Studies Spring 2014 OUTSIDE COVER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University Recommended Citation Witkowski, Monica C., ""Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 27. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/27 “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 by Monica C. Witkowski A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University, 2010 What was the legal status of women in early colonial Maryland? This is the central question answered by this dissertation. Women, as exemplified through a series of case studies, understood the law and interacted with the nascent Maryland legal system. Each of the cases in the following chapters is slightly different. Each case examined in this dissertation illustrates how much independent legal agency women in the colony demonstrated. Throughout the seventeenth century, Maryland women appeared before the colony’s Provincial and county courts as witnesses, plaintiffs, defendants, and attorneys in criminal and civil trials. Women further entered their personal cattle marks, claimed land, and sued other colonists. This study asserts that they improved their social standing through these interactions with the courts. By exerting this much legal knowledge, they created an important place for themselves in Maryland society. Historians have begun to question the interpretation that Southern women were restricted to the home as housewives and mothers. -

Sedevacantists and Una Cum Masses

Dedicated to Patrick Henry Omlor The Grain of Incense: Sedevacantists and Una Cum Masses — Rev. Anthony Cekada — www.traditionalmass.org Should we assist at traditional Masses offered “together with Thy servant Benedict, our Pope”? articulate any theological reasons or arguments for “Do not allow your tongue to give utterance to what your heart knows is not true.… To say Amen is to what he does. subscribe to the truth.” He has read or heard the stories of countless early — St. Augustine, on the Canon martyrs who chose horrible deaths, rather than offer even one grain of incense in tribute to the false, ecu- “Our charity is untruthful because it is not severe; menical religion of the Roman emperor. So better to and it is unpersuasive, because it is not truthful… Where there is no hatred of heresy, there is no holi- avoid altogether the Masses of priests who, through ness.” the una cum, offer a grain of incense to the heresiarch — Father Faber, The Precious Blood Ratzinger and his false ecumenical religion… In many parts of the world, however, the only tra- IN OUR LIVES as traditional Catholics, we make many ditional Latin Mass available may be one offered by a judgments that must inevitably produce logical conse- priest (Motu, SSPX or independent) who puts the false quences in our actual religious practice. The earliest pope’s name in the Canon. Faced with choosing this or that I remember making occurred at about age 14. Gui- nothing, a sedevacantist is then sometimes tempted to tar songs at Mass, I concluded, were irreverent. -

Chesapeake Bay and the Restoration Colonies by 1700, the Virginia Colonists Had Made Their Fortunes Primari

9/24: Lecture Notes: Chesapeake Bay and the Restoration Colonies By 1700, the Virginia colonists had made their fortunes primarily through the cultivation of tobacco, setting a pattern that was followed in territories known as Maryland and the Carolinas. Regarding politics and religion: by 1700 Virginia and Maryland, known as the Chesapeake Colonies, differed considerably from the New England colonies. [Official names: Colony and Dominion of Virginia (later the Commonwealth of Virginia) and the Province of Maryland] The Church of England was the established church in Virginia, which meant taxpayers paid for the support of the Church whether or not they were Anglicans. We see a lower degree of Puritan influence in these colonies, but as I have mentioned in class previously, even the term “Puritan” begins to mean something else by 1700. In the Chesapeake, Church membership ultimately mattered little, since a lack of clergymen and few churches kept many Virginians from attending church on a regular basis, or with a level of frequency seen in England. Attending church thus was of somewhat secondary importance in the Virginia colony and throughout the Chesapeake region, at least when compared to the Massachusetts region. Virginia's colonial government structure resembled that of England's county courts, and contrasted with the somewhat theocratic government of Massachusetts Bay and other New England colonies. And again, they are Theocratic – a government based on religion. Now even though they did not attend church as regularly as those living in England, this does not mean that religion did not play a very important role in their lives. -

November 8, 2019 the Honorable Alex Azar Secretary Department of Health and Human Services Washington, DC Dear Secretary Azar: W

November 8, 2019 The Honorable Alex Azar Secretary Department of Health and Human Services Washington, DC Dear Secretary Azar: We write to you as parents, grandparents and educators to support the President's call to "clear the markets" of all flavored e-cigarettes. Safeguarding the health of our nation's children is paramount to us. Children must be protected from becoming addicted to nicotine and the dangers posed by tobacco product. We ask for your leadership in ensuring that all flavored e-cigarettes, including mint and menthol, are removed from the marketplace. The dramatic increase in the number of youth vaping is staggering and we see it in our communities every day. Every high school in the nation is dealing with this epidemic. From 2017 to 2019, there was a 135 percent increase, and now one out of every four high school youth (27.5%) in America use these products. More than 6 out of 10 of these teens use fruit, menthol or mint- flavored e-cigarettes. The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine concluded there is "substantial evidence" that if a youth or young adult uses an e-cigarette, they are at increased risk of using traditional cigarettes. Flavors in tobacco products attract kids. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the candy and fruit flavors found in e-cigarettes are one of the primary reason’s kids use them. A 2015 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 81 percent of youth who have ever used tobacco products initiated with a flavored product. -

Saint Ignatius Asks, "Are You Sure

Saint Ignatius Asks, "Are You Sure You Know Who I Am?" Joseph Veale, S.J. X3701 .S88* ONL PER tudies in the spirituality of Jesuits.. [St. Loui >sue: v.33:no.4(2001:Sept.) jrivalDate: 10/12/2001 Boston College Libraries 33/4 • SEPTEMBER 2001 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. It concerns itself with topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and prac- tice of Jesuits, especially United States Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces through its publication, STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS. This is done in the spirit of Vatican II's recommendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the journal, while meant especially for American Jesuits, is not exclusively for them. Others who may find it helpful are cordially welcome to make use of it. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR William A. Barry, S.J., directs the tertianship program and is a writer at Cam- pion Renewal Center, Weston, MA (1999). Robert L. Bireley, S.J., teaches history at Loyola University, Chicago, IL (2001) James F. Keenan, S.J., teaches moral theology at Weston Jesuit School of Theol- ogy, Cambridge, MA (2000). -

Hannah Wasco | Graduate School of Education and Human Development

Addressing Universities’ Historic Ties to Slavery Hannah Wasco | Graduate School of Education and Human Development Universities’ Historic Ties to Slavery Responding to History Social Justice Approach • Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing movement of Apologies: Should include an acknowledgment of the offense, acceptance of responsibility, expression of A social justice approach– encompassing both distributive and procedural universities in the United States acknowledging and addressing their regret, and a commitment to non-repetition of the offense. While some scholars say the single act of an justice– provides a framework for universities to both authentically historic ties to slavery. apology is enough, others argue that it is necessary to consider an apology as a process with no end point. address their historic ties to slavery and effectively correct present • Historical records irrefutably demonstrate that early American higher ------------------------------------------------- systems of racism and oppression on campus. education institutions permitted, protracted, and profited from the Reparations: Most often understood as money, reparations can also come in the form of land, education, ------------------------------------------------- African slave trade. mental health services, employment opportunities, and the creation of monuments and museums. Distributive Justice: American universities benefited directly and o Slaves constructed buildings, cleaned students’ rooms, and prepared However, discussions of reparations must be aware of the risk of “commodifying” suffering and falling into indirectly from the enslavement of human beings; social justice not only meals; slave labor on adjoining plantations funded endowments and the “one-time payment trap.” calls for the recognition of this historic inequity, but also demands that scholarships; and slaves were sold for profit and to repay debts. -

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(S): Catherine O’Donnell Source: the William and Mary Quarterly, Vol

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(s): Catherine O’Donnell Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 101-126 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.1.0101 Accessed: 17-10-2018 15:23 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly This content downloaded from 134.198.197.121 on Wed, 17 Oct 2018 15:23:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 101 John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Catherine O’Donnell n 1806 Baltimoreans saw ground broken for the first cathedral in the United States. John Carroll, consecrated as the nation’s first Catholic Ibishop in 1790, had commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe and worked with him on the building’s design. They planned a neoclassi- cal brick facade and an interior with the cruciform shape, nave, narthex, and chorus of a European cathedral. -

Volume 24 Supplement

2 GATHERED FRAGMENTS Leo Clement Andrew Arkfeld, S.V.D. Born: Feb. 4, 1912 in Butte, NE (Diocese of Omaha) A Publication of The Catholic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Joined the Society of the Divine Word (S.V.D.): Feb. 2, 1932 Educated: Sacred Heart Preparatory Seminary/College, Girard, Erie County, PA: 1935-1937 Vol. XXIV Supplement Professed vows as a Member of the Society of the Divine Word: Sept. 8, 1938 (first) and Sept. 8, 1942 (final) Ordained a priest of the Society of the Divine Word: Aug. 15, 1943 by Bishop William O’Brien in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary, Techny, IL THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA Appointed Vicar Apostolic of Central New Guinea/Titular Bishop of Bucellus: July 8, 1948 by John C. Bates, Esq. Ordained bishop: Nov. 30, 1948 by Samuel Cardinal Stritch in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary Techny, IL The biographical information for each of the 143 prelates, and 4 others, that were referenced in the main journal Known as “The Flying Bishop of New Guinea” appears both in this separate Supplement to Volume XXIV of Gathered Fragments and on the website of The Cath- Title changed to Vicar Apostolic of Wewak, Papua New Guinea (PNG): May 15, 1952 olic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania — www.catholichistorywpa.org. Attended the Second Vatican Council, Sessions One through Four: 1962-1965 Appointed first Bishop of Wewak, PNG: Nov. 15, 1966 Appointed Archbishop of Madang, PNG, and Apostolic Administrator of Wewak, PNG: Dec. 19, 1975 Installed: March 24, 1976 in Holy Spirit Cathedral, Madang Richard Henry Ackerman, C.S.Sp. -

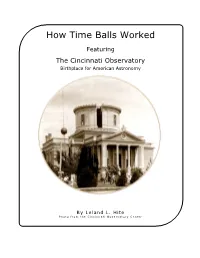

How Time Balls Worked

How Time Balls Worked Featuring The Cincinnati Observatory Birthplace for American Astronomy By Leland L. Hite Photo from the Cincinnati Observatory Center Table of Contents How The Time Ball Worked ……………………………………….……………. 2 The Going Time At The Observatory ………………………………………. 13 Acknowledgments …………………………………………….………..… 16 Photo Gallery ………………………………………………………..………..17 Table 1, Time Balls (Partial Worldwide Listing) …….….... 28 Table 2, Time Guns (Partial Worldwide Listing) ……….... 36 See the video illustrating over 200 worldwide time balls, guns, and flaps: http://youtu.be/mL7hNZCoa7s July 1, 2014 From: LeeHite.org Updated 5/13/2021 ▲ Contents Menu ▲ Page 1 of 36 How Time Balls Worked “Excuse me, do you have the time?” asks a person from downtown. “Sure, it is ten past ten o’clock,” answers the person from Mt. Healthy. “Oh my, I have twenty past ten o’clock.” Immediately, the person from Loveland speaks up to say, “You’re both wrong. The time is twenty-eight past ten o’clock.” Who is correct and how do you know? How was time determined in the Greater Cincinnati area before radio signals, telegraphy, or other electronic methods? Perhaps your answer would include a shadow clock or maybe the pendulum clock. The question is how did a clock registering noon on the west side of Cincinnati Precisely positioned brick, stone, and bronze make this Planispheric coincide with a clock registering noon on the east Analemma Sundial accurate to within side? Many citizens depended on railway time, but 20 seconds and visible to all that visit how did they decide the correct time? As the observatory. Image by L. Hite civilization evolved and industrialization became popular, knowing the correct time both day and night was important. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

In the Footsteps of Saint Philippine Duchesne: a Self-Guided Tour

Saint Philippine Bicentennial 1818-2018 In the footsteps of Saint Philippine Duchesne: A self-guided tour Mother Rose Philippine Duchesne was a pioneer Missouri educator, the first to open a free school west of the Mississippi, the first to open an academic school for girls in the St. Louis, Missouri, area, and the first Catholic sister (along with her four companions) to serve in the St. Louis region. She brought the French-based Society of the Sacred Heart to America. The congregation of sisters was just 18 years old, and she led its daring, first foreign mission. It was energized by her lifelong passion to serve Native Americans. Two hundred years after her arrival in the region, many share the stories of her faith-emboldened tenacity and her passion for girls’ excellent education. Many strive to model her lifelong determination to reflect the love of God always. Canonized on July 3, 1988, she is a patron saint of the Archdiocese of St. Louis. She is known around the world. We hope this guide to seven places where the saint lived and prayed will help you learn more about her often discouraging but remarkable journey of love. Shrine of Saint Philippine Duchesne, St. Charles, Missouri Old St. Ferdinand, A Shrine to Saint Philippine Duchesne, Florissant, Missouri Saint Louis County Locations in Head west downtown St. Louis to Kansas to visit include Mississippi River Mound City and by the Gateway Arch, Centerville Old Cathedral and former (Sugar Creek) City House sites Her footsteps in St. Louis, Missouri Mississippi Riverbank At the southern edge of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, now called the Gateway Arch National Park, drive to the corner of Wharf Street and Chouteau Boulevard, then south on Wharf Street. -

Book Reviews ∵

journal of jesuit studies 4 (2017) 99-183 brill.com/jjs Book Reviews ∵ Thomas Banchoff and José Casanova, eds. The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington, dc: Georgetown University Press, 2016. Pp. viii + 299. Pb, $32.95. This volume of essays is the outcome of a three-year project hosted by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University which involved workshops held in Washington, Oxford, and Florence and cul- minated in a conference held in Rome (December 2014). The central question addressed by the participants was whether or not the Jesuit “way of proceeding […] hold[s] lessons for an increasingly multipolar and interconnected world” (vii). Although no fewer than seven out of the thirteen chapters were authored by Jesuits, the presence amongst them of such distinguished scholars as John O’Malley, M. Antoni Üçerler, Daniel Madigan, David Hollenbach, and Francis Clooney as well as of significant historians of the Society such as Aliocha Mal- davsky, John McGreevy, and Sabina Pavone together with that of the leading sociologist of religion, José Casanova, ensure that the outcome is more than the sum of its parts. Banchoff and Casanova make it clear at the outset: “We aim not to offer a global history of the Jesuits or a linear narrative of globaliza- tion but instead to examine the Jesuits through the prism of globalization and globalization through the prism of the Jesuits” (2). Accordingly, the volume is divided into two, more or less equal sections: “Historical Perspectives” and “Contemporary Challenges.” In his sparklingly incisive account of the first Jesuit encounters with Japan and China, M.