MINIMALIST ART and FRANK STELLA Minimalist Art Is Abstract Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barnett Newman's

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Art and Art History Faculty Research Art and Art History Department 2013 Barnett ewN man's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/art_faculty Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Repository Citation Schreyach, M. (2013). Barnett eN wman's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning. Common Knowledge, 19(2), 351-379. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2073367 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BARNETT NEWMAN’S “SENSE OF SPACE” A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Dorothy Seckler: How would you define your sense of space? Barnett Newman: . Is space where the orifices are in the faces of people talking to each other, or is it not [also] between the glance of their eyes as they respond to each other? Anyone standing in front of my paint- ings must feel the vertical domelike vaults encompass him [in order] to awaken an awareness of his being alive in the sensation of complete space. This is the opposite of creating an environment. This is the only real sensation of space.1 Some of the titles that Barnett Newman gave to his paintings are deceptively sim- ple: Here and Now, Right Here, Not There — Here. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

American Abstract Expressionism

American Abstract Expressionism Cross-Curricular – Art and Social Studies Grades 7–12 Lesson plan and artwork by Edwin Leary, Art Consultant, Florida Description Directions This project deals with the infusion between Art History Teacher preparation: and Art Making through American Abstract Expressionism. Gather examples of artists that dominated this movement, American Abstract Expressionism is truly a U.S. movement that display them in the Art Room with questions of: Who uses emphasizes the act of painting, inherent in the color, texture, organic forms? Dripped and splashed work? Why the highly action, style and the interaction of the artist. It may have been colored work of Kandinsky? Why the figurative aspects of inspired by Hans Hofmann, Arshile Gorky and further developed DeKooning? by the convergence of such artists as Jackson Pollack, William With the students: DeKooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko and Wassily Kandinsky. 1 Discuss the emotions, color and structure of the displayed Objectives artists’ work. Discuss why American Abstract Expressionism is less about • Students can interactively apply an art movement to an art 2 process-painting. style than attitude. • This art-infused activity strengthens their observation and 3 Discuss why these artists have such an attachment of self awareness of a specific artist’s expression. expression as found in their paintings yet not necessarily found in more academic work? Lesson Plan Extensions 4 Gather the materials and explain why the vivid colors of Apply this same concept of investigation, application and art Fluorescent Acrylics were used, and what they do within a making to other movements or schools of art. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and Its Non-Traditional Materials

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2018 Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and its Non-traditional Materials Sandra Hong Sotheby's Institute of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Recommended Citation Hong, Sandra, "Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and its Non-traditional Materials" (2018). MA Theses. 15. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses/15 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. High or Low? The Value of Transitional Paintings by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko Monica Peacock A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Master’s Degree in Art Business Sotheby’s Institute of Art 2018 12,043 Words High or Low? The Value of Transitional Paintings by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko By: Monica Peacock Abstract: Transitional works of art are an anomaly in the field of fine art appraisals. While they represent mature works stylistically and/or contextually, they lack certain technical or compositional elements unique to that artist, complicating the process for identifying comparables. Since minimal research currently exists on the value of these works, this study sought to standardize the process for identifying transitional works across multiple artists’ markets and assess their financial value on a broad scale through an analysis of three artists: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. -

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

Abstraction in 1936: Barr's Diagrams

ALMOST SINCE THE MOMENT OF ITS FOUNDING, in 1929, The Museum of Modern Art has been committed to the idea that abstraction was an inherent and crucial part of the development of modern art. In fact the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, organized by the Museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., made this argument its central thesis. In an attempt to map how abstraction came to be so important in modern art, Barr created a now famous diagram charting the history of Cubism’s and abstraction’s development from the 1890s to the 1930s, from the influence of Japanese prints to the aftermath of Cubism and Constructivism. Barr’s chart, which was published on the dust jacket of the exhibition’s catalogue (plate 452), began in an early version as a simple outline of the key factors affecting early modern art, and of the development of Cubism in particular, but over successive iterations became increasingly complex in its overlapping and intersecting lines of influence ABSTRACTION 1 (plates 453–58). The chart has two principal axes: on the vertical, time, and on the horizontal, styles or movements, with both lead- ing inexorably to the creation of abstract art. Key non-Western IN 1936: influences, such as “Japanese Prints,” “Near-Eastern Art,” and “Negro Sculpture,” are indicated by a red box. “Machine Esthetic” is also highlighted by a red box, and “Modern Architecture,” by 452. The catalogue for Cubism and Abstract Art, an exhibition at the Museum BARR’S which Barr meant the International Style, by a black box. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

Fauvism and Expressionism

Level 3 NCEA Art History Fauvism and Expressionism Workbook Pages Fauvism and Expressionism What this is: Acknowledgements These pages are part of a framework for students studying This workbook was made possible: NCEA Level 3 Art History. It is by no means a definitive • by the suggestions of Art History students at Christchurch document, but a work in progress that is intended to sit Girls’ High School, alongside internet resources and all the other things we • in consultation with Diane Dacre normally do in class. • using the layout and printing skills of Chris Brodrick of Unfortunately, illustrations have had to be taken out in Verve Digital, Christchurch order to ensure that copyright is not infringed. Students could download and print their own images by doing a Google image search. While every attempt has been made to reference sources, many of the resources used in this workbook were assembled How to use it: as teaching notes and their original source has been difficult to All tasks and information are geared to the three external find. Should you become aware of any unacknowledged source, Achievement Standards. I have found that repeated use of the please contact me and I will happily rectify the situation. charts reinforces the skills required for the external standards Sylvia Dixon and gives students confidence in using the language. [email protected] It is up to you how you use what is here. You can print pages off as they are, or use the format idea and the templates to create your own pages. More information: You will find pages on: If you find this useful, you might be interested in the full • the Blaue Reiter workbook. -

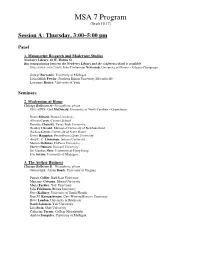

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17)

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17) Session A: Thursday, 3:00–5:00 pm Panel 1. Manuscript Research and Modernist Studies Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St. Bus transportation between the Newberry Library and the conference hotel is available ORGANIZER AND CHAIR: John Timberman Newcomb, University of Illinois – Urbana-Champaign George Bornstein, University of Michigan Laura Milsk Fowler, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Lawrence Rainey, University of York Seminars 2. Modernism at Home Chicago Ballroom A—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Gail McDonald, University of North Carolina – Greensboro Dawn Blizard, Brown University Allison Carey, Cannon School Dorothy Chansky, Texas Tech University Bradley Clissold, Memorial University of Newfoundland Barbara Green, University of Notre Dame Kevin Hagopian, Pennsylvania State University Amy E. C. Linneman, Indiana University Marion McInnes, DePauw University Phoebe Putnam, Harvard University Jin Xiaotian Skye, University of Hong Kong Eve Sorum, University of Michigan 3. The Author Business Chicago Ballroom B—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Alison Booth, University of Virginia Patrick Collier, Ball State University Marianne Cotugno, Miami University Maria Fackler, Yale University Julia Friedman, Brown University Peter Kalliney, University of South Florida Kurt M. Koenigsberger, Case Western Reserve University Bette London, University of Rochester Randi Saloman, Yale University Lisa Stein, Ohio University Catherine Turner, College Misericordia Andrea Zemgulys, University of Michigan 4. Anthropological -

Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms

ABSTRACT ART AND THE CONTESTED GROUND OF AFRICAN MODERNISMS By PATRICK MUMBA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of FINE ART of RHODES UNIVERSITY November 2015 Supervisor: Tanya Poole Co-Supervisor: Prof. Ruth Simbao ABSTRACT This submission for a Masters of Fine Art consists of a thesis titled Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms developed as a document to support the exhibition Time in Between. The exhibition addresses the fact that nothing is permanent in life, and uses abstract paintings that reveal in-between time through an engagement with the processes of ageing and decaying. Life is always a temporary situation, an idea which I develop as Time in Between, the beginning and the ending, the young and the aged, the new and the old. In my painting practice I break down these dichotomies, questioning how abstractions engage with the relative notion of time and how this links to the processes of ageing and decaying in life. I relate this ageing process to the aesthetic process of moving from representational art to semi-abstract art, and to complete abstraction, when the object or material reaches a wholly unrecognisable stage. My practice is concerned not only with the aesthetics of these paintings but also, more importantly, with translating each specific theme into the formal qualities of abstraction. In my thesis I analyse abstraction in relation to ‘African Modernisms’ and critique the notion that African abstraction is not ‘African’ but a mere copy of Western Modernism. In response to this notion, I have used a study of abstraction to interrogate notions of so-called ‘African-ness’ or ‘Zambian-ness’, whilst simultaneously challenging the Western stereotypical view of African modern art.