Via Issuelab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston

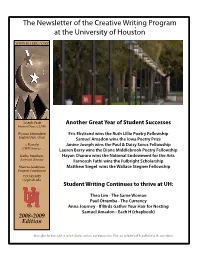

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston WWW.UH.EDU/CWP Joseph Pratt Another Great Year of Student Successes Interim Dean, CLASS Wyman Herendeen Eric Ekstrand wins the Ruth Lillie Poetry Fellowship English Dept. Chair Samuel Amadon wins the Iowa Poetry Prize j. Kastely Janine Joseph wins the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship CWP Director Lauren Berry wins the Diane Middlebrook Poetry Fellowship Kathy Smathers Hayan Charara wins the National Endowment for the Arts Assistant Director Farnoosh Fathi wins the Fulbright Scholarship Shatera Anderson Matthew Siegel wins the Wallace Stegner Fellowship Program Coordinator 713.743.3015 [email protected] Student Writing Continues to thrive at UH: Thea Lim - The Same Woman Paul Otremba - The Currency Anna Journey - If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting Samuel Amadon - Each H (chapbook) 2008-2009 Edition Every effort has been made to include faculty, students, and alumni news. Items not included will be published in the next edition. From the Director... This year marks the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston. It has been a rich 30 years, and I thank you all for your contributions. Last year, I wrote about the necessity and the benefit of fallow periods. As with so many things, there is a rhythm to the writing life and genuine growth sometimes requires periods of rest or inactivity that allow for new ways of seeing and writing to emerge. I have been thinking a lot recently about how one sustains a writing life. This is often an issue that does not get sufficient attention in graduate school. -

A Tradition of Excellence Continues

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston WWW.UH.EDU/CWP A Tradition of Excellence Continues: John Antel Dean, CLASS Wyman Herendeen English Dept. Chair j. Kastely CWP Director Kathy Smathers Assistant Director Shatera Dixon Program Coordinator 713.743.3015 [email protected] This year we welcome two new and one visiting faculty member—all are exciting writers; all are compelling teachers. 2006-2007 Edition Every effort has been made to include faculty, students, and alumni news. Items not included will be published in the next edition. As we begin another academic year, I am struck by how much change the Program has endured in the past year. After the departure of several faculty members the previous year, we have hired Alexander Parsons and Mat John- son as new faculty members in fiction into tenure track positions, and we also hired Liz Waldner as a visitor in poetry for the year. Our colleague, Daniel Stern, passed away this Spring, and he will be missed. Adam Zagajew- ski will take a visiting position in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago this year, and that Committee will most likely become his new academic home. Ed Hirsh submitted his letter of resignation this Spring, and although Ed had been in New York at the Guggenheim for the last five years, he had still officially been a member of the Creative Writing Program on leave. And Antonya Nelson returned from leave this Spring to continue her teaching at UH. So there has been much change. -

November 2012

founded in 1912 by harriet monroe November 2012 FOUNDED IN 1912 BY HARRIET MONROE volume cci • number 2 CONTENTS November 2012 POEMS elizabeth spires 95 Pome hailey leithauser 96 Mockingbird vijay seshadri 98 Sequence casey thayer 102 The Hurt Sonnet idra novey 103 The Visitor La Prima Victoria Of the Divine as Absence and Single Letter donald revell 106 Borodin katie ford 107 The Soul Foreign Song Speak to Us jim harrison 110 The Present The Girls of Winter joanna klink 112 Toward what island-home am I moving david yezzi 113 Cough lisa williams 114 Torch POET photos the editors 117 Photographs Notes RUTH Lilly poetry FELLOWS reginald dwayne betts 149 At the End of Life, a Secret For the City that Nearly Broke Me A Postmodern Two-Step nicholas friedman 154 The Magic Trick As Is Not the Song, but After richie hofmann 157 Fresco Imperial City Keys to the City jacob saenz 160 I Remember Lotería GTA: San Andreas (or, “Grove Street, bitch!”) Blue Line Incident rickey laurentiis 166 Southern Gothic Swing Low You Are Not Christ COMMENT clive james 171 A Stretch of Verse adam kirsch 182 Rocket and Lightship letters 193 contributors 195 announcement of prizes 197 back page 207 Editor christian wiman Senior Editor don share Associate Editor fred sasaki Managing Editor valerie jean johnson Editorial Assistant lindsay garbutt Reader christina pugh Art Direction winterhouse studio cover art by alex nabaum “Pegged,” 2012 POETRYMAGAZINE.ORG a publication of the POETRY FOUNDATION printed by cadmus professional communications, us Poetry • November 2012 • Volume 201 • Number 2 Poetry (issn: 0032-2032) is published monthly, except bimonthly July / August, by the Poetry Foundation. -

My Mother Learns English Let Me Introduce You to My Mother, Annie

Keepers of the Second Throat “Keepers of the Second Throat” was originally delivered as the keynote address at the Urban Sites Network Conference of the National Writing Project, Portland, Ore., April 2010. n BY PATRICIA SMITH Let me introduce you to my mother, Annie who has dedicated eight hours a week to straightening Pearl Smith of Aliceville, Ala. In the 1950s, along afflicted black tongues. She guides my mother with thousands of other apprehensive but de- patiently through lazy ings and ers, slowly scraping her throat clean of the moist and raging infection termined Southerners, their eyes locked on the of Aliceville, Alabama. There are muttered apologies for second incarnation of the North Star, she packed colored sounds. There is much beginning again. up her whole life and headed for the city, with its I want to talk right before I die. tenements, its promise, its rows of factories like Want to stop saying ‘ain’t’ and ‘I done been’ open mouths feeding on hope. like I ain’t got no sense. I’m a grown woman. I done lived too long to be stupid, One day not too long ago, I called my mother, acting like I just got off the boat. but she was too busy to talk to me. She seemed in My mother a great hurry. When I asked her where she was go- has never been ing, she said, “I’m on my way to my English lesson.” on a boat. But 50 years ago, merely a million of her, clutching strapped cases, Jet’s Emmett Till issue, My Mother Learns English and thick-peppered chicken wings in waxed bags, stepped off hot rumbling buses at Northern depots I. -

Hispanic American Literature, Small, Independent Presses That Rely Upon U.S

HISPANICHISPANIC AMERICANAMERICAN LITELITERRAATURE:TURE: DIVEDIVERRGENCEGENCE && C0MMONALITYC0MMONALITY BY VIRGIL SUAREZ n an autobiographical sketch written in 1986, the some of the best work is coming from such sources. respected Chicano American novelist Rudolfo Increasingly, though, with the recognition associated Anaya observed that “if I am to be a writer, it is with the nation’s most prestigious literary awards -- the ancestral voices of…[my]… people who will the Before Columbus Foundation Award, the National form a part of my quest, my search.” Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize -- Hispanic IAncestral voices are very much a part of Hispanic American authors are being courted by the publishing American literature today, a tradition harking back establishment. more than three centuries that has witnessed a Much of the attention of recent times, justifiably, is dramatic renascence in the past generation. As the owed to the groundbreaking work of the Chicano Arts Hispanic experience in the United States continues to movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the confront issues of identity, assimilation, cultural emergence of Hispanic American poets such as heritage and artistic expression, the works of Rodolfo Gonzales and Luis Alberto Urista (“Alurista,”) Hispanic American writers are read with a great deal and other writers who chronicled the social and of interest and passion. political history of the movement. The campaign was In a sense, the literature functions as a mirror, a propelled by grassroots activists such as Cesar reflection of the way Hispanic Americans are viewed Chavez and Dolores Huerta who played key roles in by the mainstream culture -- but not always the the unionization of migrant workers achieved through majority. -

Poetry Off the Shelf Seamus Heaney Ongoing & Recurring Programs TRANSLATING

OCT 12 poetry off the shelf Seamus Heaney Ongoing & Recurring Programs TRANSLATING . 1 g POETR Y: READINGS & 7 r e L 1 I g O 6 , a t . t i D EVENTS CALENDAR o f o s CONVERSATIONS I g o o N a r A t P Friday, October 12, 7 pm c P i i - VISI T P h S m n r C U Poetry Foundation o e N FAL L THE POETR Y poetry off the shelf P SEPT 13 SONIA S ANCHEZ open house chicago FO UNDA TION Thursday, September 13, 7 pm 13, Saturday, October 13, 9 am – 5 pm 201 2 Poetry Foundation Sunday, October 14, 9 am – 5 pm An e vent seas on LIB RARY. 14, Poetry Foundation The Midwest’s only library dedicated exclusively to poetry, harriet reading series 10 0 years the Poetry Foundation Library exists to promote the reading 14 JOANNE K YGER poetry day EVENTS of poetry in the general public, and to support the editorial Friday, September 14, 6:30 pm 18 SEAMUS HEANEY in t he maki ng… needs of all Poetry Foundation programs and staff. Visitors Poetry Foundation Thursday, October 18, 6 pm POETRYFOUNDATION.ORG ON to the library may browse a collection of 30,000 volumes, Rubloff Auditorium …[A]s a modest attempt to change conditions PO ETRY experience audio and video recordings in private listening poetry off the shelf Art Institute of Chicago absolutely destructive to the most necessary and booths, and view exhibits of poetry-related materials. FO UN DAT ION ( 20 LUCILLE CLIFTON universal of the arts, it is proposed to publish a small 31 2) 787 -7070 poetry off the shelf THE NEW LIBRARY HOURS: TRIBUTE & monthly magazine of verse, which shall give the poets Monday – Friday, 11 am –4pm 22 POETRY & PIANO a chance to be heard, as our exhibitions give artists BOOK LAUNCH Monday, October 22, 7 pm Unless otherwise indicated, Poetry Foundation a chance to be seen… HORIZON Poemtime Thursday, September 20, 7 pm Curtiss Hall events are free on a first come, first served basis. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

LOUDER THAN a BOMB FILM CURRICULUM E Dited B Y a Nna Festa & Gre G Ja C Obs

1 LOUDER THAN A BOMB FILM CURRICULUM CREATED BY KEVIN COVAL EDITED BY ANNA FESTA & GREG JACOBS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The Film The Pedagogy The Curriculum ACTIVITIES 1 HOME Adam Gottlieb Kevin Coval & Carl Sandburg 2 EGO TRIPPIN’ Nate Marshall Nikki Giovanni & Idris Goodwin 3 THE PORTRAIT Nova Venerable William Carlos Williams 4 PERSONA: VOICING AMERICAN ARCHETYPES Lamar Jorden Patricia Smith 5 GROUP PIECE PART #1: THE CHOREOPOEM as COMMUNITY Theater The Steinmenauts 6 GROUP PIECE PART #2: THE CHOREOPOEM as COMMUNITY Theater The Steinmenauts Ntozake Shange GLOSSARY END NOTES CONTACT 2 ABOUT THE FILM DIRECTORS JON SISKEL & GREG JACOBS As is the case with so many documentary subjects, we stumbled on Louder Than a Bomb completely by accident. One late winter weekend, Greg happened to drive by the Metro, a legendary Chicago music venue, and saw a line of kids that stretched down the block. What made the scene unusual wasn’t just the crowd—it was what they were waiting for: the marquee read, “Louder Than a Bomb Youth Poetry Slam Finals.” Teenagers, hundreds of them, of every shape, size, and color, lined up on a Saturday night to see poetry? In Chicago!? Whatever this thing is, it must be interesting. The more we saw, the more convinced we became that, in fact, it was. There was the LTAB community—a remarkable combination of democracy and meritocracy, where everyone’s voice is respected, but the kids all know who can really bring it. There were the performances themselves—bold, brave, and often searingly memorable. And there were the coaches, teachers, and parents, whose tireless support would become a quietly inspiring thread throughout the film. -

A Contextual Interpretation of This Bridge Called My Back: Nationalism, Androcentrism and the Means of Cultural Representation

Camino Real 10: 13. (2018): 27-45 A Contextual Interpretation of This Bridge Called My Back: Nationalism, Androcentrism and the Means of Cultural Representation tErEza Jiroutová KyNčlová Abstract Gloria Anzaldúa’s and Cherríe Moraga’s important contribution to women of color feminism, the anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) and Anzaldúa’s masterpiece Borderlands/La Frontera – The New Mestiza (1987) represented a significant milestone for the evolution of contemporary Chicana literature. This essay proposes to contextualize Gloria Anzaldúa’s and Cherríe Moraga’s revolutionary approach and expose its theoretical and activist depth that has impacted both Chicana writing and –more broadly– contemporary feminist thought. Keywords: Chicana feminism, women of color feminism, androcentrism Resumen La contribución fundamental de Gloria Anzaldúa y Cherríe Moraga al feminismo de las mujeres color, la antología Esta Puente Mi Espalda: Escritos de Mujeres Tereza Jiroutová Kynčlová, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Gender Studies, Charles University, Czech Republic. Her research focuses on contemporary U.S. women writers, feminist literary theory, and postcolonial/decolonial studies. Jiroutová Kynčlová, T. “A Contextual Interpretation of This Bridge Called My Back: Nationalism, Androcentrism and the Means of Cultural Representation”. Camino Real, 10:13. Alcalá de Henares: Instituto Franklin-UAH, 2018. Print. Recibido: 22 de enero de 2018; 2ª versión: 22 de enero de 2018. 27 Camino Real Radicales de Color (1981) y la obra maestra de Anzaldúa Borderlands / La Frontera – The New Mestiza (1987) representaron un hito significativo para la evolución de literatura chicana. Este ensayo propone contextualizar el enfoque revolucionario de Gloria Anzaldúa y Cherríe Moraga y exponer su profundidad teórica y activista la cual ha impactado tanto en la escritura chicana como, más ampliamente, en el pensamiento feminista contemporáneo. -

Angela Jackson

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. ANGELA JACKSON A renowned Chicago poet, novelist, play- wright, and biographer, Angela Jackson published her first book while still a stu- dent at Northwestern University. Though Jackson has achieved acclaim in multi- ple genres, and plans in the near future to add short stories and memoir to her oeuvre, she first and foremost considers herself a poet. The Poetry Foundation website notes that “Jackson’s free verse poems weave myth and life experience, conversation, and invocation.” She is also renown for her passionate and skilled Photo by Toya Werner-Martin public poetry readings. Born on July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, Jackson moved with her fam- ily to Chicago’s South Side at the age of one. Jackson’s father, George Jackson, Sr., and mother, Angeline Robinson, raised nine children, of which Angela was the middle child. Jackson did her primary education at St. Anne’s Catholic School and her high school work at Loretto Academy, where she earned a pre-medicine scholar- ship to Northwestern University. Jackson switched majors and graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Northwestern University in 1977. She later earned her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean studies from the University of Chicago, and, more recently, received an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Bennington College. While at Northwestern, Jackson joined the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she matured under the guidance of legendary literary figures such as Hoyt W Fuller. -

ED371765.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 371 765 IR 055 099 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo; Johnson, Lory TITLE Native American, African American, Asian American and Hispanic American Literature for Preschool through Adult. Hispanic American Literature. Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE Jan 94 NOTE 32p.; For related documents, see IR 055 096-098. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Authors; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; *Hispanic Arerican Literature; *Hispanic Americans; Minority Groups; Nonfiction; Picture Books; Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Iowa ABSTRACT This bibliography acknowledges the efforts of authors in the Hispanic American population. It covers literature by authors of Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Rican descent who are or were U.S. citizens or long-term residents. It is made up of fiction and non-fiction books drawn from standard reviewing documents and other sources including online sources. Its purpose is to give users an idea of the kinds of materials available from Hispanic American authors. It is not meant to represent all titles or all formats which relate to the literature by authors of Hispanic American heritage writing in the United States. Presence of a title in the bibliography does not imply a recommendation by the Iowa Department of Education. The non-fiction materials are in the order they might appear in a library based on the Dewey Decimal Classification systems; the fiction follows. Each entry gives author if pertinent, title, publisher if known, and annotation. Other information includes designations for fiction or easy books; interest level; whether the book is in print; and designation of heritage of author. -

Pdf (414.61 K)

مجلة كلية اﻵداب والعلوم اﻹنسانية .… Traumatic Experiences in Selected Traumatic Experiences in Selected Contemporary Poems by Patricia Smith اخلربات الصادمة يف قصائد معاصرة خمتارة للشاعرة باتريشيا مسيث By Sara Ahmed Mohamed الرسالة تبحث اخلربات والتجارب الصادمة يف جمموعة قصائد خمتارة للشاعرة باتريشيا مسيث. الدارسة تتبع رؤية الباحثة جوديث هري من . خﻻل دراستها لنظرية الصدمة، قامت الباحثة جوديث هريمن بوضع إطار حددت من خﻻله املسار الذي يتبعه الشخص الذي تعرض لتجربة صادم ة. تقول هريمن ا نه بعد مرور الشخص بتجربة صادمة فإنه يتعرض جملموعة من اﻷعراض تسمى اضطرابا ت ما بعد الصدمة وهي فرط التيقظ و تداخل ذكريات احلادث مث حالة من اﻹنقباض النفسي. بعد فرتة طويلة و شاقة من معاناة الشخص من هذه العراض، يبدأ الشخص رحلة طويلة للتعايف. خﻻل هذه الفرتة مير الشخص بالعديد من املراحل يقوم أثناءها بإعادة بناء شخصيته اليت مت تشويهها خﻻل مروره بالصدم ة. ﻻ يوجد فرتة حمددة لنهاية اﻷعراض ولكن الفرتة ختتلف من شخص ﻵخر. خﻻل هذه الفرتة مير الشخص بالعديد من الصراعات النفسية واﻷوقات العصيب ة. بعد كل هذا العمل و اجلهد واإلصرار ، يبدأ الشخص يف إعادة النظر ملا مر به وحيتقره . وينظر حلياته اجلديدة وجيدها افضل بكثري من حياته القدمية . مل يعد الشخص املصدوم اآلن يهتم بذكرى التجربة الصادمة بل أصبح جيدها مملة .عندما يصل الشخص هلذه املرحلة يكون قد وصل لنقطة احنالل الصدمة. هذه املرحلة يف شعر مسيث مرت بالعديد من التضحيات و اأﻻمل واإلصرار أمهها عالقتها عالقتها بأمها واليت نتج عنها تضحيتها وحتجيمها هلذه العالق ة . من خالل هذه الدراسة يتضح جليا مرور باتريشيا مسيث بالعديد من اخلربات الصادمة وذلك ألسباب عنصرية واخرى عائلية . هذه اخلربات إنعكست على شعرها حيث اتسمت قصائدها بالواقعية والتعبري عن الواقع الصادم الذي متر به مسيث مع غريها ممن يعانون جتارب مماثلة.