Mild Revolution’: the Politics of Ealing Studios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

Title Page Table

RE-IMAGINING THE JEWELLED ISLE: ENGLAND AND CROSS-MEDIA PROJECTS IN THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY By Chu-Jiun Alice Chuang Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2010 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Mark Wollaeger Professor Paul Young Professor Vereen Bell Professor Marina MacKay ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Vanderbilt University Graduate School and English Department for the financial support they have provided these five years and for the Dissertation Enhancement Grant, without which much of the archival research in my dissertation would not have been possible. I am also indebted to the British Film Institute and its dedicated librarians for guiding me through the special collections archives and allowing me to spend a week examining the Carol Reed Papers and the London Film Production Papers. I would also like to thank the members of my Dissertation Committee for their support and advice through the dissertation process. In particular, I am grateful to my dissertation director, Professor Mark Wollaeger, for all the time he put in to reading and commenting on my work—his invaluable guidance throughout this process is much appreciated. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………… ii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………...…. 1 Defining the Nation: Empire, World War II, and English Culture………………………. 3 Photography, Radio, Film, and Modernism………………………………………………8 Chapters Overview……………………………………………………………………….13 PART 1 II. RADIO, CINEMA, AND THE BODILY SENSORIUM IN VIRGINIA WOOLF’S THE YEARS……………………………………………………………………………………. 18 ! Woolf and Late Modernism……………………………………………………………. 18 ! Modernism and Media…………………………………………………………………. 21 ! Woolf’s Participatory Communalism…………………………………………………. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

The Grierson Effect

Copyright material – 9781844575398 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Notes on Contributors . ix Introduction . 1 Zoë Druick and Deane Williams 1 John Grierson and the United States . 13 Stephen Charbonneau 2 John Grierson and Russian Cinema: An Uneasy Dialogue . 29 Julia Vassilieva 3 To Play The Part That Was in Fact His/Her Own . 43 Brian Winston 4 Translating Grierson: Japan . 59 Abé Markus Nornes 5 A Social Poetics of Documentary: Grierson and the Scandinavian Documentary Tradition . 79 Ib Bondebjerg 6 The Griersonian Influence and Its Challenges: Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong (1939–73) . 93 Ian Aitken 7 Grierson in Canada . 105 Zoë Druick 8 Imperial Relations with Polynesian Romantics: The John Grierson Effect in New Zealand . 121 Simon Sigley 9 The Grierson Cinema: Australia . 139 Deane Williams 10 John Grierson in India: The Films Division under the Influence? . 153 Camille Deprez Copyright material – 9781844575398 11 Grierson in Ireland . 169 Jerry White 12 White Fathers Hear Dark Voices? John Grierson and British Colonial Africa at the End of Empire . 187 Martin Stollery 13 Grierson, Afrikaner Nationalism and South Africa . 209 Keyan G. Tomaselli 14 Grierson and Latin America: Encounters, Dialogues and Legacies . 223 Mariano Mestman and María Luisa Ortega Select Bibliography . 239 Appendix: John Grierson Biographical Timeline . 245 Index . 249 Copyright material – 9781844575398 Introduction Zoë Druick and Deane Williams Documentary is cheap: it is, on all considerations of public accountancy, safe. If it fails for the theatres it may, by manipulation, be accommodated non-theatrically in one of half a dozen ways. Moreover, by reason of its cheapness, it permits a maximum amount of production and a maximum amount of directorial training against the future, on a limited sum. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson

23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson Save 0 Filmography Show less 1971 Creatures the World Forgot Special Effects 1969 Desert Journey Special Effects 1969 Autokill Special Effects 1966 The Heroes of Telemark [Special Effects] 1965 The Secret of Blood Island Special Effects 1965 The Brigand of Kandahar Special Effects 1964 The Long Ships Special Effects 1964 The Gorgon Special Effects 1962 In Search of the Castaways Special Effects 1960 The Brides of Dracula Special Effects 1959 Too Many Crooks [Special Processes] 1959 North West Frontier Special Effects 1959 The Hound of the Baskervilles Special Effects 1959 Ferry to Hong Kong Special Effects 1958 Dracula Special Effects 1957 The Steel Bayonet Special Effects 1957 Campbell's Kingdom Special Effects 1956 The Ladykillers Special Effects 1956 House of Secrets Special Processes (uncredited) 1956 Reach for the Sky Models (uncredited) 1955 Out of the Clouds Special Effects 1955 The Ship That Died of Shame Special Effects 1955 The Night My Number Came Up Special Effects 1955 Touch and Go Special Effects 1954 The Love Lottery Special Effects 1954 The 'Maggie' Special Effects https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 1/2 23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI 1953 The Cruel Sea Special Effects 1953 The Titfield Thunderbolt Special Effects 1952 His Excellency Special Effects 1952 Mandy [Special Effects] 1952 I Believe in You Special Effects (uncredited) 1952 The Gentle Gunman Special Effects 1952 Secret People Special Effects 1951 Pool of London Special Effects 1951 The Man in the White Suit Special Effects 1951 The Lavender Hill Mob Special Effects 1950 Cage of Gold Special Effects 1950 Dance Hall Special Effects 1950 The Magnet Special Effects 1949 Kind Hearts and Coronets Special Effects 1949 Train of Events Special Effects 1949 Whisky Galore! Special Effects 1948 Scott of the Antarctic Special Effects 1947 The October Man [Stage Effects] [Model Miniatures] 1947 Black Narcissus [Synthetic Pictorial Effects] https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 2/2. -

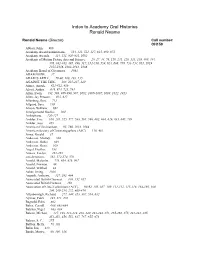

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.