of the different types of entries identified, see table below!) In column “A” the name (and affiliation/email address) of the suggested author is listed. Note! You are encouraged to make your own author suggestions for the entries “borrowed” from other encyclopedias. (We have a slight preference for authors who live and work in the Barents Region.) In column “C” you may enter comments about the suggested entry. (Note especially if you disapprove of a suggested entry and do not want to include it in the Barents Encyclopedia.) Remember to state your name (initials)! Acronyms of other encyclopedias: Saami The Saami – A Cultural Encyclopaedia Arctic Encyclopedia of the Arctic Govern Encyclopedia of Governance Baltic Baltic Region: Conflicts and Co-operation – Road from the Past to the Future Pomor The Pomor Encyclopedia – the regional encyclopedia of Arkhangelsk Oblast Karelia Encyclopedia Karelia – the regional encyclopedia of the Karelian Republic 1 Total no. -

«Visit» Russian North

99, Voskresenskaya St., Arkhangelsk, 163071 Russia, (+78182) 20-20-99, [email protected] 95/2, Northern Dvina emb., Arkhangelsk, 163061 Russia, (+78182) 28-62-40, [email protected] Travel to Russian North Here, under heavy north conditions, where survival becomes a crucial need, people go «Visit» Russian to know outworld, themselves and their companions. Еvery step to the North made by man gives North him new fit of energy and inspiration. ―North opens face of our soul what let us behave without stereotypes and complexes‖. (Oleg Kodola) Welcome Tourist agency ―Visit‖ is regional tour operator, registered in Federal List of Russian Tour Operators, offers different services: - reservation in hotel and touristic complexes of Arkhangelsk and region; - organization of conferences, seminars, incentive-tours; - transport service; - Russian visas for foreigners; - reservation and sale of tickets. - excursion programs for group and individuals on request. - highly professional guides and interpreters. The whole Arkhangelsk-Region is for you! 99, Voskresenskaya St., Arkhangelsk, 163071 Russia, (+78182) 20-20-99, [email protected] 95/2, Northern Dvina emb., Arkhangelsk, 163061 Russia, (+78182) 28-62-40, [email protected] Dear Sirs! We are pleased to introduce Tourist Agency “VISIT” Arkhangelsk, Russia. Letter of General Director We hope the tourist companies and individuals looking for getting acquainted with Russian North find the following information interesting. Tourist agency "Visit" is a professional tourist services company possessing extensive local knowledge, expertise and resources, specialized on design and implementation of events, activities, tours, transportation and program logistics. Founded in 1989, each year we improve our technology. Nowadays tourist agency "Visit" is the leading company of tourist business in Arkhangelsk region (North-West of Russia). -

Framed Architecture in History

Session 8 [Thursday 2nd period 1.5 hours - Hall A] Artistic aspects of wood use and design (continued) Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 1 Speakers Speaker: Jianju Luo Topic: Introduction of Wood Aesthetics and its Application in Daily Life Speaker: Kitazawa Hideta Topic: Enjoyment of Traditional Japanese Wood Carving Speaker: Olga G Sevan Topic: Traditional and Modern House Paintings and Arts of Wood in Everyday Life Speaker: Guixang Wang Topic: Impression Comparison and Understanding: Chinese Wood-Framed Architecture in History Proceedings of the Art and Joy of Wood conference, 19-22 October 2011, Bangalore, India 2 Introduction of Wood Aesthetics and its Application in Daily Life Jianju Luo, Ye Ping and Luo Fan1 Abstract After a brief discussion on principle and exploiting technology of wood esthetics, application possibilities of wood esthetics in daily life were demonstrated with concrete examples in this paper. On a macro-level, taking annual rings as an example, the esthetical principle lies in the fact that the patterns of annual rings conform perfectly to “Change and Unity”, a basic rule in esthetics. On a micro-level, taking vessels as an example, the esthetical principle lies in the extremely abundant wood structural patterns formed on the wood surfaces by pores, pits, spiral thickenings, perforations, tyloses and gum blocks contained in vessel cavities. Some of the esthetical elements of macro- or micro-level, can directly form esthetical patterns of high value on wood surfaces, and some of them can be extracted and used as source materials for re-creation of esthetical patterns. -

Chamber of Commerce and Industry

CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY Business cooperation with the Arkhangelsk region, Russia International trade and investments Arkhangelsk region on the map Arkhangelsk region Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 Arkhangelsk region on the map R U S S I A Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 General information Population – approx. 1 200 000 people Area – 587,400 km2 (226,800 sq. mi) Federal district – Northwestern Administrative center – Arkhangelsk Main river – Northern Dvina Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 Timezone MSK Largest higher education institutions: Northern State Medical University (NSMU), M.V. Lomonosov Northern Arctic Federal University (M.V. Lomonosov NArFU) Washed by the White sea, the Barents sea, the Kara sea Has common borders with The Republic of Karelia , Murmansk , Vologda region , Kirov region , Republic of Komi , the Tyumen region Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 GRP structure Agriculture Public administration and Fishing, aquaculture associated services Natural resources Real estate operations Manufacture Finance Transport and communications Power energy Building HoReCA Retail and services Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 Export structure Fuel 2018 2% 0% 4% 1% Timber products 8% Commodities and gem stones 12% 43% Cellulose Fish and seafood 15% Ferrous metals 15% Mechanical equipment, computers Optics, devices and medtech Arkhangelsk region CCI, 2018 Import structure Products of animal origin 2018 2% 1% Chemical industry products 9% 7% Plastics, rubber and gum 9% Textile Stone, ceramic and glass products 8% Machines, equipment and apparatus