Architecture, Violence and Sensation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Abc Warriors - the Mek Files 2: 2

ABC WARRIORS - THE MEK FILES 2: 2 Author: Pat Mills, Kev Walker Number of Pages: 208 pages Published Date: 11 Sep 2014 Publisher: Rebellion Publication Country: Oxford, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781781082591 DOWNLOAD: ABC WARRIORS - THE MEK FILES 2: 2 Contact us. My Library. Affiliate System. How to Sell on DriveThruComics. Create Content for your Favorite Games. About Us. Privacy Policy. Our Latest Newsletter. Product Reviews. As the droids Hammerstein, Mongrol, Joe Pineapples, Deadlock and Blackblood all relate their memories of the war, old mysteries are revealed and ancient grudges are rekindled! Warriors epic! Date This week Last week Past month 2 months 3 months 6 months 1 year 2 years Pre Pre Pre Pre Pre s s s s s s Search Advanced. Issue ST. There are serious postal delays due to the coronavirus and the build up to Christmas. The Volgan War volumes 01 and 02 are available as individual collections, as are volumes 03 and 04, to be combined for Mek Files 05 at some later stage. The Slings and Arrows Graphic Novel Guide doesn't care where you've been, where you're going or where you're located. Mars, the far future. War droids created for a conflict that ended centuries ago, the A. Warriors are resistant to Atomic, Bacterial and Chemical …. This hardback collection continues the new series collecting up the complete ABC Warriors stores in a highly collectible hardback format. But when Bedlam's son is murdered by the ranchers, he leads his tribe into an attack. Since the ranchers are armed, it seems like a slaughter — but Deadlock and Blackblood had secretly infiltrated the ranchers' camp, disarming their guns. -

Abc Warriors - the Mek Files 2: 2 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ABC WARRIORS - THE MEK FILES 2: 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pat Mills,Kev Walker | 208 pages | 11 Sep 2014 | Rebellion | 9781781082591 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom ABC Warriors - The Mek Files 2: 2 PDF Book The human colonists ravaged Mars and the sentient planet has had enough! JavaScript must be enabled to use this site. See other items More Now meet Mongrol! Starting from the strips' very beginning, this hardback collection is a start of a new series collecting the complete A. Volume 3 - 1st printing. We're featuring millions of their reader ratings on our book pages to help you find your new favourite book. This for me was formative years reading, and the artwork is still drop dead gorgeous. Release date NZ September 11th, Friend Reviews. Percy Bell added it Jun 11, Volume 4 - 1st printing. A P Corrigan rated it it was amazing Sep 11, Add to Trolley. Contact details. Jan 19, Tom Evans rated it really liked it. Martian natives have taken up the cause and are fighting back for their world. You can then select photos, audio, video, documents or anything else you want to send. Coronavirus delivery updates. Warriors Accept all Manage Cookies. Lists with This Book. Home Learning. Popular Features. He is best known for creating AD and playing a major part in the development of Judge Dredd. Pat Mills. Available Stock Add to want list This item is not in stock. The file can be downloaded at any time and as often as you need it. Error rating book. Sort order. For other issues perhaps you did not like a product or it did not live up to expectations , we are happy to refund all costs but require the buyer to pay the return postage cost. -

Tharg's Nerve Centre

THARG’S NERVE CENTRE IN THIS PROG JUDGE DREDD // WAR BUDS Mega-City One, 2139 AD. Home to over 72 million citizens, this urban hell is situated along the east coast of post-apocalyptic North America. Unemployment is rife, and crime is rampant. Only the Judges — empowered to dispense instant justice — can stop total anarchy. Toughest of them all is JUDGE DREDD — he is the Law! Now, former members of the Apocalypse Squad are fleeing the city, having freed a friend... Judge Dredd created by John Wagner & Carlos Ezquerra THE ALIENIST // INHUMAN NATURES England, 1908. Madelyn Vespertine, an Edwardian woman of unknown age and origin, BORAG THUNGG, EARTHLETS! investigates strange events of an occult nature, accompanied by Professor Sebastian I am The Mighty Tharg, galactic godhead at the Wetherall. Little do those that meet the pair know that the Professor is actually an actor helm of this award-winning SF anthology! called Reginald Briggs, a stooge covering for the fact that Madelyn is not human. Now, the We’re barrelling towards the explosive finales of all sinister Professor Praetorius is aiming to stop a dimensional infection from spreading... the current Thrills next prog to make way for a brand- The Alienist created by Gordon Rennie, Emma Beeby & Eoin Coveney new line-up to commence in the truly scrotnig Prog 2050. Last week I spoke of the Rogue Trooper story GREYSUIT // FOUL PLAY by James Robinson and Leonardo Manco that you’ll London, 2014. John Blake is a GREYSUIT, a Delta-Class assassin working for a branch of find within its pages, but what else will be joining it? British Intelligence. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Geek Syndicate Hi All, Barry and Dave Here.!

Geek Syndicate Hi all, Barry and Dave Here.! Welcome to the Geek Syndicate app. We hope to add more exclusive extras and stuff as we get use to the technology but in the meantime I hope you will enjoy this example (taken from our website) of some of the extras we want to have. I am Sherlock! Not being entirely embedded in the genre, the BBC’s recent adaptation of Sherlock Holmes was, I regret to say, my first experience of the London deducer (I assume I don’t count Basil The Great Mouse Detective?). I obviously had my preconceived ideas; deer-stalker hat, pipe, drugs, smoggy Victorian London blah, blah, blah. The slightly archaic boy’s-own feel I get from just holding one of Conan Doyle’s books has never attracted me to actually open it, let alone choose to spend my time watching one of the myriad of adaptations available. But, having also recently ‘found’ Doctor Who, I found myself eagerly awaiting each of the ‘Moffatiss’ episodes with bated breath. I am aware this post is a little late in the game, but it only really hit me today just what a profound effect the show has had on me. I was simply walking down the street when a very muscular chap crossed to walk in front of me. Instantly my womanly judgement mode kicked in as I could see he had gone to the effort of cutting one trouser leg higher that the other. I have often heard tell the tales of such fashion stylings but had never actually seen it for myself, and here was quite a scary looking gentleman sporting a custom designed Adidas version. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

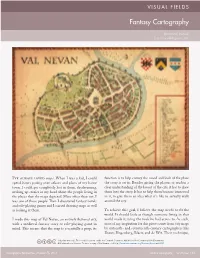

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Colour Your Own Judge Dredd Cover!

ColoUr your own Judge Dredd Cover! © Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd You’re the art droid! Create your own Judge Dredd adventure below! © Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd QUIZ PAGES WORD SEARCH! STEALING GRAFFITI fifteen years Judge Cadets spend If you want to give ccipital lobes to LITTERING COFFEE refining their o your brainbulb a f crime! Scan this spot any kind o ARSON MUTANTS real cosmic crunch, wordsearch with your own sneak- try solving these peepers to find these ten things PIRACY SWEARING puzzles with one eye outlawed in Mega-City One and prove closed while running you have the observational power- JIMPING SUGAR an Andalusian skills required to enforce THE LAW. (impersonating dressage course! a Judge) CBLRDYWHYAJCQOMSP UTHXgHJSPGPOPUNBW LITTErINGFPFZJXCB UEZSFBaZPJWFTTQDs ITKVYHEfZMVEMVHwJ HZQVQVNHfXCEHReSF LRNYVRIHUiKXTaALY sASTEALINGtCrYFAD tMATDGPWQGSiRCIZR nCMILUYSYRnQFaWCW aFZBTSSLTgAZaRSON TWRSTSRNHOYMDIGOK UYPFHGACFPQNJPSMD MSOaXgnipmijNXWaa © Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd Dredd is so zapped-up on SPOT THE DIFFERENCE! irresistible umpty-candy that he’s seeing double! Find 10 differences between these two saccharine scenes and help jounce the Judge from a serious sugar surge. MATCH THE THRILL-SUCKERS! Two Thrill-Suckers – parasitic energy eaters from the planet ZRAG - have snuck between these very pages by hiding among my ultra- D collectable limited- B edition-variant Joy- Sniffer(tm) dolls! Can you limber up your face-orbs and find the two identical infiltrators among the mismatched models before they slurp up every speck of scintillating storytelling…. permanently? C A E A & E ARE THE SAME - ZAP ‘EM NOW! ‘EM ZAP - SAME THE ARE E & A THRILL-SUCKERS: THE MATCH CANDY. EMPTY CALLED NOW IS CANDY UMPTY 10. -

Five Goes Mad in Stockbridge Fifth Doctor Peter Davison Chats About the New Season

ISSUE #8 OCTOBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JUDGE DREDD Writer David Bishop on taking another shot at ‘Old Stony Face’ DOCTOR WHO Scribe George Mann on Romana’s latest jaunt FIVE GOES MAD IN STOCKBRIDGE FIFTH DOCTOR PETER DAVISON CHATS ABOUT THE NEW SEASON PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Hello. More Vortex! Can you believe it? Of course studio session to make sure everyone is happy and that you can, you’re reading this. Now, if I sound a bit everything is running on time. And he has to do all those hyper here, it’s because there’s an incredibly busy time CD Extras interviews. coming up for Big Finish in October. We’ve already started recording the next season of Eighth Doctor What will I be doing? Well, I shall be writing a grand adventures, but on top of that there are more Lost finale for the Eighth Doctor season, doing the sound Stories to come, along with the Sixth Doctor and Jamie design for our three Sherlock Holmes releases, and adventures, the return of Tegan, Holmes and the Ripper writing a brand new audio series for Big Finish, which and more Companion Chronicles than you can shake may or may not get made one day! More news on that a perigosto stick at! So we’ll be in the studio for pretty story later, as they say… much the whole month. I say ‘we’… I actually mean ‘David Richardson’. He’s our man on the spot, at every Nick Briggs – executive producer SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical Bernice Summerfield A short story collection by Robert Shearman Secret Histories Rob Shearman is probably best known as a writer for Doctor This year’s Bernice Summerfield book is a short Who, reintroducing the Daleks for its BAFTA winning first stories collection, Secret Histories, a series of series, in an episode nominated for a Hugo Award. -

Judge Dredd Megazine, #1 to 412

Judge Dredd stories appearing in the Judge Dredd Megazine, #1 to 412 Note: Artists whose names appear after an “&” are colourists; artists appearing after “and” are inkers or other co-artists. Volume One The Boy Who Thought He Art: Barry Kitson & Robin Boutell Wasn't Dated: 26/12/92 America Issue: 19 Issues: 1-7 Episodes: 1 Warhog Episodes: 7 Pages: 9 Issue: 19 Pages: 62 Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Episodes: 1 Script: John Wagner Art: Russell Fox & Gina Hart Pages: 9 Art: Colin MacNeil Dated: 4/92 Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Dated: 10/90 to 4/91 Art: Xuasus I Was A Teenage Mutant Ninja Dated: 9/1/93 Beyond Our Kenny Priest Killer Issues: 1-3 Issue: 20 Resyk Man Episodes: 3 Episodes: 1 Issue: 20 Pages: 26 Pages: 10 Episodes: 1 Script: John Wagner Script: Alan Grant Pages: 9 Art: Cam Kennedy Art: Sam Keith Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Dated: 10/90 to 12/90 Dated: 5/92 Art: John Hicklenton Note: Sequel to The Art Of Kenny Dated: 23/1/93 Who? in 2000 AD progs 477-479. Volume Two Deathmask Midnite's Children Texas City Sting Issue: 21 Issues: 1-5 Issues: 1-3 Episodes: 1 Episodes: 5 Episodes: 3 Pages: 9 Pages: 48 Pages: 28 Script: John Wagner Script: Alan Grant Script: John Wagner Art: Xuasus Art: Jim Baikie Art: Yan Shimony & Gina Hart Dated: 6/2/93 Dated: 10/90 to 2/91 Dated: 2/5/92 to 30/5/92 Note: First appearance of Deputy Mechanismo Returns I Singe the Body Electric Chief Judge Honus of Texas City.