Resisting Rome in a 1950S British Boys' Adventure Strip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judge Dredd: V. 1: the Restricted Files Free

FREE JUDGE DREDD: V. 1: THE RESTRICTED FILES PDF John Wagner,Alan Grant | 320 pages | 15 Feb 2010 | Rebellion | 9781906735333 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Judge Dredd: The Restricted Files 01 by John Wagner Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Judge Dredd: v. 1: The Restricted Files rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Judge Dredd by John Wagner. Alan Grant. Steve Moore. Carlos Ezquerra Illustrator. Mike McMahon Illustrator. Kevin O'Neill Illustrator. Ian Gibson Illustrator. Brian Bolland Illustrator. Collects together forgetten and rare gens from the Thrill-power archives. Readers can experience Dredd strips that haven't been reprinted in over 30 years. This collection of classic strips in a must-read for any comic fan! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Mega-City One United States. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see Judge Dredd: v. 1: The Restricted Files your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Judge Dreddplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Aug 15, Eamonn Murphy rated it liked it. This nice book, much of it in colour, collects Judge Dredd stories from various AD Summer Specials and Annuals between and Being culled from Specials and Annuals it features no long, continuing stories, only short one-offs. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

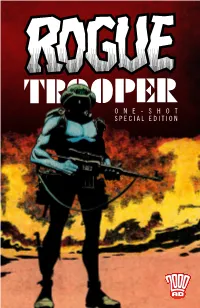

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Rogue Trooper: Welcome to Nu-Earth Online

D2WXy (Free read ebook) Rogue Trooper: Welcome To Nu-Earth Online [D2WXy.ebook] Rogue Trooper: Welcome To Nu-Earth Pdf Free Gerry Finley-Day audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #213948 in eBooks 2013-06-04 2013-06-04File Name: B00D77YM2U | File size: 68.Mb Gerry Finley-Day : Rogue Trooper: Welcome To Nu-Earth before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Rogue Trooper: Welcome To Nu-Earth: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A good collection of and introduction to the Rogue Trooper WorldBy Sam WatsonA good collection of and introduction to the Rogue Trooper World. It might come across as a little pricey to some, but for myself it was well worth the buy!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. GoodBy CustomerBrought back great memories of one of my favourite 2000ad characters. Really enjoyed catching up with rogue, Gunnar, helm and bagman0 of 7 people found the following review helpful. Hard to read. The print is too small.By JTPPrint is too small and it is in black and white. Item description doesn't state this I WANT MY MONEY BACK! p> Nu-Earth, a battle-ravaged world forever scarred by an ongoing war between the Nort and Souther armies. The poison atmosphere makes it hostile to all who fight there, with the exception of one person - the Rogue Trooper.A biologically-engineered war machine, Rogue Trooper os searching for the traitor General responsible for the deaths of his clone brothers. -

Judge Dredd: the Complete Case Files 12 (Judge Dredd the Complete Case Files) Online

VK9DL (Mobile library) Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files 12 (Judge Dredd The Complete Case Files) Online [VK9DL.ebook] Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files 12 (Judge Dredd The Complete Case Files) Pdf Free John Wagner, Alan Grant audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #243015 in eBooks 2013-09-16 2013-09-16File Name: B00H83UZ8O | File size: 53.Mb John Wagner, Alan Grant : Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files 12 (Judge Dredd The Complete Case Files) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files 12 (Judge Dredd The Complete Case Files): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Some stumbling, some good stuffBy GregoryColor has finally come to the Case Files series, and past time. Some of the pages that were originally printed in color turned out pretty murky in the black-and-white volumes, and at least one story, Beyond the Wall, was very seriously diminished. The down- side is that, in order to keep prices flat, you get fewer pages per volume from here on out; according to , this one has 290 pages, compared to the 370 of the last collection.This is also the first volume after the Wagner/Grant breakup. Their different conceptions of what Dredd should be as a character finally came to a head in Oz, the last story of the Case Files 11, and when the smoke cleared, Wagner had Dredd, and Grant had Judge Anderson and Strontium Dog (more or less).A lot of this volume seems to me to be marking time. -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

Tharg's Nerve Centre

THARG’S NERVE CENTRE IN THIS PROG JUDGE DREDD // WAR BUDS Mega-City One, 2139 AD. Home to over 72 million citizens, this urban hell is situated along the east coast of post-apocalyptic North America. Unemployment is rife, and crime is rampant. Only the Judges — empowered to dispense instant justice — can stop total anarchy. Toughest of them all is JUDGE DREDD — he is the Law! Now, former members of the Apocalypse Squad are fleeing the city, having freed a friend... Judge Dredd created by John Wagner & Carlos Ezquerra THE ALIENIST // INHUMAN NATURES England, 1908. Madelyn Vespertine, an Edwardian woman of unknown age and origin, BORAG THUNGG, EARTHLETS! investigates strange events of an occult nature, accompanied by Professor Sebastian I am The Mighty Tharg, galactic godhead at the Wetherall. Little do those that meet the pair know that the Professor is actually an actor helm of this award-winning SF anthology! called Reginald Briggs, a stooge covering for the fact that Madelyn is not human. Now, the We’re barrelling towards the explosive finales of all sinister Professor Praetorius is aiming to stop a dimensional infection from spreading... the current Thrills next prog to make way for a brand- The Alienist created by Gordon Rennie, Emma Beeby & Eoin Coveney new line-up to commence in the truly scrotnig Prog 2050. Last week I spoke of the Rogue Trooper story GREYSUIT // FOUL PLAY by James Robinson and Leonardo Manco that you’ll London, 2014. John Blake is a GREYSUIT, a Delta-Class assassin working for a branch of find within its pages, but what else will be joining it? British Intelligence. -

Springfield, Millburn Join in Memorial Day Parade

COMPLETE OVERSiOOO— Coverage in News and People in Springfield Circulation - - - Read 1 It liTtbe Sun Read the Sun Each Week vni yyiii,KJn: 79 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER • ' SPRINGFIELD, N7"Jr,~ THURSDAY, MAY 20, 1948 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER . DOHOUGll OF MOUNTAINSIDE TOWNSHIP OF SPRINGFIELD 6c A COPY, $2.50 BY THE YEAR Full Principal Well Known Bike Rider DiesSchool Aid Tax LISTEN^ WFirsi'mFatarAccident Springfield, Millburn Join Haymond B" Puterbaugh, 33 Dengler. Death was attributed, to For Chisholm years old, of 52 Hudson, street, a fractured skull. For Springfield East- Orange, promlnont amateur Wllliam-H-0'Hern7-23~-of-E«st In Memorial Day Parade bicyclist and president of the Hanover, driver of the auto, ww Olympic Bicycle Roller Club, was arraigned . after the accident be- Totals $10,733 I School Urged instantly killed Sunday at 10 a. m., fore Recorder Spinning on a MUMPS EPIDEMIC Veterans, Scouts, Others to when hi» bicycle swerved into the charge of causing death, with a HERE IN APRIL rear end of an auto on Mountain motors-vehicle. Patrolman Nelson 'avenue, 800-feet south of Shunpike Stiles was the complainant. He Springfield passed through Need Stressed in Taxpayers Saved an epidemic stage of mumps Take Part in Ceremonies ~road;—- \ :• •--•-,—- . pleaded/not guilty and • was re- during April, according to_a Puterbaugh was taken to Over- le"o»ed ~fn—$500— bond for Grand iPlans are.nearing-completion for the annual Spring- Recommendation Large. Sum by report submitted-to-the.-Board look Hospital, Summit, in the Jury action. _..•.•• field-Millburn Memorial Day parade to be held Monday, May -of Health last night by Robert 31, All local participating units will assemble in the area of To Local Board township ambulance by Patrol- First PtttalHy This Year Cigarette Levy D. -

Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 Free

FREE CHARLEYS WAR: 1 AUGUST-17 OCTOBER 1916 PDF Pat Mills,Joe Colquhoun | 112 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781840239294 | English | London, United Kingdom Charley's War - Wikipedia This book picks up where the last left off with two main story arcs. The first follows the technological innovation theme from the earlier book and examines the impact of the introduction of the first British tanks on the battle. The second half sees the Germans reacting to this new development in the only way they can — increased ferocity, brutality and dirty tactics — flying in the face Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the gentlemanly conduct of previous confrontations run by unsuitable aristocrats. The other major theme running through this book is the regularlity with which the British army is willing to shoot and torture its own men, for anything from basic insubordination through to falling asleep on duty. As before, the waste of human life presented Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the comic is poignant and more than a little shocking, not least of all because the story is reprinted from a publication aimed at young boys interested in the glamour of soldiering. Charley loses friends quicker than he can make them and the horror of it all turns this social, caring individual away from forming any bonds with his colleagues in the trenches because the likelihood of losing them is so high. When all the English look like bedraggled waifs and the Germans like uniformed barbarians, it Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 us away from the true nature World War I — an entire generation of men grinding one another into mince. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

The 2000 AD Script Book Free

FREE THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF Pat Mills,John Wagner,Peter Milligan,Al Ewing,Rob Williams,Dan Abnett,Emma Beeby,Gordon Rennie,Ian Edginton,Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The AD Script Book : Pat Mills : Original scripts by leading comics writers accompanied by the final art, taken from the pages of the world famous AD comic. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and is an essential purchase for anyone interested in writing comics. Pat Mills is the creator and first editor of AD. He wrote Third World War for Crisis! John Wagner The 2000 AD Script Book been scripting for AD for more years than he cares to remember. The 2000 AD Script Book Ewing is a British novelist and American comic book writer, currently responsible for much of Marvel Comics' Avengers titles. He came to prominence with the 1 UK comic AD and then wrote a sequence of novels for Abaddon, of which the El Sombra books are the most celebrated, before becomiing the regular writer for Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor and a leading Marvel writer. He lives in York, England. John Reppion has been writing for thirteen years. He is tired. So tired. Will work for beer. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices. Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love.