Tortoise Identification Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Husbandry and Captive Breeding of the Bated by Slow Or Indirect Shipping

I\IJtIlD AND T'II'LT' Iil1,TUKTS j r8- I.r I o, ee+,, JilJilill fl:{:r;,i,,'J,:*,1;l: dehydration, and thermal exposure of improper or protracted warehousing on either or both sides of the Atlantic, exacer- Husbandry and Captive Breeding of the bated by slow or indirect shipping. These situations may also Parrot-Beaked Tortoise, have provided a dramatic stress-related increase in parasite Homopus areolatus or bacterial loads, or rendered pathogens more virulent, thereby adversely affecting the health and immunity levels Jnuns E. BIRZYKI of the tortoises. With this in mind, 6 field-collected tortoises | (3 project 530 l,{orth Park Roacl, Lct Grctnge Pcrrk, Illinois 60525 USA males, 3 females) used in this were airfreighted directly from South Africa to fully operational indoor cap- The range of the parrot-beaked tortoise, Hontopus tive facilities in the USA. A number of surplus captive areolatus, is restricted to the Cape Province in South Africa specirnens (7) were also available, and these were included (Loveridge and Williams, 1957; Branch, 1989). It follows in the study group. the coastline of the Indian Ocean from East London in the Materials ancl MethocLr. - Two habitat enclosures mea- east, around the Cape of Good Hope along the Atlantic surin-e 7 x2 feet (2.1 x 0.6 m) were constructed of plywood Ocean, north to about Clanwilliam. This ran-qe is bordered in and each housed two males and either four or five females. the northeast by the very arid Great Karoo, an area receiving These were enclosed on all sides, save for the front, which less than 250 mm of rain annually, and in the north by the had sliding ..elass doors. -

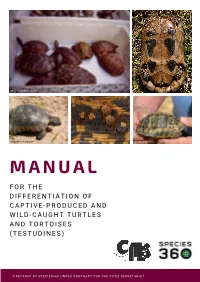

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Turtles #1 Among All Species in Race to Extinction

Turtles #1 among all Species in Race to Extinction Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation and Colleagues Ramp Up Awareness Efforts After Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble Report Published Washington, DC (February 24, 2011)―Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC), an Top 25 Most Endangered Tortoises and inclusive partnership dedicated to the conservation of Freshwater Turtles at Extremely High Risk the herpetofauna--reptiles and amphibians--and their of Extinction habitats, is calling for more education about turtle Arranged in general and approximate conservation after the Turtle Conservation Coalition descending order of extinction risk announced this week their Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble 1. Pinta/Abingdon Island Giant Tortoise report. PARC initiated a year-long awareness 2. Red River/Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle campaign to drive attention to the plight of turtles, now the fastest disappearing species group on the planet. 3. Yunnan Box Turtle 4. Northern River Terrapin 5. Burmese Roofed Turtle Trouble for Turtles 6. Zhou’s Box Turtle The Turtle Conservation Coalition has highlighted the 7. McCord’s Box Turtle Top 25 most endangered turtle and tortoise species 8. Yellow-headed Box Turtle every four years since 2003. This year the list included 9. Chinese Three-striped Box Turtle/Golden more species than previous years, expanding the list Coin Turtle from a Top 25 to Top 25+. According to the report, 10. Ploughshare Tortoise/Angonoka between 48 and 54% of all turtles and tortoises are 11. Burmese Star Tortoise considered threatened, an estimate confirmed by the 12. Roti Island/Timor Snake-necked Turtle Red List of the International Union for the 13. -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys Pardalis

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys pardalis Class: Sauropsida Order: Chelonia Family: Testudinidae Characteristics: The leopard tortoise is the fourth largest tortoise species in the world. They get their name from their color pattern on the elevated carapace, or shell. The rings of yellow, tan, and brown resemble leopard spots. These tortoises can reach up to two feet in length and weigh up to 80 pounds (National Zoo). Tortoises lack ears, but can sense vibrations from the surrounding environment. They also lack teeth, but have a sharp beak for tearing into foods. These tortoises are well adapted to hot, arid areas (Maryland Zoo). Range & Habitat: Leopard tortoises are found in Behavior: sub-Saharan Africa, from Sudan Leopard tortoises are considered crepuscular. They try to seek shade and south to the Cape Province of avoid activity during the hottest parts of the day in the savannah sun. They South Africa. They are often found spend most of their time grazing on grasses (Maryland Zoo). If threatened, in savannah grasslands (Reptile a leopard tortoise has been known to poop on its predator. Males compete Database). for females during mating season by pushing each other until one is flipped upside down (National Zoo). Reproduction: Females will dig a nest about one foot deep and will lay up to 30 eggs in the nest. The eggs will hatch about 18 months after they are laid. Neither the male nor female are involved in parenting the offspring. Diet: Wild: grasses and succulents (prickly pear cactus) Zoo: mixed greens, sweet potato, apple, carrot, tomato, oranges, clovite, Lifespan: over 100 years in hay, tortoise pellet. -

Leopard Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH LEOPARD TORTOISE CARE Leopard tortoises are large tortoises, originating from the grasslands of sub-Saharan Africa. It is essential not to underestimate the space and resources needed to look after these tortoises which will grow very large. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. As large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. Wood chip based substrates should never be used for this reason. -

Descriptions of Some A.Frican Tortoises

A"nals aftlte Natal Museum. Vol. VI, 1)(1ft 3 DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME AFRICAN TORTOISES. 46 1 Descriptions of some A.frican Tortoises. By John II C\\'itt. With P lates XXXVI-XXXVIII, and 5 Text. fi gul·es. CONTENTS. P elusios s inuatus s inu n.t us Smith J(j2 P elus ios s illu atus zuluensis H elQift 462 P ell1si os ni g r ica. ns n igricnns DonllC/. 4(\3 Pelus ios ni g ri can s castanoides SIIUS)1. n . 4(13 Peil1si os nigr icn.ns ca.stan e us Schw. 464 P elus ios nigricans rh odesianus H ellJi tt 465 Kinixys hellian!} Gray -I n? Kinixys nogll ey i Lataste ·HiS Kin ixys s pekii Gray. 469 Kinixys be lliana. zombensis sllbsp. '11. ·WO Kinixys belJin.nn. zulllon sis subs)1 . n. 47 1 Kinixys n. ustra lis 8p. It. 477 Kinixys da.rlingi Blgr. 4, 1 Kini xys jordn.ni sp . n . 482 Kinixys yonn gi ap. n. 4SG Kini xys lo bn.ts ia na Pou'er 488 H omopus WaMb. ..HHi Pseudomopus g. n . ·Hlli T estlld o L . 4!)H Neotestlldo g. n. 50" 462 JOHN HEWI'IT. THE material dealt wi th in this revi ew has bef' 1l derived from varioll s sources. A good portion of it is contained in the Albany Musemu, and for the loan of specimens I am especia.lly indebted to the Mu seums at Pretoria, Kimberley and Pietermaritzburg. It, may be .aid that the. present study again illustrates the fact t.hat the closer a group of organisms is studied and the wider the area from which they are obt.ained, the greater is the difficnlty ill formulating any clear diagnosis of specific characters. -

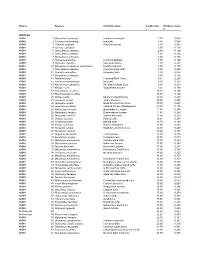

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

Movement, Home Range and Habitat Use in Leopard Tortoises (Stigmochelys Pardalis) on Commercial

Movement, home range and habitat use in leopard tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis) on commercial farmland in the semi-arid Karoo. Martyn Drabik-Hamshare Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Discipline of Ecological Sciences School of Life Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Campus 2016 ii ABSTRACT Given the ever-increasing demand for resources due to an increasing human population, vast ranges of natural areas have undergone land use change, either due to urbanisation or production and exploitation of resources. In the semi-arid Karoo of southern Africa, natural lands have been converted to private commercial farmland, reducing habitat available for wildlife. Furthermore, conversion of land to energy production is increasing, with areas affected by the introduction of wind energy, solar energy, or hydraulic fracturing. Such widespread changes affects a wide range of animal and plant communities. Southern Africa hosts the highest diversity of tortoises (Family: Testudinidae), with up to 18 species present in sub-Saharan Africa, and 13 species within the borders of South Africa alone. Diversity culminates in the Karoo, whereby up to five species occur. Tortoises throughout the world are undergoing a crisis, with at least 80 % of the world’s species listed at ‘Vulnerable’ or above. Given the importance of many tortoise species to their environments and ecosystems— tortoises are important seed dispersers, whilst some species produce burrows used by numerous other taxa—comparatively little is known about certain aspects relating to their ecology: for example spatial ecology, habitat use and activity patterns. -

Growing and Shrinking in the Smallest Tortoise, Homopus Signatus Signatus: the Importance of Rain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Oecologia (2007) 153:479–488 DOI 10.1007/s00442-007-0738-7 GLOBAL CHANGE AND CONSERVATION ECOLOGY Growing and shrinking in the smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus: the importance of rain Victor J. T. Loehr · Margaretha D. Hofmeyr · Brian T. Henen Received: 21 November 2006 / Accepted: 21 March 2007 / Published online: 24 April 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Climate change models predict that the range of dorso-ventrally, so a reduction in internal matter due to the world’s smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus, starvation or dehydration may have caused SH to shrink. will aridify and contract in the next decades. To evaluate Because the length and width of the shell seem more rigid, the eVects of annual variation in rainfall on the growth of reversible bone resorption may have contributed to shrink- H. s. signatus, we recorded annual growth rates of wild age, particularly of the shell width and plastron length. individuals from spring 2000 to spring 2004. Juveniles Based on growth rates for all years, female H. s. signatus grew faster than did adults, and females grew faster than need 11–12 years to mature, approximately twice as long as did males. Growth correlated strongly with the amount of would be expected allometrically for such a small species. rain that fell during the time just before and within the However, if aridiWcation lowers average growth rates to the growth periods. Growth rates were lowest in 2002–2003, level of 2002–2003, females would require 30 years to when almost no rain fell between September 2002 and mature. -

Conservation of South African Tortoises with Emphasis on Their Apicomplexan Haematozoans, As Well As Biological and Metal-Fingerprinting of Captive Individuals

CONSERVATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN TORTOISES WITH EMPHASIS ON THEIR APICOMPLEXAN HAEMATOZOANS, AS WELL AS BIOLOGICAL AND METAL-FINGERPRINTING OF CAPTIVE INDIVIDUALS By Courtney Antonia Cook THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (Ph.D.) in ZOOLOGY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Prof. N. J. Smit Co-supervisors: Prof. A. J. Davies and Prof. V. Wepener June 2012 “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” Henry Beston (1928) ABSTRACT South Africa has the highest biodiversity of tortoises in the world with possibly an equivalent diversity of apicomplexan haematozoans, which to date have not been adequately researched. Prior to this study, five apicomplexans had been recorded infecting southern African tortoises, including two haemogregarines, Haemogregarina fitzsimonsi and Haemogregarina parvula, and three haemoproteids, Haemoproteus testudinalis, Haemoproteus balazuci and Haemoproteus sp.