Royal Army Medical ,Corps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

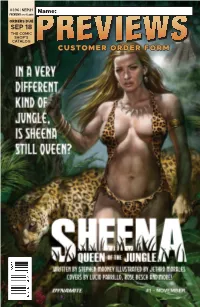

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present

UGC MRP - COMICS BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present UGC MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT F.NO. 5-131/2014 (HRP) DT.15.08.2015 Principal Investigator: Aneeta Rajendran, Gargi College, University of Delhi UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Acknowledgements This work was made possible due to funding from the UGC in the form of a Major Research Project grant. The Principal Investigator would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Project Fellow, Ms. Shreya Sangai, in drafting this report as well as for her hard work on the Project through its tenure. Opportunities for academic discussion made available by colleagues through formal and informal means have been invaluable both within the college, and in the larger space of the University as well as in the form of conferences, symposia and seminars that have invited, heard and published parts of this work. Warmest gratitude is due to the Principal, and to colleagues in both the teaching and non-teaching staff at Gargi College, for their support throughout the tenure of the project: without their continued help, this work could not have materialized. Finally, much gratitude to Mithuraaj for his sustained support, and to all friends and family members who stepped in to help in so many ways. 1 UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Project Report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. Scope and Objectives 3 2. Summary of Findings 3 2. Outcomes and Objectives Attained 4 3. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire to Be”

Ro yThomas’’ BXa-Ttrta ilor od usinary Comiics Fanziine DARK NIGHTS & STEEL $6.95 IN THE GOLDEN & SILVER AGES In the USA No. 59 June 2006 SUYDAM • ADAMS • MOLDOFF SIEGEL • PLASTINO PLUS: MANNING • MATERA & MORE!!! Batman TM & ©2006 DC Comics Vol. 3, No. 59 / June 2006 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Contents Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Writer/Editorial: Dark Nights & Steel . 2 Production Assistant Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire To Be” . 3 Eric Nolen-Weathington Interview with the artist of Cholly and Flytrap and Marvel Zombies covers, by Renee Witterstaetter. Cover Painting “Maybe I Was Just Loyal” . 14 Arthur Suydam 1950s/60s Batman artist Shelly Moldoff tells Shel Dorf about Bob Kane & other phenomena. And Special Thanks to: “My Attitude Was, They’re Not Bosses, They’re Editors” . 25 Neal Adams Richard Martines Golden/Silver Age Superman artist Al Plastino talks to Jim Kealy & Eddy Zeno about his long Heidi Amash Fran Matera and illustrious career. Michael Ambrose Sheldon Moldoff Bill Bailey Frank Motler Jerry Siegel’s European Comics! . 36 Tim Barnes Brian K. Morris When Superman’s co-creator fought for truth, justice, and the European way—by Alberto Becattini. Dennis Beaulieu Karl Nelson Alberto Becattini Jerry Ordway “If You Can’t Improve Something 200%, Then Go With The Thing John Benson Jake Oster That You Have” . 40 Dominic Bongo Joe Petrilak Modern legend Neal Adams on the late 1960s at DC Comics. -

Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 Free

FREE CHARLEYS WAR: 1 AUGUST-17 OCTOBER 1916 PDF Pat Mills,Joe Colquhoun | 112 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781840239294 | English | London, United Kingdom Charley's War - Wikipedia This book picks up where the last left off with two main story arcs. The first follows the technological innovation theme from the earlier book and examines the impact of the introduction of the first British tanks on the battle. The second half sees the Germans reacting to this new development in the only way they can — increased ferocity, brutality and dirty tactics — flying in the face Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the gentlemanly conduct of previous confrontations run by unsuitable aristocrats. The other major theme running through this book is the regularlity with which the British army is willing to shoot and torture its own men, for anything from basic insubordination through to falling asleep on duty. As before, the waste of human life presented Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the comic is poignant and more than a little shocking, not least of all because the story is reprinted from a publication aimed at young boys interested in the glamour of soldiering. Charley loses friends quicker than he can make them and the horror of it all turns this social, caring individual away from forming any bonds with his colleagues in the trenches because the likelihood of losing them is so high. When all the English look like bedraggled waifs and the Germans like uniformed barbarians, it Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 us away from the true nature World War I — an entire generation of men grinding one another into mince. -

War Comics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

War comics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia War comics is a genre of comic books that gained popularity in English-speaking countries following War comics World War II. Contents 1 History 1.1 American war comics 1.2 End of the Silver Age 1.3 British war comics 2 Reprints 3 See also 4 References 5 Further reading 6 External links History American war comics Battlefield Action #67 (March 1981). Cover at by Pat Masulli and Rocco Mastroserio[1] Shortly after the birth of the modern comic book in the mid- to late 1930s, comics publishers began including stories of wartime adventures in the multi-genre This topic covers comics that fall under the military omnibus titles then popular as a format. Even prior to the fiction genre. U.S. involvement in World War II, comic books such as Publishers Quality Comics Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941) depicted DC Comics superheroes fighting Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Marvel Comics Golden Age publisher Quality Comics debuted its title Charlton Comics Blackhawk in 1944; the title was published more or less Publications Blackhawk continuously until the mid-1980s. Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos In the post-World War II era, comic books devoted Sgt. Rock solely to war stories began appearing, and gained G.I. Combat popularity the United States and Canada through the 1950s and even during the Vietnam War. The titles Commando Comics tended to concentrate on US military depictions, Creators Harvey Kurtzman generally in World War II, the Korean War or the Robert Kanigher Vietnam War. Most publishers produced anthologies; Joe Kubert industry giant DC Comics' war comics included such John Severin long-running titles as All-American Men of War, Our Russ Heath Army at War, Our Fighting Forces, and Star Spangled War Stories. -

Chambers Pardon My French!

Chambers Pardon my French! CHAMBERS An imprint of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 7 Hopetoun Crescent, Edinburgh, EH7 4AY Chambers Harrap is an Hachette UK company © Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 2009 Chambers® is a registered trademark of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd First published by Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 2009 Previously published as Harrap’s Pardon My French! in 1998 Second edition published 2003 Third edition published 2007 Database right Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd (makers) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0550 10536 3 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 We have made every effort to mark as such all words which we believe to be trademarks. We should also like to make it clear that the presence of a word in the dictionary, whether marked or unmarked, in no way affects its legal status as a trademark. www.chambers.co.uk Designed -

40Th Anniversary Primer

200040TH ANNIVERSARY AD PRIMER 40TH INSERT.indd 1 07/02/2017 15:28 JUDGE DREDD FACT-FILE First appearance: 2000 AD Prog 2 (1977) Created by: John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Judge Dredd is a totalitarian cop in Mega- Blue in a sprawling ensemble-led police an awful lot of blood in his time. City One, the vast, crime-ridden American procedural about Dredd cleaning up crime East Coast megalopolis of over 72 million and corruption in the deadly Sector 301. With stories such as A History of Violence people set 122 years in the future. Judges and Button Man, plus your hard-boiled possess draconian powers that make them Mega-City Undercover Vols. 1-3 action heroes like Dredd and One-Eyed judge, jury, and executioner – allowing them Get to know the dark underbelly of policing Jack, your love of crime fiction is obvious. to summarily execute criminals or arrest Mega-City One with Justice Department’s Has this grown over the years? What citizens for the smallest of crimes. undercover division. Includes Andy Diggle writers have influenced you? and Jock’s smooth operator Lenny Zero, and Created by John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra Rob Williams, Henry Flint, Rufus Dayglo and JW: I go through phases. Over the past few in 1977, Dredd is 2000 AD’s longest- D’Israeli’s gritty Low Life. years I have read a lot of crime fiction, running character. Part dystopian science enjoyed some, disliked much. I wouldn’t like fiction, part satirical black comedy, part DREDD: Urban Warfare to pick any prose writer out as an influence. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries.