Saint Patrick in the Isle of Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

William Cashen's Manx Folk-Lore

WI LLI AM CAS HEN WILLIAM CASHEN’S MANX FOLK-LORE william cashen 1 william cashen’s manx folk-lore 2 WILLIAM CASHEN’S MANX FOLK-LORE 1 BY WILLIAM CASHEN 2 Edited by Stephen Miller Chiollagh Books 2005 This electronic edition first published in 2005 by Chiollagh Books 26 Central Drive Onchan Isle of Man British Isles IM3 1EU Contact by email only: [email protected] Originally published in 1912 © 2005 Chiollagh Books All Rights Reserved isbn 1-898613-19-2 CONTENTS 1 Introduction i * “THAT GRAND OLD SALT BILL CASHEN” 1. Cashin: A Character Sketch (1896) 1 2. William Cashin: Died June 3rd 1912 (1912) 2 3. The Old Custodian: An Appreciation (1912) 9 * “loyalty to Peel” 4. “Madgeyn y Gliass” (“Madges of the South”) 13 5. Letter from Sophia Morrison to S.K. Broadbent (1912) 15 6. Wm. Cashen’s Manx Folk Lore (1913) 16 * CUSTOMS AND SUPERSTITIONS OF THE MANX FISHERMEN 7. Superstitions of the Manx Fishermen (1895) 21 8. Customs of the Manx Fishermen (1896) 24 * CONTENTS * william cashen’s manx folk-lore Preface 31 Introduction (by Sophia Morrison) 33 ɪ. Home Life of the Manx 39 ɪɪ. Fairies, Bugganes, Giants and Ghosts 45 ɪɪɪ. Fishing 49 ɪv. History and Legends 59 v. Songs, Sayings, and Riddles 61 1 INTRODUCTION In Easter 1913, J.R. Moore, who had emigrated from Lonan to New Zealand,1 wrote to William Cubbon: I get an occasional letter from my dear Friend Miss Morrison of Peel from whom I have received Mr J.J. Kneens Direct Method, Mr Faraghers Aesops Fables, Dr Clague’s Reminiscences in which I[’]m greatly disappointed. -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

Corkish Spouses

Family History, Volume IV Corkish - Spouse 10 - 1 Corkish Spouses Margery Bell married Henry Corkish on the 18th of August, 1771, at Rushen. Continued from 1.8.6 and see 10.2.1 below. Catherine Harrison was the second wife of Christopher Corkish when they married on the 31st of October, 1837, at Rushen. Continued from 10.4.1 and see 10.3 below. Isabella Simpson was the second wife of William Corkish, 4th September, 1841, at Santan. Continued from 1.9.8 and see 10.29.7 below. Margaret Crennell married John James Corkish on the 20th of December, 1853, at Bride. Continued from 5.3.1.1 and see 10.20.2 below. Margaret Gelling married Isaac Corkish on the 30th of April, 1859, at Patrick. Continued from 7.2.1 and see 10.18.7 below. Margaret Ann Taylor married Thomas Corkish on the 14th of August, 1892, at Maughold. Continued from 4.13.9 and see 10.52.110.49.1 below. Margaret Ann Crellin married William Henry Corkish on the 27th of January, 1897, at Braddan. Continued from 9.8.1 and see 10.5 below. Aaron Kennaugh married Edith Corkish on the 26th of May, 1898, at Patrick Isabella Margaret Kewley married John Henry Corkish on the 11th of June, 1898, at Bride. 10.1 John Bell—1725 continued from 1.8.6 10.1.1 John Bell (2077) ws born ca 1725. He married Bahee Bridson on the 2nd of December, 1746, at Malew. See 10.2 for details of his descendants. 10.1.2 Bahee Bridson (2078) was born ca 1725. -

The Sophia Morrison & Josephine Kermode

THE SOPHIA MORRISON & JOSEPHINE KERMODE COLLECTION OF MANX FOLK SONGS A PRELIMINARY VIEW One of the difficulties of seeing Sophia Morrison and Josephine Kermode as song collectors is that there are no notebooks full of folk songs nor, say, a bundle of sheets pinned or grouped together to conveniently stand out as being the Morrison and Kermode Collection. There is not, for instance, the four tune books that make up the Clague Collection nor the bound transcript of the Gill brothers collecting to hold reassuringly in the hand. Instead, we have loose sheets scattered amongst her personal papers, others to be found in the hands of Kermode, her close friend and it is argued her fellow-collector. Then there are the song texts published in 1905 in Manx Proverbs and Sayings. And then, remarkably, her sound recordings made with the phonograph of the Manx Language Society purchased in 1904, the cylinders now lost. Morrison stands out as one of the pioneers in Europe in putting the phonograph to use in recording vernacular song culture. It is clear, however, that Morrison’s papers and effects have suffered a considerable loss despite them being in family hands until their eventual deposit in the then Manx Museum Library. One always reads through them with a sense that there was once more— considerably more—and so then they can present us at this date only with a partial view of her activities and that any sense or assessment of her achievements as a collector will ever understate her work. She was active as a folklorist, folk song collector, a promotor of the Manx language, and a Pan Celtic enthusiast of note. -

Marown Parish Commissioners Barrantee Skeerey Marooney 24 April 2008 – Marown Methodist Church Hall, Crosby

Election for Marown Parish Commissioners Barrantee Skeerey Marooney 24 April 2008 – Marown Methodist Church Hall, Crosby Dear fellow Marown resident My name is PAUL CRAINE. I have been privileged to represent you on Marown Commissioners for the past year. I was “elected unopposed” in March 2007. It didn’t feel at all like democracy in action so I am pleased that the people of Marown will have a chance to vote on 24th April and I invite you to vote for me. I am 52 years old and was born and grew up in the Isle of Man. I first lived in Marown when my parents moved here in the 1970s. I am married to Ann, we have two daughters and we have lived in Ballagarey for almost 8 years. I work in the Department of Education as the education adviser to the Island’s five secondary schools, a post I took up in 1999 after a successful 20-year career in teaching. In addition to being one of your Commissioners I have, until recently been Chairman of the Island Games Association of Mann. I am currently Secretary of the Island’s Christian Aid Committee as well as a member of the Methodist Synod. What have I done in 12 months as a Marown Commissioner? I have attended every monthly meeting of the Commissioners. I have also represented Marown Commissioners on the Western District Housing Committee and on the Municipal Association. In turn I have represented the Municipal Association on the Richmond Hill Consultative Committee which monitors the work of the Energy from Waste Plant. -

QUAYLE, George Martyn Personal

QUAYLE, George Martyn Personal BornBorn:: 6th6th February 1959,1959, Isle of Man ParentsParents:: Late George Douglas Quayle, CP Marown and Elaine Evelyn (née(née Corrin) of Glenlough Farm. EducationEducation:: Marown Primary School, Douglas High School (Ballakermeen and St Ninian's) FamilyFamily:: Unmarried Career:Career: Isle of Man Government Civil Service 1975-76;1975-76; Isle of Man Farmers Ltd, Agricultural and Horticultural Merchants 1976-2002,1976-2002, serving as Managing Director 1986-1986- 2002 and Company Secretary 2000-022000-02 Public Service:Service: Former ChairmanChairman:: Isle of Man Tourism Visitor Development Partnership,Partnership, Tourism Management Committee,Committee, Ardwhallin Trust Outdoor Pursuits Centre,Centre, Young Farmers'Farmers’ European Conference,Conference, Isle of Man Federation of Young Farmers' Clubs,Clubs, United Kingdom Young Farmers'Farmers’ Ambassadors, Rushen Round Table and former National CouncillorCouncillor of Round Tables of Great Britain and IrelandIreland;; Patron:Patron: Kirk Braddan Millennium Hall Appeal;Appeal; President:President: European International Farm Youth Exchange Alumni Association, Glenfaba Chorale; Vice-President:-President: Central Young Farmers' Club, Marown Football Club, CrosbyCrosby Silver Band, Marown Royal Ploughing Match Society;Society; Member:Member: Marown Parish Church RoyalRoyal British Legion (Braddan and Marown Branch), Young Farmers' Ambassadors, Manx National Farmers' Union, Rushen 41 Club; Life Member:Member: World Manx Association Interests:Interests: -

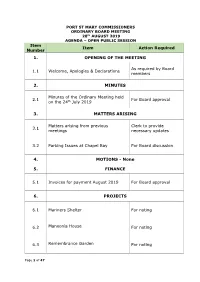

Item Number Item Action Required 1

PORT ST MARY COMMISSIONERS ORDINARY BOARD MEETING 28th AUGUST 2019 AGENDA – OPEN PUBLIC SESSION Item Item Action Required Number 1. OPENING OF THE MEETING As required by Board 1.1 Welcome, Apologies & Declarations members 2. MINUTES Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting held 2.1 For Board approval on the 24th July 2019 3. MATTERS ARISING Matters arising from previous Clerk to provide 3.1 meetings necessary updates 3.2 Parking Issues at Chapel Bay For Board discussion 4. MOTIONS - None 5. FINANCE 5.1 Invoices for payment August 2019 For Board approval 6. PROJECTS 6.1 Mariners Shelter For noting 6.2 Manxonia House For noting 6.3 Remembrance Garden For noting Page 1 of 47 6.4 Skate Park For noting 6.5 Public Conveniences For noting 6.6 Traffic Consultations For noting 6.7 Happy Valley Moved to private 6.8 Boat Park For noting 6.9 Reduction in Board numbers For noting 6.10 Jetty Repair For noting 6.11 Bay Queen Exhibition For noting 7. PUBLIC CORRESPONDENCE – None 7.1 Chief Minister’s Tree Planting Initiative For Board discussion Complimentary correspondence from 7.2 For Board discussion resident re wild flowers 7.3 2nd Supplemental list For noting Notification of Beach Road proposed 7.4 For noting closure 8. PUBLIC CONSULTATIONS Reform of the planning system - Public 8.1 consultation in relation to secondary For Board discussion legislation Page 2 of 47 Proposed Consumer Protection from 8.2 Unfair Trading Regulations 2019 - For Board discussion Consultation Tynwald Commissioner for For Board discussion & 8.3 Administration – Stakeholder response Consultation 9. -

IOMFHS Members' Interests Index 2017-2020

IOMFHS Members’ Interests Index 2017-2021 Updated: 9 Sep 2021 Please see the relevant journal edition for more details in each case. Surnames Dates Locations Member Journal Allen 1903 08/9643 2021.Feb Armstrong 1879-1936 Foxdale,Douglas 05/4043 2018.Nov Bailey 1814-1852 Braddan 08/9158 2017.Nov Ball 1881-1947 Maughold 02/1403 2021.Feb Banks 1761-1846 Braddan 08/9615 2020.May Barker 1825-1897 IOM & USA 09/8478 2017.May Barton 1844-1883 Lancs, Peel 08/8561 2018.May Bayle 1920-2001 Douglas 06/6236 2019.Nov Bayley 1861-2007 08/9632 2020.Aug Beal 09/8476 2017.May Beck ~1862-1919 Braddan,Douglas 09/8577 2018.Nov Beniston Leicestershire 08/9582 2019.Aug Beniston c.1856- Leicestershire 08/9582 2020.May Blanchard 1867 Liverpool 08/8567 2018.Aug Blanchard 1901-1976 08/9632 2020.Aug Boddagh 08/9647 2021.Jun Bonnyman ~1763-1825 02/1389 2018.Aug Bowling ~1888 Douglas 08/9638 2020.Nov Boyd 08/9647 2021.Jun Boyd ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Boyd(Mc) 1788 Malew 02/1385 2018.Feb Boyde ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Bradley -1885 Douglas 09/8228 2020.May Breakwell -1763 06/5616 2020.Aug Brew c.1800 Lonan 09/8491 2018.May Brew Lezayre 06/6187 2018.May Brew ~1811 08/9566 2019.May Brew 08/9662 2021.Jun Bridson 1803-1884 Ramsey 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson 1783 Douglas 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson c.1618 Ballakew 08/9555 2018.May Bridson 1881 Malew 08/8569 2018.Nov Bridson 1892-1989 Braddan,Massachusetts 09/8496 2018.Nov Bridson 1861 on Castletown, Douglas 08/8574 2018.Nov Bridson ~1787-1812 Braddan 09/8521 2019.Nov Bridson 1884 Malew 06/6255 2020.Feb Bridson 1523- 08/9626 -

St Patrick in the Isle of Man: a Folklore Sampler

STEPHEN MILLER SAINT PATRICK IN THE ISLE OF MAN A FOLKLORE SAMPLER CHIOLLAGH BOOKS FOR CULTURE VANNIN 2019 SAINT PATRICK IN THE ISLAND OF MAN A FOLKLORE SAMPLER * contents 1 The Coming of Saint Patrick 1 2 The Traditionary Ballad 7 3 Saint Patrick and Manannan 8 4 Saint Patrick and the Devil 9 5 Saint Patrick’s Curse on Ballafreer 11 6 Saint Patrick’s Bed at Ballafreer 12 7 Saint Patrick and Pudding 15 8 Saint Patrick’s Chair 16 9 Saint Patrick’s Footprints 27 10 Saint Patrick’s Well: Peel 32 11 Saint Patrick’s Well: Maughold 34 12 Saint Patrick’s Well: A Manx Scrapbook (1929) 36 13 Saint Patrick’s Well: Manx Calendar Customs (1942) 38 14 Saint Patrick in Proverbs 39 15 Saint Patrick in Prayers 41 16 Saint Patrick’s Day Hiring Fair 42 * SAINT PATRICK IN THE ISLE OF MAN 1 The Isle of Man Weekly Times ran this quiz in its issue for 15 March 1957, and for those who either do not know the answers nor can read upside down, they are: (1) Mull Hill near the Sound. (2) On slopes of Slieu Chiarn, Marown (3) Peel Castle is built on it. (4) Ballafreer. In the Isle of Man, St Patrick left behind more of a mark than this, and so the numer of questions could be easily extended. A parish is named after him, there is a church dedicated to his memory, a number of keeils bear his name, as do wells, two of which mark where he first landed on his horse. -

Publicindex Latest-19221.Pdf

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF CHARITIES Registered in the Isle of Man under the Charities Registration and Regulation Act 2019 No. Charity Objects Correspondence address Email address Website Date Registered To advance the protection of the environment by encouraging innovation as to methods of safe disposal of plastics and as to 29-31 Athol Street, Douglas, Isle 1269 A LIFE LESS PLASTIC reduction in their use; by raising public awareness of the [email protected] www.alifelessplastic.org 08 Jan 2019 of Man, IM1 1LB environmental impact of plastics; and by doing anything ancillary to or similar to the above. To raise money to provide financial assistance for parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man whose finances determine they are unable to pay costs themselves. The financial assistance given will be to provide full/part payment towards travel and accommodation costs to and from UK hospitals, purchase of items to help with physical/mental wellbeing and care in the home, Belmont, Maine Road, Port Erin, 1114 A LITTLE PIECE OF HOPE headstones, plaques and funeral costs for children and gestational [email protected] 29 Oct 2012 Isle of Man, IM9 6LQ aged to 16 years. For young adults aged 16-21 years who are supported by their parents with no necessary health/life insurance in place, financial assistance will also be looked at under the same rules. To provide a free service to parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man helping with funeral arrangements of deceased children To help physically or mentally handicapped children or young Department of Education, 560 A W CLAGUE DECD persons whose needs are made known to the Isle of Man Hamilton House, Peel Road, 1992 Department of Education Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 5EZ Particularly for the purpose of abandoned and orphaned children of Romania.