My Mother Learns English Let Me Introduce You to My Mother, Annie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

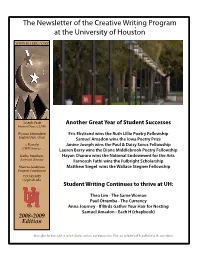

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston WWW.UH.EDU/CWP Joseph Pratt Another Great Year of Student Successes Interim Dean, CLASS Wyman Herendeen Eric Ekstrand wins the Ruth Lillie Poetry Fellowship English Dept. Chair Samuel Amadon wins the Iowa Poetry Prize j. Kastely Janine Joseph wins the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship CWP Director Lauren Berry wins the Diane Middlebrook Poetry Fellowship Kathy Smathers Hayan Charara wins the National Endowment for the Arts Assistant Director Farnoosh Fathi wins the Fulbright Scholarship Shatera Anderson Matthew Siegel wins the Wallace Stegner Fellowship Program Coordinator 713.743.3015 [email protected] Student Writing Continues to thrive at UH: Thea Lim - The Same Woman Paul Otremba - The Currency Anna Journey - If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting Samuel Amadon - Each H (chapbook) 2008-2009 Edition Every effort has been made to include faculty, students, and alumni news. Items not included will be published in the next edition. From the Director... This year marks the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston. It has been a rich 30 years, and I thank you all for your contributions. Last year, I wrote about the necessity and the benefit of fallow periods. As with so many things, there is a rhythm to the writing life and genuine growth sometimes requires periods of rest or inactivity that allow for new ways of seeing and writing to emerge. I have been thinking a lot recently about how one sustains a writing life. This is often an issue that does not get sufficient attention in graduate school. -

LOUDER THAN a BOMB FILM CURRICULUM E Dited B Y a Nna Festa & Gre G Ja C Obs

1 LOUDER THAN A BOMB FILM CURRICULUM CREATED BY KEVIN COVAL EDITED BY ANNA FESTA & GREG JACOBS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The Film The Pedagogy The Curriculum ACTIVITIES 1 HOME Adam Gottlieb Kevin Coval & Carl Sandburg 2 EGO TRIPPIN’ Nate Marshall Nikki Giovanni & Idris Goodwin 3 THE PORTRAIT Nova Venerable William Carlos Williams 4 PERSONA: VOICING AMERICAN ARCHETYPES Lamar Jorden Patricia Smith 5 GROUP PIECE PART #1: THE CHOREOPOEM as COMMUNITY Theater The Steinmenauts 6 GROUP PIECE PART #2: THE CHOREOPOEM as COMMUNITY Theater The Steinmenauts Ntozake Shange GLOSSARY END NOTES CONTACT 2 ABOUT THE FILM DIRECTORS JON SISKEL & GREG JACOBS As is the case with so many documentary subjects, we stumbled on Louder Than a Bomb completely by accident. One late winter weekend, Greg happened to drive by the Metro, a legendary Chicago music venue, and saw a line of kids that stretched down the block. What made the scene unusual wasn’t just the crowd—it was what they were waiting for: the marquee read, “Louder Than a Bomb Youth Poetry Slam Finals.” Teenagers, hundreds of them, of every shape, size, and color, lined up on a Saturday night to see poetry? In Chicago!? Whatever this thing is, it must be interesting. The more we saw, the more convinced we became that, in fact, it was. There was the LTAB community—a remarkable combination of democracy and meritocracy, where everyone’s voice is respected, but the kids all know who can really bring it. There were the performances themselves—bold, brave, and often searingly memorable. And there were the coaches, teachers, and parents, whose tireless support would become a quietly inspiring thread throughout the film. -

Pdf (414.61 K)

مجلة كلية اﻵداب والعلوم اﻹنسانية .… Traumatic Experiences in Selected Traumatic Experiences in Selected Contemporary Poems by Patricia Smith اخلربات الصادمة يف قصائد معاصرة خمتارة للشاعرة باتريشيا مسيث By Sara Ahmed Mohamed الرسالة تبحث اخلربات والتجارب الصادمة يف جمموعة قصائد خمتارة للشاعرة باتريشيا مسيث. الدارسة تتبع رؤية الباحثة جوديث هري من . خﻻل دراستها لنظرية الصدمة، قامت الباحثة جوديث هريمن بوضع إطار حددت من خﻻله املسار الذي يتبعه الشخص الذي تعرض لتجربة صادم ة. تقول هريمن ا نه بعد مرور الشخص بتجربة صادمة فإنه يتعرض جملموعة من اﻷعراض تسمى اضطرابا ت ما بعد الصدمة وهي فرط التيقظ و تداخل ذكريات احلادث مث حالة من اﻹنقباض النفسي. بعد فرتة طويلة و شاقة من معاناة الشخص من هذه العراض، يبدأ الشخص رحلة طويلة للتعايف. خﻻل هذه الفرتة مير الشخص بالعديد من املراحل يقوم أثناءها بإعادة بناء شخصيته اليت مت تشويهها خﻻل مروره بالصدم ة. ﻻ يوجد فرتة حمددة لنهاية اﻷعراض ولكن الفرتة ختتلف من شخص ﻵخر. خﻻل هذه الفرتة مير الشخص بالعديد من الصراعات النفسية واﻷوقات العصيب ة. بعد كل هذا العمل و اجلهد واإلصرار ، يبدأ الشخص يف إعادة النظر ملا مر به وحيتقره . وينظر حلياته اجلديدة وجيدها افضل بكثري من حياته القدمية . مل يعد الشخص املصدوم اآلن يهتم بذكرى التجربة الصادمة بل أصبح جيدها مملة .عندما يصل الشخص هلذه املرحلة يكون قد وصل لنقطة احنالل الصدمة. هذه املرحلة يف شعر مسيث مرت بالعديد من التضحيات و اأﻻمل واإلصرار أمهها عالقتها عالقتها بأمها واليت نتج عنها تضحيتها وحتجيمها هلذه العالق ة . من خالل هذه الدراسة يتضح جليا مرور باتريشيا مسيث بالعديد من اخلربات الصادمة وذلك ألسباب عنصرية واخرى عائلية . هذه اخلربات إنعكست على شعرها حيث اتسمت قصائدها بالواقعية والتعبري عن الواقع الصادم الذي متر به مسيث مع غريها ممن يعانون جتارب مماثلة. -

LIBRARY of CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 Poetry Nation

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 poetry nation INSIDE Rosa Parks and the Struggle for Justice A Powerful Poem of Racial Violence PLUS Walt Whitman’s Words American Women Poets How to Read a Poem WWW.LOC.GOV In This Issue MARCH/APRIL 2015 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE FEATURES Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 4 No. 2: March/April 2015 Mission of the Library of Congress The Power of a Poem 8 Billie Holiday’s powerful ballad about racial violence, “Strange Fruit,” The mission of the Library is to support the was written by a poet whose works are preserved at the Library. Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people. National Poets 10 For nearly 80 years the Library has called on prominent poets to help Library of Congress Magazine is issued promote poetry. bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and Beyond the Bus 16 The Rosa Parks Collection at the Library sheds new light on the research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in remarkable life of the renowned civil rights activist. 6 the United States. Research institutions and Walt Whitman educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at www.loc.gov/lcm. -

Untitled, Reveals a Characteristic Ritual Language That Would Accompany the Religious Rite of Burning Certain Plants in Order to Produce “The Smoke of Life” (L

1 2 3 4 Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 9 PART I: BACK TO THE ROOTS ............................................................. 13 Oral Art and Literature .............................................................................. 13 Orality and Literacy .................................................................................. 16 Medial and Conceptional Orality ....................................................... 16 Medial and Conceptional Literacy ..................................................... 18 Primary Orality and Oral Poetry................................................................ 22 Native American Oral Poems........................................................... 23 Secondary Orality and New Oral Poems................................................... 28 “Words from the Edge”..................................................................... 31 PART II: LISTEN UP!................................................................................ 39 The Performing Voices of Poetry.............................................................. 39 Narrative Poetry ................................................................................. 40 Dramatic Poetry ................................................................................. 43 Lyric Poetry ....................................................................................... -

Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Fall 2019 A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry Anthony Blacksher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Poetry Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Television Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blacksher, Anthony. (2019). A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 148. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/148. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/148 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry By Anthony Blacksher Claremont Graduate University 2019 i Copyright Anthony Blacksher, 2019 All rights reserved ii Approval of the Dissertation Committee This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Anthony Blacksher as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of doctorate of philosophy in Cultural Studies with a certificate in Africana Studies. -

Representing Race: Re/Framing Black Lives and Restoring Grievability

Representing Race: Re/framing Black Lives and Restoring Grievability by Victoria Kiely A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Victoria Kiely, January, 2021 ABSTRACT REPRESENTING RACE: RE/FRAMING BLACK LIVES AND RESTORING GRIEVABILITY Victoria Kiely Advisor: University of Guelph, 2021 Dr. Jade Ferguson This thesis examines four highly publicized instances of anti-Black violence alongside a corresponding artistic or literary representation of the victim. Chapter one studies the photographic documentation of Emmett Till’s lynching from 1955 before turning to Dana Schutz’s painting “Open Casket” (2016). Chapter two considers the videotaped beating of Rodney King from 1991 and Anna Deavere Smith’s theatrical piece Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 (1993). Chapter three contextualizes the Black Lives Matter movement and analyzes the impact of Trayvon Martin’s and Michael Brown’s deaths through Patricia Smith’s poetry collection Incendiary Art (2017). Throughout these three chapters, I argue that Black lives are hegemonically framed as ungrievable and disposable through the circulation of anti-Black rhetoric and imagery. However, the hegemony of anti-Blackness can be resisted through artistic and literary re-presentations that frame their subjects as worthy of “protecting, sheltering, living, mourning,” ultimately asserting the value of Black life (Butler 53). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to express my sincere gratitude to those who have supported me throughout my program and while writing my thesis. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Jade Ferguson who went above and beyond to lead me through this process with patience, compassion, and empathy. -

"Creativity in Times of Crisis"

Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania Presents "ShippensburgCreativi tUniversityy in T ofi mPennsylvaniaes of C presentsrisis" Featuring award-winning poet Patricia Smith “CreativityOctob einr 4 tTimesh - 6th, 2 of018 Crisis” featuring Award-Winning Author and Poet Patricia Smith October 4-6, 2018 Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania Presents "Creativity in Times of Crisis" Featuring award-winning poet Patricia Smith October 4th - 6th, 2018 Shippensburg University’s Department of English welcomes EAPSU English Association of Pennsylvania State Universities and Award-Winning Author and Poet Patricia Smith October 4-6, 2018 About Patricia Smith Patricia Smith is the award-winning author of eight critically-acclaimed books of poetry, including Incendiary Art (Triquarterly Books, 2017), winner of the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the 2018 NAACP Image Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, as well as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah (Coffee House Press, 2012), winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Blood Daz- zler (Coffee House Press, 2008), a National Book Award finalist; and Gotta Go, Gotta Flow (CityFiles Press, 2015), a collaboration with award-winning Chicago photographer Michael Abramson. Her other books include the poetry volumes Teahouse of the Almighty (Coffee House Press, 2006), Close to Death(Zoland Books, 1998), Big Towns Big Talk (Zoland Books, 2002), Life According to Motown (Tia Chucha, 1991); the children’s book Janna and the Kings (Lee & Low, 2013), and the history Af- ricans in America (Mariner, 1999), a companion book to the award-winning PBS series. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Paris Review, The Baffler, The Wash- ington Post, The New York Times, Tin Houseand in Best American Poetry, Best American Essays and Best American Mystery Stories. -

An African American Poetry Reader: Renaissance and Resistance

An African American Poetry Reader: Renaissance and Resistance Inside this packet is an abbreviated and non-chronological tour of over three centuries of African American poetry. Read through the packet and choose at least three poems by different poets that interest you to spend time with and prepare for discussion. While re-reading your chosen poems, consider the following questions as they apply: *What kind of relationship does race play with other identities, such as other non-white and white racial identities, as well as with gender, sexual orientation, and class? *What kind of relationship do the poets imagine with you, the reader? *How would you describe the familial and romantic relationships that are depicted in these poems? *What kind of work do these poets depict? What is important to you about the ways they portray this labor? *How do the poets interact with and re-imagine American history? *How do these poets see themselves in relation to world events, cultural institutions, or to other transnational struggles? *How do the poets interact with other forms of art and other artists? How do they play with poetic form? *How do the poets interact with or re-imagine the natural world? *What role does memory play in these poems? *How do these poets respond to violence? What kinds of violence appear in these poems? *Do any of your poems contradict or seem to respond to other poems in this collection? *How do these poets create or insist on joy? Compiled by Paisley Rekdal, University of Utah, 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. -

Via Issuelab

BLUEPRINTS BLUE PRINTS The University of Utah Press •Salt Lake City The Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute, Poetry Foundation •Chicago BLUE PRINTS Bringing Poetry into Communities Edited by KATHARINE COLES Copyright © 2011 by The Poetry Foundation. All rights reserved. Blueprints is a copublication of the Poetry Foundation and the University of Utah Press. “One Heart at a Time: The Creation of Poetry Out Loud” © 2011 by Dana Gioia and The Poetry Foundation. All rights reserved. Excerpts from Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brook- lyn, and Other Identities copyright © 1993, 1997 by Anna Deveare Smith and Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 copyright © 2003 by Anna Deveare Smith. Reprinted courtesy of the author. This material may not be published, performed, or used in any way without the written permission of the author. The Defiance House Man colophon is a registered trademark of the University of Utah Press. It is based upon a four-foot-tall, Ancient Puebloan pictograph (late PIII) near Glen Canyon, Utah. 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blueprints : bringing poetry to communities / edited by Katharine Coles. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-60781-147-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Poetry—Programmed instruction. 2. Poetry—Social aspects. 3. Poetry—tudy and teaching. I. Coles, Katharine. PN1031.B57 2011 808.1—dc22 2011002347 CONTENTS vii AckNOWLEDGMENTS ix INTRODUCTION Katharine Coles SECTION I ALIVE IN THE WOR(L)D: WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO 3 THE FLYWHEEL: On the Relationship between Poetry